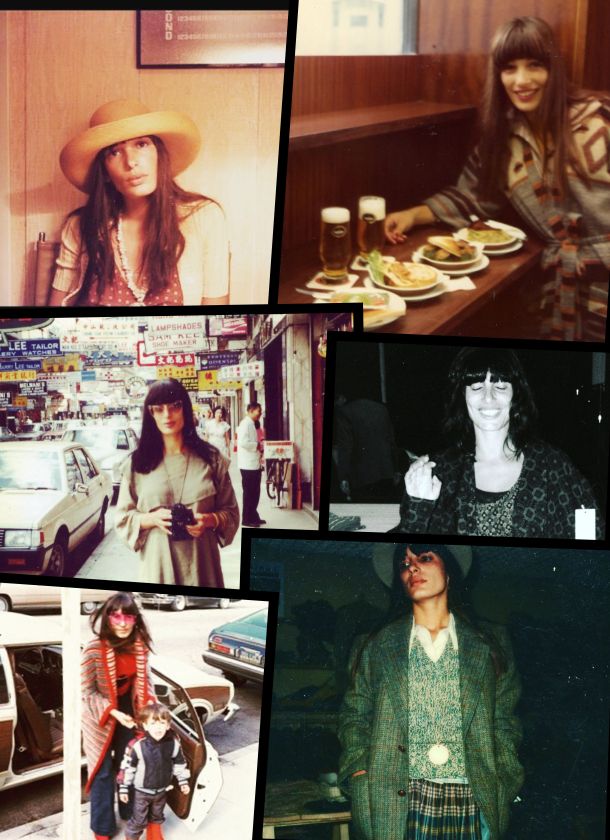

The Style Series: Madeleine Gallay

Crédits photo : Madeleine's private Instagram

“It was a fantasy world, like stepping into the pages of Vogue magazine,” Madeleine Gallay recalls of the moment she first set foot in Charles Gallay’s original Hollywood boutique in the 1960s. In a short time, the Angeleno retailer would become her partner — both in life and business. Together, the couple introduced Karl Lagerfeld’s Chloé to L.A., tracked down Yohji Yamamoto in a Japanese warehouse, and — with the help of Andrée Putman — opened Azzedine Alaïa’s first store in the U.S.

Nearly two decades later, in 1988, Madeleine struck out on her own with a seminal pink-walled shop on Sunset Boulevard, complete with Manolo Blahnik heels, John Galliano bias-cut dresses, and custom fantasy hats by Mary McDonald. “I was always in it, frankly, for the clothes,” she now says. “I loved the clothes, and I loved buying them.”

Below, Madeleine looks back on her days at the vanguard of fashion.

How did you get into fashion?

I suppose from being a little girl wandering into my mother’s closet and slipping on high heels and a silk dress… It was just a natural progression. I always loved clothing and fashion. One day, in the ’60s, I walked barefoot, which is embarrassing—I had just broken a sandal—into what would be my future husband’s shop [Charles Gallay]. It was a fantasy world, like stepping into the pages of Vogue magazine, with Halston and Sonia Rykiel… And then it began.

You opened your first boutique, on Camden Drive in Beverly Hills, in 1971…

It was a very bizarre time, but it was an incredible time. The store began in West Hollywood in the late ’60s; after a robbery in that location, the Tiffany shop in Beverly Hills became available, and we opened that store in ’71. The beginnings were kind of awkward. The buying trips were very hard and could last weeks since you had to get to Milan and Florence and there was no organization yet. No one allowed pictures to be taken—until suddenly it was acceptable so many decades later. We were carrying Missoni, which was at the Pitti Palace back then. At that point, you had to buy some Krizia in order to buy Missoni, but the next season we were able to go to Sumirago to buy Missoni… Didier Grumbach had this tremendous factory that was producing Saint Laurent, but he also was young and excited about fashion, as he was his whole life. He formed a group to produce Issey Miyake, Ossie Clark, and Emmanuelle Khanh, and the clothes were absolutely amazing. Andrée Putman opened a small showroom, Créateurs & Industriels, in Paris with these things.

What designers were you carrying at that time?

We brought Alaïa into our boutique, and we were buying Karl Lagerfeld’s Chloé, which was exquisite back then. It was a time before there were one-designer shops in Beverly Hills. We had Fendi and Bottega Veneta bags for one or two seasons before they opened a shop. We also had Missoni, Gaultier, Kenzo, André Laug, Gianfranco Ferré, Steven Sprouse, Jean Muir, Thea Porter, Walter Albini… We even added a space for Armani men’s. We had everything.

In ’73 or ’74, we had a Zandra [Rhodes] show at Mr. Chow that was so successful that we had to have two. Zandra was staying at our house, and I wouldn’t let her use our towels because she had pink eye, so I had to buy new towels just for her. She was amazing; she would iron all the clothes for the show herself. God, it was fun back then. It was the beginning, so even if somebody was quite wealthy, like Karl Largerfeld, they were still starving to build their business. Armani was designing for maybe 12 companies in Italy; he didn’t have money to be the gracious Armani that he became. Versace, the same. Walter Albini was the superstar stuck on heroin in Venice. It’s rumored that the only reason that designers have their name on labels is because he insisted on that for a company called Trell. Walter Albini for Trell. I don’t know if that’s true or not.

The designers, at the beginning, were more delighted to have the very cool boutiques pick up their collections rather than the department stores, which were perceived back then—except for Bloomingdale’s and Geraldine Stutz’s Bendel’s—as older and more staid. That changed very quickly, of course, because they had the big bucks, and they were suddenly aware that there was huge money in what were essentially groovy street clothes.

You also carried Japanese designers who were then largely unknown in the U.S…

The story of how Japanese clothing came to be in the U.S. is not well-known. It wasn’t [due to] the cool fashion boutiques but rather to Faye Dunaway and her then husband Terry O’Neill, who had a small shop in Santa Monica carrying the Japanese designer Yoshie Inaba. The clothes were fabulous, street-chic, and perfect—except that they were in Japanese sizing, which was so wrong for the tall, slim American girl. That was what sent us off to Japan in the ’70s, where we found Yohji [Yamamoto] and Rei [Kawakubo]. Yohji had a huge warehouse, which looked like an old-school auto garage, but he wasn’t yet ready to add Western sizes—nor was Rei, until she came to Paris in 1981 to show in the basement of the George V.

You were known for being one of the only American retailers to carry Alaïa and then opened the only all-Alaïa store in the U.S. How did you discover him?

Hebe Dorsey of The International Herald Tribune was pretty much the most important fashion writer when the buyers were in Europe. She had an unspecific paragraph or two about a designer that the women in Paris were flocking to. It was not completely mysterious because we did land there, but there weren’t pictures. We were just there on a treasure hunt, and it was a safari to find things… We went to rue de Bellechasse [Alaïa’s first atelier]; it was just an apartment that was extraordinarily busy. Much to our chagrin, Fred Hayman [who owned the boutique Giorgio Beverly Hills] was sitting there writing an order. The clothes were what we did, not what he did. He was more va-va-voom and a little more flashy, and we were still the equivalent of urban art, so to speak. We knew we needed the clothes, and we simply explained that. It was stunning: they asked Fred to leave. Fred was a great retailer, but they let us have the clothes. We couldn’t get enough. We just kept ordering for our Camden Drive store and going to Italy to work with Silvia Bocchese’s factory, which produced Alaïa’s knits. In ’83, [the footwear designer] Donald Pliner was giving up his shop on Rodeo Drive, so we took it over for Alaïa.

What was the Alaïa boutique like?

It was quite extraordinary. Azzedine came over to do some windows, and Andrée Putman came over to do the store. It was too difficult and too expensive and too long a project to build the shop out, so the decision was made to keep 313 Rodeo very spare and let the clothes and the few pieces of Eileen Gray furniture that we stuck in dictate what it was going to look like, which was a very good accommodation. The demand [for Alaïa] was absolutely soaring. It was a moment when clothes went from whatever they had been to being body-conscious. The quality of his manufacturers was extraordinary. It wasn’t the $76,000 haute couture that it became at some point; it was urban street clothes. That was a time when Mr. Chow was across the street from us on Camden, and Basquiat was handing over art to Tina [Chow] for a meal.

What was it like working with Andrée Putman?

She was lovely. She was not a young woman, but she looked fabulous in Azzedine suits, which she wore with white Fruit of the Loom T-shirts. That was her signature.

You had a number of celebrity clients too, like Anjelica Huston, Paloma Picasso, and Goldie Hawn…

Cloris Leachman was in almost every week stubbing out customers’ cigarettes. Everyone wanted the clothes. It was different than really cool Nikes and Lululemons… You know, people actually paid for their clothes back then. Giorgio Armani screwed it up by paying an actress in the ’70s to wear only his designs, and then it became a thing. There certainly had been associations before, but suddenly, instead of buying dresses, they were getting studios and stylists to buy them. It was very strange.

What were some of your favorite pieces from that time?

Alaïa’s classics were the most appealing at that time, like the body that went with everything. That was very influential on Donna Karan of course. I also loved the cut-and-sewn pieces, which were not as large a group as the knits were back then. They were extraordinary shapes. It was just all wonderful.

Were you wearing Alaïa yourself?

I was more working class. I loved Alaïa, and I would wear my pretty fashion-y clothes when I went on my buying trips, which we all did back then, but I wasn’t walking around in a skin-tight skirt when I was dropping a kid off at school. For everyday, I was a Kenzo person. I just loved Kenzo Takada’s clothing. This was California. Everyday wasn’t fashion.

Did you hold onto any of those pieces?

I wish I had. I never considered that the excitement of a new pretty thingy would end. I was just giving clothes away, saying, ‘I don’t think I’ll wear this anymore…’ I kind of believed if you hadn’t worn it in a year, you should get rid of it. I do miss a few Manolos that I let go.

In 1988, you opened your own boutique, Madeleine Gallay…

After my divorce, I opened on Sunset Plaza directly across from my former husband. It was very different. I was bored with museum-looking stores—black and white, no music, no fun—so my store was pink. It was personal and very female.

I brought in Galliano, who was 26 years old. He was just so genius. Back then, he could only use stock fabrics because he had no money and was constantly being abused by backers. His clothes did not fit at all—I had to fix everything that he shipped from London—but they were incredible and were a preview of what he would become. I also carried Dolce & Gabbana, Rifat Ozbek, Chantal Thomass, Eric Javits, Erickson Beamon, Ghost London, Manolo before he was really huge, and so many accessories. And I would never mark anything down.

I knew a lot of the people who came in. They would have drinks at Le Dome next door. They could come to my house—I lived a few blocks away—to borrow an evening bag or whatever. I lived with my best friend, Angelo DiBiase, who was one of the first major Hollywood hairdressers. Adam Shankman, who is now off directing Only Murders in the Building, was my assistant. That was a time when people wanted to work in shops. It was fun. It wasn’t the money business that it became—the doctor’s wife syndrome and then the designer syndrome. Sarah Jessica Parker once mentioned that she began her fashion buying experience at my store.

I closed the store in 1994. I had a one-year-old at that point, and carting a one-year-old around with the amount of travel was not working. After that, I became a stay-at-home mom.

What do you think of fashion today?

I was always in it, frankly, for the clothes. I loved the clothes, and I loved buying them—I was not exactly a Dolce & Gabbana person personally, but that was still so exciting. I still pay attention to fashion, though I’m shocked and saddened. When I would go to Barneys in Beverly Hills I would of course look at their Alaïa selection, and they would have these incredibly heavy intricate knits being stretched out on hangers. I wanted to go in and fire people for the way that they began to do shopkeeping.

Perhaps this can explain how I see it now: I have a Fendi embellished Oyster bag and the button fell off, so I went to the Rodeo Drive store and presumed that they would be able to deal with this. They asked me if it was a fake. They don’t know what they’re doing. They don’t understand the house that they work with, and that’s sort of what a lot of this is now. Things change, styles change—it can be casual, it can be whatever it wants to be—but there’s not a soul connection, so to speak, with a lot of what’s going on today. I have no objection to street clothes or to really expensive things, if there’s some intrinsic value, but my eyes roll at some prices because I do know what’s involved; if it’s $7000 or $8000 and it’s not luxe and I can get the same thing at Free People, give me a break. It’s insulting.

As told to Zoe Ruffner

INSPIRED BY...

Alaïa

'80s Jupe Asymétrique en Cuir

Taille: 38 FR

Chez ReSee, chacune de nos pièces vintage ont une histoire. Cela en grande partie grâce à notre communauté imbattable de collectionneurs.

Vendez avec nous