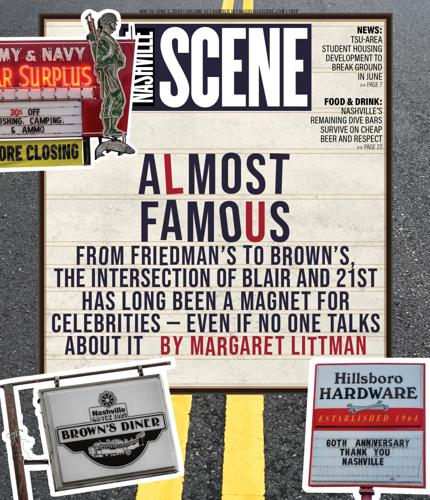

When visitors come to town and ask where the famous people hang out, no one ever says, “the intersection of Blair Boulevard and 21st Avenue South.” When you read lists of where celebrities shop, you might see spots in 12South, Green Hills or maybe East Nashville. No one says “Blair and 21st.”

But they probably should. When 22-time Grammy winner (and Eagles member) Vince Gill recently TV-toured a crew from This Old House around town, he took them to get a burger at Brown’s Diner. Back when publishing houses used Rolodexes and songwriters didn’t have cellphones, BMI had a typewritten Rolodex card with John Prine’s address and phone number. Handwritten on the bottom was an alternative number to reach him: 615-269-5509. That’s the phone number for Brown’s.

On one of the most exciting days I experienced at Friedman’s Army Navy Outdoor Store — where I worked as a college student — I sold a pair of jeans to Marie Osmond. (Be still, my “Paper Roses” heart.) She tried them on in the flimsy wood-paneled dressing rooms next to the shoe department. This was in the days long before Imogene + Willie or High Class Hillbilly. Friedman’s was the place to buy denim.

Friedman’s, located next door to Brown’s Diner underneath Doric Lodge 732, has served plenty of other celebrities too. That’s according to Frank Friedman, the store’s second-generation owner. He remembers when Miranda Lambert and Blake Shelton (then still a country music power couple) came into the store, and Friedman’s dad gave them a high-pressure sales job, not knowing who they were. (They did not leave empty-handed.) Connie Smith and Marty Stuart (another country music power couple) have shopped often at Friedman’s too. Gill remembers stopping in (after his Brown’s burger) to buy fishing lures, flannel shirts and knives.

“Because of the Nashville it was back then, you saw somebody [famous], you could say, ‘I appreciate your work,’ and go back to your business,” Friedman says. “They could come to Friedman’s and wouldn’t be bothered. I’m not sure that exists anywhere anymore.”

Like nearly every other intersection in Nashville, things are changing at Blair and 21st. In January, Friedman announced that he and his wife Mimi were ready to retire. The store is closing in June, and all remaining inventory is on sale.

“The fact of the matter is, we’ve been in business for 75 years, and it’s just our time to go,” Friedman says. “I’m ready.” His parents opened the business in 1949 and ran it until 1989, when he took over. While the retail landscape, the neighborhood, the city and store inventory have changed over the past three-quarters of a century, Friedman stresses that it’s not e-commerce or developers or any other external forces leading to the store’s closure. He and his wife have two daughters who have different careers.

The building, which once was home to a Kroger grocery store, is owned by the Free and Accepted Masons, which has regular programming upstairs. They will continue to be the landlords for the 8,500-square-foot space currently occupied by Friedman’s. A new tenant has not been announced.

Friedman’s Army Navy Outdoor Store

With Friedman’s closing, Nashville is not just losing a supplier of Osmond-worthy jeans, Duck Head chinos, ammo and fishing supplies. It’s losing the kind of everything-you-didn’t-know-you-wanted store, where serendipity reigned.

Kate Mills, a former Nashville designer known for her ability to craft statement pieces out of unusual objects, was a Friedman’s devotee. When she and her husband relocated to Maine, she found many items that came from Friedman’s as she unpacked: a silver astronaut-esque jacket, scarves, enamel pins and other “random treasures.”

Muddy Roots Festival organizer Jason Galaz bought World War II-era bunks that he used in an underground record shop he called The Vinyl Bunker. Other Nashvillians recount buying Girl Scout and Boy Scout supplies there. A first pair of fatigues. Colored bandannas. Overalls used for a significant painting project.

But it wasn’t just about the random goodness on the shelves. Part of the magic was the fact that staff was trained in an old-school approach to selling; they knew about the inventory and could make recommendations based on customer needs. Well, perhaps not the temporary college student-employees selling jeans and sweaters, like me. But the rest of the staff worked at Friedman’s for decades. They knew their stuff.

“One time a customer came in and said, ‘Thank God!’” Friedman remembers. “‘I went to Bass Pro. I looked around. Nobody was there to help me. I went to Dick’s — couldn’t find anyone. I walked out and said, I’m going to Friedman’s!’’’

Friedman’s has a history of adapting to its customers’ needs.

“Before credit cards, when we had the store on Nolensville Road, workmen got paid in cash envelopes every Friday at 2 p.m.,” says Friedman. “So my parents were always open till 9 p.m. on Friday and Saturday, because that’s when people could actually spend.”

No, Friedman’s didn’t start offering e-commerce when other stores did. But if you needed something shipped to you and knew the make and model number of the item, they’d drop it in the mail.

In the decades Friedman’s has been in business, it has served many neighborhoods, starting with a downtown store in 1949, and then outposts on Nolensville Road, Gallatin Pike in East Nashville and Bellevue. The Hillsboro Village location opened in 1972 and is the sole remaining storefront. Friedman isn’t particularly nostalgic or anti-progress. He’s grateful for the business that allowed generations to comfortably raise families while supporting the community. But he’s uncertain whether the next generation of entrepreneurs will be able to do the same.

When Friedman’s neighbor Jim Love, then the owner of Brown’s Diner, decided to retire in 2020, he looked for a buyer. Love owned both the property and the restaurant, which is housed in an old trolley car. At the time, the small restaurant had a leaking roof and needed many other repairs.

Real estate developers, of course, were interested in building on that intersection, which is prime residential density, close to bus lines, I-440 and Green Hills, and is within walking distance to a grocery store, Hillsboro Hardware (a legendary spot in its own right), and the Vanderbilt University campus and hospital. Love asked his son — Jimmy Love, founder and managing partner of Distribution Realty Group — to find a deal that would protect the future of Brown’s. He gave him a deadline of the end of year.

Hillsboro Hardware

Jimmy contacted many local chefs and restaurant owners, but couldn’t find the right fit. Then, on Dec. 28, 2020, when it looked like time was running out, he connected with Bret Tuck, founding partner and former chef of Edley’s Bar-B-Que. Tuck was ready for a new challenge, and despite having just 12 hours to sign on the dotted line, he bought the business. (The land is owned by an investor group.)

“Typically I would have said no to a deal in 12 hours,” says Tuck. “But it was [the height of the COVID pandemic], and I was ready for a little bit of a change. I love a project. I’m very interested in, ‘How can I figure out how to fix this or how can I make this better?’ Having to do it the hard way is a little bit more rewarding way to do things.”

Tuck, who is still an investor in Edley’s, was determined to preserve what people love about Brown’s — the burger, the staff, the historic photos on the walls — while making some upgrades, like fixing that leaking roof. Despite its downtrodden image (or maybe because of it), Brown’s has been a local institution since 1927. It reportedly holds the oldest beer license in the city, and folks like Gill — whose pickup-basketball friends head over after a game — rave about the burger.

As is the case at Friedman’s, Brown’s has staff members who have been loyal for decades. Ron Kimbro has worked behind the bar at Brown’s since 1986 and is determined to stay put until 2027, when the restaurant will hit its 100-year mark. Brown’s employees remember regulars’ orders and keep the peace — Kimbro says he knows of only two fights that have broken out in the decades he’s worked there. The Brown’s employees, with their relationships to longtime customers and their understanding of how the business worked and how the burger was seasoned, agreed to stay on after the sale. And that was part of what gave Tuck confidence that he could turn things around.

He also knew it “was going to be real tough.” One of his first days after buying the business, a crowd of regulars, including Gill, were eating burgers and talking. Someone asked, “Is that the new owner?” Tuck said yes. He started to introduce himself when someone shouted, “Don’t fuck it up!”

“They didn’t want it to change at all,” Tuck says. “But they knew it needed help. Everybody knew the roof was leaking on everyone’s head. My vision was to just keep the soul but make it competitive.”

He met with the neighborhood about a plan to add a deck, which added seating space and natural light without changing the dining room. He upgraded the kitchen to commercial equipment instead of warhorses like the old residential refrigerator. Yes, he fixed the roof and painted the bathrooms (more on that later). Then he set about looking at the menu.

Brown's Diner before renovations

In the background of a 1940s photo, Tuck saw an old sign referencing biscuits and learned that Brown’s used to be open for breakfast. “That first or second Sunday I was here, we had 20 Airbnb-ers come up Sunday morning for breakfast,” he says. “They thought, because of the name, that it was a diner.”

Now Brown’s is open in the mornings and serves an all-day breakfast menu, including hash browns as big as your head, with onions and other add-ons. The menu includes buttermilk biscuits, gravy, egg sandwiches, pancakes and coffee from Drew’s Brews.

Tuck upgraded the quality of the meat for the Brown’s burger, which is now served on buns from Charpier’s Bakery, but otherwise he left that classic alone. The full menu has some options for healthier eating, such as salads and wraps and a turkey burger — but wings, fried pickles and other standard diner dishes are there too. Tuck’s mom bakes cakes for the diner, and varieties change daily. Brown’s $3 hot dog could legitimately be called a “Recession Special.” This year, Brown’s launched a cocktail menu, with classics like the Tom Collins and the Old Fashioned, plus brunch cocktails to go along with the new breakfast menu.

But Brown’s is not just about being a diner with a reliable burger and a beer.

“Brown’s is known around the world for the hamburger, but it’s also a big songwriter hangout,” Kimbro says. “It was before I worked there, and hopefully when I’m gone. All the greatest songwriters in the world hung out there.”

Generally they do so on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, he says, because those are the nights people aren’t on the road. (Brown’s is open seven days a week.) Kimbro lists big-name customers — not just Prine and Gill, but Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, SteelDrivers founding member Richard Bailey, Don Everly and many more. (“Al Gore came in too, if you care about politicians.”) More than a decade ago, The Black Keys picked Brown’s as the locale for their first interview with the Scene.

“People come to town, [and] if they meet one famous songwriter, they are happy,” Kimbro says. “But where I was at Brown’s, I didn’t have to know them, they had to know me. I got to know them as people. Some of them were really great, and some of them you wouldn’t invite to your funeral.” (Kimbro also plays music, but is modest about his own contributions: “I strum a little bit, no threat to anyone who comes through.”)

The acts who played at Brown’s in the past were customers who just happened to play, stepping over cardboard boxes to make room for a guitar. “The music, we never advertised,” says Kimbro. “We used to call it ‘The Brown’s Rehearsal Hall.’”

Bret Tuck, owner of Brown’s Diner

Still, given the level of chops among the songwriters sitting at the bar, the lineups were impressive. As with the kitchen, Tuck decided to take the music lineup a little more seriously when he took over, clearing out the space to the side of the bar for a more definable stage and hiring someone to book acts, which are now publicized in advance. No one would call the now-cleared-out space for musicians a high-tech stage, but this is a gig many acclaimed songwriters want.

“The great thing about Nashville for me is a place like Brown’s that’s unassuming, slightly physically uncomfortable for the musicians, not fancy, not perfect sound, but requires the nuts-and-bolts immediacy of playing to a crowd and connecting,” says noted singer-songwriter Paul Burch. “I want to sing where John Prine and Don Everly drank a beer and had a burger.”

Most of the Brown’s upgrades seem to have passed the regulars’ test. The deck is busy most of the day, and it appears that, now that Tuck is a few years in, folks don’t seem to think he “fucked it up.” There’s one change, however, that Gill laments: painting over the graffiti on the men’s bathroom walls. There used to be a line, a response to the famous quote from actor Will Rogers: “I never met a man I didn’t like.”

“It said, ‘Will Rogers never met [name redacted],’” Gill laughs as he tells the story. He mentions the graffiti in “Brown’s Diner Bar,” his recorded-but-not-yet-released song about his favorite burger stop.

He’s talking about the graffiti when he sings: “The words on the walls of the men’s room are gold / Some were funny as hell, and some were just cold.”

Graffiti or no, Gill is right about one thing: “There ain’t many places like Brown’s anymore.”