We’re thrilled to share a guest post from Sarah Keyes, Assistant Professor of History at the University of Nevada, Reno and author of American Burial Ground: A New History of the Overland Trail. On the occasion of the first day of summer, today’s post examines the complex and tragic history of the Overland Trail, which many a summer road trip is sure to traverse.

The road trip is an American tradition, and this summer, record numbers of Americans are predicted to pack their cars and hit the road. Many of them will follow the routes of historic road-trippers, including overland emigrants who crossed the continent on the Overland Trail in the mid-nineteenth century. For more than two decades, these emigrants traversed multiple pathways across the continent on their way to Oregon and California. Today their routes parallel multiple highways including U.S. Highway 30 from Nebraska to Wyoming and Interstate 80 from Wyoming to California.

For the past few months, the California Trail Interpretive Center located just off I-80 in Elko, Nevada has been promoting itself as the place to learn about the “original family road trip.” The center’s slogan captures contemporary misunderstandings about the legacy of the Overland Trail. While nuclear and extended families crossed the continent in the summer and saw the sights along the way, these white settlers were also agents of U.S. colonialism who directly and indirectly wreaked violence against Indigenous peoples. In the summer of 1860, emigrants traveling west on the road that runs by the California Trail Interpretive Center petitioned and received a U.S. military escort across Nevada. After escorting nearly two hundred overlanders through the state that summer, Officer Stephen H. Weed stationed his forces in the Ruby Valley of eastern Nevada, a station from which he patrolled the Trail for the rest of the summer. By the time he returned to Camp Floyd near Salt Lake City in late September, Weed and his men had killed approximately forty innocent Native people. The National Park Service (NPS) and the Bureau of Land Management, who manage many Trail sites, have been working to center Native perspectives on this emigration. As that work continues, it will be important to grapple with darker legacies of the Trail, just as the Department of the Interior is working to grapple with the traumas of Federal Indian Boarding Schools.

Before emigrants began traveling the Trail in great numbers in the 1840s, many thought of their journey as a historic and triumphal road trip. For these would-be travelers, reaching the Pacific represented the culmination of national destiny that had pulled settlers westward since the Mayflower first landed at Plymouth in the seventeenth century. But the cholera epidemics of 1849-55 converted the Trail from simply a road into the world’s longest cemetery.

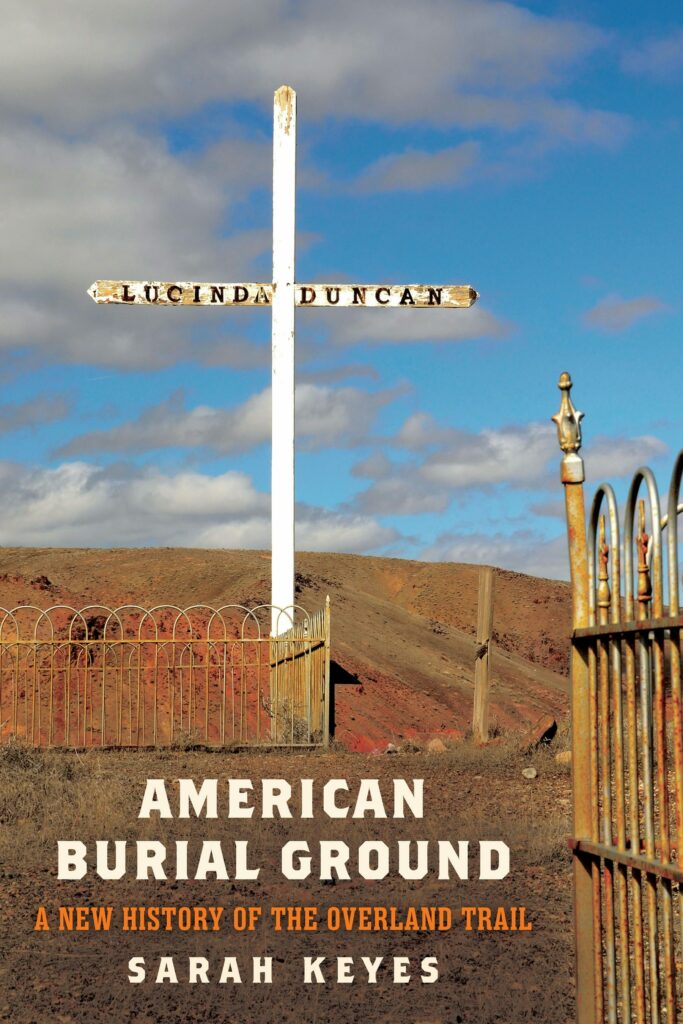

Approximately 6,600 emigrants died along the way, but the legacy of these dead is best measured in how they helped claim the nearly 2,000-mile Trail, and the West more generally, for the United States. Emigrants struggled to properly bury and mark their dead. Instead of the orderly, gridded cemeteries of the United States, burial parties had to make it up as they went along. Some searched for hills and other rises to make graves more visible to passerby, others looked for the comfort of a bending tree (hard to find in the arid regions of the West) or a river whose sounds, emigrants believed, would provide some companionship for their dead. After burying their relatives or friends, emigrants wrote letters describing the location of these graves. But even so, many were lost.

Overlanders’ failures to mark the dead led to the idea of Trail graves as both nowhere and everywhere. Since graves were not properly marked, any apparent disturbance of the soil, unusual arrangement of rocks, or other unremarkable geographic features might indicate the presence of non-Native bones. In the late nineteenth-century settlers along the Trail route, including in states like Nebraska, went searching for emigrant graves to find and mark white history in Native homelands. Some of these graves, including Rachel Pattison’s and George Winslow’s, are roadside attractions today. When Gabrielle Burton and her family took a road trip across the Trail a few decades ago, seeing graves like Rachel’s made Burton reevaluate the legacy of the Trail as one of emigrant death. Burton is not alone. Today, white Americans continue to travel the world’s longest cemetery and some hunt for yet undiscovered emigrant graves, often with cadaver dogs. These twenty-first-century searchers are using different tools, but they are continuing the same process of discovering and marking emigrant graves that began in the nineteenth century.

This process ignores what is, in fact, the key legacy of the dead of the Overland Trail: their role in United States dispossession of Native peoples. In dying along the way and in being buried in Native homelands, dead emigrants helped sacralize the West for white Americans. Their power to accomplish this rested on ongoing territorial struggles that centered graves in nineteenth-century discussions of home and territorial control and in the enduring efforts of relatives and white settlers to mark the dead. American road-trippers who visit Trail sites this summer are participating in this same process. Breaking it requires understanding the history of the Trail as the creation of an American burial ground.