On any given day, Bianca Morton-Hughes might get to work and have something outrageous waiting for her — like 1,000 pounds of fresh asparagus, or enough meat to stock her walk-in freezer for a year.

Morton-Hughes is the chef director at The Nashville Food Project, a nonprofit that makes 5,000 nutritious meals every week for Nashvillians in need. That half-ton of asparagus was donated by Walmart, and it was perfectly fresh. So that week, everybody had some. “You got asparagus-and-egg casseroles,” says Morton-Hughes, “you got asparagus-and-vegetable blends, you got asparagus that was pureed to add into sauces, you got asparagus vinaigrette. … Stir-fries, vegetable medleys, cut them up, add them to pasta salad. We were going to get as many uses in different ways as we could.”

Typically, The Nashville Food Project marshals about 380 volunteers per month to collect food from gardens, conference centers, farms and stores. Under Morton-Hughes’ direction, the volunteers prepare meals from scratch that are tailored to 35-plus partnering organizations, and they load them into catering trucks for delivery. During the pandemic, they suspended their volunteer program, leaving all of that work to the staff. But the need for food didn’t slow, and the Food Project has continued to provide.

Bianca Morton-Hughes

The efficacy of the organization can be attributed in part to its practicality. The Food Project partners with anti-poverty organizations across the county, like Open Table Nashville, Gideon’s Army and Project Return. Whether these organizations are fighting poverty, interrupting violence or supporting people after incarceration, they’re the ones who know their communities best. The organization keeps upward of 220,000 pounds of food out of landfills each year. You can also look at food recovery as a manifestation of the Food Project’s ethos: There is plenty to go around, and when we work together, we find that there are many more seats at the table.

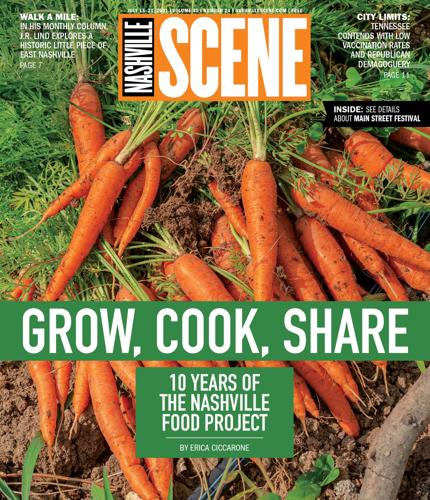

This belief has been the guiding force behind The Nashville Food Project since its inception a decade ago. The organization’s founder, Tallu Schuyler Quinn, had a radical vision of a movement that would not just provide emergency relief to hungry people, but also connect people to food systems and the land in order to remove barriers that keep them undernourished and underfed. As the nonprofit celebrates 10 years of growing food, making meals and sharing them, the Food Project community is experiencing a devastating crisis. One year ago, at age 40, Quinn was diagnosed with grade four glioblastoma, an aggressive, terminal form of brain cancer.

Quinn grew up in Nashville. After getting a bachelor’s degree in papermaking and bookbinding, she headed to seminary at Columbia University. With a Master of Divinity degree, she went to Nicaragua, where she worked on food-security projects with resident farmers. It was there that she started to see food differently: not as a commodity, but as a “vibrant tool for healing.”

“Living in Nicaragua, where food was very scarce and very much part of a whole community’s cultural identity,” says Quinn, “I think I got the privilege of getting this peek into how sacred food can be and what a powerful tool for good things it can be. It’s been very much weaponized in the way it is unaffordable or inaccessible.”

When Quinn came back to Nashville, she started working with the local chapter of the national nonprofit Mobile Loaves & Fishes, handing out sack lunches and bottles of water at places in town where people without housing congregated. Emergency food systems like this have their place — often, that’s all that’s available for hungry people. But Quinn saw the need for something greater that could break the cycle and change the story.

“My hopes and dreams for Nashville were building and finding people to be part of a movement that really could build community and focus on different expressions of justice — economic justice, food justice, racial reconciliation and racial justice.

“We certainly didn’t invent food accompanying the creation of community,” she continues. “That’s ages old. … But to be able to find community, period, is so special. To be able to find really awesome food alongside that, especially if you’re living in poverty or have a lot of challenges around accessing adequate nutrition, is so important.”

In 2010, Grace Biggs — then a student at Lipscomb University — met with Quinn while doing some research for her senior capstone project. That conversation turned into an internship with Mobile Loaves & Fishes. Biggs was tasked with picking up food at Sam’s Club and slicing bread for sandwiches. Working out of Woodmont Christian Church, the nonprofit relied on volunteers to deliver meals in the city.

Biggs says Quinn was already asking questions that would deepen their work. People most impacted by food insecurity and poverty needed to be part of creating solutions, Quinn maintained. She wanted to create long-term partnerships, not just one-off interactions. “Just handing out meals endlessly,” says Biggs, “you could do that forever and not solve any of these issues. So how can we best align the resource of a meal with other anti-poverty and community-building work happening in the city?”

Left: Tallu Schuyler Quinn in 2013

Right: Grace Biggs

In the three weeks following Nashville’s historic May 2010 flood, the team distributed more than 19,000 meals to displaced residents and relief workers. They started a garden behind their office at Woodmont Christian Church, and Quinn met with everyone who would give her a meeting to garner support. She wanted to differentiate what she was doing from food banks and pantries. “I don’t really believe in banking food,” says Quinn. “Why hang onto all this nourishment when so many people lack?”

In 2011, Quinn established The Nashville Food Project as a nonprofit, and Biggs stuck with her as an employee. They started converting those sack lunches to hot meals made from scratch that could be served family-style. “We were so scrappy and really under-resourced and didn’t have land,” says Quinn. “But so many people started to step up to the plate with the very generous resources of time and insight and money and really good questions and guidance for me and other staff as we were able to hire people on, which was very slow-moving.”

Establishing the nonprofit legitimized what they were doing, and it helped them launch an agricultural program. The Woodmont garden grew food for the kitchen — but from her experience in Nicaragua, Quinn suspected that giving people the opportunity to connect to the land and grow food for their families themselves would provide empowerment. Over time, they opened gardens in places around the city and put the word out that they were available for community gardeners. By meeting twice a month as a group for lessons in planting, growing and harvesting organically — and with access to their plots any time during the growing season — gardeners got their hands into the soil.

In 2019, the Food Project got the opportunity to steward a new garden on the site of the future Mill Ridge Park in Antioch. Metro broke ground on the land in June of this year, and the 600-plus acres will be a welcome recreation and conservation space in a part of the city that has lacked public greenspace for decades. The Community Farm at Mill Ridge is three acres for now, and the Food Project will have the opportunity to expand as it builds capacity. Community gardeners have plots — some individual and some communal. Renting a plot for a year costs just $15-$30, depending on the size, and the Food Project is able to accept SNAP for plant sales each spring. Twelve-foot sunflowers grow across from the shaded pavilion. Gardeners are growing tomatoes, squash, sweet potatoes, pumpkins and much more.

“There are so many stories and histories in this garden,” says Lauren Bailey, director of garden programs. Some people are totally new to gardening, while others connect to their agricultural roots. It’s especially beneficial to people who rent their homes and don’t have a plot of land they can alter with flowers and vegetables. But one thing unites them, says Bailey: they’re “lots of people who love digging their fingers in the dirt.”

Another arm of the Food Project’s agricultural program is Growing Together, a market garden program that supports people who want to sell produce for income and to connect more deeply to food systems. The program currently supports farmers who arrived in the U.S. as refugees from Myanmar (formerly Burma) and Bhutan. At the Haywood Lane Farm, the Growing Together farmers grow enough to sell via community-supported agriculture — which is like a subscription service of fresh veggies — and sometimes also sell to restaurants and to the Food Project for meals.

Growing Together farmers Lal Subba (left) and Dim Pau

Lulu Nhkum helps her mother-in-law tend to her plot and also acts as the interpreter for the gardeners and Growing Together manager Tallahassee May. Nhkum and her family are growing greens, radishes, gourds, pumpkins, cucumbers, eggplant and more. Nhkum comes from a family of farmers, although it is increasingly difficult for her parents, who still live in Myanmar, to grow crops because of the increasingly violent military coup.

The vegetables that are grown in Myanmar and Bhutan are hard to find in Nashville, so growing them gives these farmers a taste of home. Of the program, Nhkum says: “It helps our mental health — makes us whole. It’s our workspace. It’s no pressure. We can learn a lot, and we can grow any kinds of vegetables that we like. If we don’t know [something], we can ask. This has changed our life.”

The garden is a haven for Nhkum, and her family is financially supported by the sale of their vegetables. Her 5-year-old son David is on site when the Scene visits, and he bounds around with his grandmother, playing and helping with the harvest. Nhkum says that sharing the space has made her son more willing to try vegetables than he used to be. Many of the farmers are in their 60s, and part of their vision is to get younger people like David involved to carry on their agricultural traditions.

“Everything is possible,” says Nkhum. “It’s amazing.”

As the Food Project evolved, it grew out of its home at Woodmont Christian Church, using a kitchen at St. Luke’s Community House. But as their partnerships and their staff increased, they needed their own home. In 2017, Quinn spearheaded a $5 million capital campaign for the construction of a headquarters with a large commercial production kitchen, offices, a community dining room and meeting rooms. Located on California Avenue in The Nations, the space is gorgeous and airy, and the state-of-the-art kitchen gives Chef Morton-Hughes plenty of room to play.

After culinary school, Morton-Hughes did what she calls a rite of passage for Nashville chefs: She worked at the Opryland Resort & Convention Center. For nearly two decades, she worked in high-capacity, high-quality catering kitchens — as the executive sous chef at the Sheraton downtown, as part of the opening team at the Music City Center and more. That was her dream, but she felt unfulfilled. Three years ago, she arrived at The Nashville Food Project.

“I felt like I was at home,” Morton-Hughes says. “I realized that I’ve always been the type of chef that, what I do, I [form] a personal connection. So I love that the meals and the food that we’re crafting and we’re sharing, it’s thought put into it. It’s love.” This sentiment, of feeling at home and cared for within the organization, is common among employees. It’s one of the things that makes The Nashville Food Project so special.

During the Scene’s visit on a Friday, the kitchen team is packing up boxes of beef lo mein — the beef is from Porter Road Butcher, which donates 100 pounds of ground beef every week — for Open Table Nashville and New Immigrant Community Empowerment. Other meals of the day will go to the YMCA children’s summer camp, the Martha O’Bryan Center, Operation Standdown and 15 more partners.

Morton-Hughes is charged with tailoring meals to the partners, which is no easy task. As director of food access, Biggs receives feedback from the partners, which she relays to Morton-Hughes. The chef does her best to accommodate this feedback, while making use of whatever food ends up in her kitchen via donations. Some are unfathomably large — the day of Nashville’s March 2020 tornado, the Annual Meat Conference at Opryland had 28,000 pounds of fresh, never-frozen meat on their hands, and the folks at the Food Project took it. Recently, a first-grade class brought four little bags of lettuce they had grown, and backyard gardeners often donate bags of tomatoes.

“It’s like being on Chopped,” says Morton-Hughes. “Every single day.” She enjoys sharing knowledge about food and nutrition with partners, particularly those serving children. Vegetables can be a hard sell, especially ones like asparagus, and while the chef can “hide” them inside other foods, she wants kids to know what they’re eating.

Growing Together farmer Nar Guragai

“When you look at the kids that turn their nose up at anything other than some fast food,” says Morton-Hughes, “that’s where [food injustice is] showing up. We just don’t know better, and it’s become a norm. So when we’re trying to do this, we’re fighting against our own selves and our own beliefs.”

They have a saying, Quinn tells the Scene: “Cheap food hurts people.”

“Growing food cheaply on land and [continuing] environmental degradation comes back to hurt us in myriad ways,” says Quinn. “Cheap food that is sugar-laden and prepared with shitty ingredients, it hurts people in our physical diet. If we keep poisoning our earth to grow cheap strawberries, that’s going to come back and hurt us too.”

She uses Growing Together as an example. “It’s the opposite of cheap food, and it’s also the opposite of hurting communities. It’s power. It’s money. It’s reconnecting to the land. It’s reconnecting to one’s culture. It’s brilliant farmers having a path to reconnect to the work that they love, the work that they know, and to earn meaningful income while doing it to be able to grow food that is meaningful culturally to them, to share that knowledge with other farmers as well as their customer base who may or may not know about these specific mustard greens that come from Nepal, for example, and how to prepare them.”

From left: Nora McDonald, Lauren Bailey and Julia Reynolds Thompson at The Community Farm at Mill Ridge

Quinn stepped down from the role of CEO last summer when she got sick. Last week, the Food Project announced a new CEO, C.J. Sentell, whose experience in sustainable farming, nonprofit management and social entrepreneurship should prepare him to fill some very big shoes. He co-founded the Heifer USA Grass Roots Farmers’ Cooperative in Arkansas, where he explored the economic viability of cooperative farming and sustainable animal husbandry. He then worked at FORGE Community Loan Fund, focusing on helping economically disadvantaged people start and maintain agricultural businesses. His dissertation at Vanderbilt University traced the relationships between freedom and food through the intersection of slavery and agriculture. Like his predecessor, Sentell is passionate about creating food systems that work for everyone.

Despite visual and cognitive strain, Quinn has kept a public journal since she became ill. In writing, as in person, Quinn is wise, funny and brave. She posts poems by Wendell Berry and Mary Oliver, retells the story of how she met her husband Robbie, and professes her admiration for Nora Ephron and the Indigo Girls — she’s seen the group in concert 50-plus times, she says. She also grieves the life she will soon leave behind. The long-term life expectancy for patients with glioblastoma is three to five years, but many people die much sooner. “Life,” she wrote in a May journal entry, “will dash and devastate, all while handing you a damn dream come true.”

Her clear-eyed optimism and her belief in this work have not dimmed. Quinn says of The Nashville Food Project: “I want us, as we move forward into the future, to be emboldened by constantly pursuing what we know we’re here to do. And what we’re here to do is constantly show up in active ways for people who are oppressed, for people who do not have power, and not to give them power, but to uncover whatever barriers or shackles are in the way that keeps us from being the just society that we are here to be.”

Biggs has spent the past 11 years helping the organization to grow and thrive, and she’s one of many. It’s a difficult time, but she too is hopeful. “The heart of the Food Project is the same,” says Biggs. “There are new faces and different people. I still very much feel and see Tallu’s legacy and mark on the ways we are moving forward together.”

It’s like Quinn tells the Scene: “A place to belong in this broken world is pretty much everything.”