Louisiana’s unforgiving anti-abortion law asks doctors not to be doctors.

Under threat of a long imprisonment, physicians are precluded from offering the best, safest and most humane treatment to women experiencing miscarriages or some pregnancies that are not destined to end well, except under stringent circumstances concocted by a bunch of politicians.

We’ve already seen the practical impact of the state’s trigger law, which was written to take effect upon the reversal of Roe v. Wade, as well as a web of other laws restricting abortion. Consider the woman whose water broke at 16 weeks, and who was forced to deliver a non-viable fetus when the hospital’s lawyers denied her the standard treatment in such cases, a far less difficult procedure known as a dilation and evacuation.

“She was screaming — not from pain, but from the emotional trauma she was experiencing,” during delivery, the woman’s doctor said in an affidavit supporting a lawsuit challenging the state law.

And now, lawmakers who pushed the ban are asking lawyers not to be lawyers.

That’s the upshot of a statement by the trigger law’s author, state Sen. Katrina Jackson, D-Monroe, and a few dozen of her like-minded legislative colleagues.

They took issue last week with the legal minds at Woman’s Hospital in Baton Rouge, amid furious blowback over the hospital’s denial of an abortion to a patient carrying a fetus without a skull that, to the woman’s heartbreak, had no chance of survival.

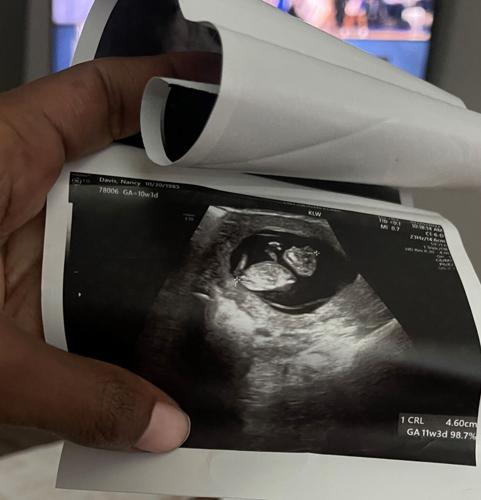

Upon diagnosis of a condition known as acrania, Nancy Davis’ doctors first offered to end her pregnancy, but were then overruled by the hospital’s lawyers. The hospital instead advised her to go out of state to get the care she needed.

Acrania was not initially specified on the state’s list of accepted conditions that would allow for abortion under the trigger law, although it’s now being added. There is a broad exception for any “profound and irremediable congenital or chromosomal anomaly existing in the unborn child that is incompatible with sustaining life after birth in reasonable medical judgment,” but that wasn’t enough to give the hospital’s lawyers the comfort that its doctors wouldn’t be targeted based on other legislation on the books.

“In the absence of additional guidance, we must look at each patient’s individual circumstances and remain in compliance with all current state laws to the best of our ability,” Caroline Isemann, a hospital spokesperson, said in a statement.

As horrifying as Davis’ story is, that’s actually what lawyers are supposed to do: Protect their clients from penalties under the law, as written. And state law paints a great big target on practitioners’ backs.

Politicians will always be politicians, though, and Jackson's statement put all blame in Davis’ case elsewhere. It said that the hospital “grossly misinterpreted” the legal exceptions, and that “the law in conjunction with the emergency rule is very clear that this young lady is within the exception.”

What a cop-out. It’s the authors of years of legislation, those without expertise in fetal development and maternal health, who built the minefield that women, doctors and the people who protect them legally must now traverse.

No laws or regulations can anticipate every circumstance, and even if they could, the impulse to practice defensively will always be a factor as long as the law takes a punitive view of health care.

And then there’s this: Nancy Davis’ quest for treatment ran into a brick wall in one of the state’s major cities, where there are resources, expertise and enough knowledgeable physicians to provide the second opinion that the trigger law requires to declare a pregnancy medically futile.

What’s going to happen to women who, in an emergency, go to one of the state’s rural hospitals where that’s not necessarily the case?

Wherever they live or seek care, Louisiana’s women are now forced to ponder whether they’d rather have lawyers or politicians making their medical decisions.

Where are women who don’t like either of those options supposed to go, other than to another state?