In 2020, more than 400 companies began trading for the first time after completing a tedious initial public offering (IPO) process. However, many others such as QuantumScape (QS), an electric car battery manufacturer, and DraftKings (DKNG), a daily fantasy sports betting behemoth, did so without an IPO of their own. Instead, they took advantage of a recent trend in financial markets called special purpose acquisition companies (SPAC).

The process of going public is historically time-consuming and takes anywhere from six to 24 months. This process will typically require an investment bank to underwrite a company’s new shares of stock, and the company and the bank will then travel the country hosting roadshows to market the new stock to investors. Depending on the deal size and structure, the bank generally charges between 3.5% to 7% of a company’s gross IPO proceeds for their services performed throughout the process.

However, regulatory slowdowns brought on by COVID-19 made company executives pursuing a traditional IPO anxious that virtual roadshows would become increasingly less effective in drumming up investor interest in new stock issuances, thus opening the door for SPACs.

SPACs are business entities that have no products, employees or revenues to report. Rather, they operate as a temporary shell company with the intention of holding their own IPO to raise “capital,” or money. The money raised from investors in the IPO is then typically used in tandem with an equity investment from a sponsor in order to acquire a target company within a two-year window. This process inadvertently pulls the acquired target business into public markets and allows retail investors to trade their shares freely through the SPAC.

Put simply, a shell company raises money for its own IPO, then uses that money to buy another legitimate company, thereby bringing the acquired legitimate company into the public market.

The approach also gains from being more inclusive.

“We call this poor man’s private equity,” Hui Sono, a professor from JMU’s College of Business, said. “We don’t have millions of dollars to invest in private equity. [SPACs] gives us opportunity, but this opportunity comes with costs. If it’s unregulated, we’re probably taken advantage of.”

SPAC Performance

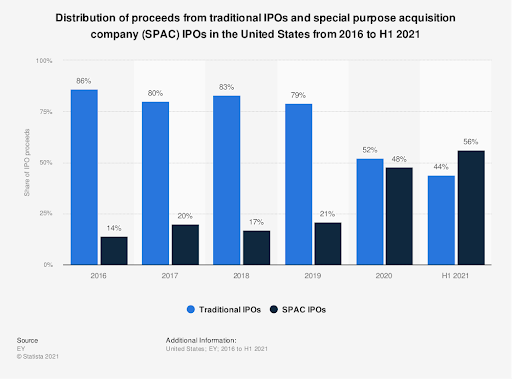

SPACs have been growing significantly in popularity over the last five years. Of the 407 IPOs that took place in 2020, 248 were SPAC offerings. These SPACs took home approximately 48% of all the proceeds raised from IPOs, up more than twice the percentage from the year before. This trend was set to continue well into 2021.

According to Sono, understanding SPAC’s sudden popularity requires further research. While assumptions exist around the impact of COVID-19, she has her own theory:

“Institutional investors — hedge funds, private equity — have all this money but nowhere to invest,” Sono said. “They’re trying to make a profit from the SPACs.”

SPACs high-profile sponsors also add to the dramatic increase. The sponsors of SPACs generally include the company’s management team and occasionally celebrities or other public figures whose name may catch the eyes of potential investors. Typically, the sponsors receive approximately 20% of the equity — a claim to ownership of the business and some of its proceeds — in an SPAC in return for an investment of 3% to 4% of the total IPO proceeds.

Many current and former professional athletes, such as basketball players Shaquille O’Neal and Steph Curry, baseball player Alex Rodriguez and tennis player Serena Williams, have all participated in SPAC ventures. Figures in the sports world in particular have demonstrated interest in SPACs, largely due to the rapid growth of related industries, such as online sports betting and analytics.

Many SPACs with athletes or other public figures involved in the team of sponsors have proven to be hits among investors. As a consequence, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), the government agency tasked with regulating financial markets, has taken notice.

“Celebrity involvement in a SPAC does not mean that the investment in a particular SPAC or SPACs generally is appropriate for all investors,” according to an SEC statement that was released in March. “Celebrities, like anyone else, can be lured into participating in a risky investment or may be better able to sustain the risk of loss.”

Despite their spike in popularity, SPACs have existed since the early ’90s. Although they’ve distanced themselves from their old reputation as unregulated and highly risky, analysts and portfolio managers continue to debate as to what degree they should be included in a retail investor’s portfolio, or if they should be included at all.

Issues with SPACs

SPACs typically have a two-year window from the time of their IPO to identify and complete a merger. Funds raised from investors in the IPO are held in a trust while the SPAC management team negotiates with potential acquisition targets.

However, in the case that a target company cannot be identified, the SPAC’s management has two options: They can either choose to ask their investors for an extension or liquidate the SPAC and give investors their initial investment back.

One of the most significant problems that stems from this time constraint is a misalignment of sponsor and investor interests. Certified financial analyst Duncan Lamont, the head of research and analytics at Schroders, a British multinational asset management firm, published an editorial looking into this exact problem.

“Sponsors are incentivized to get a deal done. Any deal. Even one that is bad for investors could make them a lot of money, and would be preferable to liquidating the SPAC,” according to Lamont’s publication.

This may be why more than 90% of recent SPACs have successfully completed mergers, according to a McKinsey & Company report. Such issues are important considerations for investors who may be evaluating SPAC management prior to making an investment.

Some asset and portfolio managers believe issues like these are fundamental among all SPACs and should be enough to turn retail investors away from investing in them altogether.

Jeremy Grantham, the co-founder and chief investment strategist of Grantham, Mayo, Van Otterloo, a Boston-based asset management firm with $62 billion in assets under management, said in December 2020 that SPACs should be illegal. His critiques included that SPACs continue to escape regulatory oversight and encourage the “most obscene type of investing.” He expressed contempt for the idea that a sound investment decision can be made by giving a sponsor money with the hopes that they’ll then do something useful.

Grantham compared the performance of top SPACs to the tech bubble of the late 1990s, and although some key differences exist, exorbitant SPAC returns have led many to consider the possibility of a mispricing. Each of the top nine performing SPACs in 2020 that had completed a merger returned more than 100% to their investors, with some even achieving returns in the thousands of percentage points at their peak.

Despite being vocally anti-SPAC, Grantham holds more than 10% of his company’s assets in QuantumScape (QS), which went public via a SPAC and has since returned more than 20 times his initial investment.

A Reuters study found that approximately 90% of SPACs that announced acquisitions in 2021 are lagging behind the S&P 500 — a broad market index that tracks the performance of the largest 500 companies listed in the U.S. — based on when they began trading. Moreover, the median performance of a SPAC on the day it announces its merger partner is a decline of 6%.

A paper published by the Yale Journal on Regulation in tandem with professors from Stanford, New York University and the European Corporate Governance Institute also found that investors may be holding up an unsustainable model. The paper, “A Sober Look at SPACs,” found that “although SPACs issue shares for roughly $10 and value their shares at $10 when they merge, by the time of the merger the median SPAC holds cash of just $6.67 per share.”

Causes for this shortage of liquid assets held by the SPAC are largely consequences of costs embedded in SPAC structure. These generally include paying fees associated with the merger and share dilution resulting from sponsor ownership that is disproportionate to the amount of cash contributed.

The same study also found that SPAC investors who hold shares at the time of a merger experience a decline in post-merger share prices of one-third or more.

The final conclusion of this research was that the primary source of poor SPAC performance is share dilution, which is built into SPAC’s corporate structure. SPACs offer warrants — the right to purchase additional shares at a premium — and other options to parties which don’t contribute cash to complete the merger. This ends up decreasing the value of investor’s shares as their overall equity ownership percentage falls as these rights are exercised.

As a result, some SPACs are working to make their shares more attractive to retail investors by reducing the rights offered to sponsors in an effort to decrease this type of share dilution.

The Regulatory Future of SPACs

Further regulation of SPACs in the immediate future seems almost inevitable. The traditional IPO route has historically been a long road for corporate executives, requiring companies going public to disclose a considerable amount of information to allow investors to gain a comprehensive view of their financial and operational health prior to making an investment decision. Since SPACs raise money from investors before identifying their acquisition target, far less is known about the investment’s future at the time the capital is raised.

Trevor Milton, the founder of the Nikola Corporation, an American company which plans to manufacture zero-emission trucks and went public via a SPAC in June 2020, is facing criminal charges for “lying about nearly every aspect of the business.” Audey Strauss, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, said Milton was responsible for “[exploiting] features of the SPAC structure that are different from a traditional initial public offering.”

The SEC has also accused Milton of spreading misinformation directly to investors on social media regarding the company’s progress in developing certain technologies in order to generate demand for the company’s stock.

The SEC complaint filed with the U.S. District Court of Southern New York alleged that Milton posted a video to the company’s YouTube channel showcasing the company’s Nikola One, a hydrogen-powered semi-truck advertised to be capable of pulling up to 80,000 pounds. However, according to the complaint, the truck shown in the video was a non-functioning prototype of the vehicle, which was not capable of moving on its own. “The video showed the Nikola One moving down a road with text telling viewers to ‘behold’ the Nikola One ‘in motion,’ while omitting the fact that the truck was rolling down an incline due to gravity rather than under its own power,” read the SEC filing.

Shortly after issues related to the actual progress of the company became public, Milton tweeted, “Cowards run, leaders stay and fight for integrity.” Less than two weeks later, Milton voluntarily resigned as the CEO of Nikola Corporation.

This specific incident has led to more SEC warnings directed at retail investors. Gary Gensler, the SEC chairman, said in May that the agency is focusing significant resources on taking a hard look at SPACs and cryptocurrency markets, saying they currently don’t provide adequate protection for retail investors. Legislation that would require SPACs to list share warrants as liabilities on their financial statements and new provisions related to advertised revenue projections are both being considered.

While the SEC aims to harden its stance on SPACs, Sono notes that it’s still the investor’s responsibility to do their own due diligence.

“[Investors] are not doing research themselves: They’re just buying for the fame,” Sono said. “Those retail investors who didn’t leave, who didn’t do their due diligence, who didn’t research are those stuck with the SPAC that lost most of its value.”

For now, SPACs exist as a unique way for rapidly growing companies to enter public markets, but taking this avenue may prove to be a volatile ride for both investors and company management until a middle ground is reached.

“I have a high hope on it,” Sono concludes. “It could be the alternative for IPOs.”

Contact Tyler Rutherford at ruthe2tj@dukes.jmu.edu. Tyler is a senior finance major.