Background

Year after year, Springfield makes headlines for bribery, corruption and even bullying. A report from the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Department of Political Science found Illinois to be the third most corrupt state. And a BGA Policy analysis found, ethical oversight of Illinois’ legislature is uniquely weak among the 50 states.

In Illinois, the two entities that oversee the legislature are the Legislative Ethics Commission and the Legislative Inspector General. The Legislative Ethics Commission acts as a “quasi-judicial body,” while the Legislative Inspector General performs the actual investigations into alleged wrongdoing.

The Legislative Ethics Commission is almost entirely comprised of active lawmakers, the very people the commission should be holding accountable. The commission also governs the investigations of the Legislative Inspector General. The Legislative Inspector General investigates “fraud, waste, abuse, mismanagement, [or] misconduct” of members of the legislature, or employees of the legislative branch, but the LIG is hamstrung from being able to conduct effective investigations by the office’s inability to issue subpoenas or independently release reports after finding wrongdoing.

Legislative Ethics Commission

The commission is made up of eight members appointed by the four party leaders in the House and Senate: the Speaker of the House, Senate President, and minority leader in each chamber. Each of the four leaders appoints two members to the commission. Illinois is unique in allowing members of the legislature to appoint all members of the legislature’s oversight body.

Illinois statute says commissioners must “have experience holding governmental office or employment,” but cannot be “a State officer or employee other than a member of the General Assembly,” leaving few eligible except for legislators, the exact people the LEC should be holding accountable.

For this reason, the commission is often composed mostly, if not entirely, of members of the general assembly. As of January 18, 2023 six of the eight commissioners are members of the general assembly, and the other two commissioners were members of previous general assemblies (this may change as the new general assembly begins).

There are four states, including Illinois, that have an ethics commission specifically for the legislature. Illinois is the only one of the four where all members are appointed by the legislature.

Illinois also is unique when expanding the analysis to all ethics commissions that have some jurisdiction over the legislative branch. The National Conference of State Legislatures found 41 states have at least one ethics commission that oversees the legislature (this excludes Iowa’s commission that only oversees those running for legislative office), with three states (Alaska, Washington, and New York) that have two commissions.

Using this analysis, BGA Policy found that of the 44 commissions:

- 33 have an odd number of members (preventing deadlocked votes)

- 41 have at least one member appointed by a non-legislative body

- 28 have a majority of members appointed by a non-legislative body

Illinois, by contrast, has a single body made up of an even number of members, all appointed by the legislature.

Because of this, Illinois’ commission is more easily subject to gridlock, as well as ineffectual oversight, than the commissions in other states. This situation is compounded by having a weak Legislative Inspector General. The commission, being made up of the very people they should be holding accountable, has little incentive to allow the Legislative Inspector General full rein to investigate wrongdoing, and instead is able to keep the legislative watchdog on a short leash.

Legislative Inspector General

The LIG’s position has become more important than ever, with allegations or criminal conduct by members of the legislature having increased in recent years. The chart below shows the number of allegations (not including those referred to other bodies) from 2018 to 2021.

As laid out in the Association of Inspectors General’s Statement of Principles for Offices of Inspector General, “The OIG should be placed in the governmental structure to maximize independence from operations, programs, policies, and procedures over which the OIG has authority.”

The office of the Illinois Legislative Inspector General, as currently constituted, falls far short of these standards. Instead of independence, the Legislative Inspector General needs permission from the Legislative Ethics Commission in order to:

- Release their own reports;

- Subpoena people for investigations

- Request documents or materials related to their investigations.

For these reasons the former LIG Carol Pope called the role a “paper tiger.” And former LIG Julie Porter noted that the fact that the commissioners of the LEC all are appointed by leaders of the legislature creates a circumstance in which “the fox is guarding the henhouse.”

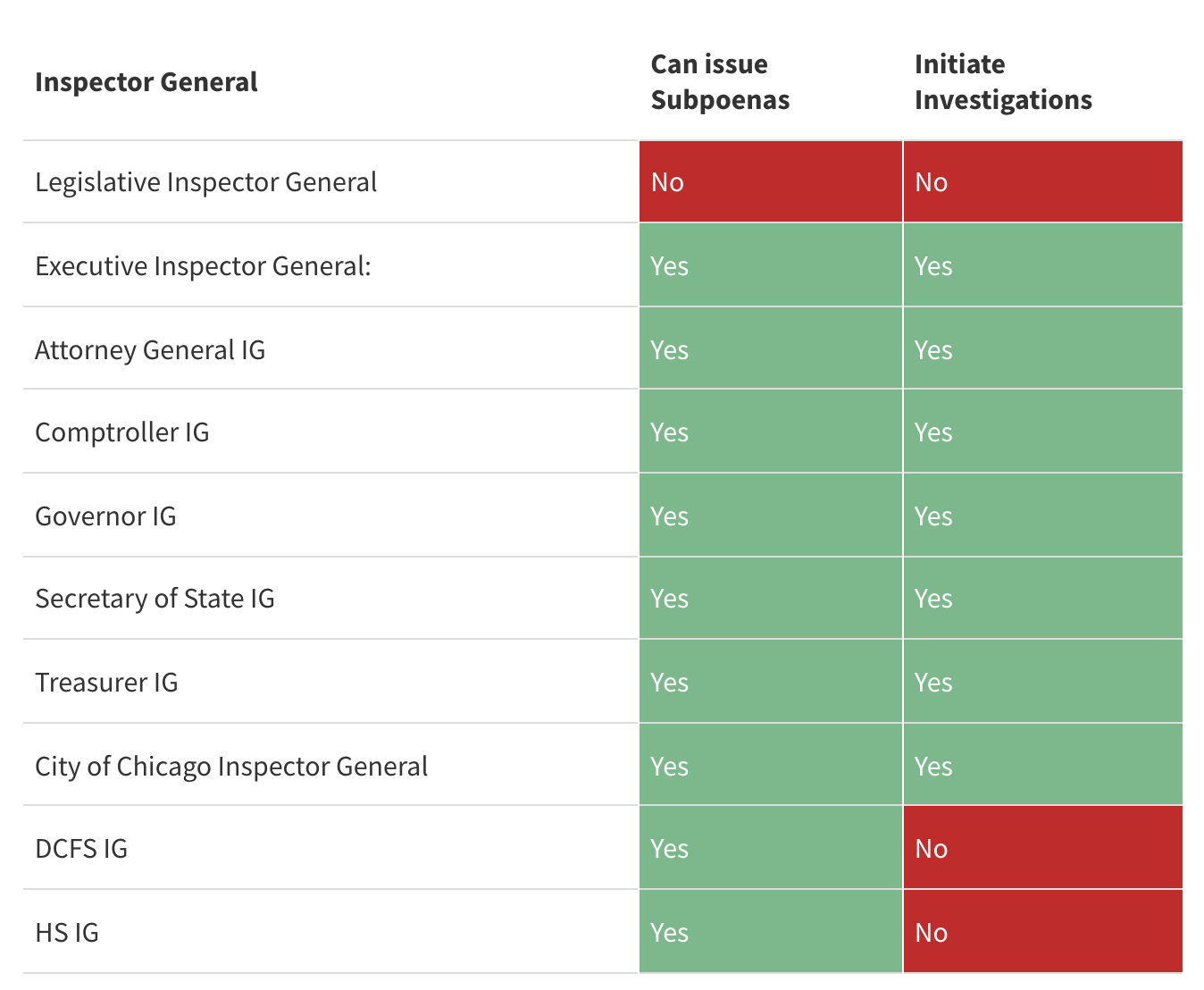

Limitations placed on the Legislative Inspector General also make the LIG uniquely weak when compared to other Inspectors General in Illinois.

Since the Legislative Ethics Commission oversees the Legislative Inspector General, and the Legislative Inspector General has no prosecutorial powers of its own, even if the LIG finds a reason to file a credible report, the LEC can block the report before it reaches the public.

Since November of 2017 the LIG has requested seven reports to be published, but only five ever saw the light of day. The LEC “did not agree to publish” two of the reports. No disclosure or explanation of the Ethics Commission’s decision was required, leaving the public uninformed, thereby potentially undermining confidence in both oversight bodies.

One of those reports was in 2019. Former LIG Porter wrote in the Chicago Tribune that she issued a founded summary report that found “a legislator engaged in wrongdoing,” but the Legislative Ethics Commission refused to publish it.

Past LIGs have called for the independence to release their own reports. Former LIGs Porter and Pope both have called for allowing the LIG to issue their own reports. In the words of Illinois’ first LIG, Thomas Homer, “reports finding legislator misconduct are unlikely to ever see the light of day. This is not fair to other legislative employees, nor is it in the public interest. I am unaware of any other inspector general who is required to operate under such secretive guidelines.”

Conclusion

This is not the first time the BGA has pointed out that the Legislative Inspector General is a weak oversight body, further hampered by the very nature of the Legislative Ethics Commission. In 2020 BGA pointed out that the dynamic between the commission and inspector general is dysfunctional. This dysfunction benefits only the lawmakers who commit wrongdoing, and harms the public.

There has been some progress since 2020. Although the Legislative Inspector General cannot launch an investigation on their own, if there is a complaint sent to the Legislative Inspector General’s office they no longer require approval from the Legislative Ethics Commission to investigate that complaint. The Legislative Inspector General still lacks the subpoena power shared by its peers, and lacks the ability to publish their own reports allowing the commission to muzzle our state’s legislative watchdog.

As this BGA Policy analysis shows, Illinois stands as an aberration in this respect. As the BGA said two years ago, our ethics commission “has a fox-guards-henhouse organizational structure and a built-in partisan deadlock. The upshot is that if the LIG wants to investigate potential wrongdoing by a lawmaker, a group of fellow lawmakers — proxies for caucus leaders — can kill it at the front end or bury the findings at the back end.”