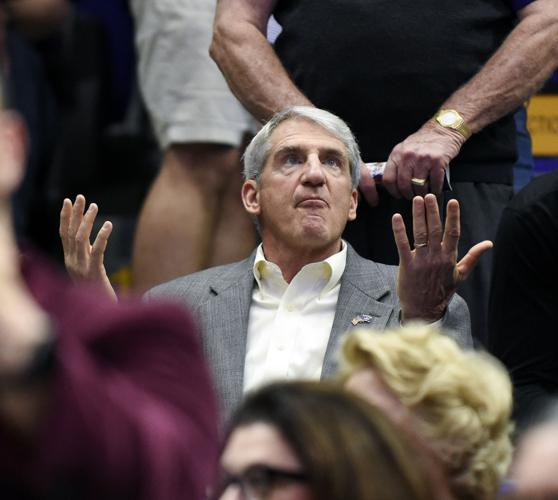

A chorus of boos rang down as Joe Alleva climbed the stairs in the Pete Maravich Assembly Center.

The jeers crescendoed as the athletic director slunk into a seat across from a “fire Alleva” banner.

It was March 2019, and the LSU Board of Supervisors was watching. The board’s discontent with Alleva had been building for years, and now there was blood in the water. LSU sports had been in a dry spell, though its men’s basketball team was making an impressive run. The controversy du jour stemmed from Alleva’s decision to sideline the coach, Will Wade, over alleged recruiting violations.

It was the perfect time to pounce.

LSU athletic director Joe Alleva reacts to being booed after walking into the arena to take his seat as LSU hosts Vanderbilt, Saturday, March 9, 2019, at LSU's Pete Maravich Assembly Center in Baton Rouge, La.

A few weeks later, four members of the board summoned LSU president F. King Alexander to the backroom of Juban’s Restaurant for what Alexander now refers to as the “Monday night massacre” and the “cocktail napkin incident.” He says then-LSU board chairman James Williams directed him to fire Alleva and to hire Scott Woodward in his place, writing down an eye-popping salary on a napkin.

Sitting with Williams were current LSU Board Chairman Robert Dampf, incoming LSU Board Chairman Remy Starns and former chairwoman Mary Werner, Alexander said. He was stunned and dismayed by the order, which he saw as well outside the board’s purview and a major violation of university policy and accreditation standards. But he followed their instructions and decided to start looking for a new job.

Starns took issue with Alexander’s account, saying the group had a broader discussion about problems with Alleva and LSU and that Alexander’s “entire characterization of what did or didn’t happen is flat-out wrong.” Williams has denied giving Alexander an ultimatum, though he confirmed he had discussed the job with Woodward ahead of time. Dampf and Werner did not return messages for this story.

The episode and its fallout illustrate some basic truths about the scandal over the mishandling of sexual assault and domestic violence allegations that has rocked Louisiana’s flagship university since late 2020.

Editor's note: This is a discrete chapter of a larger story about LSU's struggles to put a Title IX scandal behind the university and persuade…

One is that there’s overwhelming evidence some LSU Board of Supervisors members have prioritized athletic success above all else, though they insist they haven’t.

Alleva had recommended firing Les Miles years before his downfall after an investigation into allegations that Miles sexually harassed students. But Miles was succeeding on the field, and Alleva was ignored. And Alleva’s undoing was set in motion by his insistence on punishing the popular Wade over NCAA infractions, though LSU officials said at the time they wanted an athletic director with more fundraising prowess.

Another take-away is that, since the sex-abuse scandal broke a few months ago, LSU boosters, including the board, have implied or outright stated that they’ve already handled the personnel problems.

“They’re not our employees anymore, so we can’t discipline them, but they are responsible for some of the actions that took place,” LSU board member Randy Morris said during a recent board meeting.

Editor's note: This is a discrete chapter of a larger story about LSU's struggles to put a Title IX scandal behind the university and persuade…

Indeed, Miles, Alleva and Alexander are all long gone, but such claims conveniently overlook the reasons for their respective departures. Miles was fired because he was losing football games, not because he was allegedly harassing women. And Alleva and Alexander fell out of favor not because they were coddling wrongdoers — if anything, it was the other way around.

Alexander racked up enemies when he stopped all Greek Life activities in the wake of a student’s hazing death, and rocked the boat by using “holistic admissions” to increase diversity at LSU. Alleva incensed the fan base when he clamped down on Wade amid an ongoing FBI investigation, and he feuded with Miles when he insisted that LSU self-impose penalties during an NCAA recruiting investigation.

Miles was fired in 2016 when his clock management problems finally caught up with him and LSU lost a heartbreaker at Auburn. But very few people knew that, three years earlier, at least two students had accused him of sexual harassment, that he had entered a settlement with one, and that he had demanded the football recruiting office only hire blonde women with “big boobs,” as a former staffer now alleges in federal court filings.

Miles’ attorney has denied the allegations against him and accused the former staffer of “malicious and false” accusations.

Alexander left within a year of the napkin incident, and has since lost his new job at Oregon State University over his perceived failures at LSU. Miles met a similar fate at Kansas, while Alleva retired after getting the ax from Alexander.

Michael Martin has been in charge of universities across the country, but he says he’s only worked in one state where the governor has called …

But the four people who pushed Alexander to fire Alleva — and to promote Executive Deputy Athletic Director Verge Ausberry, who is squarely in the middle of the current scandal — are still leading the LSU Board of Supervisors.

It’s largely up to that group of board members to steer LSU out of the ditch, and they’ve made a show of cutting ties with LSU’s longtime law firm Taylor Porter and drawing up a resolution to condemn the past board members who handled the Miles investigation.

Alexander can’t believe what he’s seeing.

“The board leadership wants accountability and transparency now, and they're the ones who met me in the backroom of Juban’s,” Alexander said. “They’re trying to blame the Bobby Jindal (board members) for secrecy and the secrecy still continues.”

The Juban’s saga wasn’t the only unflattering story Alexander told about the board’s priorities: He recalled another time that Starns insisted a football championship would cure LSU’s woes — even after eight straight years of punishing budget cuts.

While LSU poured untold resources into the pursuit of national football championships, campus leaders for years ignored warnings that LSU did …

“Remy Starns slammed his hand down on the table and said that, ‘All of these things will take care of themselves if we win a national championship,’” Alexander said.

Starns called that account ridiculous and said he “wouldn't have done something like that.” He said any comments he’s made about LSU’s need to win stretch beyond football, adding he wants LSU to win “in the classroom, in the medical school, in the studio and growing crops.”

LSU, indeed, won the championship last year, but its problems hardly went away.

Much of what is now known about LSU’s failures came to light in the law firm Husch Blackwell’s review of LSU’s handling of cases of sexual assault and misconduct. The firm concluded LSU was running a deficient Title IX program, the federal law that requires institutions to investigate allegations of sexual misconduct and prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex.

Husch Blackwell found that it was hard to determine how LSU’s handling of the Miles case affected the climate of the Athletics Department, but “it certainly was not positive.”

Alexander argues that dethroned bigshots like him and Alleva are easy scapegoats. The culture of misconduct at LSU remains alive and well, Alexander says, and he can plausibly argue that he and Alleva were both punished for trying to address it. Alleva did not return a message for this story.

From left, LSU President F. King Alexander, athletic director Joe Alleva and Gov. John Bel Edwards speak before LSU's men's basketball game against Georgia, Tuesday, January 26, 2016, at the Pete Maravich Assembly Center.

“What speaks volumes in Baton Rouge — and I’m no Joe Alleva fan, by any stretch — but the fact that Will Wade is there and Joe Alleva is not, that’s all you have to say,” said David Ridpath, a sports management professor at Ohio University and past president of The Drake Group, an advocacy group that pushes for reform in college athletics.

Ironically, one reason Alexander lost popularity with faculty was that he fired a tenured professor who allegedly made frequent comments to her students about her sex life. In lawsuits that LSU eventually won, Alexander argued the university could not keep a faculty member who was committing major Title IX infractions.

Even amid scandal, 'the priority is football. Period.'

Despite the Husch Blackwell report’s explosive allegations, the power of LSU’s Athletic Department — and donors’ willingness to pony up big time money for winning coaches — has remained untouched. Athletics installed an associate athletic director for diversity, equity and inclusion; beefed up Title IX training; said they’ll make reporting lines clearer.

But football is still king at LSU.

The LSU Athletic Department spent nearly $149 million in 2019 — translating to $248,296 per student-athlete. That was 14 times the spending on the educational side, where $17,926 per student was spent.

The latest round of punishments for Ausberry, the executive deputy athletic director, also underscore football’s importance.

Contracts for new women's basketball coach Kim Mulkey and wide receiver coach Mickey Joseph were approved by the LSU Board of Supervisors athl…

Ausberry failed to report a 2018 text from an LSU football player who admitted hitting his girlfriend, yet Alexander said “the backroom four” ordered him to protect and promote Ausberry. They made that request even though LSU had been warned of Ausberry’s mistake, which led Alexander’s general counsel, Tom Skinner, to hire a Philadelphia law firm “to find out if athletics had done something wrong,” Alexander said.

Ausberry finally got a monthlong suspension after the Husch Blackwell report’s release. After some legislators demanded to know why more action wasn’t being taken against him, LSU announced Ausberry would be banned from attending in-person football games this year. He declined to comment for this story.

The new punishment “speaks volumes about the priorities of LSU’s administration and the Board of Supervisors,” said Michigan-based attorney Karen Truszkowski, who is representing a group of eight former students who say they were assaulted or sexually abused on LSU’s campus. “The priority is not deterrence and compliance. The priority is football. Period.”

“The focus needs to be on stopping this from happening again,” Truszkowski added. “Taking away football games doesn’t deter anyone. It only demonstrates that there is a long way to go for accountability. A very long way.”

Seven women who have come forward in recent months with stories about being sexually assaulted or beaten on LSU’s campus and then failed by ad…

The day Truszkowski filed her lawsuit, LSU introduced Kim Mulkey as the new women’s basketball coach. Mulkey is among the most successful women in college sports, and spent 21 years at Baylor, where she won three national titles. Many cheered her hire as a win for the other component of Title IX, which mandates gender equity in sports.

But Mulkey has drawn criticism for her comments about a sexual assault scandal that engulfed Baylor in 2017. Mulkey defended Baylor then, telling reporters to “find another story to write” because “the problems that we have at Baylor are no different than the problems at any other school in America.”

"If somebody's around you, and they ever say, 'I will never send my daughter to Baylor,' you knock them right in the face," Mulkey said. She apologized the next day, saying that she regretted her words and stressing that she sympathized with victims and was angry about how Baylor treated them.

Ridpath said that while hiring Mulkey was a home run from an athletic standpoint, the optics for LSU are not good.

LSU women's basketball head coach Kim Mulkey, left, addresses members of the Louisiana House of Representatives alongside House Speaker, Rep. Clay Schexnayder, R-Gonzales, Tuesday, May 4, 2021, at the State Capitol in Baton Rouge, La.

“For her to say those things at Baylor and then come to a place like LSU, what are you saying?” Ridpath said. “What are you saying to victims, what are you saying to others?”

LSU Athletic Department spokesman Cody Worsham declined to comment on Mulkey’s prior remarks, saying only that LSU feels “very comfortable with her as a leader and mentor of student athletes.”

Mulkey will earn $2.5 million in her first year, and $3.3 million by the end of the deal, meaning she’ll likely outearn Wade and most other male coaches at the school. Athletics has a separate budget than academics, as football generates its own revenue and Tiger Athletic Foundation donors help to pay for athletic projects.

But Mulkey’s big payday comes as the Athletic Department has warned about an $80 million revenue loss last year because of coronavirus-related cuts. TAF also announced last month that it would no longer put money toward academic scholarships and teaching awards this year because of the pandemic.

Attorneys for former LSU head football coach Les Miles held several discussions in 2013 about a settlement agreement with a student who accuse…

Asked about the high-dollar hire amid those gloomy numbers, Worsham said that Mulkey will be a transformational hire who can “have an impact across the entire state of Louisiana.”

“Like many of our peer institutions, the rising costs of competitive athletics along with the significant financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic has placed the department in a challenging financial position,” Worsham said. “However, we have a long-term plan to address these challenges while still investing in our programs, building up our reserves, and working annually to balance the budget.“

The Board of Supervisors also clearly hopes that its hiring of William Tate IV as president will prove transformational. The hire, announced Thursday evening, is a historic one: Tate will be the first Black leader of a school that didn’t accept Black students until 1953, and he is the first Black leader of any school in the football-mad Southeastern Conference.

But it’s also worth noting that Tate drew the attention of several board members when he came to Baton Rouge for a football game.

William F. Tate IV will be the first Black person to head LSU — the first to lead any Southeastern Conference college, for that matter — after…

Alexander sees the arms race among college sports programs as a major problem.

“Big-time athletics in the United States is out of control in spending, and nobody knows where it’s going to end up, but it’s not going to be good for the student athletes or for public education,” Alexander said.

While the Athletic Department used to boast of sharing the profits it generated with the academic side of campus, Woodward ended that policy in 2019, saying it was a “poor way to run a university” and that athletics needed all of its earnings to remain competitive. Alexander said he was never consulted about that change, and that he pushed back on it but LSU board members overruled him.

Worsham said the profit-sharing “was always intended as a temporary measure.”

LSU athletic director Joe Alleva, left, and LSU head coach Les Miles speak on the field during pregame warmups before kickoff against Auburn, Saturday, September 24, 2016 at Auburn University's Jordan-Hare Stadium, Pat Dye Field in Auburn, Al.

Meanwhile, the academic side of campus must cover Title IX’s mandates of Title IX to investigate sexual misconduct and domestic violence among all students — including athletes. Most of the plaintiffs in Truszkowski’s lawsuit are either athletes, women who worked in the LSU football recruiting department or women who say they were assaulted by athletes. The Husch Blackwell report said 10 football players in recent years were accused of rape or sexual misconduct.

Interim LSU President Tom Galligan has pledged to spend $1 million this year from the university’s academic budget — the most ever — to beef up Title IX offices and hiring staff. Neither the LSU Athletic Department, nor the Tiger Athletic Foundation, have offered to chip in. The Athletic Department generates well over $100 million in annual revenue.

'Does anybody believe you can do this kind of stuff and not have sanctions?'

In 2007, LSU faced another high-profile Athletic Department scandal. But it ended differently.

When LSU officials found evidence that former women’s basketball coach Pokey Chatman was having a sexual relationship with one of her players, her lawyer said the school gave her two hours to resign or to be fired.

DSC_0061 Advocate staff photo by Kerry Maloney. Photo shot on 2/27/05. LSU vs. Florida LSU head coach Pokey Chatman gets hoisted up by her players from left Sylvia Fowles and Crystal White after Saturday's win against Florida at the PMAC. Hanna Biernaka claps behind. The Lady Tigers won the SEC conference title outright for the first time ever.

Chatman’s attorney, Mary Olive Pierson, argued that LSU had no policy forbidding such a relationship. A similar argument has been used to better effect by those defending their actions in the current scandal: Galligan has said that LSU cannot fire employees if the policies obligating them to report misconduct were murky.

But that defense didn’t spare Chatman in 2007.

"Does anybody believe you can do this kind of stuff and not have sanctions?" Ray Lamonica, LSU’s general counsel, asked at the time. Lamonica also used general conduct clauses in NCAA bylaws and Chatman’s contract to defend LSU’s firing.

Reached for this story, Lamonica explained that LSU Board of Supervisors bylaws require that the entire board be apprised of “significant policy matters.” That meant that the full LSU board could have weighed in on Chatman if she hadn’t resigned — though years after Lamonica’s stint as general counsel, only a few board members were apprised of Miles’ sexual harassment allegations, in a potential violation of those bylaws.

When you look at the big picture of LSU’s football success this season, attention immediately turns to a couple of far-from-regular Joes: Heis…

“I did take the position that her firing could go to the Board of Supervisors if she didn’t resign, because it’s a significant policy matter,” Lamonica said.

Chatman walked away with a $160,000 settlement payout, and went on to coach professional teams. She declined to comment for this story. Pierson said the disparate treatment given to Chatman and Miles illustrates the formidable power of football on LSU’s campus.

“That’s where the difference comes in — we’re gonna defend that football coach until the cows come home; we’re not gonna defend Pokey Chatman and those girls out there shooting hoops,” Pierson said.

It’s hard to say how long it will take LSU officials to put the Husch Blackwell report in their rearview mirror. Two federal lawsuits have already been filed against the university, and LSU remains under two federal Department of Education investigations over crime reporting and Title IX compliance.

Five more women have come forward to speak out about unresolved sexual harassment complaints at the LSU medical school in Shreveport, offering…

Alleva and Alexander are unlikely to emerge unscathed in those investigations.

Alleva takes some blame in the Husch Blackwell report because he instructed employees to report Title IX complaints in-house to athletics, rather than to LSU’s Title IX office. Those directives contradicted orders from Alexander and LSU’s Title IX office.

Alexander, meanwhile, showed “a lack of effective leadership at the University with respect to Title IX,” Husch Blackwell found. Students, faculty members, staffers and others on campus told the firm that they blamed Alexander for failing to prioritize Title IX “or meaningfully engage with individuals raising concerns.” They found that while he’d commissioned a 2016 Title IX task force, its recommendations went nowhere, and that Alexander did not take urgent action on warnings from his own Title IX office or from Baton Rouge’s Sexual Trauma Awareness and Response Center.

Alexander says the task force provided a useful blueprint, and that he’s proud that he scraped together any funding at all to create a Title IX office when LSU was drawing up scenarios for a doomsday financial crisis.

Sexual assault survivors, university administrators, legislators, advocates and others spent a grueling 10 hours Wednesday at Louisiana's Capi…

But those concerns weren’t what chased him away from the stately oaks and broad magnolias. Leadership at Oregon State — where he was forced to resign over the LSU scandals — seemed to see Alexander as a football apologist who enabled abuse. Alexander sees himself differently, as a liberal who pushed LSU to be more inclusive and whose mother was a Title IX pioneer at the University of Florida.

He believes the problems at LSU will continue as long as board members, legislators and others prioritize football over all else.

As he noted wryly: “They never called me into a backroom behind Juban’s to remove a dean.”