Don’t trust me, I’m a Gazan doctor

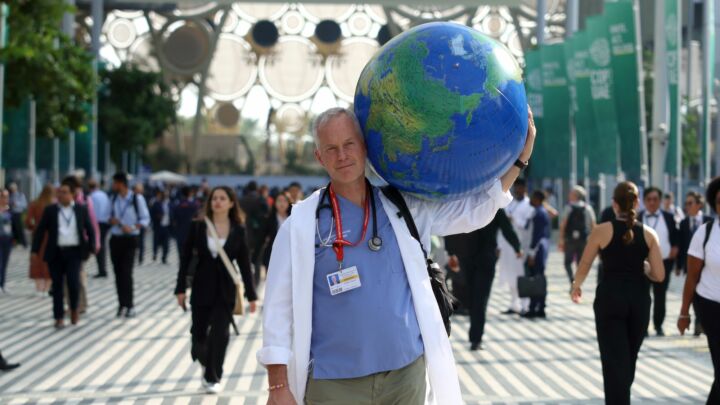

The media need to stop treating medics in war zones as fonts of truth.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In the Spring of 2005, when I was covering the Iraq War for Vanity Fair, I accompanied a squad of US Army soldiers visiting a sizeable hospital on the edge of the Sadr City area of Baghdad. An Iraqi doctor spotted my ‘press’ vest and took me aside. A handsome man in his late thirties, he spoke good English. He put his hand into the pocket of his white coat and took out a shiny .50-calibre machine-gun round. ‘These Americans’, he half-whispered, ‘two days ago they attacked our hospital! It is a war crime. You must report it.’

I might have photographed the heavy bullet and phoned home with my war-crime scoop, had I not been in the area two days earlier when the firefight he was referring to broke out. It had started when a joint US-Iraqi army patrol was fired upon from this very hospital. The ‘resistance’ had built firing positions in the hospital grounds, effectively using patients and staff as human shields and causing the hospital to lose much of its protected status under the laws of war. This genuine war crime was par for the course for all the Iraqi insurgent groups, both Sunni and Shia, as was the use of ‘Trojan ambulances’ to ferry fighters and explosives – a tactic also used by militants in Afghanistan and in the Israel-Palestine conflict.

However, the doctor in Sadr City made no mention of this misuse of his hospital. He was blithely confident that I would believe his claims about the US troops and their alleged atrocities. After all, he had dealt with my kind before. As a general rule, British journalists abroad never doubt the word of a doctor.

Indeed, from Yemen to Gaza, doctors are a preferred media source, believed without question. After all, they are university-educated professionals, wear Western-style clothes and usually speak English. I have seen British hacks, instinctively sceptical of anyone in a state-issued military uniform, become as credulous and undiscriminating as children when listening to a man or woman in a white coat wearing a concerned expression. They are seen as more credible, more worthy of trust than other people – a leftover, perhaps, from the class-ridden era in which a Brit who wanted a passport needed a signature from a doctor, lawyer or accountant.

This deference provides context for some of the media misreporting and mythmaking in the ongoing war in Gaza. The BBC and other mainstream news organisations seem only too happy to parrot the more outlandish casualty figures issued by the Hamas-run Gaza Ministry of Health and various accusations of Israeli war crimes made by unnamed ‘hospital staff’. The media also seem to rely on one medic in particular, Dr Ghassan Abu-Sittah, a surgeon whose social-media page is filled with posts sympathetic to Hamas’s 7 October attack. He has been quoted by every British outlet, from the Guardian to the Telegraph, as an impartial observer.

Deference to doctors is perhaps the more charitable explanation for the false report by Jeremy Bowen, the BBC’s international editor, in November 2023. He claimed that Gaza’s Al-Ahli hospital had been ‘flattened’ by a deadly Israeli airstrike. But, as soon became clear, the hospital was very much still standing, no one had been killed and the explosion in its parking area was the result of a misfired Hamas missile. When the same hospital was later captured by the Israel Defence Forces, soldiers found scores of Kalashnikov assault rifles and RPG rocket launchers inside. Bowen then bizarrely suggested that such weapons are a normal sight in Middle Eastern hospitals.

The unwillingness to scrutinise claims from healthcare workers in Gaza is deeply troubling. Under Hamas, Gaza is very much a one-party state, with a record of punishing perceived dissidence with severity. Its hospital directors are often military officers and many hospital staff are also members of Hamas’ military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades. That Gazan medics were involved in the mass kidnapping operation that accompanied the atrocities of 7 October has been confirmed by the recent revelation that some of the hostages recently rescued by the IDF were held at the house of prominent Gazan GP Ahmad Al-Jamal.

That doesn’t mean that every statement issued by Gaza’s health ministry, hospital administrators or doctors should be assumed to be propaganda. It just means that their statements should be treated like those given out or approved by the Assad regime in Syria, the Taliban in Afghanistan or the Kim government in Pyongyang – that is, with scepticism.

The ongoing inability of Western and especially British journalists to imagine that a doctor – a middle-class person like themselves, but with even more years in higher education – might also be a fanatic, a supporter of killers, or even a killer himself requires almost wilful ignorance. And not just of Second World War monsters like Nazi Germany’s Dr Mengele or serial killers like Harold Shipman. Recent history features doctor-dictators, such as Haiti’s ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad – a UK-educated ophthalmologist. Then there are the doctor-terrorists, like Ikuo Hayashi, who carried out the deadly Sarin Attack on Tokyo Subway; and, of course, Hamas co-founder and suicide-bombing innovator Abdel al-Rantisi.

Doctors have been almost as prominent in the jihadist world as engineers. Osama bin Laden’s successor as head of al-Qaeda was Ayman al-Zawahiri, a surgeon. The head of the viciously anti-Semitic Islamist group, Hizb ut-Tahrir, is the NHS’s own Dr Wahid Asif Shaida. Scores of physicians based in the UK, Pakistan and the US joined ISIS when the so-called caliphate was enslaving Yazidi girls and burning alive Jordanian pilots.

None of this should be shocking. Many who train to be doctors do so because they desire status and wealth, not because they are intrinsically benign, or devoted to the diminution of human suffering. They are as likely as any other profession to be drawn to political extremism, and perhaps more likely to have a stomach for the results of violence. The British media’s propensity to treat doctors as if they are priestly figures, presumptively above the fray of ordinary politics and prejudice is not just naïve and ignorant, it’s also dangerous to the truth.

Jonathan Foreman is a writer, editor and war correspondent. Follow him on X: @JonEForeman.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.