K Vaishali – “Many literature festivals ignored me”

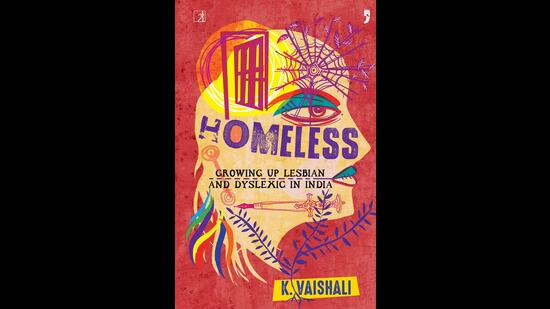

The author of Homeless; Growing Up Lesbian and Dyslexic in India on winning the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar 2024 for her memoir

Congratulations on winning the award. How do you look back on your journey? How has this honour altered the way you view yourself, and how people approach and interact with you?

Thank you! I am so thrilled to be the first openly lesbian and openly dyslexic person to win the Yuva Puraskar. When Homeless was published in March 2023, I was so excited to see the buzz it received in the initial few months. The book received numerous positive reviews, including from many reviewers in the queer community, which was incredibly satisfying.

The months following my book’s release were disappointing. Despite my publisher’s efforts and my own financial investment, the book remained confined to the queer and disabled filter bubble. Even within the queer community, outreach to media platforms, influencers, and activists yielded few responses.

I had little success with mainstream book awards, and despite offering to fund my own travel and stay, I was only invited to speak at the Rainbow Lit Fest in Delhi and the Hyderabad Literary Festival. Many other lit fests ignored messages from me and my publishers. As a debut author, promoting the book felt lonelier than writing it.

Winning the Yuva Puraskar gives me hope that my book could spark dialogue and reach mainstream readers to facilitate difficult conversations and shift societal attitudes. Though it’s about my experiences as a queer disabled individual, it delves into universal themes of loneliness, acceptance, and finding one’s place in the world that any adult can relate to.

Winning the Yuva Puraskar boosts my confidence. As a writer with a reading and writing disorder, I’ve struggled to see myself as a talented writer. Perhaps now I can also promote the compelling writing in my book along with its content. Writing with my learning disorders has been challenging, leading me to question if I should write another book. Now this award has reignited my passion for writing.

When you began to write a book about your experiences with homophobia and ableism, were you sure that you wanted it to be a memoir or did you toy with the idea of an autobiographical novel?

When I began writing this book, I intended it to be a fictional work. Perhaps subconsciously, I was fearing the serious consequences of revealing my lesbian and dyslexic identity. Yet, unintentionally, I infused much of myself into the protagonist, drawing from my own experiences to shape their back story and motivations. Reflecting on it now, I realise I was driven to write a memoir and share my story, using the guise of fiction to shield myself from potential repercussions.

As life progressed, I willed myself to a safe space at home and work — and suddenly using lesbian and dyslexic labels didn’t seem like such a big risk to my survival. I was rereading my drafts and wondering if I should keep it as a fiction book or rewrite it into a memoir. I attended a nonfiction writing workshop organised by Yoda Press to understand the different structures and creative devices I could use to tell my story. The workshop helped me so much; I reached out to Yoda Press’s founder Arpita Das to mentor me and she encouraged me to write it into a memoir as she read my draft and strongly felt it’d make a powerful and compelling one. She was very kind to pitch the book to Simon & Schuster India to publish under their joint imprint with Yoda Press. She came on as my editor and helped me hone my voice and tell my story effectively.

Unlike a traditional memoir, mine has a “present” rooted in a moment from my past, infusing the book with a restless anxiousness that highlighted the threats of unsafe spaces. I’ve used narrative digressions to weave the past into this “present”, providing context while keeping readers engaged. I aimed for each chapter to encompass all aspects of my life simultaneously, avoiding separate “lesbian” and “dyslexia” sections. However, organising the manuscript required breaking it into passages, colour-coding them, and meticulously rearranging them to craft a cohesive narrative — a process that consumed me for days and many sleepless nights.

Arpita was my dream editor for many reasons, but mainly because she didn’t advise me to rewrite my memoir into a traditional voice or structure. She saw the reasons behind my choices, sometimes more clearly than I did, and encouraged me to experiment. She’d also ask many questions through the manuscript, at times a simple “why?”, which would make me recall many memories and provide important contexts that made the book richer. She also gave me a very important input early on — start the book at the most crucial place where your story begins even if it isn’t the chronological start of the story. That’s how the book begins with me coming out to my mother, which is the most crucial turning point of my story.

You write about feeling lonely in queer circles in Mumbai and Ahmedabad because they were dominated by gay men and their discussions about sexual encounters. Does this dominance come from having a higher number of gay men in these spaces, or the denial of opportunities to lesbian women, trans people, intersex and asexual folks who are present?

In the late 2010s, I wasn’t on social media or dating apps and found queer circles by meeting a queer person in real life, usually at a protest or a pride march. Most gay men I asked found these circles through Grindr, explaining why these spaces were dominated by gay men discussing sexual encounters.

Other identities within the LGBTQ+ community lack a singular space they frequent like many gay men frequent Grindr. This helps gay men form communities easily, as they frequently connect and add each other to these circles. Since these spaces have a cisgender gay men majority, cisgender women and trans folks often stop attending when they don’t find others like themselves.

Things are much different now. In Hyderabad, the Queer Women Collective (QWC) organises events for queer women, providing a safe space to socialise and perform. I perform stand-up at some of their events. I’m also part of a queer women’s sports group where we play badminton or cricket regularly. The queer women community in Hyderabad is thriving and has become one of the city’s larger queer circles.

You also write about your frustration with dating apps. I was drawn to your insight that attraction need not be instantaneous; it can happen over subsequent meetings. The app-driven dating game pushes people to meet only those candidates whom they find attractive. How does this impact the way people curate and present themselves?

I used dating apps on and off for a few months, finding the experience frustrating. The focus on pictures made it a game of attraction, pressuring me to hide parts of myself, like my neurodivergence, and initially choosing photos that didn’t show my full body due to internalised fat phobia. This struggle between being authentic and seeking romantic attention often led me to quit the apps.

I also struggled to find the right person I wanted to talk to. Attraction wasn’t instantaneous for me. I was drawn to women with whom I could form an emotional bond and trust, which was hard to gauge from pictures and prompts. This is not just a queer issue — many of my heterosexual friends also find dating apps ineffective, often investing time in people they eventually realise aren’t right for them.

When I interviewed stand-up comedian and disability rights activist Nidhi Goyal in 2020, she told me, “Right now, there is homophobia in the disability rights movement, casteism in the queer rights movement, ableism in the Dalit rights movement, and so on. We will have to address the structural inequalities in our own movements; that is a precondition for building progressive alliances.” What are your thoughts on this, based on your own journey of growing up lesbian and dyslexic? Also, how has your book been received by individuals, collectives and movements around those identities?

Yes, I agree with Nidhi.

I felt a deep sense of belonging at a book club event in Hyderabad with mostly neurodiverse women discussing my book. We uncovered many insights about the neuroqueer experience, and it felt like everyone was speaking my language. This made me realise how often I conceal parts of myself in other queer or disabled community spaces.

I’ve noticed that when queer readers review my book, they mostly focus on the queer aspects, rarely mentioning other topics. It makes sense they relate most to those parts, seeing themselves reflected. I hope my book, intersecting queer and disabled identities, fosters new allies in both communities.

Intersectional identities are getting more attention lately. After Homeless, Abhishek Anicca’s book The Grammar of my Body also talked about ableism and the queer-disabled experience. We also have more collectives like the Revival Disability India, The Queer Muslim Project, Dalit Queer Project, etc. that are raising awareness about intersectional queerness.

While documenting your life in a university hostel in Hyderabad, you have commented on your Brahminical upbringing. Was that brought to your notice, or did it come from within? How does that awareness shape your own participation in the queer movement in India, which is splintered because of the variety of issues that people wish to prioritize?

I went through my school years without having any exposure or awareness about caste issues. I think that’s by design. The private schools that I attended were only affordable to middle-class people with generational socio-economic privileges, which systematically excluded those who weren’t part of the general caste.

I joined the University of Hyderabad a few months after the “institutional murder” of Rohith Vemula. The atmosphere in the university was charged with protests and everyone was talking about caste and what happened to Rohith. Listening to others in the university was eye opening and it made me reflect on the role my caste has played in my life and the privileges I have from it.

I am still educating myself on caste realities. My partner belongs to the Other Backward Class (OBC) community and her struggles and life experiences help me understand caste issues better. I believe we have to take a step forward together and the queer community needs to keep fighting till there is no discrimination based on sexuality and gender, but also caste, disability status, or religion.

What were the many meanings of “home” that you were referring to in the title? Do you think that your readers got what you intended? The book ends with you buying a three-bedroom house with your partner but we get barely any details. Are you writing another book about what it meant to build a home after exiting the one you grew up in?

The word “homeless” packs a lot of meaning for me. I’m still discovering what it fully means to me. Of course, there is the absence of a literal home; the struggle to put a roof over my head. There’s also the homelessness of never having had a stable roof over my head all my life. My family kept moving from city to city and I grew up in 12-13 homes through my childhood. There’s no one house where I could say, “This is the place where I reminisce the most. This is the house I have the most memories in.” There is no notion of a childhood home.

Home represents comfort and security. Yet, I never felt this in my parents’ house. There, I couldn’t be myself; every aspect of my existence felt like a performance for them. Enduring nightly abuse from my alcoholic father, it was far from a home. School offered no respite either. Undiagnosed dyslexia and dysgraphia made each day a struggle.

Belonging can also be found in relationships, but constant displacement left me without stable friendships. Unable to confide in classmates about my home life or relate to their experiences, I felt isolated.

Bullying for my weight led me to hide my body, wishing to exist only as a soul. Even my body didn’t feel like home.

I had also never seen a home for someone like me. I had never known of two women sharing a house alone without a man present — a future like that didn’t seem possible for me.

I haven’t read an interesting take on the title of the book yet. Some readers have misunderstood it and have asked why it’s called “homeless”. They see my homelessness as a brief struggle to find housing. But when I was thinking of a memoir, I had this overwhelming feeling that only the word “homeless” encapsulated how I felt at the time. I couldn’t find a better title, so I went with it.

And yes, I want to write another memoir about the idea of home, but I also have other ideas for my next book.

What lessons did you learn while navigating the Indian publishing industry with your debut book? What advice would you offer other debutant(e) authors?

As a debut author, gaining attention for my book has been challenging despite having a good publisher. With so many books published each year, writers must actively promote their work. Success often depends on being marketing savvy, which is why some books stay in the spotlight through effective self-promotion and networking.

When I published my book, I wasn’t on social media and struggled to use it effectively. My efforts to understand algorithms and create engaging content didn’t work well because I’m not skilled in that area. With a full-time job, I could not dedicate all my time to promoting my book, so I worked with Keemiya Creatives — a book marketing agency — to develop a strategy and create content for me. This kept my book visible on social media.

My advice to debut authors is to understand your book’s strengths and uniqueness. Know why readers should read your book. If you are not good at social media, seek help from someone who is, preferably before your book is published. Many marketing agencies can help you reach your target audience, though it can be expensive. If you can’t afford hiring an agency, there are many tutorials online that can help.

Please tell us more about your full-time job and the work you’ve been doing towards diversity, equity and inclusion.

I work as a technical Writer & Leader—LGBTQ+ Business Resource Group for Japan and the Asia-Pacific region at a tech company. I also host a podcast called the Queerious Connections, which is about queer identities, intersectional views, and the challenges of being a person in the world. In December 2023, I was the delegate for Learning Disabilities at the International Purple Fest — a festival that celebrates people with disabilities and is organised by the Government of Goa and the Government of India.

Chintan Girish Modi is a freelance writer, journalist and book reviewer.

Catch every big hit, every wicket with Crick-it, a one stop destination for Live Scores, Match Stats, Quizzes, Polls & much moreExplore now!

See more