Long-read

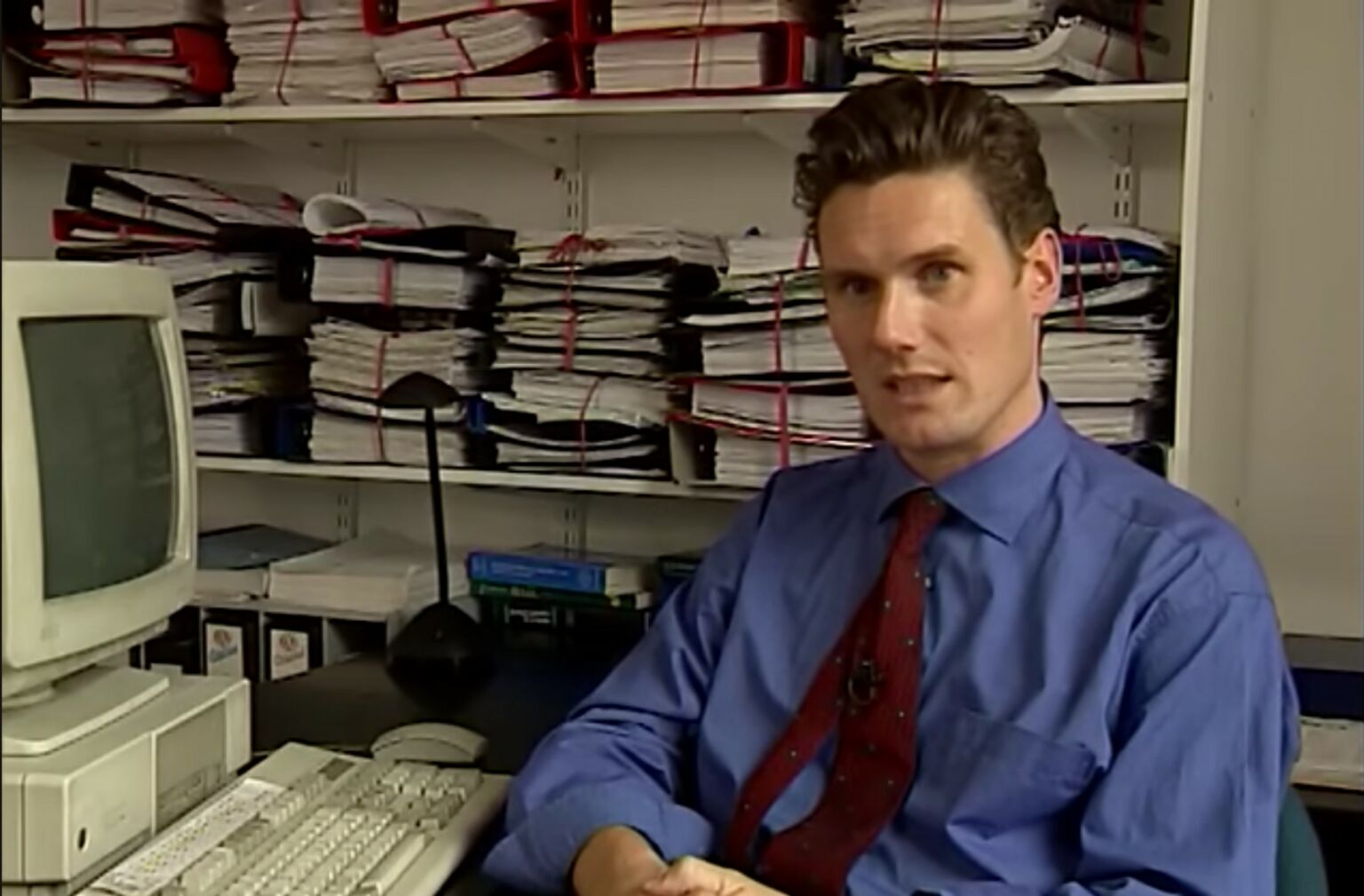

Keir Starmer: the making of an arch technocrat

The Labour leader is a creature of the managerial state.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Who is Keir Starmer? It’s the question that has launched a thousand comment pieces over the past few years, as pundits scrabble around trying to work out what exactly the Labour leader and presumed next UK prime minister stands for.

Well might they ask, too. As Tom Slater has explained on spiked, this is a politician who has shredded virtually every principle he professed to hold dear and broken almost every policy promise he has ever made. He is a u-turning machine, a master of the reverse ferret. Pledges made to Labour members in 2020 to nationalise public services or abolish tuition fees were unceremoniously dropped a couple of years later. Talk of raising income tax for top earners has been replaced by a commitment not to implement tax rises.

Trying to work out who Starmer is, and above all what it is he stands for, is like trying to catch smoke. There is no ideology, no guiding principles, no real vision. Nothing specific he wants to achieve.

Some have compared him with Tony Blair. But for all the sins and managerialism of New Labour, it at least had a sense of mission to it. Blair and his acolytes set about remaking Britain, in the image of technocracy and multiculturalism, with a certain zealotry. Starmer and Starmerism have no such philosophical grounding or sense of mission.

Journalists Gabriel Pogrund and Kevin Maguire claim that Starmer has an ‘inchoate moral compulsion’ rather than a ‘fully formed worldview’. Starmer himself told Paul Mason in 2020 that he wanted to be Labour leader because, ‘if I see something wrong in society… I’ve got to do something about it’. This, it seems, is how Starmer conceives of politics, as the act of getting things done, of solving problems. In a speech attempting to outline his party’s ‘national missions’ last February, he declared: ‘Things that could be sped up, joined up, given direction, made to work better. This is at the core of my politics.’

Which is a pretty dull core. Starmer is less a politician than a project manager. He talks in terms of competence, coordination and efficiency. Of how things get done. Of means. But he seems far less concerned with what gets done, with the ends of action. He appears to be all process and little purpose. Where is the substance beyond some vague, arbitrary ‘moral compulsion’? What is the point of Starmer?

Starmer and his aides are clearly aware of the questions being asked of who exactly he is and what he stands for. So in recent years, they have been keenly offering up a ready-made answer in the shape of the Starmer backstory. We’ve been told over and over again that his dad was a toolmaker and his mum was a nurse. That he grew up in a pebble-dashed semi. That he enjoyed a far from privileged early life. The Starmer backstory even played a central role in his first General Election speech last month. The backstory’s purpose is simple. It attempts to establish some sense of Starmer in the public mind as a man from a working-class background. A man who understands the trials and tribulations of ordinary Brits. Someone decent, authentic and on your side.

Born in 1962, Starmer grew up in a small village near Oxted in Surrey. His dad was indeed a toolmaker, working at local factories before starting his own tool-making business (albeit as a sole trader), hence more recent accusations that the Labour leader is not as proletarian as has been suggested. Starmer has talked movingly of his relationship with his parents, describing his dad as ‘a difficult [and] complicated man’. This was partly because he dedicated much of his life to looking after his wife, Jo, Starmer’s mum. As a teenager, she had been diagnosed with Still’s disease, a rare autoimmune condition, which caused rheumatoid arthritis and left her vulnerable to injury and infection – she even had to have her leg amputated in later life.

Starmer has also been keen to tell us that his parents were Labour to the core, so much so that they named him after Keir Hardie, the party’s first leader. According to one biographer, that infamous ‘pebble-dashed semi’ was often decorated with Labour’s red and gold posters and placards pledging support to striking miners and firemen. We’re told that Starmer himself inherited his parents’ Labourism. Catching the bus to Reigate grammar school, he and schoolfriend Andrew Sullivan, now a successful conservative writer in the US, used to engage in loud political arguments on the top deck.

The backstory is vaguely interesting. The fact that Starmer, a talented musician, went for violin lessons with a young Norman Cook, better known as Fatboy Slim, is certainly one for the pub quiz. But to really understand what and who Starmer is as a politician, we have to look beyond all this. Beyond the legend of the left-wing toolmaker’s son made good. Beyond, that is, the story Starmer and Labour want to tell. We need to look instead at Starmer’s intellectual and professional coming of age as a young law student and then barrister. At how he then flourished amid the enthusiasm for human-rights law and a rules-based international order that so enamoured our post-Cold War elites during the 1990s. What emerges is a creature of the regulatory, technocratic state. A man who elevates experts over the demos, who privileges rules over decisions, procedure over principle. A technocratic legalist concerned more with how to get things done than what gets done.

Too often, media portraits of Starmer miss all this. Right-wing commentaries especially draw attention to his youthful radicalism, often as part of an effort to portray him as a Marxist in centre-left clothing. They eagerly draw attention to both his membership of the left-wing Labour club as a law student at the University of Leeds in the early 1980s and, above all, to his joining the editorial collective of the far-left Socialist Alternatives magazine, after completing a one-year civil-law course at the University of Oxford in 1986.

These years were certainly important in the formation of Starmer’s outlook. But not in the way that is commonly thought. His study of law, and subsequent legal career, have been far more influential in shaping his instincts.

The broader context is all important here. In the 1980s, the organised working class suffered a series of setbacks, culminating in Margaret Thatcher’s crushing of the Miners’ Strike in 1985. This defeat quickened the intellectual decay of large parts of the left, as many of its middle-class adherents abandoned class politics in favour of the then shiny ‘new social movements’, from feminism to environmentalism.

Starmer didn’t contribute much editorially to Socialist Alternatives. The few pieces that he did write show someone less interested in the fundamental economic re-organisation of society, or in the agency of the working class, than in an incipient identity politics. He couched this in the terms of a ‘red-green’ alliance between the struggling labour movement and what he saw as ‘progressive’ movements. Starmer’s political views, such as they were, reflected the broader intellectual decomposition of the left during the 1980s, and its withdrawal from the working class.

Far more significant was Starmer’s growing enthusiasm, from the 1980s onwards, for international and human-rights law, especially the European Convention on Human Rights. As he puts it himself: ‘[Human-rights law] gave me a method, a structure and framework, by which I could test propositions, and it brought politics into the law for me.’

‘[Human rights] brought politics into the law for me.’ This is a telling reflection. It captures the way in which Starmer, from very early on, saw human-rights law as a form of political activism. It suggested to him how the law could be used not just to defend individuals from state power, but also how it could be used to regulate and order society according to the wishes of those who supposedly know best.

He carried these ideas into his pupilage at a relatively liberal set of barristers’ chambers in 1987. Four years later, Starmer was one of 30 and soon-to-be very influential left-leaning barristers to move out of their traditional home in the Temple – a ‘sclerotic caste-based institution’, as their leader Geoffrey Robertson put it – and into an office on Doughty Street in Bloomsbury. Over the following 15 years or so, Starmer made a name for himself as a defender of countless good, liberal causes, from the 15-year-long McLibel trial to pro-bono work on death-penalty cases in the Caribbean and East Africa.

At Doughty Street, Starmer increasingly conceived of human-rights law in particular as a way of getting things done, driven by the experts of the judiciary. In 1995, as talk of a potential Labour government introducing a human-rights act intensified, he argued in the Socialist Lawyer that ‘the entrenchment of fundamental rights [is capable of] contributing to the realisation of progressive change’. He said that human-rights legislation could be used as an instrument to improve the lives of ‘all those burdened with poverty, oppression and exploitation in Britain today’.

Helping the impoverished and oppressed are admirable ends. The problem was that Starmer was promising to do so through legal activism, from up on high, through carefully wrought articles and clauses. His developing technocratic worldview rested on the anti-democratic assumption that law and its expert practitioners are better placed to make decisions about society than the public or its elected representatives.

By this point in the mid-1990s, amid talk of the end of history and the new liberal world order, Starmer was singing from the same hymn sheet as much of the liberal left. With New Labour’s election victory in 1997 and the passing of the Human Rights Act (HRA) the following year, Starmer’s brand of technocratic legalism was in the ascendancy. He later praised the HRA for ‘giving dynamic effect to human rights’, making ‘them practical and effective’. The HRA, a technocrats’ charter, confirmed him in his belief that the law, active and expanding, really could start to help get things done. In his mind, procedural legal thinking displaced politics.

It should be said that Starmer was not a New Labour sycophant. In 2003, he came out against the invasion of Iraq in a piece in the Guardian. Tellingly, however, Starmer’s objections were entirely legalistic, focussing on what international legal resolutions and articles authorise and what they do not. His objection to the invasion of a sovereign nation wasn’t political or moral. It was procedural.

Starmer’s public criticism of the Labour government didn’t do him any harm. In 2008, prime minister Gordon Brown appointed Starmer as director of public prosecutions (DPP). Some of his leftist critics have seen this move on Starmer’s part as a betrayal. A sign of his growing authoritarian leanings. As fellow left-wing barrister David Renton explains, Starmer was seen as ‘a principled opponent of state power’. Now he was an executor of state power, ‘prosecuting defendants so that they are fined or jailed’.

But heading up the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) wasn’t a testament to Starmer’s authoritarianism, so much as his legalism. He never had a burning passion for civil liberties or for limiting state power over the individual. He had a passion for process and legal bureaucracy. He was concerned with establishing an efficient, competent framework for governing and changing society. At the CPS, exercising state power according to the rules, he found his natural technocratic home.

As DPP he was involved in plenty of controversial cases, including the mooted extradition of Julian Assange to the United States. A few of his actions are worth drawing particular attention to: his determination to prosecute journalists involved in the ‘phone-hacking’ scandal; his development of prosecution guidelines to make it easier for the CPS to prosecute peaceful protesters; and his advocacy of the so-called snooper’s charter, which gave the state access to citizens’ private data. These are the moves of someone with little to no regard for democratic freedoms, from that of the press to those of citizens. For Starmer, people’s liberties are a problem to be managed according to expert-authored rules and procedures.

Starmer’s role at the head of the CPS tells us something else, too. His technocratic legalism was certainly forged during the 1980s and the rise of human-rights law during the 1990s. But it was honed through his immersion in the British state itself. He may talk today of himself as a political outsider, as a late-comer to Westminster. But that’s pure PR. He spent five years working alongside the government, exercising the state’s prosecutorial powers. He is of the state and for the state.

From when he became Labour MP for Holborn and St Pancras in 2015, to his appointment to the shadow cabinet under Jeremy Corbyn, to his rise to the Labour leadership, he has conducted himself as an arch technocrat. As he told one biographer, he entered Westminster to ‘pull levers only politicians could do’, to put himself in a position to ‘make social justice’. He didn’t talk of his constituents, of representing their interests, or any of the other stuff usually associated with parliamentary democracy. For Starmer, it’s all about those who know best manufacturing ‘social justice’. Quite what this means remains unclear. What is certain is that the public will have little say on it.

This technocratic legalism fuelled Starmer’s enthusiasm for expert-driven lockdown rules during the pandemic. It is writ large in Labour’s draft policy platform from 2023, in which he calls for moving ‘decision-making away from Westminster to those with the experience, knowledge and expertise’. And it certainly lies at the root of his support for the European Union, an institution dedicated to insulating decision-making from national electorates. This drove him to try to thwart Brexit at every opportunity, obstructing it in parliament as shadow Brexit secretary and conniving against it through his work with the People’s Vote campaign. He was one of the driving forces behind Labour’s decision to call for a second referendum and campaign for Remain.

But perhaps the most telling illustration of Starmer’s outlook arrived at the beginning of last year during an interview on the News Agents podcast. He was asked whether he preferred Westminster or Davos, the home of the World Economic Forum. ‘Davos’, he said, barely pausing. He complained that Westminster is just full of talking and conflict (otherwise known as political argument), whereas Davos, populated by businessmen, politicians and NGOs, is a place where things get done.

This is the real Keir Starmer. A figure forged in the heart of the legal, technocratic establishment. A man far more comfortable among those who wield power at the WEF than among those answerable to voters. To the extent that he stands for anything, he stands, instinctually, for rule by experts, lawyers and state functionaries, unencumbered by democracy. For an unaccountable elite, and against the people.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Melanie Phillips and Brendan O’Neill – live and in conversation

Wednesday 26 June – 8pm to 9pm BST

This is a free event, exclusively for spiked supporters.

Pictures by: Getty Images.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.