Before the internet, there was ARPANet, an experimental government-funded prototype for a connected communications network of computers.

But before ARPANet, there was another technology called time-sharing. It was a glimpse of our own connected future—well before the dawn of the personal computer, the smartphone, or even the web.

Time-sharing was a way of computing where a user would type into a typewriter-like terminal connected to a phone line. That phone line would connect to a larger computer somewhere else in the US. The code typed into the terminal would be transmitted to the larger computer, which would run the code and then send the output back through the phone lines to the user.

The computers that we use today are far more powerful than typewriters, but it’s a similar idea when we’re typing into a program like Google Docs. We type, the data get sent to Google’s servers, and we get a response in the form of words on a digital page. Software has become more complex over the years, requiring more processing power and storage. And while computers have also gotten faster, there remain tasks that are just too difficult for a single computer to run. As a result, technology companies offer cloud computing, where data are crunched or stored by massive computers, which ends up being far more cost-effective for businesses than buying, running, and updating the databases and software on their own.

This change has made cloud computing now a hundred-billion-dollar business, and it’s only getting bigger. Amazon, Microsoft, IBM, and Google are all vying for the largest slice of providing the infrastructure for the internet of the future. But the idea of cloud computing, which is really just multiple people using the same computer hardware at the same time, has been around since some of the first computer systems.

How time-sharing began

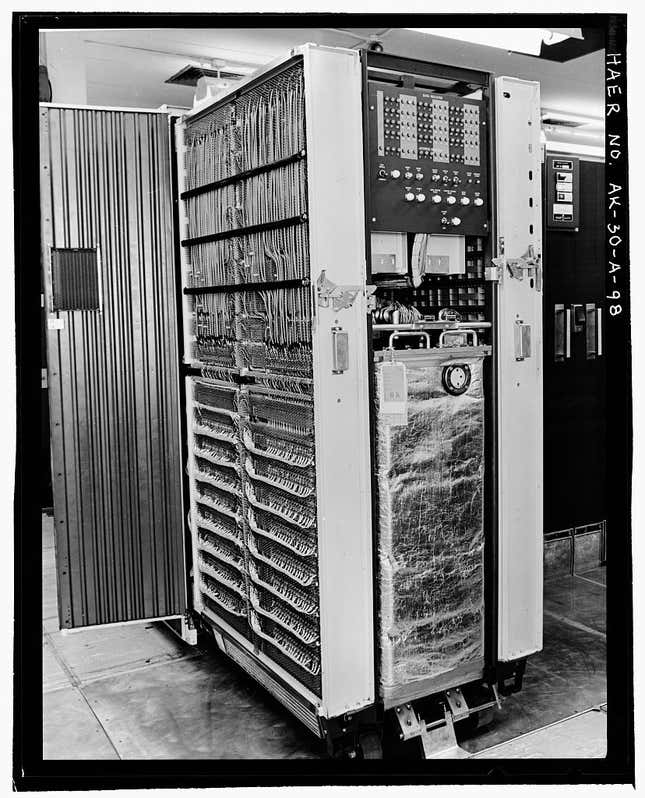

Through the mid-20th century, scientists worked at transforming the computer from a mechanical machine to an electronic one, shrinking the hardware from the size of a room to something that fit on a desk. But even these early, clunky electronic computers were still only capable of running one person’s program a time, and generally were only found at universities and government research facilities. Everyone else at the research center would have to wait until the current programmer was done, and then reconfigure the computer for their use afterward. This hassle led to the development of a process called “time-sharing,” where computers could automatically handle a queue of codes to execute one after another.

One of the first projects to tackle time-sharing was MIT’s Project MAC, which stood for Multiple Access Computer, according to 1965 MIT graduate and then Project MAC contributor Tom Van Vleck.

“Time-sharing a single computer among multiple users was proposed as a way to provide interactive computing to more than one person at a time, in order to support more people and to reduce the amount of time programmers had to wait for results,” he wrote in 2014.

This is essentially the same idea that big tech companies are using today, but the speed and scale has been exponentially increased. Instead of simple mathematical equations among a handful of researchers, billions of lines of code are being run from millions of different users on tens of thousands of servers. These servers are just high-powered computers, custom-built to work together, and still take up entire warehouses, but can accomplish many orders of magnitude more computing than their earlier room-sized ancestors.

The idea of time-sharing and linking computers together in the 1960s would be formative for decades to come. In 1962, J. C. R. Licklider, a director at the US Department of Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) funded Project MAC as a research project to build networked computers, and later directed the project. In 1968, Licklider wrote a paper (pdf) titled “Computers as a Communications Device” that would sketch out the basis of the internet and the idea of connecting computers to one another, which influenced the creation of ARPANet itself.

“It appears that the best and quickest way… to move forward the development of interactive communities of geographically separated people—is to set up an experimental network of multiaccess computers,” he wrote, referring to what would become ARPANet, which supplanted the need for time-sharing for computer researchers who had access to the network, and eventually the internet after that.

Making money selling computer processing

Time-sharing was one of the only ways to get access to computers before the personal computer was available. In the 1960s, computers were marketed to mathematicians and scientists because of their enormous cost. But with time-sharing, which could be done from long distances over a phone line, the cost of the hardware was distributed across many customers, meaning access could be cheaper. Rather than just running scientific equations or simple programs, time-sharing companies sprung up and started to offer tools that we still use today, says David C. Brock, director of the Software History Center at the Computer History Center in Mountain View, California.

“It turned out that there were other people interested in office automation, and doing things like payroll and mailings and forms and simple databases,” he said, adding that the institutions that at first were only using computers for mathematics found that they could use computers for other tasks as well.

Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak tinkered on time-sharing terminals when he was in high school, and the still-high cost of a terminal to connect to a time-sharing service factored into building the Apple’s first consumer computer, according to an interview with his co-founder, Steve Jobs.

In the years after Licklider’s paper, about 150 businesses formed in the US to provide time-sharing services, according to the Computer History Museum. Small, portable typewriters with simplistic computer chips would be rented on a monthly basis, and when plugged into a phone line, these terminals would connect to a large computer computer elsewhere in the country. Just like today’s cloud computing, customers were charged for how much computing power they used.

By 1978, the most well-known time-sharing startup, Tymshare, had a network of 450,000 sessions per month. At the time that was larger than ARPANet, the first iteration of what we know as the internet today which had dozens of connected computers, Brock said.

The 1980s saw the introduction of smaller, more affordable microchips, leading to the era of the personal computer, led by the likes of Apple and IBM. Time-sharing started to feel unnecessary, as many had now machines at their offices or homes, and didn’t need to call into a computer somewhere else to get their work done.

But it wasn’t long before the idea of “cloud computing” sprang up. In 1997, entrepreneur Sean O’Sullivan filed a trademark on the phrase “cloud computing,” according to MIT Technology Review. (The trademark is now dead.) O’Sullivan’s company was hammering out a contract with PC manufacturer Compaq, where O’Sullivan would provide the software for Compaq’s server hardware. The two would in turn sell that technology to burgeoning internet service providers like AOL, who could offer new computing services to their customers.

The first mention of the technology was scribbled in a daily planner, where O’Sullivan wrote, “Cloud Computing: The Cloud has no Borders.” Just two weeks later, Compaq predicted that enterprise software, which needed to be directly installed on users’ computers, would be usurped by cloud services distributed over the internet, what we now call “Software as a Service” or SaaS.

That’s the world we live in today. Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and IBM all offer Software as a Service products, like cloud-based accounting tools, file storage, and speech recognition, as well as “Infrastructure as a Service,” where customers can build their entire software business on the desired tech company’s servers. Much of the web is housed within Amazon’s servers, which is made painfully clear by huge internet outages when the company experiences malfunctions. The transaction is typically seen as a win-win: It reduces the cost of buying and maintaining servers for the customer, and the cloud provider can make buckets of money by efficiently running thousands of customers’ code in parallel in a server farm.

But it all started with time-sharing, and the simple idea that you could book time on someone else’s computer.