With the aid of computers,

mainstream animation has become more and more complex over the years as each

studio tries to outdo the other with eye-popping 3D effects. While the renowned animator Taku Furukawa has

always been open to tinkering with new technologies, at heart he has always

recognized the value of animation in its most basic form of putting pen to

paper and drawing a series of images.

Furukawa’s 2005 animated short Paper

Films (Le cinéma sur papier / ペーパーフィルム, 2005) harkens back to his exploration

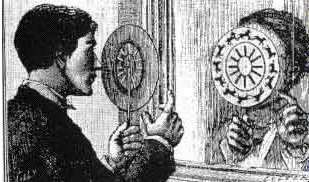

of early animation in his 1975 award-winning film Phenakistiscope

(Odorokiban/驚き版). In

Phenakistiscope, he imitated the 19th century circular spinning toy of the same

name. With Paper Films, he takes animation back to its even more ancient form of a horizontal sequence of images that depict

stages of motion.

The illusion of motion is

demystified in Paper Films as Furukawa first shows the paper pictures that make

up his animation on a gallery wall, before setting them into motion. A row of just over half a dozen images of a

sun pop up and down like ponies on a carousel.

Furukawa then moves the camera in to capture just one of the animated

images to reveal that instead the pupils of the green-nosed sun are actually people.

This pattern of showing the miniature images

in a row then moving in closer to reveal a surprise repeats throughout the

film. In one instance we see what looks

like a couple consuming a heart-shaped cake, but when the camera moves in

closer we see that it is no ordinary couple but a centaur and a mermaid. Another sequence appears just to be that of a

crescent moon lying down, but then the camera moves in closer to reveal a

naked woman popping out of the moon like Momotaro from the peach.

Paper Films is a useful film for teaching

students the principles of animation and the significance of perspective in animation. When seen in an animated sequence onscreen,

some series of images give the impression of horizontal movement. However, when the camera focuses on just one

of the series the movement appears to be vertical: a Humpty Dumpty figure

wearing an anti-war slogan on a T-shirt is not really moving sideways, but plummeting

onto a row of tanks like a bomb; a car that looks like it is moving from left to right

is actually moving from the distance into the foreground; and so on.

As ever, Taku Furukawa is having fun

with animation and he playfully drops references to historical antecedents that

shaped both his artistic aesthetic and his sense of humour – everything from Muybridge to the

Marx Brothers. The playful nature of the

film is emphasized by the lyrical score by his daughter Momoko Furukawa (official website) and

Akihiro Yoshida.

The title of this film is occasionally rendered as "Paper Film" because of the ambiguity of the katakana English title. I chose the plural "Paper Films" for the title because that is how it appears in the opening credits of the film. The plural makes sense because the 6'21" short is actually made up of many seconds long animated short films.

The title of this film is occasionally rendered as "Paper Film" because of the ambiguity of the katakana English title. I chose the plural "Paper Films" for the title because that is how it appears in the opening credits of the film. The plural makes sense because the 6'21" short is actually made up of many seconds long animated short films.

Paper Films appears on the Anido DVD

Takun Films 2.