Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy

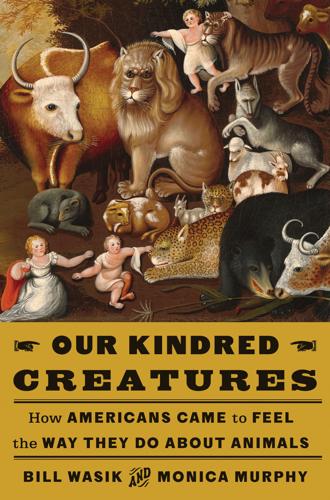

Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy’s Our Kindred Creatures: How Americans Came to Feel the Way They Do About Animals is a provocative, sometimes disturbing examination of Americans’ evolving attitudes toward animals from 1866 to 1896. It is also a study in empathy.

The book is divided into sections titled “Beachheads” and “Standoffs.” “Beachheads” covers the first 10 years of the period, tracing the birth of the animal rights movement and its early success in lobbying for anti-cruelty laws and creating systems of enforcement. “Standoffs” describes the movement’s shift in focus from prosecution to the engagement of the public’s compassion. These two approaches are embodied in the book’s central figures: Henry Bergh, a fire-breathing scion of a wealthy shipbuilding family who enlisted the clout of New York’s elite to found the ASPCA, and George Angell, a minister’s son whose goal was “nothing less than a moral revolution in America, one carried along by human emotion in rebellion against suffering of all forms.”

As the section titles suggest, Our Kindred Creatures frames the animal rights movement’s history as a series of battles. Its victories were often intertwined with the rapid social transformations of the time. George Angell built on abolitionists’ success as he advanced his belief “that resistance to war, racism, plutocracy, and animal cruelty were duties that walked hand in hand.” Many founders of local ASPCA chapters were women, who recognized and strengthened the movement’s moral connection to causes such as suffrage and temperance. And thanks to the growth of public education, the reformers were able to widely distribute anti-cruelty literature to children.

But the economic and social conditions of the Gilded Age also created the movement’s fiercest enemy: unchecked capitalism. Global trade networks funneled millions of dead exotic birds to milliners in major cities. The expansion of railroads and development of new technology such as refrigeration and the automated slaughtering machine enabled the meatpacking industry “to concentrate both wealth and suffering at an astonishing, unaccountable scale.”

The paradoxical effects of the Gilded Age on the animal rights movement are reiterated on smaller scales throughout Our Kindred Creatures. Extinction researchers bemoan the disappearance of a species while killing individuals of that species to study them. Henry Bergh rages against the number of dogs killed during Louis Pasteur’s development of a rabies vaccine, but he supports the killing of dogs by a scientist attempting to disprove the existence of rabies. At times, it seems that animal rights advocates were battling their own cognitive dissonance as much as they were fighting systemic greed.

Many reformers drew strength from the belief that “moral truths can be perceived intuitively by the human mind,” that they needed only to educate the public about animal cruelty to engage the “gut-level revulsion to suffering, instilled by God.” Wasik and Murphy also center empathy (minus the tinge of religiosity) in the structure of Our Kindred Creatures. Most chapters begin with an anecdote about a single species or individual — passenger pigeons, the urban horse, beluga whales, Jumbo the elephant — to evoke the reader’s compassion. Conversely, the authors cite a failure of imagination, empathy’s close cousin, as the reason the reformers “could not confront the slaughterhouses,” where tourists willingly came to witness the bloody spectacle of modern meat processing: “The reality of them simply could not be reconciled within their worldview.”

The reader might expect sections called “Beachheads” and “Standoffs” to lead to a third called “Victory” or “Defeat.” However, the authors cite the ongoing industrial-scale cruelty and suffering inflicted in slaughterhouses and on factory farms to argue that the fight for animal rights must continue today. Implicit and explicit parallels between the Gilded Age and the early 21st century abound in the book: the wealth gap, fears about immigration, controversy over the ever-shifting line between the government’s role and individual rights.

Wasik and Murphy point out that despite such divisive conditions, the 19th-century reformers succeeded in expanding Americans’ circle of care. They exhort their readers to make a similar “collective leap of imagination” to end the invisible suffering of our meat animals. Through both its structure and content, Our Kindred Creatures follows the blueprint of the early reformers in order to engage readers’ empathy and challenge them to “reckon with the moral obligations we have to all the creatures around us.”

For more local book coverage, please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.