This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In the decades she lived her life before she came out as trans, at 66, the writer Lucy Sante constructed a sort of decoy self to get by in the world. The aloof downtown intellectual, named Luc by her Belgian parents, is a poetic essayist with a magpie mind and a talent for archive spelunking. Her books — among them Low Life, The Other Paris, The Factory of Facts, Kill All Your Darlings, and Maybe the People Would Be the Times — are in many ways books made out of other books, close readings that conjure lost worlds. Sometimes she would lose herself: As she wrote in the preface to Low Life, her 1991 history of Manhattan’s slums, and slumming, “At least once, late at night, and under the influence of alcohol and architecture and old copies of the Police Gazette, I staggered around looking for a dive that had closed 60 or 80 years before, half expecting to find it in mid-brawl.”

But Sante never wrote much about her feelings. Her guard was always up, an observer. Photographs of the writer, from the ’70s and ’80s, in the prime of Sante’s punk-flâneur cool, vibe a kind of reticent disdain — receding hairline, sunglasses, Gauloises-smoking, never, ever smiling. It was, by all accounts, to her friends, colleagues, students, and romantic partners a mostly convincing presentation, difficult in some ways to untangle from her writing. Certainly, it inspired many readers to admire Sante’s unsentimental erudition and seek to emulate it.

But Sante herself had never been fooled by this Luc character — “saturnine, cerebral, a bit remote,” who came “very close to asexual despite my best intentions” — whom she built for a reason and always felt trapped inside. She was a little miserable. Three years ago, as mass coronavirus vaccinations were just rolling out, Sante was stuck at home in Kingston, going on long walks with her dog and watching The Queen’s Gambit. She’d had a “very snug year” with Mimi Lipson, a writer and stained-glass artist who’d been her partner of 14 years, though changes were afoot. For over two decades, Sante had lived upstate, teaching writing and the history of photography at Bard College while raising her son, Raphael, with her ex-wife and freelancing, notably for The New York Review of Books. But Raphael was in college at Bard, and Sante was looking forward to retiring when he graduated in 2023. She had negotiated to sell her papers to the New York Public Library and “realized, dimly, that I was preparing for death.”

There were other frustrations: She hadn’t gotten much traction on the biography of Lou Reed she’d received a big book contract to write after his death in 2013 — she knew Reed, just as she knew pretty much everyone worth knowing in the now-mythic punk-bohemian grit-and-glitter firmament of downtown Manhattan, and Andrew Wylie (who is not her book agent) had called her up with the idea, convinced that she was just the right person for the job. But the sort of quote-wheedling intimacy arbitrage of celebrity biography was never really her talent or interest.

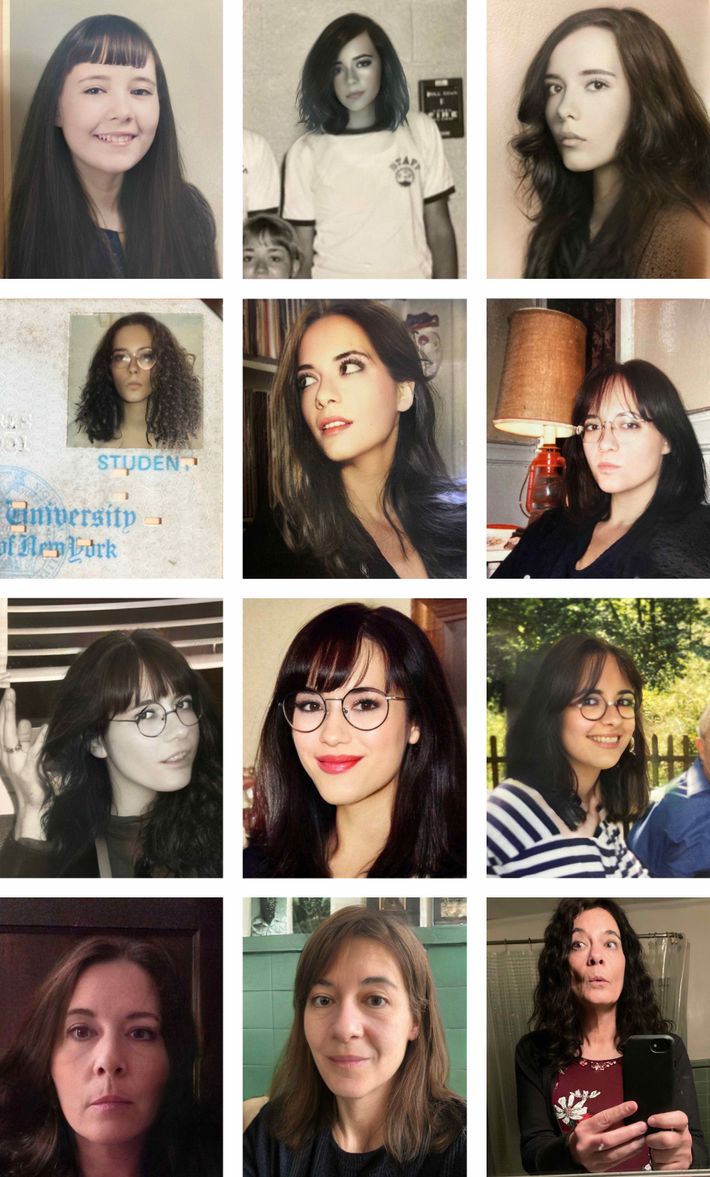

Then, on February 16, 2021, curious and a bit bored, Sante downloaded FaceApp on her phone and, much to her surprise, using it broke her open. “Although the app allowed users to change age, shape, or hairstyle, I was, specifically and exclusively, interested in the gender-swap function,” she writes in a new memoir, I Heard Her Call My Name, which will be published almost exactly three years after that fateful download, on Valentine’s Day Eve. “I fed in a mug-shot-style selfie and in return got something that didn’t displease me: a picture of an attractive woman in whose face my features were discernible.” She fed more in — “every image of myself I possessed, beginning at about age 12.” What emerged was an alternate record of her life in which Sante had a much better time as a girl.

The first person she told, after her therapist, was Lipson. “She sat me down and showed me a picture of this nice-lookin’ lady sitting at our breakfast nook,” says Lipson. “And I was like, ‘Oh, who is that?’”

“She showed me another and another,” Lipson tells me. “She had to show me five or six pictures and tell me that they were her. She thought the whole story would become apparent, but I didn’t know who they were. To me, they were just a bunch of pictures of people I didn’t know.”

“There are many reasons why I repressed my lifelong desire to be a woman. It was, first of all, impossible,” Sante writes in the book. “My parents would have called a priest and had me committed to some monastery, lettre de cachet style. And the culture was far from prepared, of course. I knew about Christine Jorgensen when I was fairly young, but she seemed to be an isolated case. Mostly what you came across were aggressively vile jokes from Vegas comedians and the occasional titillating tabloid story.”

Now, though, Sante plunged headlong into her coming out. She sent emails to several rounds of friends — the original subject line was “A bombshell” — describing the FaceApp revelation and the urgent possibility it opened up for her. The reintroduction of Luc as Lucy would be a bit of a shock to many of her friends. As one who has known her since they were undergraduates at Columbia, the writer Darryl Pinckney, tells me, “Everything Lucy says about what was going on internally was, of course, a surprise.”

“It was kind of out of the blue,” says another friend she’s had since college, the filmmaker Jim Jarmusch.

There was worry, too, Sante felt, besides the discomfort of astonishing her friends with the news: What would happen to her byline, her literary brand? Could she come out without risking everything she had built? Then there were the practicalities, how she should dress and walk and wear her hair. Other than some Bard students, she didn’t know many trans people to model herself on.

Yet her friends immediately noticed how much more unfettered Lucy seemed. “She always had, as Luc, a dark side and moody side,” says Jarmusch. “But she has been relieved of something — a light is spilling out.”

“I can’t remember Luc smiling in a photograph,” says Pinckney. “But Lucy does, and that, I think, is the story.”

Sante isn’t smiling, exactly, when she picks me up at the train station in Rhinecliff one chilly January afternoon. She is vaping and dressed like a bookish rocker in advanced middle age, wearing an olive cardigan and her ashy-blonde hair — a wig styled by, according to the new book, Love Hair in Kingston — to her shoulders with bangs. Driving up River Road in her sensible car to the bridge that crosses the Hudson, she points out the low stone wall that runs continuously along the shoulder and how this, the eastern side of the river, was originally “Tory,” home to the mansions of the rich, who liked the view across the river to the Catskills, while her neighborhood on the other side was traditionally working class. That economic division continues to this day, she says: Jann Wenner once fought to build a helipad on his nearby estate.

By the time we get to her house, which was built in 1929 (“A bit later than the others around here,” she says) and has a nice deep porch from which one could observe a neighbor’s incongruously jacked-up pickup at a safe distance, she has already told me about a friend of hers who grew up in the building I used to live in on St. Marks Place — Sante has an almost unnervingly good memory; friends say she can always recall where they first met and with whom — and given me a condensed history of Kingston’s booms and busts.

Inside Sante’s house, the walls are crowded with paintings, collages, and flea-market gleanings. There are shelves of books and painted signs and folk-art figurines and lots of spooky old black-and-white photography. “Everything here has a story,” she offers, and when I ask her to tell me one, she says, “Dang, where should I start?,” before pointing to a small framed piece by the fireplace. “This is a Basquiat” — it’s a collage that incorporates a photo-booth self-portrait — “one of the color-Xerox postcards he made. It’s been disputed but not successfully. I am pretty sure he only made one each and destroyed the original. We were sitting on the metal stairs of this bar on St. Marks, and he was selling them for two bucks.”

She jokes while showing me her basement office that it was the loft she had always wanted with the shelf space she needed: “Really, until the pandemic, I was telling people in the city, struggling in small apartments, ‘You should move to Kingston.’ You could still, at the time, buy a house for under a hundred thousand dollars.”

More so than for many writers, Sante’s is a syllabus self. To read her is to know she has done more interesting reading than you have. She told The Paris Review that a riff from Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell — “I loved maudlin pictures, the painted panels over doors, stage-sets, the backdrops of mountebanks, old inn signs, popular prints; antiquated literature, church Latin, erotic books innocent of all spelling, the novels of our grandfathers … inane refrains and artless rhythms” — “was virtually the template for my entire life!”

“She’s not overtly social,” says Jarmusch. “And yet she is an anthropologist of social phenomena.” This doesn’t often require her to stray far from her meticulously organized basement library and the green table she uses as a desk, which traveled north with her decades ago from the East Village. She has written all of her books on it.

Sante has always seen herself as an outsider. An only child, she was born in 1954 in Verviers, Belgium, where generations of her family, Catholic and Walloon, had been employed in a textile industry that dated back to the Middle Ages. When she was still in grade school, the family had immigrated to New Jersey. Her father, who once wanted to be a writer, worked in a Teflon factory, and her mother, who had lost an infant daughter before Sante was born and with whom Sante had a contentious relationship, worked in a high-school cafeteria.

In those immediate postwar years, Belgium felt stuck in the past, while America was rushing confidently into the future. Sante, who didn’t know English when she arrived here, had to be a quick study to survive and tried to decode the mores and customs of her new country and her peers. She wasn’t much for sports, but she ransacked her local public library in New Providence. Her intellect clearly stood out. The nun who taught Sante in eighth grade recommended she take the test to get into the prestigious, tuition-free, Catholic Regis High School in Manhattan.

Regis, an all-boys school, “was not known for producing artists,” she writes in her new memoir. “I did meet new kinds of people: conservatives, libertarians, future priests, prototypical nerds, and, most interestingly to me, kids who were clearly gay.” (She herself has never been sexually attracted to men.)

After school, she began to explore downtown, which was then in its hippie dénouement. She was eventually kicked out of Regis for flunking algebra and Greek, not to mention some unexplained absences, and she had to finish up at her local Jersey high school. She continued her reading: Thomas Pynchon’s V.; an anthology called Writers in Revolt, which was a tasting platter of then-radical literature by the likes of Genet, Céline, Burroughs, and Ginsberg; music magazines like Crawdaddy.

Upon graduating, she got a full scholarship to Columbia University. The way Sante always saw it, in the wake of years of student unrest, fewer of the legacy students enrolled, which meant the school took more chances on oddballs like her. There, she and Pinckney briefly ran the literary magazine.

Sante thought she would always live in Manhattan and likely on the margins in some way, maybe working at a bookstore, as she did at the Strand right out of school, before Barbara Epstein hired her as her assistant at The New York Review of Books. “I always thought, Well, I’m never going to be successful enough to afford anything, but I can always find a cheap apartment and bookstore jobs or whatever as a fallback,” she says. “I really thought that would be my life.”

Her 20s were spent in a long-lost low-cost city — “It was a ruin in the making,” she wrote in the afterword of Low Life, and “I was enthralled by decay” and the “dance party going on around the flames.” Her friends were filmmakers, photographers, and musicians.

Living in the East Village, “I would go run a simple errand and run into nine people,” Sante tells me while seated at the other end of her beige sofa in Kingston. “It used to be like it was high school. It was crazy.” She even lived in a famously bohemian, poet-filled building on East 12th Street for years, downstairs from Ginsberg.

“We loved New York because you could be as unusual or strange as you could imagine and walk down the street and see someone stranger,” says Jarmusch. It was “this wild place” where they could live with no money, stay out all night, and furnish their apartments with castoffs from the street. Their tastes were also scavenged. “We loved crime novels and film noir and Dadaism and William Burroughs,” Jarmusch continues. Also: Brecht, reggae, Walter Abish, Walter Benjamin, Blaise Cendrars, and Algerian wine.

“We were all interested in shifting personae,” says Jarmusch. In his memoir, Come Back in September, Pinckney says he and their friend the singer Felice Rosser (both of whom are Black) would call Lucy by the “Black nickname” Earle.

They were young smart people with strong opinions. “We had knock-down, drag-out fights about who liked what and why,” says Pinckney. In Come Back in September, Sante is depicted as disputatious and often lovelorn, having once declared, “How come everyone else wins the sweepstakes? I fuck with my emotions the way a stunt driver fucks with his body.”

In 1981, while working as Epstein’s assistant, Sante published her first essay in the Review — on Albert Goldman’s biography of Elvis Presley (which she found all “innuendo and fake outrage”). By the time she was 30, in 1984, she had quit to write.

Freelancing was tricky even back then: Sante supplemented writing with copyediting for Sports Illustrated. It helped that rent on that two-bedroom apartment on 12th Street was $162 a month — that is, when she and the other tenants weren’t on a rent strike to protest various landlord misdeeds. Her partner from 1983 to 1990 (for the last three years, they were married) was the poet April Bernard, who worked as a glossy-magazine editor. As Sante recalls in her new book, “We ate at restaurants where you were served seven squid-ink ravioli on a plate the size of a bicycle wheel, wore clothes with shoulders that extended three inches past that corner of the body, were always onto the new thing six months before the general public, went in on group summer-house rentals in eastern Long Island, went out for brunch and tried fad cocktails and knew the names of liquor-company publicists.”

But something was always off. The life Sante found herself in seemed chosen for her, somehow not as she’d intended it to be. Some of this dislocation was apparently frustrated ambition. Sante told The Paris Review that “the ’80s were really hard for me because three of my friends, three pretty close friends, almost simultaneously became world figures. Jim Jarmusch, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Nan Goldin. And I thought, I’m fucked, they did it, I didn’t, bye, see you later.”

Sante got the idea to write Low Life in response to how the “living ruin” of downtown that she had cavorted in for over a decade was beginning to change. She wanted to know what had been there before, Ouija-ing the neighborhood’s ghosts and demons before gentrification would exorcize their wails and cackles forever. At the time, she thought of Low Life as little more than a “potted history,” which she would publish while working on what had to be her true artistic purpose: a novel.

As Sante wrote in its preface, Low Life could “be seen as an attempt at a mythology of New York,” one “not tied to commerce or public relations but resident in the accumulated mulch of the city itself.” At least two generations of well-educated post-suburbanites planted in it some idea of themselves and the reason they’d moved to a crappy tenement in the East Village. Low Life was a book that evoked a place of risk, where “ecstasy” was “purchased at the cost of death.” (Rereading Sante, I kept coming upon notions I thought I had come up with on my own but that I had in fact ingested from her years back.)

Sante followed Low Life with a volume of early-20th-century crime photographs, called Evidence, which features many dead bodies. Spy magazine hired her to be its crime critic. Later, Gangs of New York hired her as a historical consultant to get the olde-tyme mayhem just right. Her fascination with the urban gothic has continued. Her 2015 book, The Other Paris, was written as a reminder that cities used to be “vivid and savage and uncontrollable.”

She never became a novelist, but Low Life turned Sante into, as her second wife, the writer Melissa Holbrook Pierson, once put it, an “‘It’ personage.” Its publication, and success, coincided with the couple’s leaving the East Village. Sante and Pierson met and married in 1992, the year after Low Life was published. The troubadour of the Bowery saloon now found herself living in Park Slope, where “one of the big shocks for me,” Sante says, was “Wait a minute — how can this be a city when there’s no street theater? ” From Pierson’s perspective, as she would later write, they were now “on the cusp of potentially impressive careers with an endless supply of ever-more-impressive people to befriend.”

Sante credits Pierson with moving them upstate. “I didn’t realize that — it took me years to figure out that she was moving me out of the city by degrees,” Sante says, “dividing our time, as they say,” with their place in Brooklyn. Pierson felt they were just being practical. The couple had Raphael in 1999 and shifted their lives fully upstate.

But Sante was restless. She met Lipson in 2007 in an invitation-only Google group called the Hermenautic Circle. (Lipson didn’t know who Sante was — “I had never heard of her before,” she says. “I was living outside that cultural stratum, which I think was refreshing to her.”) It was limited to 100 members. Many were academics. Sante found Lipson, according to the memoir, “smart and funny and quick and passionately attentive to language and visually alert and endowed with an impressive array of manual skills.” They got to know each other just as Sante’s marriage was falling apart.

Sante and Lipson started dating. Their life was quiet; Sante still claims to have almost no friends in Kingston. “I’m the kind of person who has hundreds of friends but isn’t very close to very many people at all,” she tells me. (In the book, she said that she rarely called people on the phone though has started to more since she came out.)

Her social activities included things like getting together with a group of guys at the writer Joe Hagan’s house in Tivoli and playing records for one another. Sante, as someone of obscure, cosmopolitan enthusiasms, seemed to fit in fine.

“I start out as a fanboy,” says Hagan. “Low Life, that is required reading in my universe.” When he read a 2022 story by Sante in Vanity Fair — in which she wrote, “I didn’t know how to act as a man. I hated sports and dick jokes and beer chugging and the way men talked about women; my idea of hell was an evening with a bunch of guys” — Hagan started to worry, Did she mean us? (She later reassured him about their friendship.)

Sante has always been skeptical of the memoir form, at least as it is usually — and, to her mind, tackily — practiced: as a tell-all, confessional blurt. She has never even kept a diary, once noting that “you might say there are two kinds of writers: those who keep a journal in the hope that its contents might someday be published, and those who do not keep a journal for fear that its contents might someday be published.” She was always the second type. She thought of the task of writing her own autobiography as an “interesting intellectual, artistic exercise,” but, she says, “most people have a hard time getting sufficient distance from their own miseries. It just becomes about upchuck or something.”

But she had written a memoir. The Factory of Facts was published 26 years ago and leaned hard into being an interesting intellectual, artistic exercise; it took inspiration partly from Nabokov’s Speak, Memory. It is not particularly revealing about Sante’s deepest yearnings, but it explicates her family’s history and talks about how ungrounded she always felt after moving to the U.S. as a child: “Emigration, like a natural upheaval, sheared my foundation when the ground was soft, laying open expanses of strata.”

The book opens with a deliberate deflection — nine alternate versions of her life, quickly sketched out, including one in which she ends up as a priest working in the propaganda office of the Holy See and another in which she ends up a junkie in Goa, where she “contracted scabies and syphilis, but I didn’t care.” None of those alternate lives involve her being a girl.

She tells me she wrote that book for her father to read: “But by the time it was done, he had dementia, and my mom would read it page by page and call me and yell at me for things I got wrong.”

“Her story for a long time was she would have written a different book if her parents weren’t around,” says Lipson.

“For me, The Factory of Facts and I Heard Her Call My Name were written by the same writer,” says Pinckney. “One was about the development of a sensibility. And this is the wizard behind the curtain.” The new memoir, which is named after a Velvet Underground song, also solved another problem: Sante was able to substitute it for the incomplete Reed biography, paired with a book about New York in the 1960s.

When Sante came out over a series of emails and then launched a revamped Instagram full of selfies, people who had known her for decades began to reevaluate everything they thought they knew of her. Responses, Sante writes, ranged from “‘unexpected but not surprising’ and ‘surprised but not surprised’ and ‘shocking but not’ at one end, and at the other were a few people who reacted as if they’d been hit by a train while they were looking the other way. Those tended mainly to be guys who over the course of many years’ friendship had come to think of me as a sort of mirror or alter ego, so reevaluating me meant having to reevaluate themselves.”

“My first response to her email was that this was one of her fictional personas,” recalls writer Annie Nocenti, who has known Sante for around 30 years. Still, “suddenly, things in our past made sense. When I would have parties upstate, all the guys would go over to the firepits and roll the joints. There would always be that sort of gender cliché. Lucy would go inside with us and clean up. Lucy’s gentleness — suddenly it made sense that she was female. It clicked.”

Jarmusch is entirely supportive but seems to be still intellectualizing it. “Lucy has always been uncovering ghosts and duality and masking and style of presentation,” he says. “In an aesthetic sense, she has always been more attracted to deception than desire.” Then he pauses, considering: “I don’t even know what that means.”

In the end, her coming out broke up her relationship with Lipson. “Apparently, I was in this lesbian relationship,” Lipson says wryly. But seeing how much happier Sante was made it easier to get used to. One thing she has learned about dysphoria is “it’s almost as if Lucy’s color spectrum includes a color I cannot see,” she says. “I don’t have the imagination to see it. So I have to take her word for it that it is there.”

Sante’s son, Raphael, who graduated from Bard in May, didn’t seem much bothered by it. Sante chalks that up to the fact that his generation has few hang-ups about gender and that Raphael was very active in larping in middle school. “He’s known trans kids since he was 11,” she says.

“I understand there is not just a line in the sand but a deep walking through the looking glass,” says Pinckney, still chewing it over himself. “However, Luc was more real than Lucy thinks. Nobody loved Luc as an abstraction. That was a very real person. And Lucy is for herself this completed person, but she has always been real, gender aside, because the mind is so extraordinary.”

In The Other Paris, Sante wrote, “Everything is always going away, every way of life is continually subject to disappearance, all who reach their middle years have lost the landscape of their childhood, everyone given to introspection feels threatened.” Now, somehow, as Lucy, which is to say finally as herself, she has another chance — if not quite a do-over exactly, then a rereading, which seems appropriate.

In 2020, she published a book of essays called Maybe the People Would Be the Times but, because of the pandemic, never promoted it with a tour. By the time she did, it was the fall of 2021 and she had already started transitioning. She would sometimes begin a reading with a poem that she wrote at 24 called “Easy Touch,” which includes the lines “It was the beginning of a new dream which was real life, or the manifestation of an old one at its cusp … So strange to be someone lifelike but too early.” Now she is convinced it was actually about transitioning.

When she retired last year from Bard, she was awarded a captain’s chair with her chosen motto on it. It’s in her house in Kingston (where it is getting late; we’ve been speaking for hours). “It was a delight to hear President Botstein read this aloud from the stage: ‘Despite fluctuations in the price of beef, the sacrifice remains constant for the ox — Karl Marx,’” she says, laughing, and in case I didn’t get the point, says, “I’m an ox.”

Not that, she quickly adds, Bard was a terrible place to work. But she will soon turn 70. It was time to turn that page. “I also, this year, retired from freelancing; in 2023, I suddenly decided I have had fucking enough. I started doing that in 1981, so it’s 42 years of this, I’ll tell you,” she says. She’s done with “jumping from one subject to another constantly” and fighting with editors — who, she thinks, have just gotten worse. “I told my students — this is a regular piece of my advice — ‘If you’re at all given the choice when you step into a media arena of some kind, go with the oldest editor. The younger ones are going to be literal-minded. They’re going to be cops. They’re essentially narcs because they will rewrite your phrase that you carefully wrote so that people would actually have to read it. They will transform it into the cliché you were avoiding to begin with.’”

On the way to the train station, we drive into town to get pizza at Lola, where Sante always orders the same thing: the Fun Guy (ricotta, Fontina, mozzarella, local mushrooms; she adds figs). We eat at the counter in the window because Sante tells me that she refuses to wait for a table. The lemming scrum of competitive consumer behavior has never interested her. Sante, even freed up now to be a chattier and more easygoing version of herself, retains a bit of her aloofness. When I had asked Pinckney about whether Sante calls him on the phone now, he said, “No, no, no. I still have to call her. A star is born a star.”