Maestro: The dualities of Leonard Bernstein

Bernstein composed Broadway musicals, ballets and symphonies. He conducted Beethoven, Mahler and Stravinsky. A look at why a recent celebrated biopic couldn’t do him justice

One of 2023’s most audacious films was a queasy drama where a self-serious actor attempted to slip into the physicality of a real-life subject in an ill-judged body-snatch for a vanity biopic. No, not Maestro. Yes, May December, which may have, in fact, been too audacious for those in its reticle. Todd Haynes has never met an expectation he didn’t subvert, whether he is reworking suburban melodramas, chasing elusive personas, or doing both, as in the case of his latest. With May December, he side-eyes a predatory industry cobbling together real-life stories as vapid spectacles, while challenging an audience all too content to consume. It was telling that May December got little love from the industry and Maestro got plenty. The former earned one Oscar nomination to the latter’s seven (which included the coveted Best Picture).

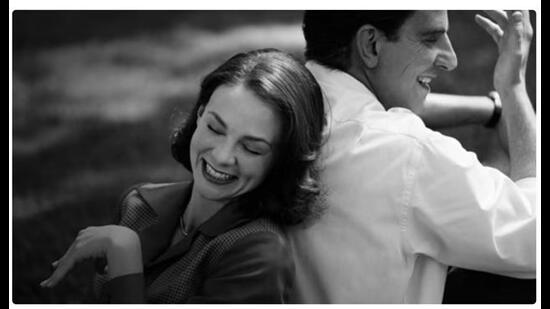

Neither took home a trophy. But the discrepancy in industry and public recognition makes plain why show-offy biopics remain Oscarbait. Maestro felt more like a big-screen slow clap for Bradley Cooper’s multitasking (as actor, writer, director and producer) than Leonard Bernstein’s music. When the subject is an American music icon, one would think the centrepiece would be the music. Cooper clearly thinks otherwise. As he erected an awkwardly miscalculated shrine in Bernstein’s memory, he presents a compressed snapshot of an atypical marriage instead of an overarching portrait of a towering artist. But the awkward miscalculation came not from the greater focus on Bernstein’s relationship with his wife Felicia Montealegre (played by an excellent Carey Mulligan), but the startling lack of interest in his music, from the process of its creation to its power to its place in 20th century culture.

Bernstein composed Broadway musicals, ballets and symphonies. He conducted Beethoven, Mahler and Stravinsky. “Life without music is unthinkable. Music without life is academic. That is why my contact with music is a total embrace,” he said. Cooper’s contact with Bernstein’s music is at best a facile half embrace, at worst a pedantic performance. When Bernstein conducted, he appeared to embody the music and the tides of emotions the composers themselves experienced while composing. When Cooper conducts as Lenny, the mimicry strives for such a cold precision, the sincerity proves stifling. All the wild thrusting of the arms, all the rocking and soaring and gesturing, all the sweat beading the brow, all the six years supposedly spent learning to conduct, come off as an ego trip, so it can be sold by PR as a feat of artistic engineering worthy of the maestro himself.

The famous Hungarian violinist Carl Flesch once remarked that conducting is “the only musical activity in which a dash of charlatanism is not only harmless, but positively necessary.” Taking the remark as a guideline, Cooper goes all out to conduct Maestro like a symphony orchestra. With one hand, he sets and varies the tempo of his performance and by extension the film. With the other, he cues harmonies and counterpoints, diminuendos and crescendos. He imposes his will on the orchestra, but he can’t inspire all his collaborators (save for Mulligan) to find the passion of the piece to transcend all boundaries. On The Art of Conducting, Bernstein said, “The conductor must not only make his orchestra play, he must make them want to play. He must exalt them, lift them, start their adrenalin pouring, either through cajoling or demanding or raging. But however, he does it, he must make the orchestra love the music as he loves it.” As educator, mentor and TV personality, Bernstein spread his infectious enthusiasm for classical music to everyone who was watching and listening. In failing to capture this quality, Maestro leaves those unfamiliar with him or his music locked outside. Cooper made the baffling choice of having partners, interviewers and biographers list out his musical talents, rather than show them. The end result has the earmarks of a rough draft of a much better film it could have been. If only Cooper the actor could have bailed out Cooper the director, or vice versa.

“Duality is of Bernstein’s essence: He was Whitmanesque in his ability to contain contradictions and triumphantly survive,” wrote biographer Humphrey Burton. Maestro spells out an unremitting tug-of-war between Bernstein the conductor and Bernstein the composer, pitting the former’s penchant for extroversion against the latter’s precondition for introspection. Becoming a celebrity conductor brought unwanted public scrutiny of his troubled private life, his queerness, and his politics. For decades, Bernstein was spied on by the FBI for his support of civil rights, anti-war movements and other progressive causes. In 1965, he marched with Martin Luther King Jr from Selma to Montgomery, and joined the Stars for Freedom Rally. In 1970, he and his wife hosted a fund raiser soirée for the Black Panther Party, immortalised by the gatecrashing Tom Wolfe in the article Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s. In 1948, he performed for Israeli troops upon the creation of the state of Israel. In 1979, the same man signed a petition opposing the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. The social timing and political engagement are imperative to understand Bernstein’s work. Jonathan Cott wrote in Dinner with Lenny (2013), “Unlike almost any other classical performer of recent times, Leonard Bernstein adamantly, and sometimes controversially, refused to compartmentalize and separate his emotional, intellectual, political, erotic and spiritual longings from the musical experience.” But Cooper prunes away this most interesting side of Bernstein’s life, like many biographers of the past. With huge chunks of the 1950s and almost all of the 1960s omitted, his reductionist treatment is far less fascinating than the actual historical record.

With such a glaring omission, we don’t get a sense of how it must have been for Bernstein to live through one of the most turbulent times in American history as an artist, a married gay man, and a person of interest for the FBI. Decades are accordioned into a couple of hours about a committed but complicated marriage. Montealegre wasn’t oblivious to her husband’s closeted homosexuality. Not long after their marriage had run into its first signs of trouble, Montealegre wrote to Bernstein in a letter, “I am willing to accept you as you are, without being a martyr or sacrificing myself on the LB altar. (I happen to love you very much — this may be a disease and if it is what better cure?) It may be difficult but no more so than the “status quo” which exists now... let’s try and see what happens if you are free to do as you like, but without guilt and confession.” This was easier said than done. As shown in the film, the more openly Bernstein carried out his affairs over the years, the more Montealegre realised she had ignored her own needs in allowing him to satisfy his. She was a rising star on the Broadway stage before she slid into the role of the put-upon wife of a genius, deferring her dreams to raise their children. During a word-for-word recreation of a 1955 interview with the couple, Lenny answers questions about his primary occupation and the composer-conductor duality. As the camera zooms in on him, it pushes Felicia to the edge of the frame. Years of marital tension boils over in a heated argument captured in a single medium shot. Felicia chides Lenny for his increasing sloppiness with his affairs and for using his gift as an excuse for selfishness. The hurt in her voice and her eyes reveal a woman craving for personhood that had been sacrificed at the altar of their arrangement.

Leading a double life left Bernstein plagued with guilt over the rift it created in his marriage. Burton, in his biography, recounts how a young Bernstein described the guilt as “a canker in my soul” to a girlfriend. As Montealegre’s parenthetical statement reveals, queerness was still being treated as a disease to be cured. It was a time when women, knowingly or unknowingly, served as a beard to gay men. Paul R Laird’s biography recounts how the Russian conductor Serge Koussevitzky had advised Bernstein to marry Montealegre to keep the spotlight off his private life. The scene plays out in the film through charged suggestions. Koussevitzky (Yasen Peyankov) tells his protege he could be “the first great American conductor,” as long as he keeps his life and work “clean.” Bernstein is further encouraged to change his last name to Burns because the gatekeepers of the American orchestras may hesitate in hiring a conductor with a Jewish name. Bernstein refused of course.

As to the film’s examination of Bernstein’s relationships outside of his marriage, Cooper sifts from available record in a manner that minimises their importance. Serious relationships are cast as fleeting affairs, like a homosexual hiccup in a heterosexual marriage. One of Bernstein’s formative lovers was clarinetist David Oppenheim (played by Matt Bomer), a man with whom he even shared the same therapist to “cure” them of their homosexuality. In fact, it was Bernstein who urged Oppenheim to marry actress Judy Holliday as a beard. In one scene, he runs into Oppenheim and his second wife Ellen Adler (Kate Eastman) on a stroll in Central Park and reveals jokingly to their baby that he has slept with both of her parents. Later in the 1970s, Bernstein met classical radio station director Tom Cothran (Gideon Glick), the man for whom he would go on to leave Montealegre few years later. The separation was brief as Bernstein moved back in to the family home to take care of the cancer-stricken Montealegre until her death. Maestro shows us a man heartbroken by grief, but doesn’t show us the emotional impact of losing Cothran a decade later to AIDS, as if the gay relationships were mere interludes between the greatest hits and missteps of the marriage.

Maestro introduces us to Bernstein leaping from bed as a fully formed musical genius who became an overnight star at 25, when he made his New York Philharmonic debut, stepping in for a sick Bruno Walter at short notice and without a single rehearsal. The journey from growing up outside of Boston to studying at Harvard to the Carnegie Hall podium is of little to no interest to Cooper. Nor are the influences he picked up along the way. Aaron Copland (Brian Klugman), who was Bernstein’s “only real composition teacher”, is cast as a walk on part. Letters, cited in Burton’s biography, reveal the two were even lovers for a while. But Copland, like Koussevitzky, cautioned Bernstein about letting personal affairs get in the way of professional ambitions. “I keep being properly impressed by all the offers, interests, contacts, personalities that flit through your life. But don’t forget our party line — you’re heading for conducting in a big way — and everybody and everything that doesn’t lead there is an excrescence on the body politic.” Despite their concerns, Bernstein wasn’t entirely sure of how his mentors perceived him. “I don’t know whether they think of me as a conductor or a composer, you know. Maybe they want me to be a conductor so that I can play their music and they don’t want me to be a composer so that I’m not kind of competition for them,” he wrote in a letter (from a collection edited by Nigel Simeone).

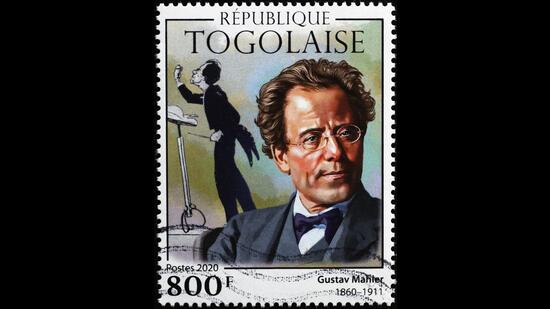

Of all the composers, Bernstein felt a special connection to the work of Mahler. Maybe because the Austrian composer too suffered the same kind of schizophrenia: torn between conducting and composing. As composers, both looked to reimagine the symphony as a form. Eulogising Mahler in one of the Young People’s Concerts, Bernstein said, “No composer goes quite so far in each direction, so happy and so sad. When Mahler is sad, it is a complete sadness; nothing can comfort him, like a weeping child. And when he’s happy, he’s happy the way a child is – all the way… Here was this grown-up, very sophisticated, learned man — with children of his own — and a heart full of struggles between the different voices fighting inside him, always trying to feel pure and innocent again like a child. And that too is one of the battles that he had: the battle of the double man, half man, half child.” Bernstein could very well be describing himself here. When Cooper as Lenny conducts Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony in the iconic performance at Ely Cathedral, he tries to capture how the composer and conductor became one with the work. The only problem is the scene plays like a testament to Cooper’s mimicry, not Bernstein’s mastery. Cooper may worship at the altar of Bernstein, but the art, the duality and the contradictions of the real Lenny are well beyond him.

Prahlad Srihari is a film and pop culture writer. He lives in Bangalore.

Catch every big hit, every wicket with Crick-it, a one stop destination for Live Scores, Match Stats, Quizzes, Polls & much moreExplore now!

See more