Long-read

How safetyism fuelled the Gaza campus protests

Infantilised students are lashing out at a Western civilisation they have been taught to loathe.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The phrase ‘student protest’ fails to capture what is distinct about today’s pro-Palestine campus demonstrations.

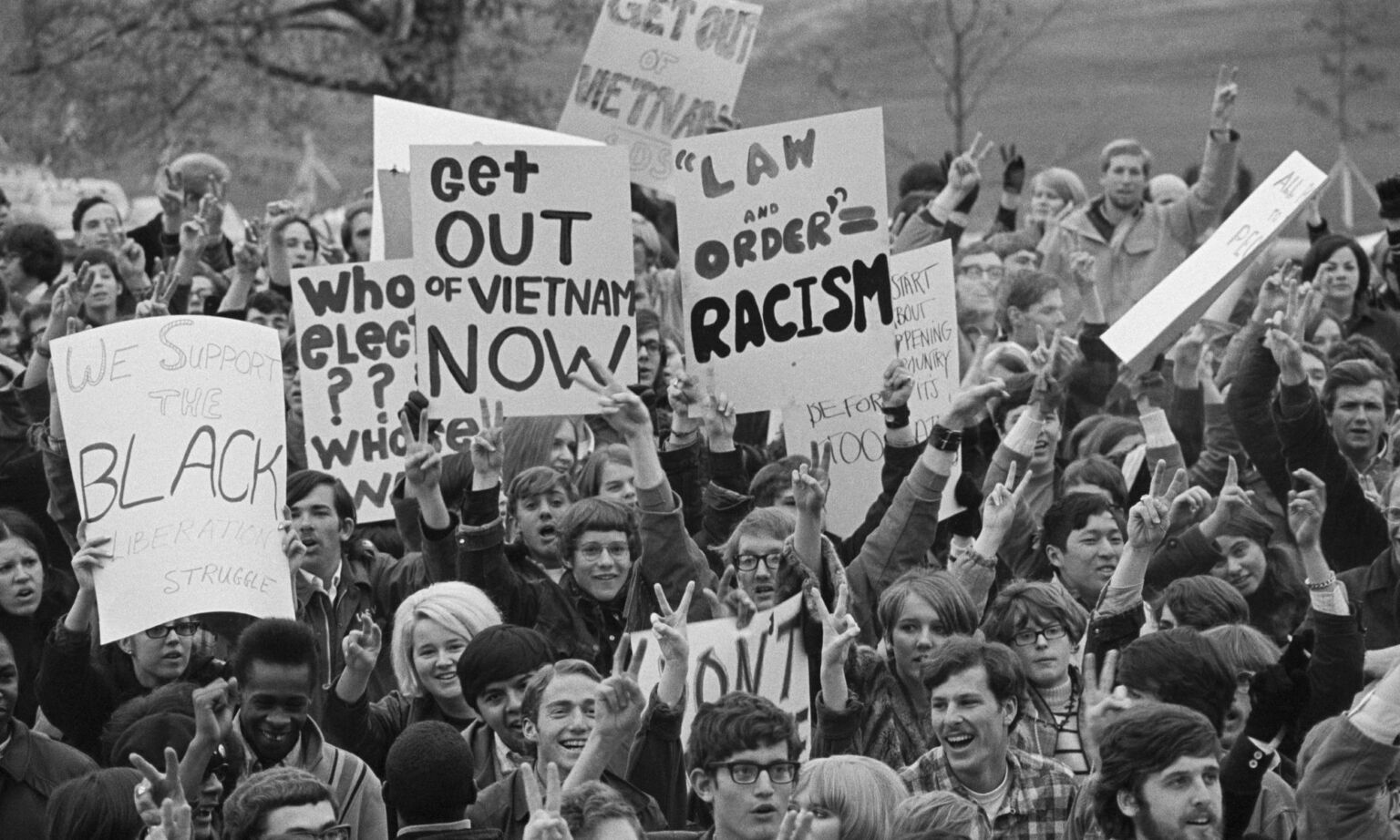

Too many commentators are portraying the current wave of campus protests against Israel as merely the latest manifestation of a long tradition of youthful rebellion dating back to the 1960s and 1970s. Indeed, many have explicitly compared today’s protests with the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations. According to the New York Times, the campus protests over Gaza ‘echo’ the historical ‘outcry over Vietnam’. For Time magazine, they’re part of ‘a long-standing American tradition of non-violent civil disobedience’, stretching back to the ‘anti-Vietnam War protests’ and beyond.

In some instances, the parallels being drawn between these two very different historical events verge on the bizarre. ‘Israel’s war on Gaza now resembles our war on Vietnam’, asserts an essay in the American Prospect. This overlooks the fact that, unlike Hamas and Israel, the Vietcong never invaded America, caused mass American casualties or called for the destruction of America. It also fails to note that the pro-Hamas protesters are not anti-war – they actually support the destruction of the state of Israel.

The numerous attempts at drawing connections between past demonstrations over Vietnam and today’s demonstrations over Palestine overlook their specific, respective features. They fail to take into account the strikingly different cultural norms that influenced the earlier protesters’ attitudes and behaviour. They had very different motives, and very different relationships with the dominant institutions and classes of society.

In nearly every respect, the universities, academics and students of the 1960s are very different to those of today. Crucially, the student movement of the 1960s directly challenged the prevailing cultural norms. In inspiration and aspiration, it was counter-cultural. It called into question the dominant values and norms of its society.

In contrast, the current anti-Israel movement, in outlook and attitude, is not opposed to the prevailing cultural norms. It merely represents a more radical version of the attitudes shared by the dominant cultural institutions of the Anglo-American world. Contemporary students’ animosity towards Israel is merely the more youthful and unedited version of the more carefully expressed sentiments of our cultural elites. This was clear at December’s Congressional hearings into anti-Semitism on campus, when the heads of Ivy League universities seemed unwilling to condemn the hatred towards the Jewish State on display from their own students.

It’s clear that higher education has changed markedly since the 1960s. With more and more young people now attending university, higher education has become increasingly commodified and industrialised. Numerous commentators have noted that the ‘massification’ and ‘marketisation’ of higher education has led to undergraduates being treated more like customers than scholars. As customers, students are flattered rather than challenged. Far less work is now expected of them and academic life has been rebranded as the ‘university experience’ or ‘student experience’. The job of higher-education managers is merely to ensure the customer satisfaction of undergraduates.

In the 1960s, students rebelled against and eventually overturned the in loco parentis responsibilities universities held over them. After that, students were expected to more or less fend for themselves. In contrast, students today demand to be treated as quasi-children. In response, universities highlight their commitment to student welfare, offering extensive pastoral care, counselling and guidance. They effectively promise parents that they will keep their kids safe.

Indeed, safety is now a foundational value on campus (and beyond). Administrators and academics, often at students’ behest, put ‘trigger warnings’ on books deemed to be potentially upsetting. ‘Safe spaces’ for particular identity groups of students have proliferated. University authorities now play the role of paternalistic guardians of student welfare.

All of this has transformed the relationship between academics and students. In the past, academics would take an interest in the lives of their students, but they didn’t play the role of amateur therapists or proxy parents. What’s more, most students would have resented attempts by campus authorities and academics to intrude into their personal lives. They wanted the freedom to conduct their private affairs as they saw fit.

This began to change as early as the 1980s. Academic institutions began to treat students as not quite capable of exercising the responsibilities associated with young adulthood. This shift from an open to a regulated campus was often justified in the language of risk and harm. Strikingly, there was no significant opposition to this from students and academics. By the mid-1990s, students’ unions in the UK were in the forefront of raising ‘awareness’ of health and wellbeing issues.

The contrast between campus culture in the 1960s and now is stark. The 1960s campus was a parent-free zone. Today, institutions of higher education organise open days for parents (and students) and target them with advertising literature. In turn, many parents take it upon themselves to exercise a degree of surveillance over the progress of their children when they start university. Many expect the university to operate like a school and exercise a ‘duty of care’ for their children.

In this respect, the pre-existing distinction between a high-school pupil and an undergraduate has eroded. The contemporary undergraduate tends to be regarded as a biologically mature child – a vulnerable young person whose safety must be protected through institutional support and intervention.

This infantilisation is arguably the most dramatic change on campus over the past five decades. There are of course many students who resist being treated like children. Nevertheless, the infantilising ethos dominates. Instead of encouraging students’ moral and intellectual independence, universities cultivate their sense of vulnerability.

This infantilisation is founded on a diminished view of human subjectivity. Individuals are regarded not as agents, but as the potential victims of circumstance. As many observers have noted, these sentiments are widely held throughout society. However, paternalistic etiquette truly dominates on campus. Outwardly, this etiquette appears to encourage non-judgementalism and open-mindedness. ‘Be Kind’, etc. However, in practice, it encourages authoritarianism and intolerance – and even violence – towards ideas and forms of behaviour that violate its norms. Universities and their students endorse the value of diversity but refuse to tolerate a diversity of opinions. Violent intolerance is the flipside of rampant safetyism.

The infantilisation of students – the assumption of their fragility and vulnerability – has gone hand in hand with the institutionalisation of what I have characterised elsewhere as therapy culture. The most tragic consequence of the therapeutic turn in higher education is the normalisation of mental illness. Virtually every existential problem confronting students today is reframed in terms of a psychological disorder, syndrome or condition. This is partially responsible for what’s often referred to as the campus ‘mental-health crisis’.

These twin trends – infantilisation and therapy culture – have created a environment in which students are regarded as children who must be insulated from adversity, pressure and criticism. Trigger warnings are merely one part of a widespread policing of speech designed to ensure students are protected from offence and trauma. Students have embraced this therapeutic worldview. As a result, they see freedom from offence as their right and vigorously support the policing of language. That is why the slightest hint that a text is offensive frequently prompts an outraged response from students. The therapeutic transformation of campuses has fuelled a new conformism, and undermined freedom of speech.

Again, the contrast is stark. In the 1960s, students fought for free speech and academic freedom. Debates were serious and could be fierce. Few participants paid any attention to whether or not someone was offended by the words directed at them.

The war in Vietnam was especially hotly debated. At meetings, determined advocates of the war clashed with those who opposed it. During anti-war occupations, arguments over tactics and strategy often broke out even among those on the same side. This was an era when you were not at risk of cancellation for holding a minority view. It was even possible for students to have friends from different sides of the political divide.

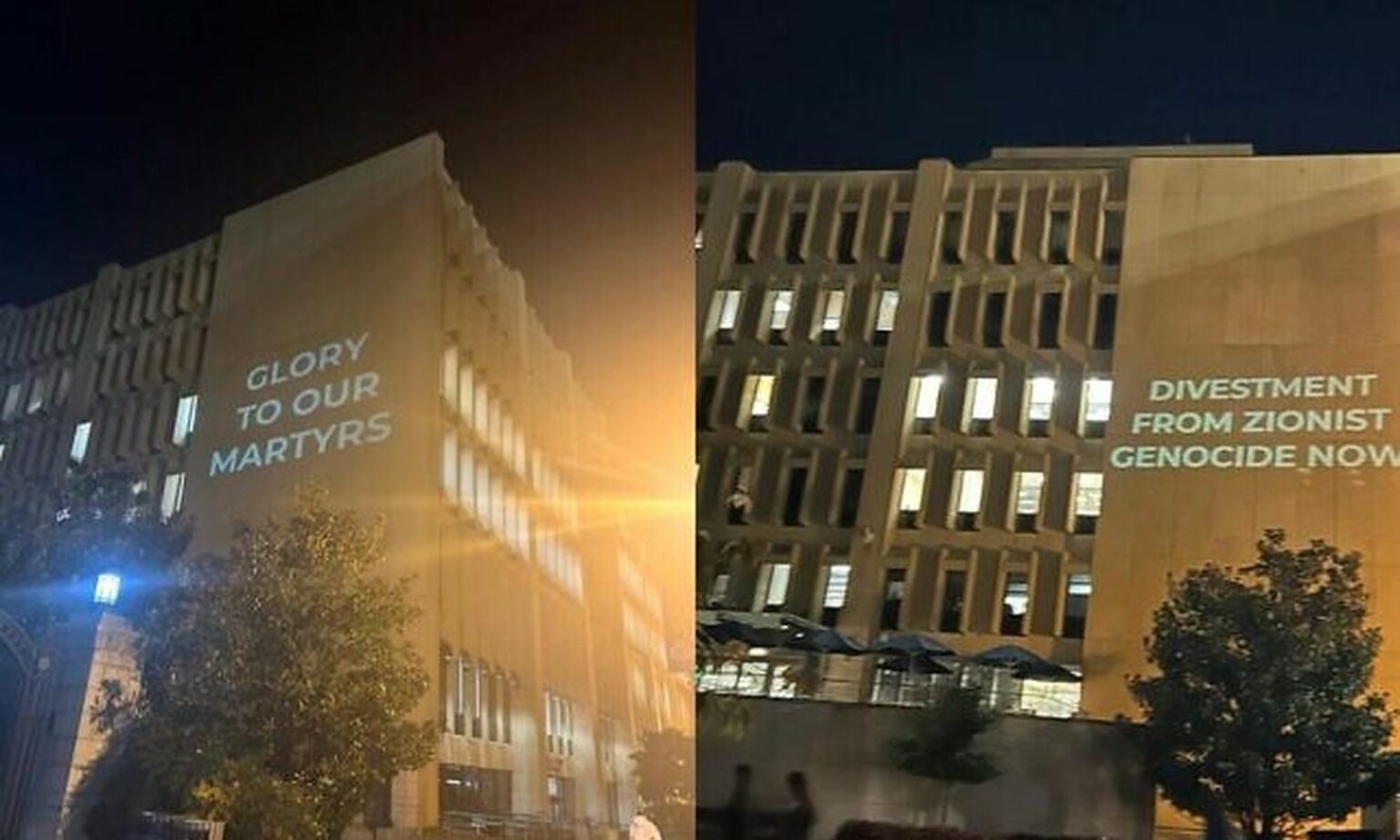

Today, however, campus is intensely polarised. The idea of free speech has lost its authority and debate is often ruled out as too risky. This is particularly apparent in the case of the anti-Israel demos. Those students who are committed to demonising Israel are not prepared to argue with their opponents. They don’t even pretend that debate is valuable in its own right. Believing that the expression of a divergent view is offensive and its communication a cultural crime, they only want to denounce and silence their opponents.

There is a third element that is shaping today’s student protests – namely, their anti-Western identitarianism. This standpoint, itself shot through with a therapeutic narrative of victimisation, is most systematically expressed in the popular narrative of ‘decolonisation’. Decolonisation means many things today, but above all it involves negating the legacy of Western civilisation and promoting a quasi-religious sense of guilt about benefitting from it. As a result, all acts committed by those who perceive themselves as colonised are not only understandable but also justifiable. So, ever since Hamas’s pogrom in Israel on 7 October, numerous pro-Hamas academics have gone to great lengths to make excuses for the atrocity, to present rape and murder as a form of resistance. They have taken to social media to point out that ‘decolonisation is not a metaphor’ and to revel in the violence that Hamas has inflicted on Jewish civilians.

The crusade against ‘whiteness’ is also important in this context. It explains why various identitarian groups are now spontaneously lining up with Hamas to oppose Israel. For these identitarians, Israel is a proxy for whiteness and Western civilisation as a whole. Hence it has become such an object of hatred.

Students’ embrace of anti-Westernism is hardly spontaneous. Western society is demonised throughout the university curriculum. In that regard, support for an enemy of the West such as Hamas conforms to the prevailing campus zeitgeist. This is why many students who are indifferent to the situation in the Middle East, or are opposed to the cause of Hamas, are likely to keep their opinions to themselves. They find themselves in a minority, set against fellow students and academics.

The infantilised and conformist sensibility among the protesters is manifest in the ubiquity of the keffiyeh. For many white students, the act of wearing this scarf (often paired with a mask) serves as a ritual of purification. By joining the crowd and chanting ‘From the river to the sea’, they hope to wash away the guilt of whiteness.

Many protesters are not motivated by the plight of the Gazan people. They are driven instead by the desire to conform to the infantilised, anti-Western culture they see around them. Once the current pro-Palestine movement exhausts itself, this new generation of activists will no doubt move on to support the next anti-Western movement.

The student protesters of the 1960s may have been very different in their motives and character to today’s infantilised protesters. But there is a reason why so many of them have spoken out in support of the campus protests. They recognise themselves in the keffiyeh-sporting crowds. The 1960s students, as stated, were certainly counter-cultural and challenged the dominant norms of society. But in the decades since, they and their progeny have captured the very cultural institutions, from the media to the university, they once opposed. Meanwhile, their original anti-imperialism has degraded into a form of empty, intolerant anti-Westernism.

This opposition to the West, to its historical and cultural inheritance, has become the default position of the elites. When you watch today’s anti-Western foot-soldiers casually vandalising things on campus, as happened at Amsterdam University this week, their anti-civilisational impulse becomes all too clear. Their mindless use of violent and authoritarian tactics may serve a therapeutic purpose. It may make them feel good about themselves. Perhaps even purified. But it represents a serious challenge to the integrity of a democratic way of life.

Frank Furedi is the executive director of the think-tank, MCC-Brussels.

Pictures by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.