Steven Hale first began covering the death penalty for the Nashville Scene a decade ago.

Convicted murderer and rapist Billy Ray Irick was set to be executed on Oct. 7, 2014, but the Tennessee Supreme Court delayed the execution due to a lawsuit related to secrecy surrounding the state’s lethal-injection protocol. Hale — who at the time reported on myriad issues for our publication, including criminal justice — watched the case closely. As closely as anyone could.

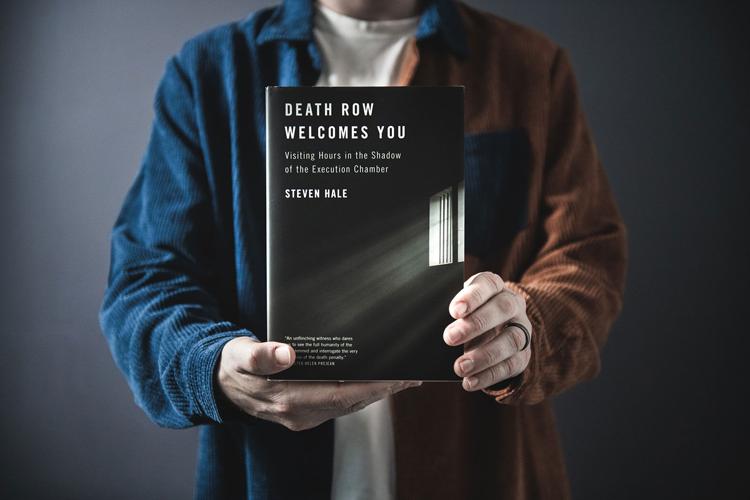

Ultimately, Irick was executed by lethal injection on Aug. 9, 2018, at Riverbend Maximum Security Institution in Nashville. It was the first in a spate of executions carried out at the prison — seven over the course of about a year-and-a-half — and the first in Tennessee since 2009. Hale was among the few media witnesses selected via a Tennessee Department of Correction lottery to watch the killing in person. That was the first of three executions he would observe during his time as a reporter for the Scene, and part of a process he describes in his new book, Death Row Welcomes You: Visiting Hours in the Shadow of the Execution Chamber, as “barbarism dressed as bureaucracy and armed with legal jargon.”

“After Billy Ray Irick’s execution, which is one of the ones I witnessed, I got an email from a man who’s in the book quite a bit, Al Andrews, who is one of the members of this community that I write about,” Hale tells me on a recent afternoon at the Scene offices. “He reached out to me and said, ‘Hey, we’re going to be having kind of a memorial service for Billy Ray Irick, and I read your coverage of the execution and of his life.’ And just for whatever reason, he was moved to invite me to this.”

Talking to Steven Hale about his new book ‘Death Row Welcomes You,’ and to contributor Brittney McKenna about Kacey Musgraves’ new record

That invitation blossomed into a network of relationships that inspired Death Row Welcomes You, out March 26 via Melville House. As much as the book centers on Hale’s experiences covering the death penalty in Tennessee, it focuses just as much on the community surrounding the state’s condemned men — the people who refuse to look away.

“The folks on death row are often kept at a distance from society,” Hale says. “Not just physically at a distance, but their stories and their humanity are kept behind a wall there in a way that does make it easier for it to remain abstract. And we don’t have to confront what we’re doing.”

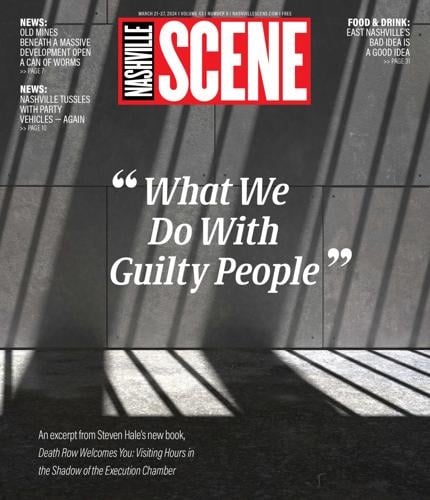

“I feel much more passionate about the question of what we do with guilty people,” he says when asked if the process of writing the book changed his own personal outlook on the death penalty. “Early on, I was — and I still am — very interested in innocence cases. And I think obviously, those are incredibly important … and the work that the Innocence Project and other organizations do around people who are wrongly convicted is hugely important. But almost everyone that I write about in the book is guilty, admittedly. [Writing the book has] made me much more interested in that question: ‘OK, well, what does it mean that someone could commit this horrible crime, and then later be this person? And how do we handle that as a society? How do I look at them as an individual?’”

Hale left the Scene in 2022 to pursue investigative work, but he’s back in journalism once again — he recently joined the team at the newly launched Nashville Banner, where he’ll continue his work covering criminal justice.

Here you’ll find a short excerpt from Chapter 5 of Death Row Welcomes You. The excerpt centers on Hale’s October 2018 visit to Riverbend’s Unit 2, home to all of Tennessee’s male death row prisoners. There he meets others who have formed relationships with death row inmates — “people associating themselves in ink with men the state was determined to kill.” These are advocates who believe, as Hale writes, that “the best way to expose the inhumanity of the death penalty was to expose people to the humanity of the men condemned to it.” —D. PATRICK RODGERS, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Steven Hale

On a Monday night in early October, around two months after Billy’s execution and a few days before another, I made my first visit to Unit 2 at Riverbend. I had seen the death, but not the row — the dying, but not the living.

Shortly before 5 p.m., I met [death row activist David Bass] and [his therapist and fellow activist Al Andrews] in a parking lot on the west side of town and climbed into the back seat of David’s car. They were buzzing with the energy of people going to see friends. The return of executions had brought a weight to their evenings on death row and forced the reality of the place into clear, distressing view. But to David and Al, these visits were still life-giving. And they seized opportunities to bring new visitors into their peculiar community.

The men on Tennessee’s death row who have visiting privileges are allowed to designate eight people, in addition to their immediate family members, who can visit them once a week. But they can also invite others to come as guests for special visits, subject to the warden’s approval. So, by meeting David or Al, a person was suddenly just one degree removed from the men on death row. With permission [from death row inmate Terry King], they had invited a number of people out to the prison — friends, family, professional acquaintances, well-connected businessmen, and me.

But their drive to introduce people to Terry and the other men on death row wasn’t just an outgrowth of their sociable personalities. It was a conscious and, to some, subversive act. David and Al, along with many of the other regular visitors, had come to believe that support for executions, or indifference to them, could not survive a Monday night with the men facing them; that the best way to expose the inhumanity of the death penalty was to expose people to the humanity of the men condemned to it.

We started driving out toward the prison, winding through industrial areas and working-class neighborhoods that were rapidly gentrifying. We passed the Walls [Tennessee State Prison, which closed in 1992 but still stands not far from Riverbend], where many of the men we were going to see had started their time on death row.

It had been around four years since David drove out to Riverbend for the first time. After [an invitation from Joe Ingle, an advocate and spiritual adviser for death row inmates], he’d eagerly told everyone in his life about his plans, which seemed to them to be a sign of an ongoing crack-up.

“We’ve got the kind of family with the picket fence,” he said when he first told me the story. “And all of a sudden dad and husband comes home going, ‘guys, I got this great idea, I’m gonna go to death row’ and everybody looked at me like I was crazy. And some of ’em still feel that way. But most of the family has come around on it.”

Four years later, David’s wife, Michelle, had still never met Terry and he didn’t think she ever would. He attributed this, at least in part, to her past experiences with murder and the trauma that emanates from it. She’d worked for the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, and taken part in the autopsies of victims, including children. David was open about the fact that his relationship with Terry and the other men he’d come to know on death row had complicated his marriage. But he did not expect his wife, or anyone else in his life, to share the passion he’d fallen into. One of their two sons had visited Terry, though. And to their two daughters, Katie Ann and Caroline, he’d become like an uncle. They corresponded with Terry regularly and often visited him with David when they could.

But the man who later felt comfortable bringing his then teenage daughters along for visiting hours at the prison would be unrecognizable to the one who showed up to Riverbend on his first Monday night. Sitting in his car in the prison parking lot that evening, before leaving his phone and heading inside, David sent a final text to his family and loved ones, as if he might not make it out.

“I’m going in ...”

His friends on death row would tease him about this for years.

But the man who went into Riverbend that night didn’t really make it out after all. That first Monday night visit upended David’s life. He met men he previously would have simply called murderers. And they were murderers, of course. But as he sat with them, he realized that was a lie by omission. These men had not been wheeled out on a dolly to speak to him from behind a leather muzzle. They were sitting unshackled before him, looking into his eyes. They even seemed to care about him. He felt destabilized in their presence, not because they were menacing but because they were not.

The first man David met that night was Abu-Ali Abdur’Rahman, a slight, Black man known among the community of people close to death row simply as Abu. He’d been sentenced to death for his role in the 1986 killing of a small-time drug dealer named Patrick Daniels and the stabbing of Daniels’ girlfriend, Norma Jean Norman, in Nashville. His case had become well known for its myriad problems, not the least of which was an overwhelmed defense attorney who later admitted he’d hardly given Abu a defense.

But it wasn’t the injustices of Abu’s case that left David feeling, as he put it to me, like his whole world was breaking down. It was the fact of the man himself, whose peaceful presence seemed to contradict the very premise of the place where he was confined. In more than thirty years on death row, Abu had maintained a deep interest in spirituality. He’d adopted his name after converting to Islam. Later, he converted again and was confirmed as an Episcopalian in a service on death row where he sang “Amazing Grace.” Among the several degrees he’d earned during his incarceration was one as a mediator, and he was an active part of a conflict resolution program in the unit.

After Abu, David met Terry, who told him a story of murder, yes, but also a curious story of redemption, one deemed impossible by the sentence handed down before Terry turned twenty-three years old. David would recall how uniquely present Terry seemed, and how aware he was of the overwhelming effect that the setting could have on a first-time visitor from the free world. Occasionally during their conversation, he would reach over and gently touch David’s shoulder, asking “Are you OK?”

Toward the end of their visit, Terry asked David a question that he regularly asks new visitors. For David, who had already lost his sense of equilibrium, it was the blow that knocked him over.

“How do you feel about the death penalty?”

David didn’t really answer. He stammered through a response, finding that he was unable to look this man in the face and tell him, “As it happens, I think people like you should be exterminated.” He left the prison in an existential fog. A couple years later, though, after spending many Monday nights at the prison, he went to death row and told Terry about that old line he used to repeat about the condemned, that “we need to fry ’em until their eyes pop out.” That was how he felt, he said, and he asked for Terry’s forgiveness.

We arrived at Riverbend around 5 p.m., about the same time I’d arrived for Billy’s execution, only now it was quiet and still. There were no armed guards at the top of the driveway, no white tent prepared for a press conference. We got out of the car and walked toward the entrance, assured that everyone we saw in the prison that night would be alive when we left.

A small group of men and women sat on benches outside the prison’s front doors. They greeted us like regulars at a neighborhood bar, and David introduced me around.

Like us, they were waiting for visiting hours to begin. Some were going to death row, others had family members in the prison’s general population. One of the women was the mother of a man whose crime and trial had made national headlines. David had gotten to know her well and soon they were laughing, but she looked to me like a person smiling from behind a veil of grief.

Sitting there on the benches, as afternoon turned to evening, the group seemed a lonely few. But they are not, of course. Around two million people are incarcerated somewhere inside America’s sprawling system of prisons and jails. On that day, more than 2,700 people were languishing on death rows around the country. For so many of those locked-away men and women there are people like these, people who have not forgotten them.

Soon, the small group started jokingly bickering about who would go first through the door, risking the ire of the corporal who was perched at a desk behind the security checkpoint. She was short in stature and in temperament and particularly intimidating to uneasy newcomers. This tension did at times give way to some levity, though. Alvaro [Alvaro Manrique Barrenechea, a friend of Billy Ray Irick] had told me how his long last name used to peeve the corporal when he first started visiting Billy but eventually became a sort of running joke between the two of them. David, who seemed to view tough personalities as a kind of challenge, worked to win her over. Still, the visitors found her whims somewhat difficult to predict. Visitation began at 5:30 and the group was typically allowed to come inside around 5:15 to start going through security. But on the wrong day, for reasons that were not always obvious, they might be bluntly told to go back outside and wait longer.

Billy Ray Irick was lying on a gurney, eyes closed and snoring loudly at 7:34 p.m. on Aug. 9 when Tony Mays shouted his name.

An even bigger hassle, though, was the prison’s dress code for visitors, the enforcement of which seemed to ebb and flow on an arbitrary basis. This trouble mostly affected the women, whose outfits were scrutinized according to the visitation handbook’s various dictates. A visitor’s attire could not be “provocative or offensive to others”; clothing was to “fit in an appropriate manner,” neither too tight or too loose; underwear was required, but underwire bras and thongs were banned, as were pieces of clothing with rips in them, such as a pair of jeans with a hole in the knee. After a while, most of the women who visited the prison regularly had cordoned off a collection of approved clothes in their closets. But they found that even an outfit they’d worn multiple times without incident could get them sent back to their cars or their homes for a wardrobe change. Looming executions also seemed to put the guards on edge. On the Monday night before Billy’s execution, the visitors had seen an unusual number of people turned away for minor violations.

On this night, though, we made it through security without any problems. After passing through the metal detector and the body scanner and retrieving my belt and shoes on the other side, I approached the desk where the corporal oversaw the proceedings. With David’s direction, and the corporal’s prodding, I leaned over a large black binder and wrote Terry’s name and the Department of Correction ID number assigned to him—103308—followed by my own name. We repeated the same process in another binder designated for Unit 2 visitors. Its pages were a picture of radical solidarity, a catalog of people associating themselves in ink with men the state was determined to kill.

We waited quietly for a moment before the corporal waved us out the door and down the same path I’d taken to the execution a couple months before. We walked through the first of the two tall barbed-wire gates, waiting for it to close behind us before the next one would open in front of us. From there, we entered the central building that houses a large visitation gallery for men from the general population. Some of the visitors left us there to find a seat with their loved ones. Soon, an officer arrived to escort the rest of us to death row.

As we made our way down a long sidewalk, I saw what looked like large rectangular cages with concrete floors outside the unit buildings. A tiger pacing back and forth in one of them would not have looked out of place. Several of the regular visitors had told me about how the men on death row often spoke about how long it had been since they’d stepped foot on grass. I later learned that these cages — surrounded by grass the men couldn’t quite touch — were as close as they got. Small red signs beside the sidewalk urged us to stay off the grass; they felt almost like taunts.

When we arrived at Unit 2, we stood outside a heavy metal door, waiting for the guard seated at a desk inside to unlock it. We stepped inside, crowding into a small space between the first door and a second, waiting again for a door to close behind us before another could open in front of us. We each handed the guard a slip of paper we’d been given at the security checkpoint, to prove, I suppose, that we hadn’t gotten to death row’s door by some other means. With that, we were in.