Kunefe

A couple years after Yellow Porch opened in 1998, rising young talent Kim Totzke was named chef. As new chefs do, she embarked on that trepidatious balancing act of honoring regular diner favorites and making her mark with creations of her own. One of those was an exquisite, earthy, deeply flavored lamb cassoulet that I still recall with full sensory gusto.

But another local restaurant critic at the time did not have the same experience, opining that “the lamb cassoulet is too lamby.” It distressed Totzke, but with our mutual friend, caterer Monica Holmes, we turned it into a recurring joke — that beet is too beety, this crab is too crabby, the pork is too porky — that we never tire of.

If lamb is too lamby for you, or if you’ll eat cluck, moo and quack all day long but won’t touch baah, be advised that the meat is prevalent on the menu at Osh. I feel a little sad for you, but there are many other proteins to choose from, as well as rice, noodles and vegetables, at Nashville’s first and only Uzbek restaurant.

Consulting the world wide web, we discover that Uzbekistan is a landlocked country in Central Asia bordered by five landlocked countries, all of which end in “stan.” The Uzbek people are a Turkic ethnic group that lives primarily but not exclusively in Uzbekistan, and Uzbek cuisine is influenced by Asia and the Middle East, with a strong nod to Turkey.

Osh the restaurant took up residence about two years ago in the space formerly known as House of Kabob, which moved a mile or so west on Thompson Lane. OG HOK diners will recognize the two connected dining rooms furnished with dark-brown booths and tables; Osh has adorned shelves with colorfully painted Uzbek tea sets, serving bowls and decorative pieces. Because Tennessee alcohol laws mean it’s easier to purchase a gun than a beer within 100 yards of a church, no alcohol is sold at Osh, a few doors down from St. Edward Catholic Church. You can BYO wine.

The name of the restaurant is a nod to what is considered the national dish of Uzbekistan, osh, also called palov or plof, or in more familiar terms, rice pilaf. At Osh, osh heads the specialties section of the menu and is an entrée not to be missed — but do peruse the other categories for shareable starters and salads, and don’t skip the soups.

While considering the selections, spread triangles of warm pita with paprika-dusted sour butter; no charge for “bread service” here. To begin, we chose the eggplant salad — a chunky mash of eggplant, onions, garlic and bell peppers — to scoop up with the pita; an eggplant spread that adds tomatoes and carrots is another aubergine option. Look into the charcoal grill section and discover lamb shashlik (which translates to shish kabob). Marinated cubes of lamb are skewered and cooked over a grill, which puts a char on the exterior and seals in the juices on the succulent meat. A fully loaded skewer comes with a small dish of thinly sliced white onion and a cruet of mild white vinegar, which our server Umit Cin urged us to sprinkle lightly on the meat. We vowed from that moment on to do whatever Umit — newly arrived from Turkey and as affable as professional — suggested.

Another Uzbek specialty, the lamb manti, is also an excellent starter. Six dumplings reminiscent of Chinese soup dumplings are filled with ground lamb that is sautéed with onions and spices, then steamed and served with minty yogurt that balances the pungent (some might say lamby) filling.

I’ve never described soup as fun, but four grown women were totally entertained by the lagman, another signature Uzbek dish. The soup features a mildly spicy tomato-based broth with small pieces of lamb and large dice of fresh bell peppers, onions, carrots and tomato, but it’s the hand-pulled noodles that put on a show. Curly strands stretch and stretch when pulled out of the soup with seemingly no end; we addressed the issue by pulling as much as we could onto a plate and cutting through to more fork-twistable lengths of chewy pasta.

We were also amused — as will be all adolescent boys — and irresistibly intrigued by a dish called jiz-biz, which traces its culinary heritage to Azerbaijan. The menu describes the chicken jiz-biz as roasted, but the onions, mushrooms, peppers and tomatoes with it harkened more to a braise. Semantics aside, the butter-tender chicken was served with a scoop of rice and more minty yogurt and was one of our favorites of the night. Jiz-biz can also be ordered vegetarian, or with lamb or shrimp.

Speaking of seafood, another highlight was a split whole branzino, skin rubbed with olive oil, simply seasoned with salt and pepper, grilled until the skin crackled and the meat flaked, served with lemon wedges and syrupy cherry tomatoes so good we asked Umit for a side bowl of them.

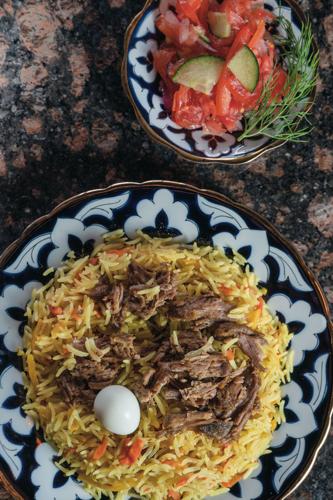

It will surely hurt Osh’s Chef Murad’s feelings if your table neglects to order the osh. The art of osh begins with a base made by sautéing onions, garlic and carrots in fat before adding raw rice, covering with water and simmering until the rice is cooked. The chef adds their own touches to the finished product; our osh/palov/plof was studded with apricots, raisins and currants, topped with a generous pile of shredded lamb upon which a hard-boiled quail egg was perched. The scent and aesthetics were so alluring that even the lamb deniers at the table simply ate around the meat.

Osh

Dessert is rarely on my personal dining radar, but duty called, and we were rewarded with a happy ending that had us equally captivated and curious. Kunefe (kyoon-eh-FAY) is described on the menu as “thin layers of rolled pastry, shredded and baked with cheese.” What comes to the table is a shallow pewter bowl, still warm to the touch; the shredded pastry is similar to phyllo in taste and texture, layered with a mild cheese, lots of butter, sparingly sweetened with syrup, baked, sprinkled with ground pistachios, and cut into quarters. When we asked Umit what the cheese is, he replied “regular cheese.” When I asked Chef Murad the same question, as translated by Umit the reply was the same, “regular cheese.”

There’s nothing remotely regular about Osh. Some measure Nashville’s white-hot national dining profile by the arrival of celebrity chefs enthroned in skyscraper hotels. All well and good, but with boots on the ground, I am more inclined to seek and celebrate every chef, Murad included, who bravely travels from a far-off land and plants their culture and cuisine into the city’s ever more diverse landscape.