Longtime Nashvillian Daniel Lonow first visited Hermitage Cafe as a teenager with his dad, who played gigs at Wolfy’s — now Rippy’s — on Lower Broadway. Later, when he lived in various locations in the downtown area, Lonow went to the cafe three to five times a week. Like many of us, sometimes he’d visit the restaurant known for its omelets, French toast, patty melts and plates of biscuits and gravy in the wee hours between last call and sunrise. But on one fateful New Year’s Eve while a couple dozen folks waited for a table in the parking lot of the packed diner, he had a momentary lapse in judgment: He crossed an invisible diner-etiquette force field by offering the cook $20 to bump his order ahead of others in line.

The cook obliged, but the server that night, a beloved veteran of the place who regulars called “Mama,” was not having it. “She literally never forgave me for that,” Lonow says. “She was disappointed that I had manipulated the system.”

That’s because according to “the system” at Hermitage Cafe, no one could buy their way to the front of the line. From city workers to firefighters, ravers, revelers, musicians, EMTs and bar backs, nobody ranked higher than anybody else, and everyone waited their turn.

“I think the cafe was one of those places where your class or your money or worth meant nothing to us,” says Sherri Taylor Callahan, owner of the cafe and daughter of its late founders. “You were treated by how you treated others.”

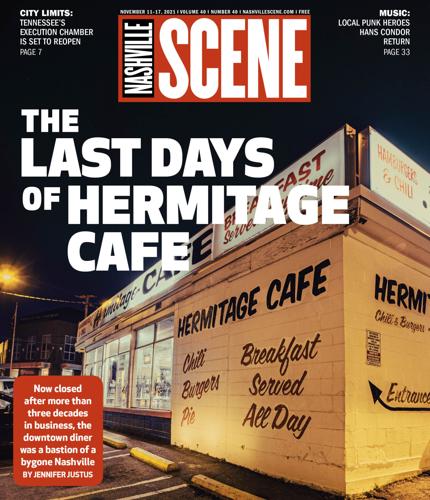

By the time you read this, Hermitage Cafe as we’ve known it will have been closed for more than a week. As Callahan notes, the landlord has sold the building, which for many years was a bastion of a bygone Nashville. For better or worse, that Nashville has largely been displaced or 86’d altogether — many of these shuttered establishments perhaps beloved less for their food than for the feeling they gave patrons.

Shields and Patricia Taylor

Shields and Patricia Taylor opened the cafe a little more than three decades ago, and it became like purgatory with coffee — a liminal spot between the party and home, or between home and work for the daywalkers. Though hours changed over the years (especially after Metro General Hospital moved from its location across the street near where the Ryman Lofts currently stand), the cafe operated most famously in the graveyard shift through lunch the following day — 10 p.m. until 1:30 p.m. For many, it served as a place for rest or restoration.

“You went to see everyone and make sure you could walk that extra block home,” says Booth Calder, a regular who lives nearby. “Put on some Merle Haggard,” she says of the legendary jukebox that used to spin 45s, “and two-step home with the street sweepers.”

Linda “Cissy” Siegrist worked at Hermitage Cafe with her mom Linda “Mama” Caldwell. They worked at the restaurant for 25 years apiece, with their tenures overlapping some in the middle — they served 15 years or so together on nights. “I loved working with my mom side by side,” Cissy says. Of the motley crew that traipsed in each evening, the mother and daughter had their favorites.

“All the bartenders and bar backs would treat her like a queen,” Cissy says of her mom. After closing down their own establishments, they came in for a bite and sometimes serenaded Mama with Merle Haggard’s “Mama Tried.” “That made me feel so good inside,” Cissy says.

And when a night shift would get rough? “They were your bouncer. They bused tables, served coffee, pitched in.” In turn, the Lindas and the rest of the Hermitage Cafe crew cared for their people — “as long as they behaved.”

Chark Kinsolving, former co-owner of Cannery Ballroom and its sister venues and current co-owner of Madison’s East Side Bowl, was a regular from the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s. He remembers Mama feeding him when he was broke. “I mean, completely broke,” he reiterates. “I actually traded Greg [a cook at the time] some kinda old 12-string acoustic guitar that had just been converted to six strings. Someone had stole his guitar, so I gave him that guitar and traded it out for a couple weeks’ worth of breakfast.”

The staff had a particularly shepherding eye for newcomers and lonely folks, like a 16-year-old who plays at Tootsie’s and visited the diner with his dad. In a demonstration of the cafe’s trademark tough love, Cissy promised his father to look after the teen or “kick his ass” if he got out of line. During the restaurant’s last week of service, Kim Allen — who came in as a partner at Hermitage Cafe seven years ago — received a message from a man she made feel at home after he’d packed up his guitars and moved to Nashville on a whim the day after Thanksgiving a couple years back. “You have fed me when I didn’t have money,” he wrote, “let me in before you were open (and stay after you closed), you even loaned me money when I was in a tough spot.”

Cissy remembers a homeless man named Darryl who Mama treated to breakfast with her tip money on occasion. He’d also sometimes sweep the floors for cash. After an attempted robbery when someone held a knife to Mama’s throat, Cissy says, Darryl slept in the parking lot for more than a week to keep guard.

As I was reporting this story, I started to get the feeling we could fill an entire issue with anecdotes about this kind of reciprocal generosity. Hermitage Cafe, its employees and we patrons may all have been imperfect, a little worn down at times. But maybe this is what hospitality looks like in its purest form — when folks are so dedicated to taking care of one another that the line between guest and host begins to blur. Sometimes grace is delivered scrambled or over-easy with a clank on the counter from a hard plastic plate.

Of course, there were limits to the staff’s patience with customers. If her mother caught you driving up drunk, Cissy says, “She would cuss you out and take your keys.” She’d demand you sleep it off a while before ordering.

Kinsolving recalls the time a man discharged himself from the hospital for breakfast. “He’d torn the IV out of his arm,” he says. “He was in his gown with his ass hanging out. He’s bleeding out of his arm and bleeding out of his face. Linda’s like, ‘You gotta get out of here.’ ”

There was also the night someone ran their vehicle into the building. I ask Kinsolving if he was there when it happened. “Yeah, it wasn’t my table,” he says nonchalantly, though that reminds him about the bullet holes in one of the windows and the booth beside it. He and his friends call that one the “Bullet Hole Booth,” fittingly.

Even with all that character, Kinsolving calls the place a safe haven. “I have this great, big, warm collective good memory that I can’t really describe,” he says. After he opened Mercy Lounge a mile to the west in 2003, he sent bands to the cafe for late dinner. “At that point in time, ‘the Herm’ was the only place to go unless you got on the interstate and found Waffle House. So we’d always send bands over there. … When I was running the Cannery, I took the Drive-By Truckers to the Herm one night.” Patterson Hood had a fried bologna sandwich, he says.

There is of course a long list of names of musicians who visited for photo shoots (Dolly Parton, Mindy Smith and Allison Moorer among them), videos (Jack White, Rascal Flatts) and release parties. It wasn’t uncommon to spot other celebrities there too, like legendary late Titans quarterback Steve McNair, who lived nearby.

But the staff wasn’t just fond of the night owls. Customers who came in at sunrise were favorites too. Hermitage Cafe owner Callahan was partial to a man she called Mr. Horace, who worked at the lunch counter in the Greyhound bus station and later elsewhere in food service. He told her stories about the civil rights movement.

Callahan’s family moved to Nashville from Chicago when she was 12 years old. Both her parents worked in diners their entire lives — she tells the Scene that her father Shields stood on a milk crate to flip burgers as a young boy, and her mother Patricia worked in her parents’ Chicago diner The Ducky Wucky. They opened the Hermitage Cafe space in 1990 after its brief tenure as a Vietnamese restaurant. (Before that, since 1954, it had been a Burger Boy.) “He put in the counters and everything by hand,” Callahan says of her father, who has since died. Her mother passed away seven years ago last month. Both Callahan and her late brother worked at the restaurant on and off as well.

As Nashvillians are all too aware, things change, eras end, people pass away and businesses close. In 2014, Mama left the diner following a cancer diagnosis, and she died in December of last year. Other beloved employees have moved on — like Doug, who folks called “Frenchie” because of his chef’s hat. Others, meanwhile, stayed until the bitter end — including Tina, who cooked at the restaurant for two decades, as well as Kim Allen and her partner Richard. The couple plans to open a food truck called Cussin’ and Cookin’ With Oswall (Richard’s nickname) as well as a souvenir truck in the parking lot next to The Batter’s Box nearby.

After Hermitage Cafe’s final service, Kim stood out front letting folks know they’d run out of food. It seemed somehow appropriate that the diner closed one shift earlier than expected. Cissy wasn’t planning on being there anyway. “I had to get away because it was so sad,” she later tells the Scene by phone. “That’s pretty much basically my life, my family. That’s the only thing I had left of my mom.”

But even as Kim cleaned up and took decorations off the wall, a regular named Stanley Peacher stopped by. A customer for 21 years who works nights for Metro Water, he had an off-menu item named for him — “The Stanley,” eggs with chicken, bacon and veggies. Where will he go now? “The only other place I know is, like, Wendy’s,” he says.

Others also stopped by to pay their respects, including Emily Goncalves and Jennifer Tat, who moved to Nashville to attend Vanderbilt University just a few years ago. They’d read about the diner and wanted to visit for a “first, last time.” Goncalves, after all, recognized the tenuous nature of a mom-and-pop establishment in a place like Nashville. She was a fan of J&J’s Market, which closed three years ago and was later bulldozed. “It’s a piece of history that’s closing,” Tat adds.

But just shy of 11 p.m. on Halloween — a time of night that used to feel so early at this place — it was just too late.