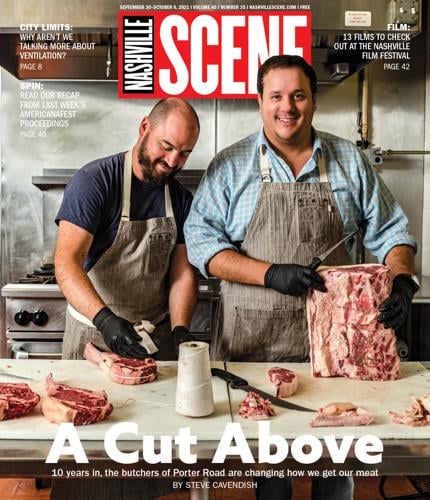

Chris Carter (left) and James Peisker

To understand the relationship at the heart of Porter Road Meats, the Nashville butcher shop that’s become an internet success story, you first have to understand that a business partnership can be a lot like a marriage. There are highs, there are lows, and there are things that partners share that almost no one else can understand. And in the fall of 2016, the partnership between Chris Carter and James Peisker was leaning toward a divorce.

Over the course of the previous five years, the duo had built Porter Road from a farmers market operation — where they bought one cow at a time and sold the cuts piecemeal — into a thriving retail and wholesale operation with shops in both East and West Nashville. They had become friends in restaurant kitchens and shared a passion for butchering, and earnestly wanted to change the way Nashvillians think about meat. Working with farmers, they gradually built a supply of high-quality products without many of the issues plaguing industrial meat providers: antibiotics and hormones in the animals, inhumane conditions and a boom-bust cycle for the humans tasked with raising them.

“Our health will change if we change what we eat,” Peisker told the Scene in 2012, months after opening the initial shop on Gallatin Pike.

But fast-forward to 2016, and much of Carter and Peisker’s enthusiasm was drowned out by the problems of their growth. Porter Road had gone from being a couple of butchers with a vision to a business struggling to keep good employees. At the store on Charlotte Avenue — a converted Mrs. Winner’s — the pair had visions of building breakfast clients with sausage biscuits and sweet rolls in the mornings while selling their favorite cuts of meat all day.

And for a while, it worked. But a revolving door of cooks, counter help and meat cutters (restaurants hired away some of their best butchers) often had them working 5 a.m. shifts just to keep the operation moving. The purchase of a processing facility in Princeton, Ky., in 2015 had given them the control they wanted over their meat, but it also meant another management headache — one located 100 miles away.

The lowest point came in November 2016.

Carter and Peisker had closed Porter Road’s West Nashville shop at the end of October, tired of the headaches and the drag on quality. But rather than celebrate the sale of the building to Fresh Hospitality for Pat Martin’s new burger concept Hugh Baby’s, the pair headed up to Princeton for deer season. It was a holdover from the previous ownership of the processing facility that Porter Road simply couldn’t afford to ignore: Almost a third of the income for the year at the facility came from processing the kills of local hunters. So the pair lived in the back of a 1970s-era camper behind the slaughterhouse for most of the month, working 90-hour weeks to service hunters and keep the supply going to the Gallatin Pike location.

“I slept in the little area [where] you would be above the actual truck,” Peisker says. “Chris slept down low. There was a 30-degree temperature difference between where he slept and where I slept.”

“You could put your arm up and feel it — it was like the equator,” Carter says about the propane heat, which kept them from freezing. It was their second deer season and not fun. (Side note: When guys who butcher animals tell you cutting up a deer is “gross,” you tend to believe them.) Carter shared his bunk with his 100-plus-pound dog, and at some point the living conditions just got the better of him.

“Chris was out of it because he couldn’t get the door to open one day,” Peisker says. “So, he’s sleeping — or not sleeping — and it’s boiling hot and he’s sharing the space with his mastiff Marley. He was just like, ‘Fuck, I got to get out of here.’ ”

“Oh yeah,” Carter replies. “I had to get out the door. I was having a huge panic attack.” To top it all off, Peisker told him that he might be moving to Chicago. Peisker and his wife Marta had moved to Nashville so that she could get a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from Vanderbilt. But she completed her studies and the city didn’t have an appropriate job for her, so Marta was spending her days as the most overqualified counter clerk at Porter Road’s shop.

“James told me he was moving to Chicago,” says Carter. “And we literally said, ‘Well, I don’t want to do this without you.’ ”

That could have been it. After deer season ended, the holidays ramped up and Porter Road was inundated with requests for the holiday favorites, mostly tenderloins and roasts. For an operation that had been devoted to whole-animal butchery and leaving nothing to waste, December left them with great cuts of meat that were sold off cheaply or, worse, ended up in ground beef.

“We had the largest Christmas in 2016,” Peisker says. “That year, I was up on the ladders harvesting tenderloins out of hanging carcasses while Chris was holding either the carcass or the ladder. I don’t really know at that point because we were half-dead. We literally took a saw and cut out rib roasts from carcasses hanging. And we were like, ‘We’ll deal with the rest of the animal later.’ Before the New Year, [Carter is] going through talking to his friend, this gentleman named Ryan Darnell, and they’re video phoning. He’s walking through our cooler saying, ‘Look at all these amazing cuts.’ Teres majors, picanhas, flat-irons, bavettes. All of these steaks that we can’t keep in stock anymore. We just had mountains of them because all people wanted during Christmas was tenderloin and the rib-eye. And we were like, ‘There has to be a better way, there has to be a better way.’ Our favorite parts of the animal were just getting sold off at discount to our lucky friends that own restaurants.”

Darnell, by quirk of fate, had shared a spot on the defensive line with Carter at Hendersonville High. After playing baseball at MTSU, Darnell got an MBA at Vanderbilt before heading off to New York in pursuit of a career in finance. As it happened, Carter had been talking with Darnell for months, bouncing ideas off of his friend-turned-venture-capitalist during the commute between Princeton and Nashville.

“I didn’t know what a venture capitalist was, but I knew that Ryan Darnell had become one,” Carter says, half joking. “And that he had money to get people to grow their business. And then about three weeks later I came in and told James, ‘What do you think about launching a website? You can work remote, and come in and run the facility. We’re going to raise money. We’re going to build an incredible business. And won’t have to be buried in the facility at all times.” ’

From a hectic deer season that almost broke them, porterroad.com was born.

The beef industry in the United States looks like an hourglass.

At the top are more than 900,000 farms and ranches of all shapes and sizes, growing the livestock that we consume. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, those farms and ranches (farms in the east, ranches in the west) produced 27.2 billion pounds of beef in 2019.

On the bottom are nearly 40,000 retail outlets, more than a million restaurants (pre-COVID) and 328 million or so American consumers. All told, we ate about 218 pounds of meat per person in 2019 — an astonishing number when you consider that Gallup says the average American weighs 181 pounds. If you consider the fact that 5 percent of the U.S. is vegetarian, we’re probably well north of 225 pounds per meat-eating American. (That includes 56.8 pounds of beef, 51 pounds of pork and 92 pounds of chicken per person.)

But in the middle of that hourglass are the packers, the sector that turns those heads of cattle into the cuts that appear in the refrigerated section of the grocery store, ground beef for your favorite fast food joint’s burger and everything in between. Just four meat-packers — Tyson, Cargill, JBS and National Beef Packing — make up about 70 percent of total U.S. beef production. And that’s where many of Big Meat’s problems lie.

During the pandemic, when supply chains were disrupted and virus outbreaks plagued the large meat-processing facilities, the Big Four were accused of price gouging. Nineteen senators and 11 attorneys general urged the USDA to investigate the giants. Smaller ranchers complain that they are being crushed by the Big Four, while consumers and regulators say that the average price per pound of beef has remained artificially high.

If the economics weren’t controversial enough, critics of factory farming argue that abuses can be found across all areas of production, from poor conditions for animals in feedlots to poor working environments for plant workers. It’s enough to put some people off meat, and it in part explains the explosion in popularity of plant-based substitutes like Impossible Foods in recent years.

For the most part, Carter and Peisker agree with the critiques of the industry, and those critiques guided their approach to meat.

“So feedlot beef are fed a diet to where they’re almost going to keel over and die because it’s so unnatural ... but they fatten up and they grow really fast,” Carter says. “So they’re fed antibiotics to make sure that they’re healthy and they stay alive. What we try to do is give them a more natural diet to where they’re still healthy, they don’t need the drugs, they’re given space to run around and go, but they fatten out. Because that finish is what we’re looking after too. Because Porter Road was originally started in the search of that perfect steak, in search of finding that flavor. And along the way, we found that if you take care of the animal and take care of the land while you’re doing that, flavor comes as a reward.”

Developing relationships with farmers has been crucial to Porter Road’s response to factory meat. Over the years, Carter and Peisker were able to set standards for animal care, including prohibiting the use of antibiotics, hormones and steroids. That resulted in not only better living conditions for cows, pigs and chickens, but also in price surety for producers. Porter Road has paid, according to Carter, a 20 to 40 percent premium to farmers for the final product, a figure set well in advance. But because they’re processing entire animals and not just taking the best cuts, there’s less waste. And for their farmers, uncertainty created by the roller-coaster world of commodity prices has been cut dramatically.

“It’s a relationship that we’re building, and that relationship is about trust because our consumers trust us that we’re doing the work to make sure that we’re selling the products that we are,” Peisker says. “We really want to make sure that we’re being truthful with our actions. And that’s [why we’re] making sure that we’re doing those audits, making sure that we’re going to the farms, making sure that [farmers are] adhering to the standards and then double-checking them. We can double-check them when the animals get to the slaughterhouse. We can double-check them when we go out to the farms. We do surprise visits. We send other people there.”

That emphasis from the field to the final product set Porter Road apart in the eyes of investors. If controlling the whole process had been what Peisker and Carter originally sought in order to get a better, more humane product, it also left them with advantages that became apparent quickly to Darnell, whose job is to sift through companies and find what makes them a unique opportunity.

“We got into ‘What if you guys went from being just a single store in Nashville and trying to build a national brand?’ ” Darnell says. “That’s a much different business than, obviously, trying to have a local butcher store. It’s a big shift in mindset too, because you’re not going to raise venture capital and be small. You’re going to really go for it. You’re going to try to have hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue instead of a million dollars in revenue. I think we went on this three-month exploratory adventure together to figure out: 1) if it’s something they wanted to do, 2) is it viable and 3) in bringing in a lot of outside capital and building a real team, did they need help? They needed help understanding the direct-to-consumer world.”

To enter the venture capital world, Peisker and Carter would have to go to New York — something Carter had never done. It was a long way from starting Porter Road with just $500 between the two. Darnell arranged a series of meetings with prospective investors.

“I kind of wanted to throw them in the deep end with some of the most legit people in the world, and let’s see what happens,” Darnell says. “And one of our early design partners [Red Antler], who has been one of the most successful design partners with startups in the world, was I think their first meeting. It was a huge meeting, and they just raved about the product. And the thing that they saw was, a lot of times you get a lot of Harvard business school grads who come in and say, ‘Hey, here’s this white space in meats ... here’s how big the market is.’ And they don’t really know, they’re not really the authentic person.”

Over the course of a relentless set of 30-minute pitches, the trio found traction. Even when they didn’t find investors, people were impressed by Carter and Peisker’s knowledge of the meat industry, and Porter Road’s story had resonance. Eventually a couple of top early-stage digital commerce investors climbed on board.

“I think we left New York and it went well,” Darnell says. “Chris and James are smart guys. They know how to adapt and quickly learn. So they did that, and they made the commitment like, ‘Hey, we’re all in here, if you want to do it with us.’ And I said, ‘If you’re all in, I’m all in.’ So we kind of got our act together, we made some key hires that would help them understand how to operate a digital business, how to build out the digital infrastructure, how to basically build an online brand that has no physical real estate.”

On a scorching day in early July of this year, Carter and Peisker stand in front of a 28,000-square-foot white building in Princeton, Ky. A host of dignitaries including that city’s mayor, two state representatives, a state senator and the lieutenant governor have showed up to cut a ribbon on Porter Road’s new processing facility. The Princeton Fire Department’s Ladder No. 2 truck is decked out with a giant American flag waving high over two tents full of locals enjoying hot dogs and hamburgers.

“This is a big deal, not just for the community, but for the region,” says Lt. Gov. Jacqueline Coleman. After being elected in 2019, she pledged to concentrate on rural workforce development, and this expansion certainly qualifies. By the time it’s fully operational, Porter Road will add 60 jobs to the 40 already in place, making them the third-largest employer in town.

Peisker sounds like he might be campaigning for something himself (he’s not) as he explains how one pig led to two and then four and then more and more as the company grew.

“There’s a broken system,” he says. “And it is broken for all the farmers who put in all the hard work.”

The pair lead groups through the new facility, pointing out all the small touches that were made with employees in mind: The break room is one of the biggest rooms outside of the cold warehouse, with a TV on the wall; locker rooms were designed for ease of use; the office workers who sat almost on top of each other at the old facility now have their own spaces. In the shipping facility — an area as big as the entire processing plant they moved from — rolling racks are designed to minimize the twisting motion that can lead to back problems. It’s hard to believe this building previously housed a big illegal marijuana grow operation — something that’s not in the talking points of the local dignitaries.

While the crowd is focused on the festivities of the day, Carter is already looking ahead at the next expansion. He signed a deal to buy their next building in Princeton just before the start of the ceremony.

All of this is possible for two reasons: First, porterroad.com has had huge success since its launch in 2018, with the business growing more than 10 times by the end of 2020. And second, the company closed on its second major round of funding, raising $10 million from a variety of funders in order to fuel that growth.

During their initial trip to New York, Darnell introduced Peisker and Carter to Ryan McIntyre, who would eventually run Porter Road’s digital side. McIntyre’s only experience with meat was “that I really liked it,” he tells the Scene with a laugh. But he realized that Porter Road was arriving at an interesting time in e-commerce. Fascinated by the company’s story, he spent much of 2017 going through all of the processes it would take to turn porterroad.com into the kind of experience Carter and Peisker sought to create in the Gallatin Road shop years before, from packaging to cloud-based inventory to checkout.

Key to their success would be Shopify, one of a newer series of consumer platforms that was democratizing e-commerce for small businesses. McIntyre estimates that just a few years ago, Porter Road would have had to maintain a payroll of developers in the neighborhood of $50,000 per month instead of paying a couple thousand for an off-the-shelf solution.

At the same time, Porter Road had to begin finding digital customers. Good word-of-mouth gave them a strong base of support, but in order to grow, they would have to employ a range of marketing, from email to something as old-school as direct mail. They’ve been aggressive about taking advantage of Peisker’s relative ease in front of a camera, featuring him heavily in the brand’s Instagram feed as well as partnering him with various YouTube channels for cooking and barbecue shows. One half-hour episode of Binging With Babish, a popular culinary show, features Peisker cooking every cut of meat in Porter Road’s lineup. As of press time it has more than 3.3 million views.

Over the past three years, Porter Road has morphed from an East Nashville butcher shop to a direct-to-consumer meat provider shipping to every one of the lower 48 states. The site thrived during COVID — so much so that McIntyre says they had to remind customers not to panic buy, like many retail grocers were experiencing.

Says McIntyre: “We actually sent a letter to our customers via email, no links in it whatsoever, and it was like: ‘We get it. It’s a really weird time. We’re not going anywhere. We’re isolated here in western Kentucky. We don’t expect any disruptions to our supply chains just given how insular our supply chains are. You don’t need to panic buy.’ And I think it was one of the more productive sales emails we ever sent. We’re like, ‘Well, that wasn’t the intent.’ We wanted to have just a, ‘It’s going to be OK everybody’ [message], but boy oh boy, did people end up coming around the edges and buying from that email. But OK, we very quickly hit the production capacity cap out of the old facility.”’

In fact, McIntyre adds, Porter Road had to actually dial back its marketing.

The pandemic also helped Porter Road complete the transition mostly out of the wholesale market. Where restaurants once made up more than half of their business, now it’s just a couple of select clients with the rest sold at retail.

Nine years ago, an idealistic Carter and Peisker told me they wanted to change how Nashville consumed meat. It was the kind of statement you chalk up to enthusiasm and a little naivete, the words of a couple of guys who really wanted to do something different. In the wrong light, it could be considered hubris. But from two guys who really loved what they were doing — they once rolled an in-use smoker down Gallatin Road to their favorite bar with a police escort — it comes across as straightforward passion.

As the company turns 10 later this fall, they may actually be building something special. Consider the hourglass that represents beef production in the U.S. right now. Is Porter Road going to unseat Cargill or any of the Big Four that control 70 percent of beef production? No, not even close. But what happens if an upstart like Porter Road, dedicated to humane practices and better meat, were to capture just 1 percent of U.S. beef?

It’s a prospect enticing enough to attract Bill Rupp to join the Porter Road board this month. In 2016, Rupp retired as president of JBS, one of the Big Four. Before that, he had been president of Cargill. He’s spent an entire career on the side of Big Meat, but he sees something in Porter Road that could be different. He talks glowingly about their dry-aging process and how it gives them an advantage over others.

“You know, we talk about the dream being, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool to take this business to be 1 percent of the annual beef harvest in the U.S.?’ ” says Rupp. “And today that’s probably round numbers — 26 million cattle get harvested a year in the U.S. So 1 percent of that’s 260,000 head, which is a long ways from where they’re at today. But if you think about that, if you’re talking about 1 percent of the supply, you’re really talking about 1 percent of the demand too. I think there’s a trend among consumers today where they want to understand more and more where their meat came from. They want to make sure that the supply chain is transparent. They don’t necessarily want to know every detail, but they want it to be there if they do. And so I think that kind of consumer that I just described is a growing segment of consumers. And I think it’s more than 1 percent today. And then I think you marry that with a consumer that just wants an outstanding eating experience, and that fits Porter Road as well.”

One percent would make Porter Road a $600 million business. It’s something that excites Randall Ussery, whose L37 firm led the latest round of funding. He says the ripple effects from the success of someone small could bring real change to an industry that could use it.

“If you think about Ben & Jerry’s, everyone said they couldn’t do what they did from a supply-chain perspective,” Ussery says. “They couldn’t bring in the best ingredients, hire the best employees, do all these sorts of things, because ice cream’s a commodity. Well, your food should not be a commodity. It should be something you really love and enjoy, but it shouldn’t be at a price that’s so exorbitant that everyone around you can’t have it. And these guys have the ability to bring pricing down, to make a small bite, just 1 percent in the industry that will end up having lasting effects from perception in the industry. We do think it’s a very large play, but it could also have a massive impact on an industry that needs help right now.”

It’s not something that could happen in a year. But in 10, or 20? Maybe. Not bad for a couple of guys who could barely afford to buy a single cow a decade ago.

James Peisker (left) and Chris Carter