Lauren Yee may not be the most performed playwright on a national level, but she has had an impressive run here in the DMV: In less than 12 months, Arena produced her Cambodian Rock Band last summer, King of the Yees ran at Signature Theatre in October, and now her 2013 play The Hatmaker’s Wife has come to Theater J.

Using magical realism to explore the Yiddishkeit world, The Hatmaker’s Wife takes place in one suburban house in two different eras. In the past lives Hetchman, the eponymous hatmaker (Maboud Ebrahimzadeh), Hetchman’s Wife (Sue Jin Song), whose name has been forgotten due to years of either being addressed as “you” or being referred to as “Hetchman’s wife,” and Hetchman’s beloved red velvet Homburg hat. Hetchman has retired from millinery—having locked up his workshop, he’s decided to spend the remainder of his years planted in his easy chair, Homburg on his head, scratching where he itches, blowing his nose and always missing the wastepaper basket, and watching a World Without People on television. All this happens while he ignores his wife working around the house. Ebrahimzadeh does a master class in mining, putting the maximum effort into laziness for physical comedy. One day, his hat falls off his head, and soon after, his wife disappears as well.

Years later, after Hetchman is gone (or is he just napping unnoticed?), a young couple moves in: Ashley D. Nguyen, who played a fictional version of Yee in Signature’s King of the Yees, is an unnamed woman identified in the playbill as “Voice,” a copy editor of safety manuals. (A curious motif of The Hatmaker’s Wife is that the only women in the play with names never appear on stage.) Joining Voice is her boyfriend, Gabe (Tyler Herman), a schoolteacher. The wallpaper has not changed, nor have the portraits that hang on the wall; even the easy chair remains. Scenic designer Misha Kachman has fun dropping clues that the house is strange with slightly angled attic crawl spaces filled with jars, urns, and flowerpots, some of which have mysterious glowing contents. It’s a fantastic world, filled with grime, crumbs, and schmutz.

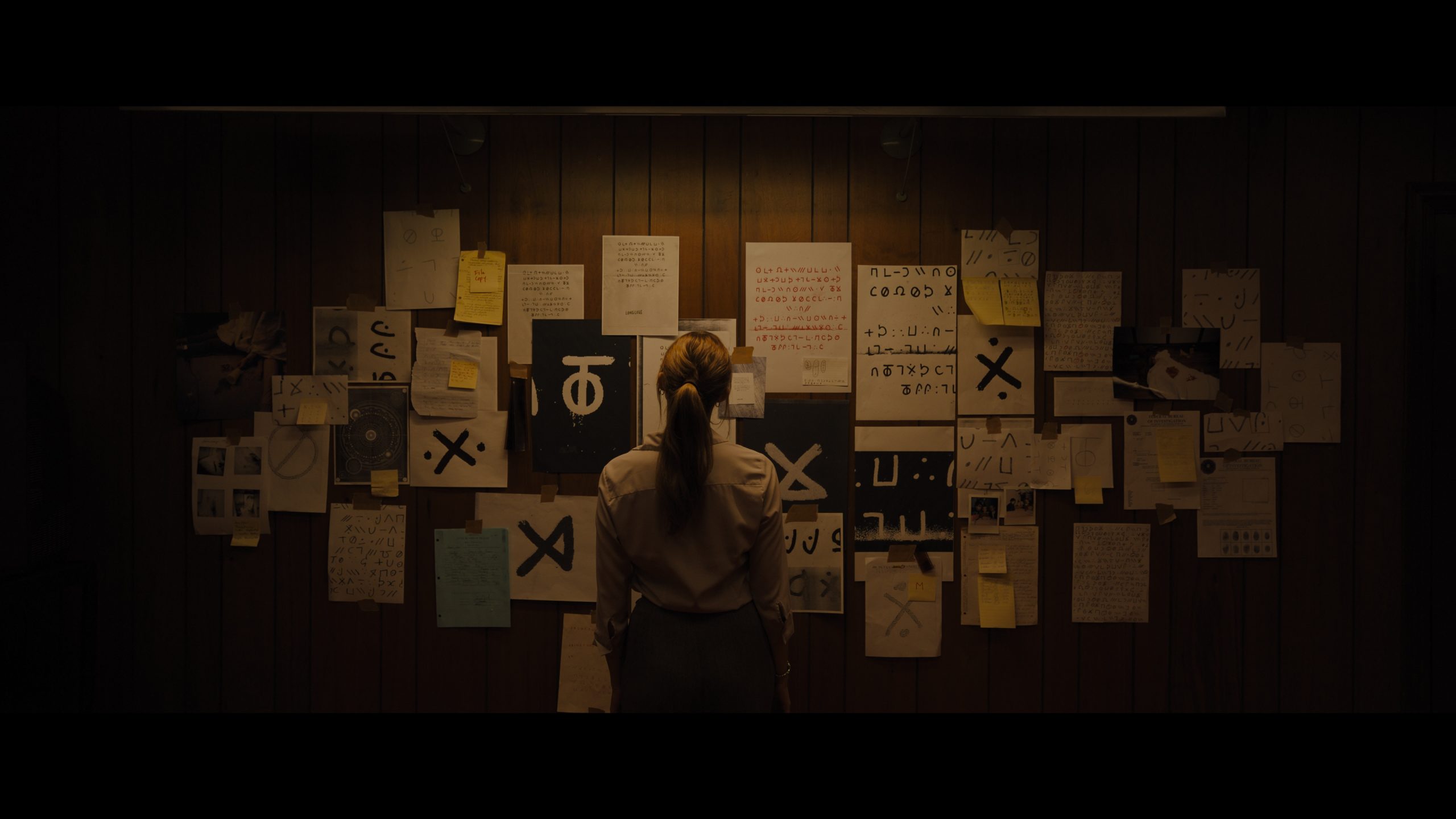

While other plays have been structured around alternating scenes depicting different eras in a single location—Tom Stoppard famously used this structure in Arcadia, and a recent area production of Beth Kander’s Hazardous Materials used it to explore identity and broken hearts. Yee, however, bridges her two eras with magical realism. The young copy editor picked the house because it spoke to her, literally, the enthusiastic living room wall speaks to her (voiced by performance artist and clown Alex Tatarsky, whose eccentric delivery of such lines as “I am wall-of-truth! So awesome!” are wonderfully mad). As an observer of all that happens in the house, the wall has been writing a story about the love triangle between Hetchman, his wife, and his hat, periodically dropping new pages on Voice, so that she can read and edit the manuscript, thus making her the “voice” of the narrator. Meanwhile, her obsession with the manuscript is causing Gabe to feel neglected.

The increasingly reclusive Hetchman has one last remaining connection with the human world: Meckel (Michael Russotto), his neighbor and childhood best friend. Meckel is an emotionally expressive widower, lover of other people’s wives, and “everyone’s favorite grandparent” who helps demonstrate a principle of the play’s metaphysics: People are grounded by love and without enough of it, they literally float away.

Meckel suggests Hetchman write a letter to his missing hat. In this world the U.S. Postal Service can find anyone or anything for the cost of a postage stamp. Of course, the hat is with Hetchman’s wife, who was not just fed up with doing the housework, but her husband’s refusal to make her a hat. Since disappearing, she has been traveling from hatmaker to hatmaker in search of someone with the skill to copy her husband’s work.

Meanwhile, a golem, played by Herman, unexpectedly shows up at Hetchman’s home. As with most of its representations in Jewish folklore and myth, the golem seems ready to provide assistance and companionship, but it’s inarticulate and unable to explain its purpose, though it seems hungry for the same snack foods Hetchman favors. Since neither Hetchman nor Meckel called it into existence, they can only guess at why it’s been summoned. Herman gives a hilarious, shambling performance underneath the crude form, created by costume designer Ivania Stack in the form of a giant doll made of muck, with depressions where its facial features should be.

King of the Yees, which also makes use of magical realism and absurd comedy, at points casts a critical eye on the gentrification of America’s Chinatowns, but The Hatmaker’s Wife is a little gentler toward that issue. Voice and Gabe, a young couple who recently left the city, are gentrifiers, having moved into a suburb that is still home to a Jewish American community only a couple of generations removed from the now-extinct Yiddish-speaking communities of Europe, but there’s no notion that they are displacing anyone in the process.

The plot structure is a great deal looser, and the political stakes are a great deal lower in The Hatmaker’s Wife than in the other recently staged Yee plays. But here Yee stacks one fantastical element after another: a know-it-all wall with literary pretensions, mustache-wearing architecture, swaddled babies who fly away upon neglect, a snacking golem, glowing jars filled with lost memories, and the most efficient postal system in human history, in order to create a world of increasingly comic absurdities. (Before seeing this, I had not laughed so much at the theater in months). Nonetheless, director Dan Rothenberg, along with the cast, creates a magical world filled with heartbreak and sadness.

The Hatmaker’s Wife, written by Lauren Yee and directed by Dan Rothenberg, runs through June 25 at Theater J. theaterj.org. $39.99–$90.99.