Gay bars. Ask any member of the LGBTQIA community to tell you a story about one and they’ll regale you with memories. Good ones, bad ones, wild ones, emotional ones—because for decades, these spaces have been homes to a community. They ushered us into adulthood; they provided sanctuary to be ourselves. We mourn them like family members after they’re gone.

But “everything closes,” as formerly local author June Thomas summed up at her book talk earlier this month. So if everything is ephemeral, what makes gay bars so special?

The stories of these spaces are interwoven with our individual and collective histories. And in D.C. that history runs deep. According to the Rainbow History Project’s archives, more than 200 gays bars have set up shop in the District since the 1920s—decades before June 28, 1969, when the Stonewall Riots marked an essential turning point in the gay rights movement.

“The reason Pride exists,” says Ed Bailey, a well-known local DJ and gay nightlife entrepreneur, is “because there was a bar where a thing happened. It’s not like it’s surprising it happened at a bar. Of course it happened at a bar. Because that’s where everyone was, right?”

For the 55th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, City Paper sought to document a portion of our city’s shuttered gay bars and collect memories of those spaces from the people shaped by them, and who, in turn, have shaped D.C.

Like all histories, these are complicated. Racism, sexism, and transphobia permeated many gay spaces, making these spots unsafe for certain members of the LGBTQIA community. Carding, in which bars targeted people of color by requiring them to show multiple forms of ID, was all too common at predominantly White spaces. Other bars barred entry to trans people.

“It was an awakening for me … I thought as a discriminated against population, we would all be together,” says 68-year-old artist, activist, and native Washingtonian Christopher Prince, about the racism he experienced as a Black man at White gay bars in the 1970s and ’80s. Those experiences, he says, made him realize that “these White gay guys aren’t any better than the White straight guys.”

Landlords in wealthy neighborhoods often refused to rent to gay bars, sending those spaces into out-of-the-way neighborhoods often deemed “unsafe.” In a way though, as Thomas noted, these more desolate areas provided bar-goers cover from being recognized and outed at a time when violent homophobia was more prevalent. That said, violence wasn’t uncommon at gay bars, where robberies and fights between patrons sometimes occurred.

But queer bars—especially following the gay and Civil Rights Movements—weren’t just bars. They doubled as meeting spaces and activist hubs. They played host for political events and fundraisers, and helped raise money to fight AIDS and fund gender-affirming care. As Little Gay Pub’s co-owner Dito Sevilla sums up, “Twenty-five years ago, we didn’t have community centers or churches. That wasn’t where you met gay people. You met them in bars.”

City Paper’s incomplete history begins in the 1950s, with bars that blacked out their windows to protect patrons from spying eyes. It covers the rise and fall of gayborhoods, and ends in a city that, while more out and proud than ever, has some asking: Where did all the gay bars go?

Queer bars are still here, but they’re different. They’re less separatist—you’re likely to find a mix of all identities at today’s watering holes. Nightclubs with 70-foot ceilings have largely vanished. And the bars themselves are more sanitized—you probably won’t find porn playing in bathrooms in 2024’s gay bars.

Below we attempt to convey what some of our past bars were like through a collection of stories from the generations of queer, trans, and gay folks who’ve called the D.C. area home. Our spaces may be temporary, but our words are forever.

Through the Decades

1950s

Nob Hill Restaurant, 1101 Kenyon St. NW. 1957–2004

Before it became beloved dive bar Wonderland Ballroom, the two-story Columbia Heights establishment was home to one of the oldest and longest operating Black gay bars in the country.

Nob Hill began as a private social club for Black gay men in 1953, and opened its doors to the public in 1957. At a time when racism and segregation ruled queer nightlife, the no-frills bar became a vital gathering spot for the city’s Black gay population. By the ’70s, new bars such as Bachelor’s Mill, the Clubhouse, and La Zambra gave Black gays more options. Nob Hill also found itself competing with White bars that began, sparingly, to admit Black patrons in the ’70s and ’80s.

Still, Nob Hill remained important to the community through to its closure in 2004. It was not only a site for leisure and entertainment, but for organizing and activism. According to the Rainbow History Project, Nob Hill hosted the city’s first AIDS forum for the Black community.

Christopher Prince, 68, remembers the bar’s crowd being socioeconomically mixed. Its proximity to Howard University brought students, “but it was very much a neighborhood place,” he says. “So you had that cross section.”

Prince recalls dim lighting, greasy food, soul music, multiple dance floors, and male strippers, though he spent most of his time there talking with older guys. The bar developed a reputation for having an older crowd, earning the nickname “the Wrinkle Room.”

“It was so cruel, but the kids used to call it ‘wrinkles.’ ‘Oh, we’re gonna go up to wrinkles.’ Because it was nothing but older men,” says Prince.

By the time Nob Hill shut down, following a number of city code violations, it was the oldest continuously operating LGBTQIA nightlife establishment in the District. It was also, in Prince’s memory, a place that was increasingly targeted for robberies and harassment. “We should’ve really fought to keep that place open,” says Prince. “We weren’t able to protect our own .… There’s something a little tragic about that.”

1960s

The Black Nugget, 2504 14th St. NW. *1964-1968

“My favorite gay bar going back … 35-40 years … was the Black Nugget. You don’t hear about that one much,” says D.C. native, former sex worker, and longtime trans rights advocate Earline Budd. Now in her mid-60s, Budd currently works at HIPS, but her activism dates back to the 1990s when she began educating the LGBTQIA community about HIV/AIDS.

Before she was an activist, though, she was a young teen who frequented the bar at 14th and Chapin streets NW, where she says many of the city’s transgender residents were regulars. A few years ago, Budd described the Black Nugget to the Rainbow History Project as a hangout for trans street kids. Though the bar saw its share of violence (“every weekend when we went there somebody automatically got stabbed or cut,” Budd recalls), she says, “It was the place to be.”

A popular cruising spot, Budd remembers the long bar running down one side of the narrow room where patrons, often trans women, would perch. “That was the thing,” she says. “You want to sit at the bar because you want to get cruised .… When I started going and [men] were giving, ‘Damn you is fine. Would you like to dance?’ And I said, ‘Me?’ And then we would get up and slow drag .… That’s what it was about.”

But it was more than dancing. Inside, Budd built a community. “I was received by the individuals that went there as just being a young person coming out .… They kind of helped me to move along that transition of being—not transgender back then, because we didn’t use transgender, we used gay. And they helped me. They took me in.”

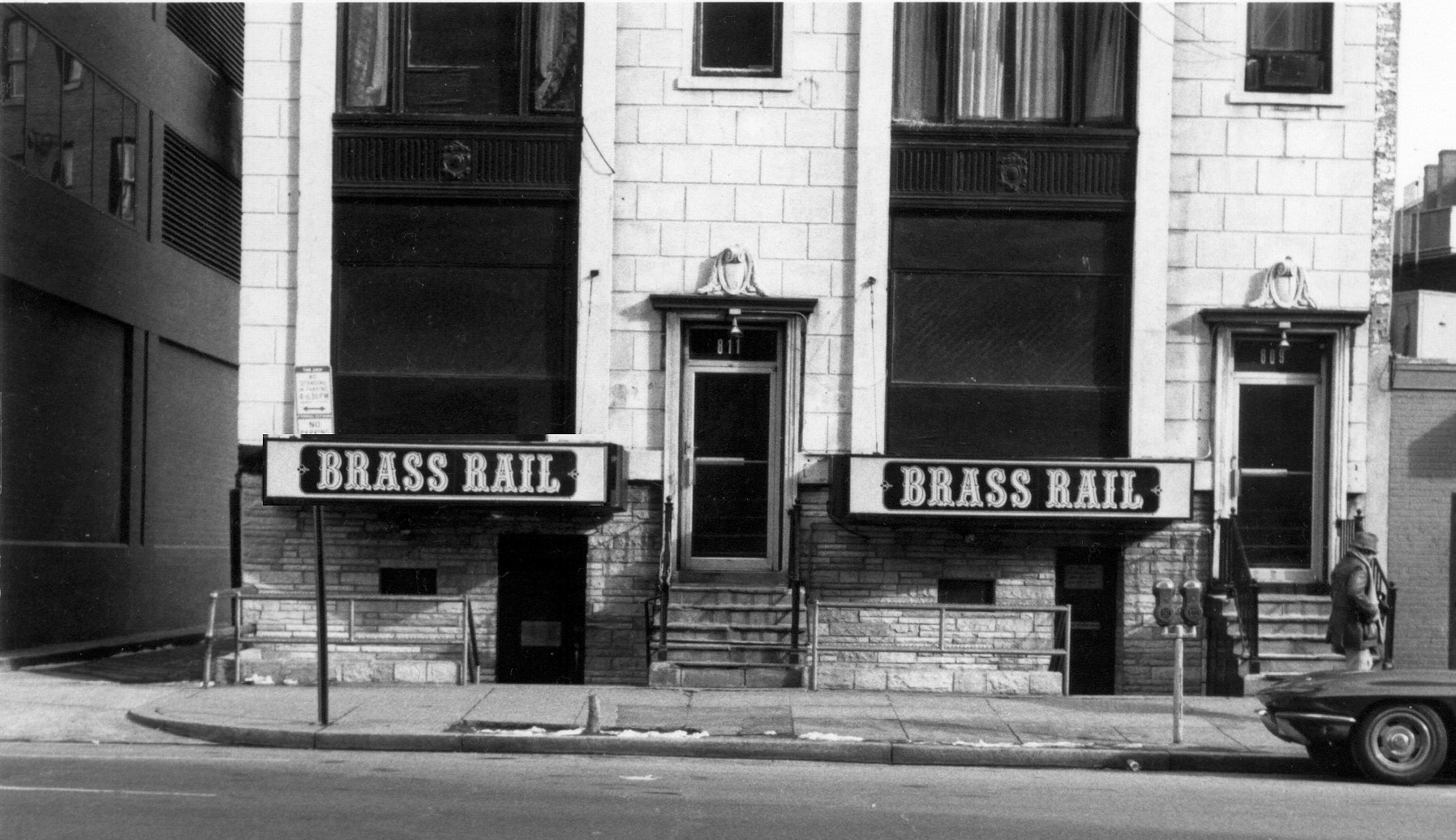

The Brass Rail, 811 13th St. NW, 1967–1996

Name any gay bar that has operated in D.C., and Rayceen Pendarvis has probably been there. The native Washingtonian (who, when asked for an age, coyly responds, “I’m over 50 and under 100”) has been a lifelong advocate, organizer, and noted social butterfly within the local queer community, and has frequented just about every bar on this list.

But there’s always a first.

For Pendarvis, it was the Brass Rail, which opened on 13th Street and New York Avenue NW in 1967. First a biker bar, then a western bar, the Brass Rail seized an opportunity when Annex, a predominately Black gay bar across the street, closed in 1975. Seeing a chance to turn business around, the Rail, as regulars called it, started catering to Black queer people—especially the trans community—with disco, drag, cheap drinks, and queer and trans bartenders.

“Downtown was the place to be, so everyone went to the Brass Rail, even though the girls”—an affectionate term for trans women—“reigned supreme,” Pendarvis says. “I could sit at the bar and I would turn around and look at this beautiful, glamorous woman smoking a cigarette, holding a martini, and having this wonderful conversation with me, and then she would lean over and say, ‘You know, I’m one of the girls.’ And I would be like, ‘Really? Aren’t you breathtaking!’”

The bar became legendary for its drag shows, often put on by the Railletts, an in-house drag quartet that “boasts more beefcake than the Isley Brothers,” as a Washington Post reporter quipped in a 1981 article.

The Rail sat a block away from Franklin Park, which was a buffet of seedy happenings at night, per Pendarvis. “On one end was the transgenders, the drag queens, the gays, and the lesbians. In the middle was the drug dealers. On the other side was the prostitutes and the pimps. And if you could walk through Franklin Park without getting a brick or a bottle or severely read down, and get through to the Rail, you had now passed your initiation.”

Artist and activist Christopher Prince met his first lover at the Rail: An “absolutely stunning” Jamaican Greek model on tour with Ebony Magazine’s Fashion Fair. The bar, for Prince, “was a safe space, before we defined places as such.”

Pendarvis concurs: “The Brass Rail was like home for me. The transgender community was so affirming .… It was a safe place. It was the meeting place. It was everything.”

Part of that safe space feeling came from the bar’s frequent fundraising events to fight AIDS in the ’80s. And, for Budd at least, it was the genesis of her activism. Budd was doing commercial sex work in 1986 when the Brass Rail moved to K and 5th streets NW, where Inner City AIDS Network, a group of predominantly gay men, would recruit gays, sex workers, and trans folks to become HIV peer specialists. Budd was one of those recruits.

That’s the lasting power of these spaces, Budd says: “The gay bar scene helped me to be who I am today.”

1970s

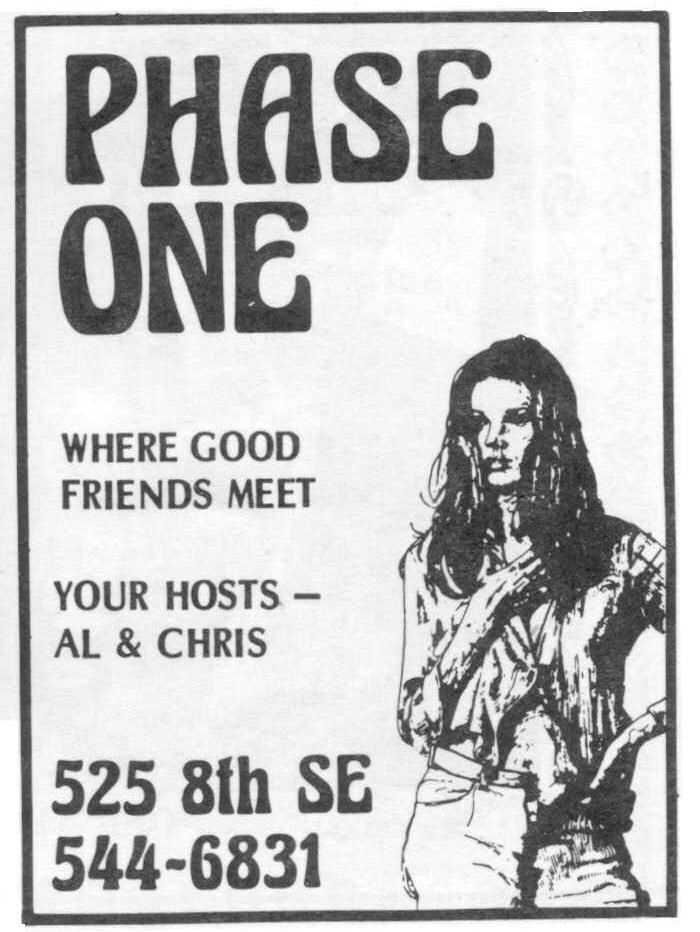

Phase 1, 525 8th St. SE. 1970–2016

Phase 1, pictured left in 2016, has now become a ramen restaurant; Credit: Archer Lombardi; Darrow Montgomery

The first time that Bonnie Morris, then 19, went to Phase 1, a seminal lesbian bar along Barracks Row, she was struck by two things: “A woman offered me drugs, and I was shocked,” says Morris, a historian who spent decades in D.C. Like many gay and lesbian bars of the 20th century, Phase 1 wasn’t in a thriving commercial district. Barracks Row, named after its home to the Marine Corps’ oldest active post, occasionally felt menacing. But it didn’t stop people from coming.

“The other was that there were two women at a table who were clearly in love … holding each other’s faces, and looking at each other with so much tenderness,” Morris continues. “I could not take my eyes off them. I was stunned.”

Phase’s diversity is what struck Morris the most. “There were a lot of women who were in the military and kind of on the down low. There were Black and White women. There were women who were artists, well known in the community, and women who were clearly hard drinkers.”

Local filmmaker and former spoken-word artist Michelle Parkerson noticed the same diversity. D.C. was a magnet for Black queer people in the ’80s and ’90s, Parkerson says. She cites Mayor-for-Life Marion Barry’s administration, which supported both the city’s art scene and its LGBTQIA community, as well as the creation of Black Pride in 1991 as reasons.

But “the remnants of segregation was still alive and well in this community,” she says of her early years out in the mid-’70s. “White folks went to their social hubs. And Black folks, because of the unifying energy of Black Power and Black nationalism, we had our own spaces.”

But lesbians of all ilk found their way to Phase. Though racial tensions—and carding—were more common at gay men’s bars, there were times when “the energy could be a little ‘sketchy,’ as realtors like to say,” says Parkerson, noting that the side-eye from White patrons was especially notable when Black women, who were either single or not dating White women, came out in significant numbers.

“So there was tension in those earlier years, but slowly, at the Phase, it began to equal out, because money is green,” Parkerson says. “The pool tables were there and the bar was there, and the music was okay. So more and more of us started to show up … and the mix began to happen quite naturally.”

The pool table remained a selling point. Jane Martinache, City Paper’s sales operations manager, first visited Phase in the late ’80s to “figure out what gay was and if that was a part of me.” Pool doubled as a conversation-starter.

“I was there almost every night, in the days when I could stay up late, sleep a few hours, go to work, and repeat,” says Martinache. “I made a lot of friends—still have some of them [and] mourn some of them.”

In the early ’90s, Martinache waited at the bar’s all-you-can-eat taco bar. Later, she would pick up bartending shifts.

“I was NOT a good bartender,” she says. “I only knew how to open a beer bottle, to pour a soda, and how to make drinks that had the instructions in the name .… If you were smoking a cigar at the bar, I would ‘accidentally’ spill water in the ashtray when the smoker wasn’t looking.”

Working the bar led Martinache to City Paper. It was there she met and befriended a “7 and 7 drinker” who worked at the paper and encouraged Martinache to apply to a job delivering the alt-weekly’s papers.

She got the job and two years later moved into a full time position. Now, 25 years later, Martinache is the glue that holds this place together, and the 7 and 7 drinker is still one of her best friends.

Club Madame, 500 8th St. SE. 1974–1978

Following Phase 1’s opening, Barracks Row was the place to be for queer women. In the mid-’70s during 8th Street’s lesbian heyday, Club Madame opened, predominantly serving Black women, though Parkerson notes, there was a nice blend of folks on most nights. According to the Washington Blade, Club Madame was meant to be “a cabaret style nightspot offering shows catering toward the lesbian community.”

In ’78, owner BB Gatch rebranded the club as Bachelor’s Mill, which the Rainbow History Project says brought in mostly men. But upon Gatch’s death in 2021, her granddaughter told the Blade that the goal of the rebrand was to make the bar a place “where all LGBTQ could safely come.”

The DC Eagle, 904 9th St. NW. 1972–2020

For almost 50 years, and across four locations, the DC Eagle was the city’s premier gay leather bar. Donning leather and denim, customers (masculine men and bears primarily) flocked to the Eagle for food, drinks, and cruising. It originally opened in 1971 on 9th Street NW, and had two other Northwest stints—all in the heart of downtown. Its final location sat at 3701 Benning Road NE. When it closed for good in 2020, it held the crown as the District’s oldest continuously operating gay bar and one of the oldest leather bars in the country.

Grand Central, 900 First St. SE. 1974–1977

Much like your first kiss, you never forget your first gay bar. For Parkerson, that first bar was Grand Central, which she remembers for its great interior and for playing great music. “Everybody showed up there,” she says. What also made the club special for Parkerson was the surrounding drag clubs. “You had a whole mixture of the gay, lesbian, and nonbinary communities showing up there in the late ’70s.”

Artist Christopher Prince remembers going to Grand Central on a night catered to the Black community. “I was so overwhelmed when I walked in the door, I had to sit down,” Prince says. “I remember that distinctly to this day. And it was decades ago. I had not seen so many Black gay men in one spot, Black men that were gay. I was like, ‘Oh! You mean that I could talk to any of these guys?’ … My friend said, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ I was like, ‘This is gonna take me a minute!’”

The ClubHouse, 1296 Upshur St. NW. 1975–1990

Left: The DC Democratic Party’s cocktail event for Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale at the ClubHouse, circa 1980; Courtesy of Rainbow History Project. Right: Today, the space has been converted into a vet office; Credit: Darrow Montgomery

Sometimes, Prince, 68, would party so late at the ClubHouse that by the time he left, he would see people making their way to church. Rayceen Pendarvis remembers the same thing.

“We would march down Georgia Avenue, wait at the bus stop, or catch a cab, and bypass the church folks. Here come the folks getting ready for church, and we coming from the club,” Pendarvis recalls. “Or some of us would go home and get ready for church. Maybe nod a little bit in church … but we would be there.”

As gay spaces across the city were closing their doors, the party was just getting started at the ClubHouse, an iconic after-hours dance warehouse in Petworth that usually opened around midnight. Started in 1975 by and for the Black queer community, the ClubHouse soon became known as one of the coolest nightclubs on the East Coast, often compared to New York’s Paradise Garage and Studio 54.

To enter, you either needed a highly sought-after membership, or a highly sought-after guest pass. The ClubHouse started with 400 members. At its peak, it had 4,000. “I would always talk my way in,” says Pendarvis, who was eventually given a membership.

It wasn’t that easy for everyone, according to Earline Budd. “We, as transgender women, were turned away,” she says, adding that trans women would sometimes be let in if they were “beautiful” and “slender” enough. “It was the club we all wanted to go to, and we never could get into.”

For those who could get in, the dancing was, by all accounts, spectacular. Celebrities like Lena Horne, Phyllis Hyman, Cheryl Lynn, and Sylvester all performed at the ClubHouse, and even more partied there. To Pendarvis, it seemed that “every major” house DJ in the world “went through the ClubHouse.”

“The music would take you to another place,” Pendarvis says. “We would jump off the balcony onto the speakers, and off the speakers into splits. Honey, Dancing with the Stars had nothing on us.”

“The ClubHouse would get so packed, and the energy of it would get so high, that you would come out of it soaked,” Prince says. “Your underwear would be wet, and I am not exaggerating. … Some people would take a change of clothes.” Pendarvis concurs: “You’d go in like Clark Kent and come out like Wonder Woman.”

The club hosted a number of events throughout the years, but none as popular as the Children’s Hour, an invitation-only Memorial Day weekend extravaganza that eventually evolved into D.C.’s Black Pride, one of the first in the country. A notorious punch (nicknamed “electric punch,” “magic punch,” or, less discreetly, “acid punch,” depending on who you talk to) would make its way around. “The electric punch would go really fast,” Prince says. “If you got there in time, your night was set.”

It also hosted tons of community fundraisers and political affairs, including campaign events for Mayor-for-Life Marion Barry and Walter Mondale. In the ’80s, as citywide efforts to combat the AIDS epidemic routinely neglected Black Washingtonians, the ClubHouse, under the management of Rainey Cheeks, became an essential organizing space for Black gays and lesbians. Us Helping Us, which was co-founded by Cheeks in 1985, held its first meetings at the ClubHouse.

“It was a wonderful experience, seeing how we rallied as a community in the ClubHouse,” says Pendarvis.

The Delta Elite Social Club, 3734 10th St. NE. 1976–2014

When you hear a glamorous name like the Delta Elite Social Club, a strip mall probably isn’t the first location that jumps to mind. But that’s exactly where this after-hours dance club operated. For nearly 40 years, the Delta Elite was a beloved institution for D.C.’s Black queer community, offering late night dancing and performances in a Brookland strip mall.

The Delta, as regulars called it, was Pendarvis’ neighborhood spot. “When I think of the Delta Elite, I think of dancing on the speakers to ‘Let the Music Play,’” Pendarvis says. But it was also a spot that hosted fundraisers to combat the spread of HIV, and with its dance floor, a raised DJ booth, and a lounge area in the basement, the Delta held events for straights, gays, and lesbians.

Tina Bradley, a Black queer educator and burlesque performer who moved to D.C. to attend Howard University in 1994, remembers dancing the night away to hip-hop and house at the Delta, and witnessing some of the most extraordinary strippers she’s ever seen.

“If you were out there, you had body. You had hips, you had ass, you had tits … you were giving something .… It was sass, the way you carried yourself, the confidence. And it was tricks,” Bradley says. “These women were athletes. This was not just, ‘Oh, you know, I’m shaking a little bit, putting a little bit in your face and doing a little tease’—no. These were workouts.”

1980s

Badlands, 1415 22nd St. NW. 1984–2002

By the early ’90s, the intersection of P and 22nd streets NW was a gay mecca. Badlands was there, but so was the Fireplace, and Fraternity House (which rebranded as Omega in 1997). Today, Fireplace, sold to new owners earlier this month, is the only one still standing. But when D.C. native and co-owner of Little Gay Pub, Dito Sevilla, was coming out, Badlands’ convenient location just west of Dupont Circle made it popular among the city’s college-age patrons.

“Part of the story, when people ask [about our favorite gay bars], I think you miss your 20s—when you first came out,” Sevilla says. “So whatever age you are, is whatever bar that was. For me, Badlands—that became [another gay bar] Apex [before becoming Phase 1 of Dupont in 2012], which became all businesses and condos—was the most memorable.”

The Pub owner remembers Badlands as a “clubby gay bar that played music videos.” In fact, videos were a major part of Badlands, where televisions playing porn hung over the bar’s urinals. On the weekends, the upstairs space opened up while downstairs consisted of a bar near the entrance, a dance floor, and a lounge. In the back sat another doughnut-shaped bar, where “everyone could sort of stare at each other from across the room and flirt,” says Sevilla. “It was just a very kooky space.”

But more than kooky, Sevilla emphasizes Badlands’ (and Apex’s) liberating vibe. “For [some of] these kids … this is the first time they’re in the city where they can be gay and it’s sorta not a big deal .… Badlands/Apex was a very free space where you didn’t feel like being gay was weird. You didn’t feel like being gay was so shocking. It was just the way everybody was.

“It really was a very young space where people celebrated youth in a way that was—I don’t want to say innocent, but it wasn’t salacious,” says Sevilla. “It was just … a very fun, young gay place.”

Hung Jury, 1819 H St. NW. 1984–2002

The gay bars of D.C.’s past were not only spaces for dancing, drinks, and wild celebration. Sometimes, they were the only places where the community could mourn.

When Matthew Shepard was beaten, tortured, and left for dead outside Laramie, Wyoming, in 1998, Bonnie Morris, 63, was working as a professor at George Washington University. In response to Shepard’s murder, Morris went off script during a lecture. Instead she spoke about the history of gay oppression in this country.

After she wrapped, a student approached her to invite her to have a drink with the GW women’s rugby team. “If you’re all over 21, I’ll meet you at the Hung Jury,” Morris recalls saying.

Tucked behind a mysterious blue door in an unassuming alley off of H Street NW, the Hung Jury became a fixture in the lesbian bar circuit soon after it opened in 1984. The popular spot had a pool table, a lounge area, and two bars. But its main attraction was its dance floor, which was packed on weekends. Reportedly, the Hung Jury only admitted women, or people who were accompanied by one. In 1996, it hosted the city’s first ever drag king competition.

Tina Bradley would often go dancing there alone, since her closest friends in the ’90s were straight. She remembers an eclectic, racially diverse crowd, thumping house music, and lots of attractive women. “I did a lot of flirting there,” she says. “I used to just get lost on the dance floor.”

It was never June Thomas’ favorite bar, but it was “the best place to go on the weekend if you wanted to dance,” says the journalist and author of A Place of Our Own: Six Spaces That Shaped Queer Women’s Culture. “It was actually a decent place once you were inside .… The music was always a bit meh, but you could actually see women’s faces, because it wasn’t too dark.”

Located just two blocks away from GW’s campus, Hung Jury was popular with college kids and young women who went on to make a dent in popular culture. Morris confirms filmmakers Maria Maggenti and Jeanette Buck attended along with Elizabeth Ziff of BETTY (creators of The L Word’s theme song). “We were all like 23, before any of us had gone on to be famous,” says Morris.

La Cage aux Follies, 18 O St. SE. 1984–2003

Left: La Cage aux Follies, 1984 to 2003, formed part of a once-thriving gay nightlife circuit in Navy Yard; Courtesy of Rainbow History Project. Right: today, it’s part of Nationals Stadium; Credit: Darrow Montgomery

In 1990, 22-year-old Craig Seymour hadn’t mustered up the courage to visit a gay bar. But when he read in the Blade that his favorite porn star, Joey Stefano, would be performing at La Cage aux Follies, he knew he couldn’t miss it for the world.

“You couldn’t just watch porn on your phone, you actually had to go to a video store, rent a video cassette, and take it home. So there was a lot of investment in it, you know?” Seymour says. “He was such a big star in my eyes .… I had to go, and see this person in the flesh. Literally.”

Thirty-four years later, Seymour still remembers that night in juicy detail. “It was so liberating to be able to freely look at guys that are naked,” he says. “It implicitly sent the message that there was nothing wrong with looking at other guys .… There was nothing wrong with being queer, because here I was in a room full of other guys doing the exact same thing.”

When he says naked, he means naked. This was before the D.C. Council banned nude performances in bars and clubs for a number of years. Today, nude dancing is permitted, as long as it’s on a stage and “at least 3 feet away from the nearest customer.” Back then, gay strip joints like La Cage—which later became Heat—as well as Follies, Wet, and Secrets, were filled with “completely naked, completely hot guys” who would get well within three feet of tipping customers, Seymour says.

“It felt like belonging,” says Seymour, who worked as a stripper for a few years in college (detailed in his memoir, All I Could Bare). “The sense of community was so different from spaces where it was about hookups, because then you’re being judged. … The strip clubs were free from all of that, because the strippers were the focus. That really allowed me to have genuine conversations and friendships with people that weren’t based around attractiveness, age, or all of those things that divide people.”

In the ’90s and early 2000s, Heat, Follies, Secrets, Wet, and other gay nightlife spots were all within walking distance of each other, making Navy Yard a “queer candy store” in Seymour’s memory. Back then, the neighborhood was largely considered undesirable, meaning the gay-oriented businesses that resided there were largely left to do as they pleased.

That changed in 2005 when the city invoked eminent domain to make way for a new attraction: Nationals Park. The urban redevelopment process that followed brought Navy Yard’s thriving gay nightlife scene to an abrupt end.

“It was just a fantastic queer ecosystem of drag queens, and strippers, and different races and ethnicities,” Seymour remembers. “There’s never been anything like it since.”

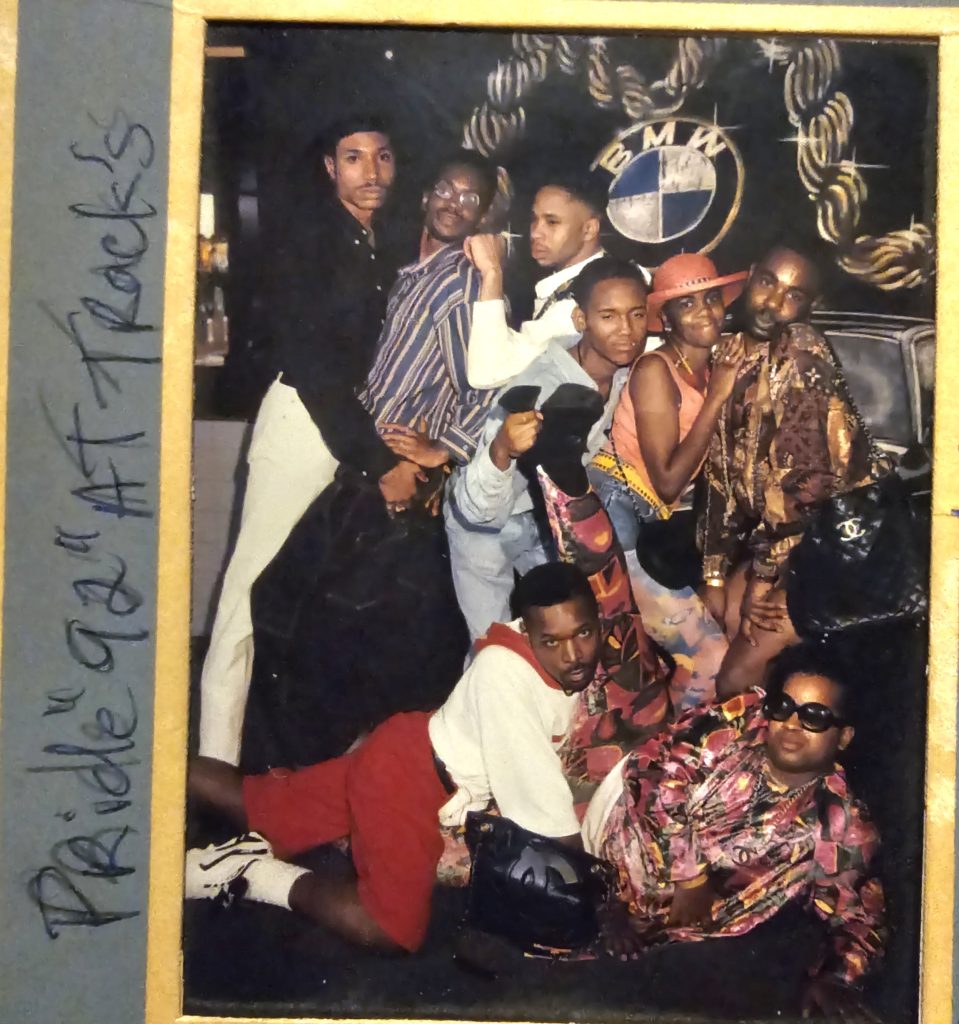

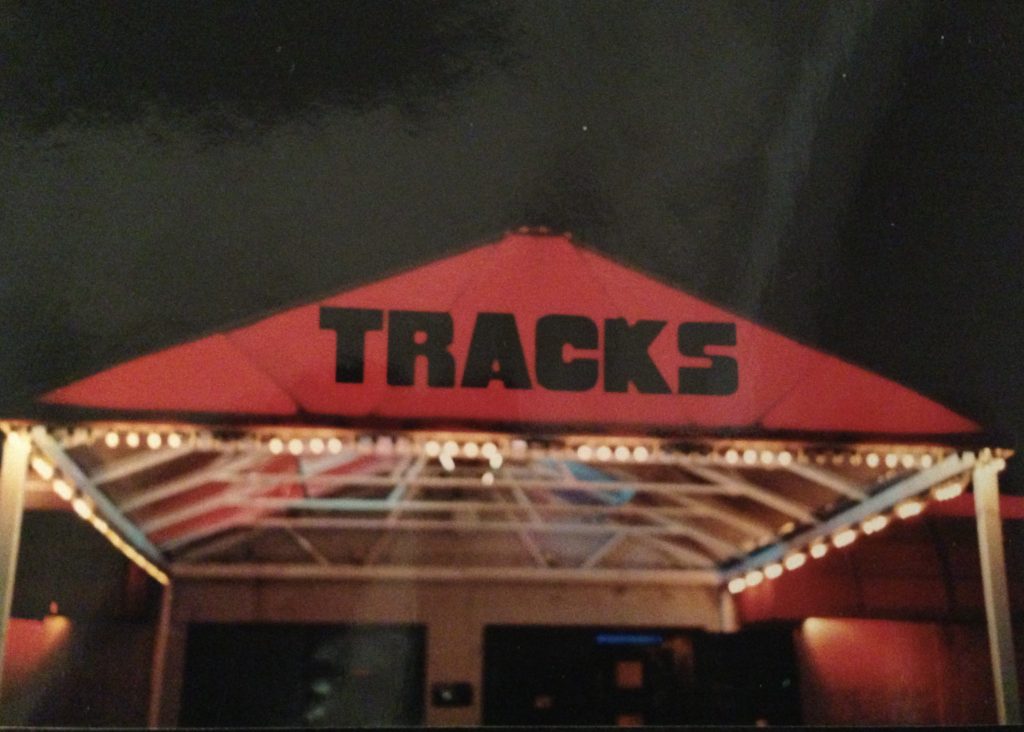

Tracks, 1111 First St. SE. 1984–1999

Ed Bailey wasn’t out the first time he went to Tracks, but it was so cool, even his straight friends wanted to go. “There were thousands of people. It was incredible and overwhelming and ridiculous and scary and exhilarating,” Bailey says of his first visit to Tracks as an 18-year-old. “I was like, ‘Oh, there are other gay people.’”

Then, as if the night wasn’t already memorable enough, the power went out. “It was very scary,” Bailey recalls. “But everybody put their lighters on … and started banging on the walls and stomping with their feet to make a beat so people could keep dancing. And they were chanting: ‘We don’t need no power.’” When the lights and music eventually came back on, the club “went crazy,” says Bailey.

He was hooked for life. “I think I went back to Tracks every day that week,” Bailey says. Today Bailey is a popular DJ and, with his business partner John Guggemos, a primary architect of D.C.’s gay nightlife scene. Together, they’ve owned and operated Trumpets, Cobalt, Halo, Town, and Trade (still open today) among others. All those ventures, he says, can be traced back to that first night at Tracks: “That’s where my career started.”

Tracks was—as nearly everyone we spoke to stressed—legendary. A huge nightclub with a massive dance floor, a room that played music videos, and an outdoor volleyball court, Tracks “had something to hold your attention wherever you were,” says Bailey.

“It was like a playground,” says Seymour.

“Honey, it was the place to be,” says Rayceen Pendarvis.

In the ’80s and ’90s, while some of D.C.’s prominent gay bars still operated with blatantly racist policies, Tracks catered specific nights to different communities. On Sundays, Seymour says, Tracks would fill up with Black gay men.

“There were so few places where masses of Black gay men could get together, because at the other big dance clubs, Black gay men were few and far between,” says Seymour. “It was a very nurturing, warm experience of Blackness.”

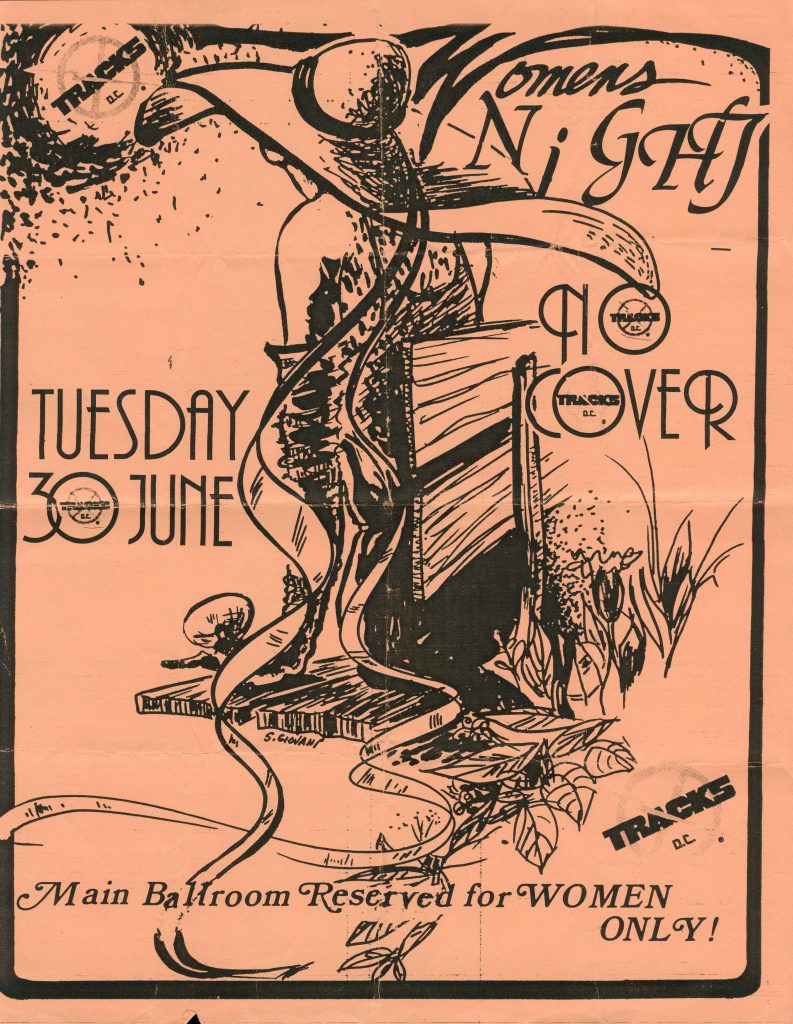

The last Tuesday of the month was women’s night, as June Thomas recalls. “I was mad that they gave us so little and on such an obviously undesirable night,” Thomas says over email. But, she adds, “The benefit of only having one night a month meant that everyone knew exactly when to show up.”

Tracks also became a site for community events. As Michelle Parkerson puts it, bars worked “double, triple duty sometimes, because they were our own spaces.” She remembers one fundraiser—likely for Roadwork—where Toshi Reagon performed. “It was early in her career, she was still a teenager, but fierce already,” Parkerson says.

According to Bailey, Reagon wasn’t the only celebrity who performed at Tracks: RuPaul, Blondie’s Debbie Harry, and Pete Burns of Dead or Alive graced the stage, too. One night, Depeche Mode showed up after playing a concert to dance. Cora Masters Barry, Marion Barry’s widow, was known to frequent the bar.

The superstars partied alongside the college students, like Tina Bradley. “Tracks felt hedonistic,” she says. “People would get naked at Tracks, no problem. There was a freedom, and it was just the best.”

The club went on until 1999, when the space was sold to developers. “Tracks closing was a monumental thing that happened in D.C. It signified the end of an era,” says Bailey. “It was incredibly important. It was the reason people survived.”

Hill Haven, 516 8th St. SE. *1989-1993/94

For several years, the lesbian bar Hill Haven sat between Bachelor’s Mill and Phase 1 along 8th Street SE. The bar, which took up the second and third floors of a still-standing historic building, became a predominant Black lesbian space. Michelle Parkerson remembers the bar being run by a Black lesbian, but according to the Rainbow History Project, Black lesbians boycotted the club over accusations of racism in 1991. That same year, RHP reports, it came to light that Hill Haven was not lesbian- or even woman-owned—“contrary to its advertising.” But countering that claim, the November 1994 issue of the Women in the Life newsletter, reported on the bar’s closure, naming Judy Douglas as the club’s “longtime proprietor.” According to the article, the Advisory Neighborhood Commission targeted only Hill Haven despite it being one of several queer bars along Barracks Row and campaigned for the bar’s closure. But during its run, the bar was one of the first venues where Onyx—a dance troupe of Black lesbian and sexually expansive women—performed, says Parkerson. “Lots of folks became fans and just packed the crowds,” she recalls. “I loved Hill Haven … just because it was so woman focused.”

1990s

El Faro, 2411 18th St. NW. 1991–1995

When Jose Gutierrez moved to D.C. in 1993, discriminatory practices were still common in the gay bar scene. “In some bars, they were asking Latinas and Latinos to have two IDs,” says Gutierrez, a historian of Latine LGBTQIA culture. “For some people, they asked only for one.”

That’s what made El Faro, which opened in Adams Morgan in 1981, so special: It was the first bar in D.C. operated by and for the queer Latinx community. “For the first time, we had a safe space,” Gutierrez says. “It was a sense of security, a sense of family.” On Saturdays, Latina drag queens would put on a show in the “really small” and “always packed,” bar, says Gutierrez. For a quarter, you could play your favorite salsa or cumbia on the jukebox.

Escandalo, 2122 P St. NW. 1994–1997

By the time El Faro closed (following an uptick in violence, per the Rainbow History Project), queer Latines had already begun to migrate to the more spacious Escandalo, a mixed Latino bar that opened in 1994 at 2122 P St. NW (the same address used for the Frat House and Omega, though it was technically in the alley).

Escandalo “was like a community center,” Gutierrez says. On one side, a restaurant served up fresh chicharrón, pupusas, and tacos. At the bar, margaritas, Coronas, and aguas frescas were standard. Cumbias, salsas, and rancheras played on the loudspeakers, and drag queens, musicians, and poets took the stage for regular performances. “It was a big, big place,” Gutierrez says. “People who was lost, or needed an LGBTQ space, they could come to Escandalo.”

In 1997, Escandalo closed, but was soon replaced by Deco Cabana, another Latine gay bar, which stayed open until 2000.

Queer Latinos would also congregate at parties hosted throughout the city by ENLACE, D.C.’s first advocacy group for the Latine LGBTQIA community. Letitia Gomez, a longtime lesbian activist who headed ENLACE for a number of years, remembers talking to a gay Latino man at one of the group’s final parties in the ’90s, hosted on the top floor of a Mexican restaurant in Capitol Hill—the same place that was Club Madame and Bachelor’s Mill and is now As You Are.

“He said he wanted to start a club,” Gomez recalls. “That club ended up being Escandalo.”

Circle Bar, 1629 Connecticut Ave. NW. 1994–2000

It’s tough for Wayson Jones to name his favorite local gay bar. “I’ve been to so many over the years,” says the artist and D.C. native. He liked Brass Rail, the Eagle’s four locations, and the Fireplace.

But a simple math equation leads Jones to his favorite: “According to my metric (number of good times divided by number of visits), it would be the Circle Bar.” Right in the heart of Dupont, he remembers the three-level nightlife hub for being comfortable—“not a dive, but not fancy”—and for its large, street-level windows. In the early days of gay bars, windows were a risk few dared to take. They were boarded up or blacked out to ensure the safety and secrecy of their clientele. “The visibility was nice,” says Jones. “Having it there while the Lambda Rising bookstore was still around gave this feeling of ‘gay establishment’ that I appreciated.”

He remembers the bar’s diversity when it came to race if not gender. But his favorite memory revolves around a bar game: “The best pool shot I ever made playing doubles with my friend Cherisse, 8-ball in the corner, diagonal the length of the table FTW.”

Though Jones isn’t sure why Circle closed, he suspects gentrification had something to do with it. “My first reply,” he writes via email: “‘Because straight white people took over the neighborhood,’ but there may have been other circumstances.”

Omega, 2123 Twining Court NW. 1997–2012

Omega, which was originally called the Fraternity House (1976-1997), sat behind Badlands in the alley at 21st and P streets NW. “That place had porn on the floor,” says Dito Sevilla. “It had TVs built into the floor, an upstairs room that played porn, and ridiculous, horrible drag shows on Monday nights.” The address, once synonymous with gay debauchery in the District, is now condos; Sevilla ponders: “Do [the current residents] have any idea what was going on here?”

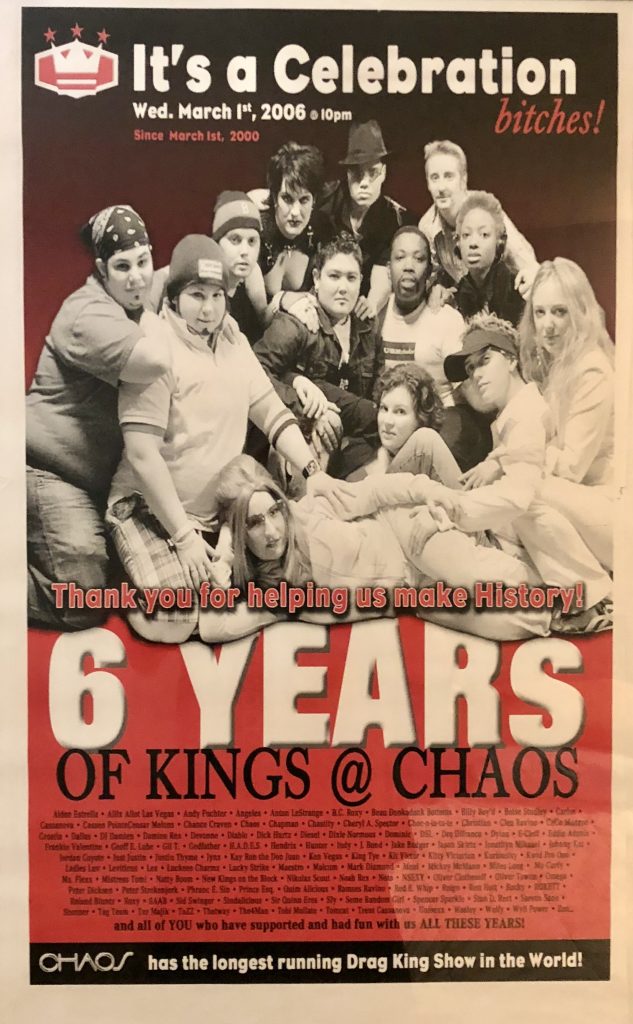

Chaos, 1603 17th St. NW. 1998–2008

When it comes to drag kings, Chaos takes the crown. Opened in the Dupont space that previously housed Trumpets and Q Club, Chaos was known for its Latin nights and hosting the city’s only regularly scheduled drag king show, pioneered by the king of drag kings, Ken Vegas.

“Chaos emerged in the period where there was a prolific drag king culture, a spoken-word culture, and even a burlesque culture, in the lesbian community,” says Bonnie Morris, who was involved with spoken-word group mothertongue. One Wednesday a month, mothertongue would perform at the Black Cat, then everyone would head to Chaos to catch the drag show, Morris recalls.

“The kings would come out and hand out Tootsie Rolls or lollipops to the crowd, and come and sit on your lap and be flirty,” Morris says. “I’ll never forget … the look on the faces of some women when that happened for the first time.” It wasn’t all seduction and sex, though. “They did some very moving political skits about being queer baited and gay bashed as younger people … there was a political sophistication to what we were seeing.”

Chaos was also a place where the gay Latine community congregated, according to José Alberto Uclés, a stylish socialite and longtime local advocate for the LGBTQIA community. “You saw us everywhere,” he says. “It’s a different energy, listening to the language, and all the different accents and colloquialisms .… To me, a gay bar is where you find your community. And if the bar is accepting, it makes it so much more fun.”

2000s

Lizard Lounge, 1520 14th St. NW. 1223 Connecticut Ave. NW, 1998–2006

Queer as Folk premiered on Dec. 3, 2000, and forever changed gay culture. It also changed Sunday nights in the District. For 45-year-old Dito Sevilla, Queer as Folk watch parties became a pregame for the weekly early-aughts party Lizard Lounge, hosted by “nightlife legend” Mark Lee.

“It was an iconic Sunday evening event,” says Sevilla. The party originally took place at Saints, which eventually became Estadio and just reopened as Bar Japonais. Aside from the bar and dance floor, where ethereal house music played, a lounge area “allowed you to make out with people and have clandestine experiences,” says Sevilla.

Outside, at 14th and Church streets NW, it was not the trendy hub it is today. “Lizard Lounge was on a street that nobody dared go to,” says Sevilla. “Church, which was not a street, but an alley, was dangerous.” But once inside, the party was an “oasis paradise,” Sevilla continues. “It was a place where you picked your outfit on a Thursday to go there.”

And nothing would shut Lizard Lounge down. “Lee did not close for any reason—there could have been an apocalyptic storm—he did not close and the staff would show up,” Sevilla says, recalling one Sunday after Lizard Launch relocated to Connecticut Avenue when a massive snowstorm hit D.C.

As Sevilla and his friends walked into the party, another couple arrived—on skis.

“This couple—in full ski suits—on their skis and Mark Lee, without skipping a beat, without even looking surprised, says, ‘Gentleman, may we check your skis,’” Sevilla remembers. “He gave them tickets for their skis and in they walked, pseudo shirtless with these ski outfits on. It was one of these quintessential nightlife experiences that you never forget.”

Like all iconic parties, this one too came to an end as other gay bars opened, competing for Lizard Lounge’s crowd, but the nail in the coffin? D.C.’s ban on smoking inside. Lee, like many bar and restaurant owners, opposed the ban.

“He thought it was going to kill nightlife as we know it and people were gonna have to go outside and be pariahs,” says Sevilla. “He said, ‘We’re never doing the party again.’ He was good to his word. The party never happened again.”

BeBar, 1318 9th St. NW. 2006–2009

The short-lived Shaw bar, which, according to the Rainbow History Project, faced protests from Black churches upon opening, played a role in the origin story of local queer DJ collective Anthology of Booty. One member of AoB, Darby Hickey aka DJ bent, tells City Paper: When Chaos closed, local king and event promoter Ken Vegas moved his drag and burlesque night to BeBar. Vegas asked DJ Natty Boom to play and she brought in a crew from Radio CPR that would go on to form Anthology of Booty (made up of Natty Boom, bent, Mothershiester—aka Slammer, Kristy la rAt, and Indanile).

“We were all part of the station and throwing [fundraising] house parties together,” says Hickey. Those house parties came to a natural end after Hickey and Mothershiester hosted one with 400 attendees. “That wasn’t sustainable for our houses,” says Hickey.

Hickey remembers the nights at BeBar as being “some pretty epically debaucherous times.” Asked to spill the tea, Hickey replies: “I’ll say sex and drugs and leave it at that.” It also helped ignite AoB’s creation.

As DJs, the AoB team created a space with queer vibes and different music from the gay bar “pop jams.” But one night stands out to Hickey: Grind the Vote.

“At that time I was doing a lot of sex worker organizing, and we held an event in the summer of 2008 with … Different Avenues, HIPS, and the sex worker magazine SPREAD, which featured exotic dancers and other sex workers and was a great time, creating space for those often pushed to the margins.”

Town Danceboutique, 2009 8th St. NW. 2007–2018

Town opened its doors the same year the iPhone launched. In early 2008, Lady Gaga released her first single, “Just Dance.” Ke$ha’s “Tik Tok” debuted the following year. So did RuPaul’s Drag Race, Uber, and Grindr. Barack Obama was president—though it would be a few years before he publicly supported marriage equality.

“It feels like a moment, right? It feels like a lot of things happened that are now just part of our life,” says Ed Bailey, who co-owned Town with his longtime business partner John Guggemos. “It was this amalgamation of the beginning of where we find ourselves right now with pop music, and phones, and apps. Town was right there, as we grew into that.”

Town was located right off of Florida Avenue NW. “When we started … we were like, ‘Do you think people will come here?’” Bailey says. Today’s young people would probably scoff at the notion that he was once skeptical about opening a nightclub in Shaw. “But that was a concern,” he says. “It was dicey, but that’s where those kinds of clubs needed to be.”

If people were concerned about their safety, it didn’t show: Town was a hit from the start. “We tried to take all of the things we’d learned at all the places we’d been, and put them all into this one thing,” Bailey says. “I wanted Town to be a place that does for other people what Tracks did for me,” Bailey says.

And like Tracks, Town also provided sanctuary for the queer community to mourn and celebrate. “The week that marriage equality made it through the Supreme Court, thousands of people showed … and partied all night,” Bailey says. A year later, following the Pulse nightclub shooting, thousands of people showed up again. The message, to Bailey, was clear: “We’re not letting something like that keep us from going out and being with each other.”

The party came to an end in 2018, when Town was converted into the luxury apartment complex that stands there today. Big warehouse-style gay clubs like Town “don’t exist much anymore,” says Bailey, and he’s often asked why. “I always say, the number one reason is real estate development .… It’s not a signal that the community has changed, or that we don’t need those spaces anymore, or it’s Grindr’s fault .… The real estate goes away; when that goes away, there’s no opportunity to do this.”

Bailey has overseen a lot of openings and closings throughout his career, but shutting down Town was extra tough, he says: “I miss Town all the time. I just liked going there.”

2010s

The 2010s brought more closings than openings: Dupont’s Cobalt shuttered in 2019, less than a year after Town turned out the lights. When Phase 1 went dark in 2016, it marked the first time in 46 years that Barracks Row wasn’t home to a queer bar. Another six years passed before someone picked up the torch: As You Are opened in the former Club Madame and Bachelor’s Mill spot at 500 8th St. SE.

Of these closures, the loss of Phase hit me, City Paper’s Sarah Marloff, harder than expected. The lesbian dive, though not the coolest spot in its final years, played a critical role in my life. I met my now-wife on Phase’s dance floor in August 2011—she may have been wearing an eyepatch at the time. A month later, during the bar’s annual Phasefest, I met one of my closest friends, Christina Cauterucci (a City Paper alum). And, somewhere along the way, we fell in love with queer space-making. Looking back it’s impossible not to credit the gay bars that came before us, took us in, and introduced us to our communities.

At the end of the party—when the spilled drinks are mopped up, and the porn is turned off, and the lights come back on, and the music stops, and the building becomes a condo/ramen bar/WeWork—that’s what we take away from these spaces. The memories, the friendships, the feeling of belonging and those joyous moments on the dance floor. The bars evolve as we do. They come and go and sometimes come back again. The spaces may be fleeting, but what they’ve given us is permanent.

Editor’s note: Some dates have been flagged with * to indicate contradicting dates from various sources.