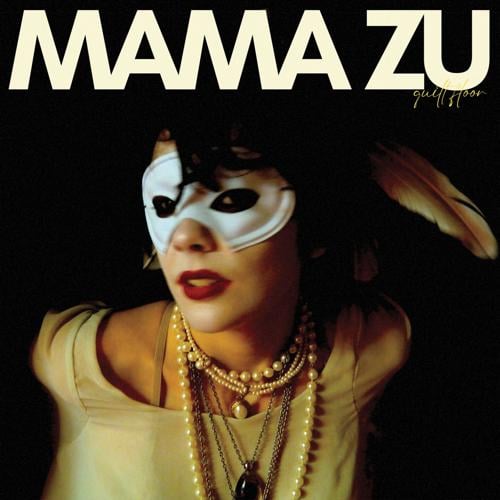

Friday, Nashville rock ’n’ roll duo Mama Zu releases its debut album Quilt Floor. But the voice and vision of the group won’t be able to participate.

Jessi Zazu, who was also a founding member of beloved Middle Tennessee rock act Those Darlins, died of cervical cancer in September 2017, before sessions with multi-instrumentalist and producer Linwood Regensburg — Zazu’s fellow former Darlin and the other half of Mama Zu — could be finished.

But now, nearly seven years since the pair entered the studio, Zazu’s final creative endeavors are making it out into the great wide world. Quilt Floor is an album of amazing energy: Featuring songs with titles like “Emotional Warrior,” “Hole Thru My Head” and “Made of Dreams,” it’s confrontational and questioning, equal parts empathy and hilarity. It’s the sound of a country girl with cosmopolitan concerns giving the universe a quick jab to its uncaring chin.

“It’s not like this was being made because Jessi thought that she was going to die,” says Regensburg, on the phone in January from his snowbound studio in East Nashville. “This was made under the guise of, ‘She’s going to get better, and this will be the glorious part of the story where the hero is back and all the bad stuff is in the past.’”

But the bad stuff wasn’t in the past. In addition to Zazu’s illness, global-scale bad stuff was just on the horizon while this record was being made, and the tapes would be shelved. It was a project without a frontperson — on hold until … well, a moment not dissimilar to the cultural and political climate it was created within. Quilt Floor, both out of time and of its time, is a fired-up and freaked-out self-portrait of a young woman reacting to the horrors of the early Trump era, polished in the claustrophobia of the pandemic, released into the morass of 2024, where that duality feels more right than it should.

“I do think that it can be a positive,” Regensburg says. “You can look at it as inspirational, but that wasn’t necessarily what was happening.”

Zazu was born in Franklin, Tenn., and grew up in Kentucky. She was a creative force from the word go.

“She would sit on [her father] David’s lap while he worked at the table — he did illustration — for hours and hours,” says Kathy Wariner, a visual artist, Zazu’s mother and a co-founder and board member of Jessi Zazu Inc., the arts nonprofit launched in her daughter’s memory. “So she never really took art classes.”

By all accounts, Zazu was a natural artist with a preternatural sense of confidence. After attending early installments of the Southern Girls Rock ’n’ Roll Camp (now the Yeah! Rocks Summer Camp) held at Middle Tennessee State University, she moved to Murfreesboro, drawn to the town’s flourishing and freewheeling creative arts community. She started a band with SGRRC co-founder Kelley Anderson and SGRRC counselor Nikki Kvarnes that tapped into their Southern roots and DIY proclivities.

“Jessi wrote more songs than anyone that I’ve ever known,” says Kvarnes, on the phone from London. After moving to the U.K. when Those Darlins dissolved in 2016, Kvarnes honed her skills as a portrait artist. A mother of two, Kvarnes has recently returned to the world of music, jamming in the living room with neighborhood friends. “In between writing songs, [Zazu would] be, like, having a sketch, a drawing — constantly. ‘Do you ever stop making things?’ She’s like, ‘I gotta get to my garden. I’ve got just a billion projects on all the time.’”

The three bandmates took on the stage surname Darlin and barnstormed their way from the house shows of Rutherford County to stages across the globe. Regensburg, who had built a reputation as an explosive guitarist in a succession of short-lived artsy-punk outfits, joined Those Darlins on drums just a few months before their self-titled debut album was released in 2009. (“It was that simple — I was available,” he says.) Prior to Those Darlins, there was one EP; two more studio albums followed in 2011 and 2013.

“[During] my tenure with Those Darlins, we were just working incredibly hard,” says Anderson. She left the band in 2012, and is now a professor teaching finance at the University of Tennessee Knoxville, where she recently joined the community marching band Honkers and Bangers. “We were out there pursuing the thing, and it kind of consumes your whole life — all the things that you have to do to support the creative output.”

The all-consuming nature of band life suited Zazu, who was a one-woman factory of art and ideas. Her unflagging sense of humor and her need to process the world around her in novel ways would fuel her through often-intimidating expectations of life on the road and in the studio.

“On tour, things get really hard, and sometimes they get kind of dark,” Anderson says. “[Zazu’s] sense of humor was always there.”

“God, she was a tiny girl with freaking punch,” says Roger Moutenot. The renowned producer and engineer contributed to Quilt Floor, and produced both Blur the Line — the 2013 album that would become the Darlins’ swan song — and later sessions for an unreleased album that precipitated the Darlins’ breakup. “She had a lot to say, and saw the world in a really unique way. She had no doubt who she was and what she wanted to say. … She cared about issues in the world and was letting it all out. It was beautiful to see.”

Those Darlins in 2011

That steely-eyed artistic vision would run headlong into the equally entrenched artistic vision of Kvarnes, a woman she had spent nearly a decade living and working and creating with. The two would come to an impasse, complicated further by personal and societal issues encroaching on the sessions.

“The mood was a little tough,” Moutenot explains. “The girls were finding that they wanted to go in different directions. Nikki wanted to do the pop kind of fun stuff, and Jessi wanted to be serious and sing about issues in the world. So there was a little butting heads on that end of it. Otherwise they were best buds and loved each other, but that was just a little quirk in the making of the record.”

“Jessi was going through a whole lot of stuff that she was not [vocalizing] to me, and I don’t know if she was to anyone else,” says Kvarnes. “She was internalizing, I think a lot of pain and anxiety and worry with stuff that was going on, maybe physically with her. I don’t know. There was a lot of stuff going on with Jessi the past two years of the band. … The band wasn’t getting along great for the last two years either. It was up and down, as all relationships are, but creatively, we were having a very hard time connecting because her experience was so different from mine, and I was just on a different thing.”

“When we were working on the Darlins record, [Jessi] would nap a lot,” says Moutenot. “I thought that was kind of weird. And that was the beginning — something was going on.”

The band’s breakup would drag out longer than intended. Those Darlins’ final tour, a string of sold-out dates with ascendant Americana star Shakey Graves, would get snowed out. The makeup dates — contractual obligations that were too lucrative to bail on — would drag out the band’s demise over the early months of 2016. The typically high-energy Zazu seemed exhausted at the merch table, but you would have never known from her onstage persona. Those Darlins would end as they started: a thrilling and thoroughly engaging live experience.

Those Darlins in 2015

“We did our final tour, and then a month later was when she found out that she had cancer,” Regensburg says. After a quick breather, Regensburg and Zazu had been sketching out ideas for the first project of the post-Darlins era. “This is how absurd everything is: The day that we were supposed to get together and just get lunch and make a plan, that was the day things started to go south.”

Following Zazu’s diagnosis, her mom and her brothers Emmett and Oakley moved into her rental in North Nashville to coordinate care. Watching her typically high-spirited daughter dimmed by the early stages of cancer treatment, Wariner noticed that creative work maintained a sense of normalcy for Jessi, and even provided a needed boost of optimism.

“She was in a much better place while she did art or music, but I think she was a little too sick at first to think about music,” says Wariner. “She just was sleeping a lot, then not sleeping a lot — they put you on so much medicine, the chemo and the radiation and all that. So art seemed to be doable.”

Zazu had developed a broad circle of fans and friends between Those Darlins, her continued work with SGRRC and She’s a Rebel, the girl-group tribute show series that brought together some of Nashville’s most talented underground artists to sing the praises — and songs — of the mid-20th century’s beehived badasses. This was a group of friends who would show up and show out. When Zazu announced her diagnosis, her community came out to support her in ways both big and small. They helped her put together an extensive show of her visual art. And as the arduous bouts of early treatment ebbed, they bolstered Zazu’s return to the studio.

“She is a real artist, for real,” says Buddy Hughen. As a member of his wife and collaborator Tristen’s band, the longtime local musician, producer and engineer toured with Those Darlins toward the end of their run, and he came in to record Quilt Floor. Regensburg played most of the instruments, and Zazu sang.

“She was in a pretty weak state most of the time,” Hughen recalls. “We never really talked about her cancer or anything like that. She had an oxygen tank when she was doing vocals. She would sing, and then we would take five and she would just breathe for a while, and catch her breath, and kind of get recentered and do another take. She was really generally in a great mood the whole time, through all that discomfort and stuff.”

Nashville MVP Larissa Maestro, a composer and Americana Music Association Honors and Awards-winning cellist, tours with Allison Russell and Hozier among many more projects. Among those is Quilt Floor.

“She was quite sick,” Maestro remembers of the sessions. “She didn’t have any hair. She was going through treatment I think at the time, and she was quite thin and tired. But she was always still Jessi. She was always still, like, ‘Punch it.’ She always wanted everyone to show up as their full selves, and that was something that [is] really empowering for someone like me, who is really used to going in and molding myself into whatever the person wants from the way that I sound.”

Regensburg, in his role as producer and player of most of the instruments, took voice memos, notes and between-nap conversations and turned them into the bones of songs. With a vague plan to let the songs follow their own path, the tonal palette shifted, expanding beyond Those Darlins’ hillbilly roots and indie-garage-glam final form without leaving them behind entirely. The recordings became a dialogue between two voracious listeners about sounds they love — the songs are a colloquy on the joys of art and creation when life isn’t always joyous.

“When she was dying in the bed on morphine — I mean, it was the last day before she passed away — [Linwood was] in there with a guitar, playing some song parts and getting her opinion about it,” Wariner remembers. “And she could just barely nod or say yes or no.”

Fast-forward three years to the pandemic and a world on pause. Without shows, tours or a recognizable music industry, there were a lot of musicians returning to old ideas, restarting projects long shelved. Regensburg was among them. He spent the years between Zazu’s death recording guitar on friends’ studio sessions and performing with Philadelphia art-rockers Low Cut Connie, enjoying the lowered creative stakes of playing other people’s songs in other people’s bands.

“If I was home, I would maybe pull up a session and try to work on something, but — I don’t know, it wasn’t in any focused kind of way at all,” Regensburg says. “And then late 2020, I still had a lot of time on my hands, and it just seemed like, ‘Oh, this is the time.’ I started to feel this guilt because I’m, like, ‘Oh, I should have started this the moment that the pandemic started.’”

Just as Regensburg was ramping up overdubs, there was another delay. In the process of breaking up a dogfight on a late-night walk through Five Points, Regensburg broke his hand. Quilt Floor is not an album about being sick, but its post-production phase was certainly about healing.

“Finishing this on my own was really isolating,” Regensburg says. “But I also kept finding these little North Star moments in songs that were grounding and joyous, and made me reconnect back with why I wanted to make music in the first place.”

Quilt Floor’s artistic success — hell, its mere existence — exalts the idea of unbridled creation, of artistic minds that can’t be slowed by sickness or grief or commercial interest. Regensburg and Zazu have created a testament to the best thing about an often arduous lifestyle and career path: playing music with your friends. Quilt Floor’s punk spirit and rebel attitude in the face of personal and societal pressure might not have intended to be inspirational, even if the inspiration is just to punch a shit-talker in his jaw.

“It’s an elevation of everything that [Those Darlins] ever made,” says Kvarnes from half a world away. “I lost my dad the year after, and lost a couple people [after that]. It’s been a lot of grief since her, and I’ve never felt something so ‘light at the end of the tunnel’ as listening to this record. It makes me feel like they’re both just right next to me.”

The album’s release party will be held Friday at Retrograde Coffee’s City Heights cafe on Clifton Avenue. It’s a dance party and auction with proceeds benefiting Jessi Zazu Inc., and the last bit of promotion for an album without a frontperson around to do interviews, tell stories and play shows. As Regensburg prepares for the release, it’s natural to speculate about what Zazu would be doing now had things been different. Would she have gone the incense-and-ambient route? Would she be fronting a feminist disco orchestra? Would she have made an album about having been sick? The only sure thing: She had a lot more music and a lot more art inside her.

“It doesn’t get any better than being able to collaborate with another artist you really believe in, and who motivates you to be your best,” Regensburg says. “And even though that time was fleeting, it’s still something to be grateful for.”

Sean L. Maloney is the author of 33 ⅓: The Modern Lovers from Bloomsbury Publishing. He and Linwood Regensburg played their first DJ gig together 20 years ago this week at the Campus Pub in Murfreesboro.

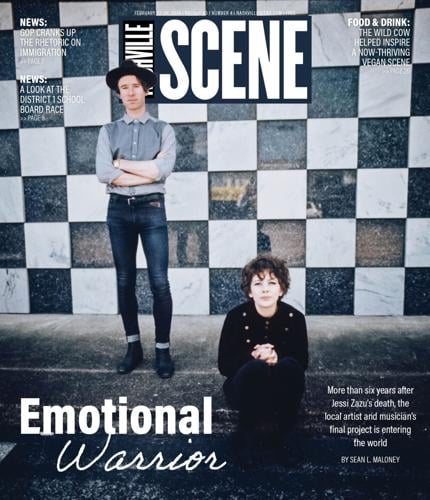

Linwood Regensburg and Jessi Zazu in 2014.