Take I-24 East from Manchester. The dark band of the Cumberland Plateau looms above the horizon, its forests hiding beds of limestone, sandstone, shale and coal. Pastures along the highway glow the neon green of early spring. Near mile marker 125, a double billboard appears. One sign touts Ruby Falls, and the other bears two lines of print: “River Gorge Ranch. A New Mountain Community.” The background is pleasantly artistic, with imagined peaks and a stylized blue stream. It could be the cover of a fantasy novel.

It does not mention coal mines.

Cruise down the Monteagle grade, crossing the impounded Tennessee River near Nickajack Dam. Aetna Mountain looms ahead, a dun-colored scar zig-zagging toward the peak: the future entrance to River Gorge Ranch (RGR). Take the Haletown exit for the visitor center, in a building that once housed Big Daddy’s Fireworks.

The splashy development brochure, disguised as a magazine called Tennessee Mountain Living, shows Gov. Bill Lee breaking ground on the site as proud owner and developer John “Thunder” Thornton looks on. An article boasts the endorsement of “ambassador” Jim Nantz, who in a promotional video calls RGR “a peaceful and luxurious escape.”

Lots at “Tennessee’s Premier Mountain Gated Community” sell for up to $600,000, depending on the view, with approximately 300 sold and more than 2,500 in projected sales. RGR will include three “Amenity Centers” with recreation, shops and restaurants (all run by Thornton).

Prospective buyers can take a Jeep tour up the rutted track — not that there’s much to see. There are no finished roads, electricity, water, sewer or model homes. Instead, after enjoying the Aetna views, customers can see models across the valley in Thornton’s previous development, Jasper Highlands.

The brochure explains: “The first phase of River Gorge Ranch will always be remembered as the Founder’s Phase — a collection of properties for pioneers, adventurers, and visionaries; those who step out onto the land before the first road is paved and yet understand the power of this one-of-a-kind location.”

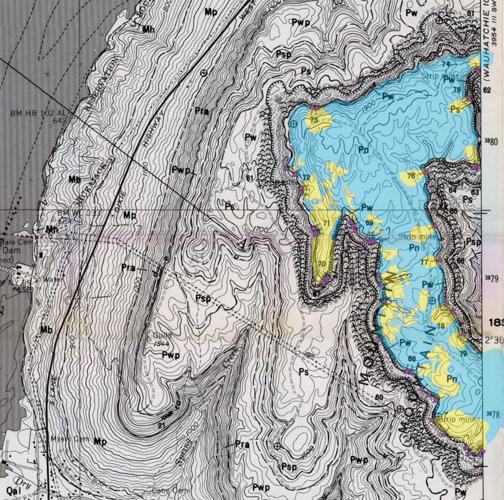

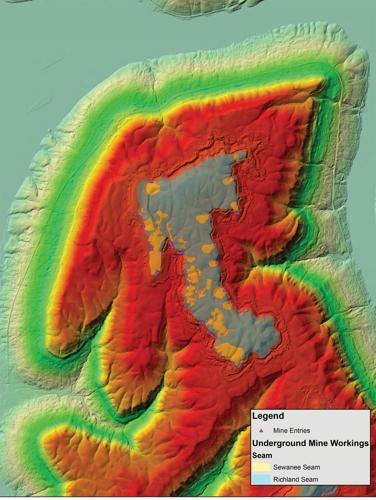

“Power” is a good word choice. The location sits atop what locals call a “Swiss cheese” of abandoned coal mines, some dating back to the 1840s. Entrances and air shafts — most now hidden by dirt or concrete — line Upper and Lower Strip Mine roads (to be renamed once they become major RGR thoroughfares). For decades, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention studied the collapse of room-and-pillar coal mines. Anyone trying to sell a house above such a site would be required to disclose risks to potential buyers, who might need to purchase subsidence insurance. Tennessee law, however, does not require disclosure for the sale of undeveloped land.

Aetna Mountain

Mike Bailey retired from his role as lead wildlife officer at the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency after decades spent working on Aetna Mountain. A biologist by training, he helped remediate some of its former strip mines, bringing back native flora and fauna.

“There’s strip pits and deep shaft mines all over the entire mountain,” Bailey says.

Aetna once held a thriving community with houses, a store, mine headquarters, a church and a cemetery. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, state prisoners were released to the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company as convict labor.

“In the back of the cemetery, graves are either unmarked, or they simply marked the rocks on the ground,” Bailey says. “Those prisoners died mining for coal.”

He recalls a more recent strip mine on the west side of Big Ridge. “It exposed a whole row [of older mines],” he says. “You could look up on the side of the cut and see the old deep shaft mines that went through the ridge, one after the other.” In addition to mines and shafts at the top of the mountain, Bailey has seen “deep mine shafts in the hollers,” referring to canyons like Moroney Gulf, which extends just below the planned location for RGR’s still-unnamed “Amenity Center No. 2.”

The blue sections indicate the major coal seams on the mountain. The small yellow shapes around the edges represent coal mine outlines.

In 2006, photographer John Mulhouse was hired to shoot Aetna Mountain for a biological survey conducted by a forestry company. He entered and photographed two mines on the mountain, noting that sometime after the mines were abandoned, locals had illegally extracted coal by removing some pillars. To avoid collapse, they propped the ceiling up with tree trunks. Mulhouse said “bad air” eventually chased him back outside. The log supports he photographed presumably remain, slowly rotting away.

Land subsidence is common above old room-and-pillar mines — especially where pillars have been “robbed,” as at Aetna. As construction industry publication Structure put it in a 2020 article on building over coal mines, “given the investment, having correct risk information is critical to proper decision making.”

Support post in an old mine

Retiree Ronnie Kennedy was determined to share such information with the unsuspecting purchasers of property at RGR. An amateur historian who “knew every inch” of Aetna, in the 1980s he supervised an active strip mine on the mountain. Kennedy had known the owner’s family since the 1950s. After the owner died, his widow gave Kennedy boxes of mine maps and other Aetna historical documents, some dating back well over 100 years. He lives in a trailer on Aetna Mountain Road, just below the property line where the road to the top became private three years ago.

Many of Kennedy’s neighbors knew of the mines, but most feared reprisals from Thornton should they speak out publicly. Even so, a few concerned citizens decided to help get Kennedy’s maps into the proper hands. The maps reached a mine expert in the U.S. Office of Surface Mining. He combined their data with Aetna topographic and LIDAR maps. These new maps showed that as many as 30 underground mines, some of them enormous, tunneled beneath current and planned development areas. And they depicted dozens more known entrances beyond those shown on the old mine plots.

Armed with the map data, staff of the Land Reclamation Section of the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC) reached out to Thornton’s consulting firm, Davey Resource Group Environmental Consulting. TDEC offered to visit the site in 2023 to locate and identify mine-related land features. According to TDEC spokesperson Kim Schofinski, “After consulting with their client, the consultant declined our offer.” She says TDEC’s policy is to honor such wishes “unless an imminent health or safety hazard is known.”

The consultant ultimately declined inspection twice.

Plotted lot sales above mines

Undeterred, Kennedy sought to have the maps introduced by the Marion County Commission, saying he was concerned for out-of-state residents spending great sums on dream homes with no knowledge of the potential problems. While some commissioners work frequently with Thornton, others were sympathetic to people helping Kennedy get the word out.

At the Jan. 29 county commission meeting, Kennedy planned on introducing his maps, but unrelated complaints from another citizen caused the chair to shut down all public commentary at the meeting before Kennedy could speak. (The chair had the sheriff remove the speaker from the room.) This led a state official to visit commissioners in advance of the February meeting to run a workshop on when and how to allow public commentary.

Before the Feb. 26 meeting, three commissioners agreed to introduce Aetna Mountain as an agenda item, allowing Kennedy to speak. More than an hour into the meeting, Commissioner Paul Schafer spoke before inviting Kennedy to the podium.

“I have received calls from residents regarding issues of closed mines on Aetna Mountain,” Schafer said, adding that he believed the developer should disclose their existence and potential problems to future buyers. With that, he introduced Kennedy as a “longtime resident.”

Kennedy approached the podium slowly, then spoke in a soft Southern voice that the microphone barely picked up. Holding a thick envelope of maps, he described the mining history, pausing as commissioners jumped in to share their own stories.

One mentioned that Billy Gouger, the county attorney, had played in the mines as a boy. Another, a retired state forestry technician, described supervising a crew putting out a forest fire when a sudden collapse swallowed a bulldozer to the top of its treads. A larger bulldozer had to be brought from Prentice Cooper State Forest to extract it.

“I tried to bring this to the right people’s attention,” Kennedy said from the podium. “But who am I, you know?”

“There’s a coal seam up there that burned underneath the ground for years and years,” said Commissioner Gene Hargis, chief detective for the Marion County Sheriff’s Department.

As Hargis continued, county Mayor David Jackson put his hand to his forehead and shook his head in evident disbelief at the direction of the conversation.

Hargis, seated beside him, failed to notice. “I don’t know if it still is up there, but it burned several years.”

“Last I heard, it was still burning,” Kennedy said. “They tried to cap it with concrete.”

“I hadn’t saw any in years on ‘Et-knee,’” Hargis said. “But when I first started working the sheriff’s department, we’d be up there, and you could warm your hands by [the rocks] in the wintertime.”

“Once it gets burning, you can’t never put ’em out,” Kennedy said, mentioning the ruined coal town of Centralia, Pa.

After much discussion, the commission took a recommendation from Gouger to bring the issue to the developer, asking what mitigation efforts he had taken. Gouger expected they would deliver an answer before the next meeting, scheduled for March 25.

The next day Commissioner Ruric Brandt, one of those who had supported putting Kennedy on the agenda, said strangers were calling him to say he should keep asking tough questions.

“Marion County has been kept in the dark,” Brandt said. “The lights are finally turned on.”

Next up: Water, sewer and buyers still in the dark.

See part two of “Thunder on the Mountain” next week.