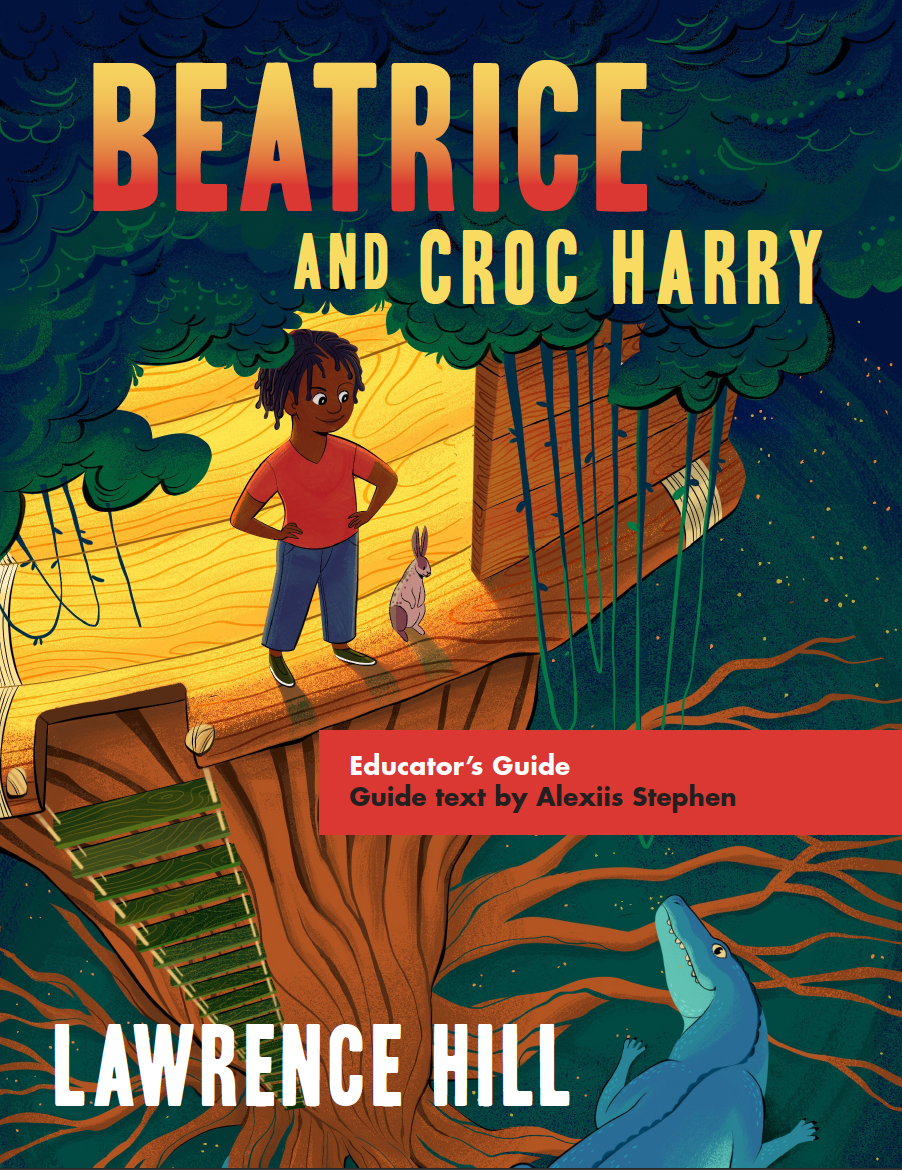

To accompany the publication of Beatrice and Croc Harry, HarperCollins hired the educator Alexiis Stephen to develop this Educator’s Guide.

Lawrence Hill’s new novel, Beatrice and Croc Harry is available in book stores and libraries across Canada.

Interview in The Toronto Star, January 8, 2022.

Lawrence Hill’s personal essay about the novel in The Globe and Mail, January 8, 2022.

Excerpt from the novel on the CBC website.

Lawrence Hill’s 11th book, the novel Beatrice and Croc Harry is for children and adults. It will be published on January 11, 2022 (HarperCollins Canada, 375 pages).

Watch the trailer here:

Lawrence is thrilled to be the guest curator at the 2021 Vancouver Writer’s Fest. He is curating events featuring these writers:

October 18: Lisa Bird-Wilson and Katherena Vermette

October 21: Cherie Jones and Myriam Chancy

October 22: Cheryl Foggo and Karina Vernon

October 22: Ben Philippe and Ian Williams

October 23: Chantal Gibson

Lawrence Hill is delighted to announce that HarperCollins Canada will publish Beatrice and Croc Harry in January 2022. It’s his eleventh book, and his first novel for children. It will be marketed to children aged 9 – 14, but Lawrence hopes that it appeals to readers of all ages, adults included! He, for one, still love novels for children! The novel emerged from bedtime stories that Lawrence used to tell his fifth and youngest child Beatrice. About 375 pages, it features a young girl named Beatrice who awakens alone and with complete amnesia in a massive forest, and her tempestuous relationship with a hyperverbal, 700-pound crocodile named Harry. The two embark on a journey so Beatrice can attempt to discover her lost identity.

For an excerpt from Beatrice and Croc Harry, read the CBC article here.

Lawrence was commissioned by Obsidian Theatre’s artistic director Mumbi Tindyebwa Otu to be part of an anthology of 21 filmed short plays by Black playwrights across Canada called 21 Black Futures to draw on the breadth of the Black experience in Canada and to explore the question, “What is the future of Blackness?” Lawrence’s play Sensitivity explores the state of mind of Gabriaela Monk, a forty-something business professional, after she is fired for leading a racial sensitivity training seminar that goes terribly awry.

21 Black Futures will available for free streaming on CBC Gem until February 2022.

Watch the trailer here.

Watch the play here.

Related News Articles:

CBC

Globe and Mail

Now Toronto

In November 2020, Lawrence Hill received an Honorary Doctorate Degree from the University of British Columbia. Watch Lawrence’s commencement speech here.

Photo taken by Ron Scheffler

Lawrence Hill shares a personal reflection about his later father, Daniel G. Hill III (1923-2003), and about his own life as a father. It first appeared last year in the essay collection Forty Fathers: Men Talk about Parenting, edited by Tessa Lloyd. Read it online here.

Lawrence Hill writes about his family’s long-standing boycott of Aunt Jemima syrup and pancake mix. Read his opinion piece online in the Globe and Mail celebrating the elimination of the Aunt Jemima brand of products.

Lawrence Hill seeks guidance from his late father in the wake of anti-Black violence. Read his imaginary letter in Maclean’s magazine.

Boochani — a Kurdish Iranian scholar, poet and journalist — has written a haunting account of how Australia has been punishing him and hundreds of other asylum seekers by detaining them for nearly six years on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea. Read the review by Lawrence Hill online in the Globe and Mail or in the print edition on Saturday June 8, 2019.

In April 2019, Lawrence Hill received the Library and Archives Scholars award along with Shelagh Rogers, Marie-Louise Arsenault, Ronald Cohen, and Frances Itani. Read about it on CBC.

Written by: Belinda Sutton, Ontario Ministry of Labour

The following article appeared on January 7, 2019 on the Ministry of Labour’s internal employee website.

Daniel Hill, circa 1980

A Chatham boathouse owner got more than he bargained for when he refused to rent fishing boats to Black people. He got to experience the powerful determination of Daniel Hill, Director of Ontario’s Human Rights Commission.

It was the 1960s and Mr. Hill had been recently hired by the Department of Labour to start up the commission. His job included spreading the word about its services, investigating complaints of discrimination and seeking justice for victims.

Mr. Hill quickly jumped into action when he heard about the boathouse owner. He convened a public hearing in Chatham, and used his influence and deft recruiting skills to transform it into a community event. When the owner arrived, the first thing he noticed was almost everyone in the room was Black.

During the hearing, Mr. Hill put the boathouse owner through a gruelling cross-examination. The man soon wilted and promised to change his racist rental policy. But Mr. Hill didn’t trust the man’s resolve. He called for an adjournment and pulled some Black audience members aside. He immediately arranged for them to put down deposits on fishing boats for the summer. Some of them refused, saying they didn’t like to fish. But Mr. Hill would hear none of it. “That’s irrelevant,” Mr. Hill told them. “You’re going fishing, and that’s that.”

Mr. Hill’s tenacity paid off. The commission won the case. From then on, Black people were able to rent fishing boats from the boathouse owner.

This anecdote is one of many told in an autobiographical book by Mr. Hill’s oldest son, Dan, who is a Grammy Award-winning, singer-songwriter. The book is entitled, I am My Father’s Son: A Memoir of Love and Forgiveness. In part, it chronicles Mr. Hill’s pioneering of human rights in Ontario.

Daniel Hill with his family in 1976

First of its kind

The Ontario Human Rights Commission was created in 1961. This made Ontario the first jurisdiction in Canada to formally recognize the moral, social and economic consequences of discrimination. No other human rights commission existed in Canada at the time – not even at the federal level. In those days, racism and discrimination were rampant against Black people, Jewish people and others. The commission’s mission was to advocate against discrimination of people based on race, creed (religion), colour, nationality, ancestry and place of origin.

Mr. Hill was hired as the commission’s first director. The commission was part of the Department of Labour.

“Dad was very devoted to the cause of overturning discrimination and racism,” Dan says in an interview. “That was his passion. He encountered a lot of discrimination in the American army between 1940 and 1945. It made him very hungry and eager to overcome racism and discrimination.”

Rabble Rouser

Dan describes his father as a “perfect fit” for the commission which, in the beginning, consisted of just two employees – Mr. Hill and his secretary, Madeleine Smith. His father built the commission and its cause from its early days, Mr. Hill says in his book.

“He was a rabble-rouser who loved confrontation,” says Dan, the oldest of Mr. Hill’s three children. “Better still, because he was building the commission from the ground up in a country where no such agency had previously existed, he didn’t have to worry about following existing structures or protocols.”

Not one to hang around the office waiting for the public to come calling, Mr. Hill would jump into his rusted-out, grey Volkswagen Beetle – “the antithesis of civil servant bureaucracy” – and drive across Ontario. He brought the message of human rights to the people, setting up local offices and investigating cases of alleged discrimination. He was on the road up to 10 days a month.

Mr. Hill’s younger son, Lawrence, says: “He believed the services of the Ontario government should be taken to the people – that you shouldn’t just sit back and languish, waiting for somebody to wander into the commission and lodge a complaint.”

His father was especially committed to providing services to First Nations people, he says in an interview at a Hamilton coffee shop. “He used the term storefront operations – he liked to extend the services to, and hire, people in local communities to reach out to people on the street.”

Like his brother, Lawrence, an awarding-winning author, has written an autobiographical book that contains many stories about his father. The book is called, Black Berry, Sweet Juice: On Being Black and White in Canada.

Daniel Hill with son Lawrence in 1957

Background

Born “Daniel Grafton Hill III” in 1923, Mr. Hill was descendent from Black slaves in the United States. His father and grandfather were university-educated ministers in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

“His slave ancestry gave him a good sense of oppression and helped him develop a strong sense of social justice,” Lawrence says in a June 1, 2003 Globe and Mail article.

Mr. Hill’s disgust for racism and discrimination grew as he experienced discrimination firsthand growing up in Missouri, and later, through segregation when he served in the American Army during the second world war. This treatment led to him becoming disenchanted with living in the United States.

“He often recalled with bitterness that Black men were deemed good enough to die for their country, but not to live on an equal footing with other Americans,” Lawrence says in the article.

After the war, Mr. Hill received a Bachelor of Arts degree from Howard University in Washington, D.C., and soon began turning his sights north of the border. He saw Canada as a “blank slate, a new world on which he could project all his ambitions and dreams of glory, without any of the baggage that defined his country of origin,” Dan says in his book.

In 1950, Mr. Hill moved to Canada to study sociology at the University of Toronto. In 1951, he received his Master’s. Two years later, Mr. Hill married Donna Bender, a White American civil rights activist and sociologist who shared his passion for human rights and who was instrumental in supporting him throughout his life’s work in the cause. Their children, Dan, Lawrence and the late novelist Karen Hill, were all born in Canada.

In 1962, Mrs. Hill heard the human rights commission was looking for a director. She thought her husband would be perfect for the job. A sociologist and recent PhD graduate, Mr. Hill had just written a trailblazing thesis, Negroes in Toronto, that looked at patterns of immigration, employment, where Black people lived and how they integrated socially.

“Mom actually put the bug in the ear of another civil rights activist and said: I see the human rights commission is looking for a director – how about Dan?” says Lawrence, a creative writing professor at the University of Guelph. “And I think that guy put the bug in the ear of somebody in the government.”

“Dad was a good candidate because he was an expert in Black history in Canada and he had this newly-minted PhD. And he was a Black man himself with a civil rights engagement.”

Daniel Hill and wife Donna Bender in 1953

Commission roots at the Department of Labour

The Ontario Human Right Commission evolved from human rights legislation in the 1940s. It grew from rising social activism, union activity that focused on human rights and Canada’s post-war immigration policy that led to a major flow of non-British immigrants in the 1950s. At the same time, rapid economic growth allowed a growing middle class to examine social justice issues. This added fuel to a struggle for human rights.

Here’s the timeline in Ontario:

· 1944: passing of Ontario’s first human rights legislation, the Racial Discrimination Act, which prohibited the publication or displaying of any notice, sign, symbol or other representation expressing racial or religious discrimination

· 1950: adding a section to the Labour Relations Act that outlawed discrimination in collective agreements

· 1951: enacting the Fair Employment Practices Act, which prohibited discrimination in employment on the basis of race, creed, colour, nationality, ancestry or place of origin

· 1951: enacting the Female Employees Fair Remuneration Act, which outlawed discriminatory pay rates against women, requiring them to receive equal pay for equal work

· 1954: enacting the Fair Accommodation Practices Act which prohibited discrimination on grounds of race, creed, colour, nationality, ancestry or place of origin for services, facilities and accommodations in public places

· 1958: enacting the Ontario Anti-Discrimination Commission Act that established a commission within the Department of Labour to publicize all of Ontario’s human rights legislation

· 1961: changing the name of the Anti-Discrimination Commission to the Ontario Human Rights Commission

· 1962: repealing most of Ontario’s human rights laws passed in the 1950s, paving the way for the new Ontario Human Rights Code

All of the key pieces of human rights legislation introduced in this era (with the exception of the 1944 Racial Discrimination Act) fell under the jurisdiction of the Department of Labour. The commission remained under Labour until 1987 when it was moved to the Ministry of Citizenship and, in 2003, to the Ministry of Attorney General.

Daniel Hill receiving the Order of Canada

Hate calls and threats

Mr. Hill headed the Ontario Human Rights Commission for 12 years. During that time, he investigated many cases of discrimination, never losing his fervor to break down barriers and battle racist practices such as a refusal to hire or rent accommodations to visible minorities. He and the commission were often in the news – generating hundreds of headlines and news stories over the years. The commission won most of its cases.

“He encouraged people to make complaints,” Lawrence says. “He made people aware of what the reach of the Human Rights Code was.”

Sometimes, Lawrence says, people didn’t like the work of the commission. Angry, they would target Mr. Hill and his family.

Both Lawrence and Dan recall receiving hate calls at home and comments from irate neighbours. Some people shouted and swore. Others behaved worse.

“We had some death threats so, as children, we weren’t allowed to answer the phone,” Dan says. “There were threats of our house being bombed and threats we might be shot.”

Lawrence explains: “There were people who despised the idea of advances in human rights. There were racists in the province. There were people who had very negative views about the notion of enshrining human rights in provincial legislation.”

Lawrence says some people may also have been infuriated that an American was running the human rights commission even though Mr. Hill became a Canadian citizen.

Making an impact

Dan describes his father as a very strong, proud and authoritarian man who could be very charming and win people over with humour. “He used his charm to diffuse difficult situations.”

He says his father’s work at the commission had a profound impact on him and his family.

“It made us realize that we could never take anything for granted – that there was racism in our society and we had to do everything we could to overcome it.”

In 1971, Mr. Hill was appointed chairman of the commission. He took over from Louis Fine, who retired. Two years later, Mr. Hill left the commission to create Canada’s first human rights consulting firm. Later, he and his wife founded, as volunteers, the Ontario Black History Society. In 1981, Mr. Hill published The Freedom Seekers: Blacks in Early Canada, a popular history book that remained in print for nearly 20 years.

In 1984, Mr. Hill was appointed Ombudsman of Ontario, a post he held for five years until his retirement in 1989. A decade later, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada. Suffering from poor health in his later years due to diabetes, Mr. Hill passed away in 2003. He was 79.

Of his father’s work, Lawrence says: “I feel he was a visionary leader in a field of great significance to Canadian society. I think he had a profound impact on our institutions, attitudes and behaviours – individually and collectively.”

Dan says: “I’m impressed and very proud of my father’s legacy. It’s very romantic and very powerful how he started the human rights commission and built it from the ground up driving in his Volkswagen Beetle across the province investigating discrimination.”

Lawrence says his father forged many alliances with Jewish, Indigenous and other activists over the years. These ties were instrumental in his efforts to promote human rights.

“He was a ground-breaking activist moving Ontario in the direction of protecting human rights when it had never done so before,” Lawrence says. “Ontario thus became a leader in the field of human rights protection, for the enactment of legislation and for the investigation of complaints.

“If it hadn’t have been for the human rights commission and the pioneering human rights work of the 1950s, we wouldn’t be here today enjoying the protections of human rights that we currently do.”

Lawrence travelled with his mother, Donna Hill, to Switzerland where she went to die on May 17, 2018. His personal essay about their journey and about his mother’s life and death appeared online in the Globe and Mail on June 1, 2018 and in the print edition on June 2. Read about their journey to Switzerland, and the life that brought them there.

Lawrence joins visual artist, writer and educator Chantal Gibson for an on-stage conversation on the SFU campus in downtown Vancouver on April 27, 2018. Watch the evening of reading and conversation with Lawrence Hill and Chantal Gibson on YouTube here.

Le Sans-papiers, the French translation of The Illegal, has been shortlisted for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Translation. Congratulations to the translators Carole Noël and Marianne Noël-Allen for their marvellous work. Montreal-based Les éditions de la Pleine Lune published the translation in 2016.

Lawrence Hill has been named one of two recipients of the 2017 Canada Council for the Arts Molson Prize, for outstanding contributions to the arts. Kent Roach also received the award, for outstanding contributions to the social sciences and humanities.

Lawrence Hill's review of Omar El Akkad's novel American War appeared on April 1, 2017 in The Globe and Mail.

Lawrence Hill has been selected by the Writer's Trust of Canada for a Berton House residency. Hill will live and write for three months in the winter of 2018 in the childhood home of Canadian literary icon Pierre Berton in Dawson City, Yukon. Congratulations to the writers Elizabeth Ruth, Wendi Stuart and Sandy Pool, who have also been selected for Berton House residencies in 2017-2018.

The Illegal, Lawrence Hill's fourth novel and tenth book, is among the 17 Canadian books longlisted for the 2017 International DUBLIN Literary Award.