“It feels like church.”

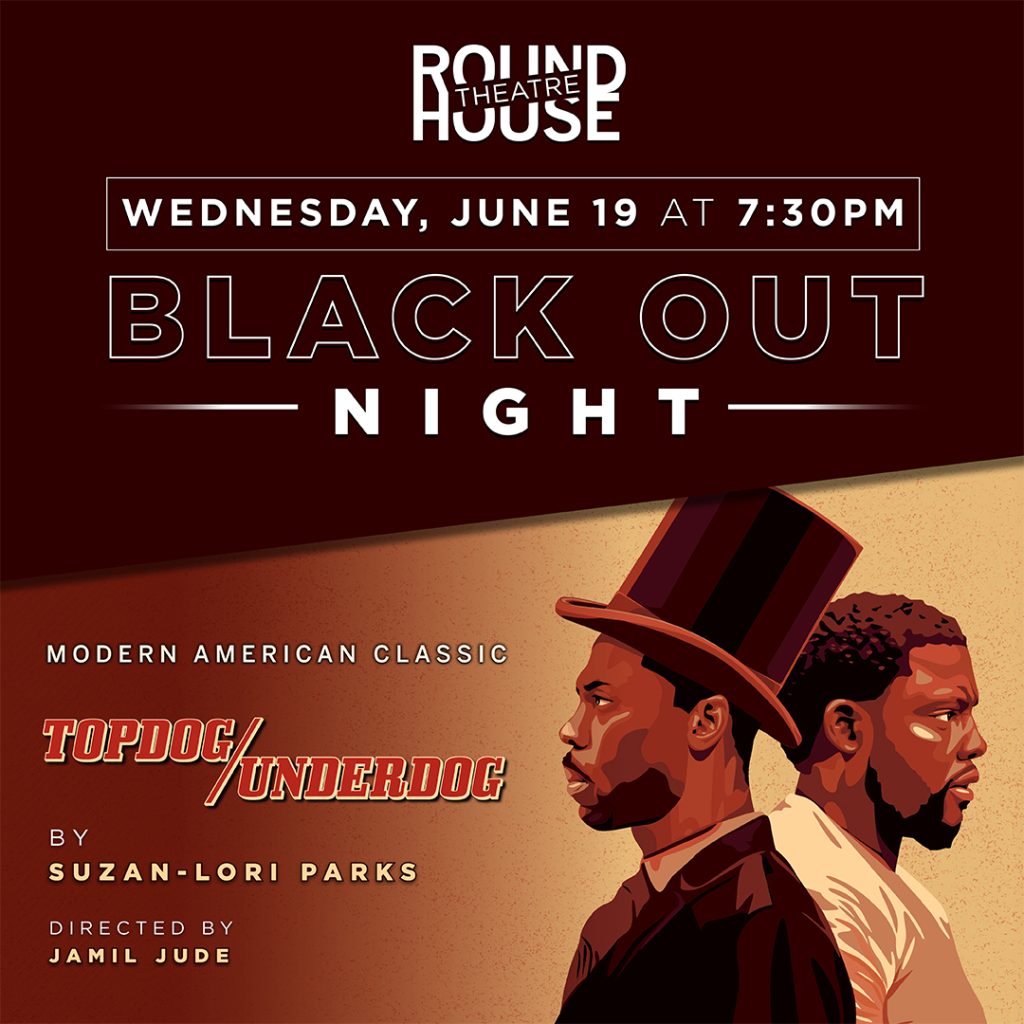

That’s how actor Ro Boddie describes a Black Out night, a single performance of a play set aside for an all-Black audience. Boddie has been onstage for a few, including Round House Theatre’s 2023 production of the August Wilson play Radio Golf. Now, he’s back at Round House with Topdog/Underdog, an acclaimed two-hander from Suzan–Lori Parks, which made her the first Black woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in Drama back in 2002. That show is getting a Black Out night, too—on Juneteenth, no less.

The story is set in the original period in which it was written by director Jamil Jude, but Topdog/Underdog could just as easily take place today. Two Black brothers named, ironically, Lincoln (Boddie) and Booth (Yao Dogbe) chart very different paths out of poverty: Lincoln by donning whiteface and a stovepipe hat to reenact his famous namesake’s assassination for paying customers, Booth by playing in the high-stakes world of three-card monte. Unfortunately, the two are trapped in a vicious cycle, haunted by their parents’ abandonment of them and the machinations of a racist, dog-eat-dog system.

It’s weighty material, but if Boddie’s past experience is anything to go by, playing it for an all-Black audience is still going to be special. “There’s something about having a play about a specific people and specific culture and having those people out there to witness it,” he says. “You get to hear what the playwright truly intended it to sound like, get to feel that vibrancy and [that energy]. It’s completely different.”

Black Out nights in their current state took off in 2019 when playwright Jeremy O. Harris helped fill the house of his controversial Broadway show Slave Play with an all-Black audience. As recently detailed in American Theatre magazine, the initiative followed similar efforts by playwright Dominique Morisseau, who lobbied for more diverse audiences during the 2017 Lincoln Center production of her play Pipeline. Today, Black Out nights, and other performances designated for marginalized groups who might identify with the action onstage, are one of the ways theaters are working to make their audiences more representative of the world around us.

One of the key proponents in the D.C.-area is Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, whose 2022 Black Out night for Jordan Cooper’s Ain’t No Mo also invoked the Black churchgoing experience. Kristen Jackson, Woolly’s associate artistic director and connectivity director, describes her experience as a Black audience member at these events as “transformative.”

“To be in a setting where there is a shared understanding, where specific jokes land differently based on said shared understanding and cultural references, to know that BIPOC characters are not being laughed at but laughed with—these are really important experiences to be able to have in a theater,” she says.

Freeing Black audiences and performers from “the white gaze” is a common theme among advocates for the practice. “Anyone who sees this play, or any play, has that empathetic ability to put themselves in the shoes of the artists or the actors,” says Dogbe of Topdog/Underdog. “But when it is a Black audience for a Black play, I absolutely think it takes it to another level because of the shorthand. I actually think there’s less work you have to do.”

“Less work” means being able to trust the audience to pick up the nuances in a performance rather than being swayed by stereotypes. This is especially apropos for Topdog/Underdog, argues Round House associate director and production dramaturg Naysan Mojgani. “There are these narratives [about Black people] that are part of our culture that are embedded within the play and that can be uncomfortable,” he says, pointing to myths about negligent parenting and so-called “Black on Black” violence. “To be able to [experience the play] without the white gaze involved is freeing, is liberating, and it makes for a far less stressful experience.”

Mojgani goes on to say that the “long history of both de jure and de facto barriers and hostility to marginalized communities” in mainstream theater makes programming such as Black Out performances a welcome development. Anderson Wells, managing director at Constellation Theatre Company, concurs, arguing that restrained, Western modes of engaging theatrical performance were impressed upon Black people during slavery and continue to inhibit them in mixed spaces. Wells points to Constellation’s Black Out night for its 2022 production of the Lynn Ahrens and Stephen Flaherty musical Once On This Island as an example of what goes well when those oppressive norms are broken down.

“It provided an opportunity for audience, cast, and crew to step away from this kind of Westernized version of what theater has to be,” they say. “By isolating the audience and the actors to specifically Black people, we were able to create a space that let go of those ideals and allowed the audience to feel more like they were part of the action.”

According to Wells, the Once On This Island Black Out night created a safe space for a vocal exchange between the audience and performers.

While the value of Black Out nights and other such programs are obvious to many artists and leaders, the logistics, philosophies, and expectations for them differ. Many theater programmers draw a distinction between Black Out nights and “affinity” or “community” nights. For Round House, Woolly Mammoth, and Constellation, Black Out nights are all about filling seats with an all-Black-identifying audience. Affinity or community nights—which might center South Asian, Nigerian, or LGBTQIA audience members, to name a few previous local examples—are open to anyone but framed as a celebration of the community in question.

Constellation, which will host a Black Out night for its production of Aleshea Harris’ Is God Is on June 21, offers a range of affinity programming throughout the season, which Wells sees as part of a larger process of audience diversification across race, age, income, gender, and sexual identity. However, Wells insists that, because of the unique historical and contemporary pressures on Black audiences, the distinction between how a Black Out night and an affinity night operate remains pertinent: “Our belief at this point is that operating another affinity night [solely for other marginalized communities] would not provide the same sort of freedom from oppression that Black Out night does.”

This is a position many of Wells’ local counterparts share, though it is applied in various ways. Folger Theatre, for example, recently programmed its first Black Out night for its production of Mary Zimmerman’s Metamorphoses, which, in this case, was a preshow event that was open to anyone but geared especially toward Black audience members. The company has since followed up with a “Soulful Sunday” for Black organizations and an LGBTQIA affinity night.

For Karen Ann Daniels, the artistic director of Folger Theatre, the choice to open with a smaller Black Out event was partly about meeting the audience rather than the format. “I come at this from more of a community perspective and not from an established model,” she says. “This is about us getting to know the community we want to serve. We pilot things, we try things, we learn and we build upon that learning—that’s my approach. It has less to do with what other people are doing and more to do with what our communities are interested in and how they respond.”

Though largely supported, or at least accepted, by non-Black patrons, some theaters have faced occasional resistance, ostensibly on matters of principle. After the Topdog/Underdog Black Out night was announced in May, Round House received an email from a self-professed progressive who expressed concern that such an event was a backward step that would only reinforce racial divisions. Though Mojgani acknowledges the critique was made in good faith, he maintains these programs are a small measure in pursuit of a bigger goal.

“If the fear is that by segregating in this way, we’re contributing to a culture of racial division, well, we already live in a culture of racial division!” Mojgani continues “In this instance, we’re saying yes, we may be dividing by race in this moment, but it is in the service of integrating the larger experience.”

Daniels also contests concerns about these events reinforcing racial divisions: “To those people, I would say there’s no real evidence [that this practice is exclusionary]. In fact, in my experience working with lots of different kinds of communities and different cultural backgrounds, people look at these things as an acknowledgment. It’s like us saying, ‘We know, we’ve missed you. We ignored you!’”

Beyond the philosophical considerations, there are also practical complexities. To reach their targeted audiences, theaters sometimes partner with community organizations that provide their constituents with special access codes to tickets for the event; in other cases, as with Round House’s Topdog/Underdog, theaters advertise the event publicly and frame it accordingly. And while every theater leader City Paper spoke with say no one is turned away from a Black Out night, they will make the intention of the evening clear to those who don’t fit the brief but show up anyway. This can make for some awkward conversations, particularly if the Black Out night was announced after tickets went on sale, as has been the case with Woolly Mammoth’s events in the past—something they’re striving to ensure doesn’t happen in the future.

Pricing is another matter. Constellation made its initial Black Out night free, which had an adverse effect on attendance, says Wells. They have since moved to discounted tickets. Round House also offers discounts, though Mojgani worries it can potentially send a problematic message about Black audiences needing cheaper tickets, and possibly create a steep ramp up to regular ticket pricing, should audiences want to return to another show.

Theaters also have to reckon with how discounted tickets affect their bottom line. For Woolly, that means baking Black Out nights and affinity programming into the budget. “The majority of our tickets for our Black Out nights, specifically, have been pay-what-you-will tickets,” says Jackson. “We’ve actually flexed our financial goals around our artistic goal of cultivating and creating this space.”

When it comes to gauging these programs’ long-term efficacy in diversifying audiences, expectations vary. “Whether [people] come or not, to me, is not actually that important,” says Daniels. “It’s more about what we’re signaling, which is to say, this is a space where you are welcome.”

For others, demonstrating the need for such programs by filling seats is still the objective. Some theaters eventually hope to track ticket sales to determine if audiences who come to a Black Out or affinity night return for another show.

Despite the many positive testimonials and general support, there is skepticism that Black Out and affinity nights are simply social justice trends. “I don’t think we’re going to keep Black Out nights,” admits Topdog director Jude, who is also the artistic director of Atlanta’s Kenny Leon’s True Colors Theatre Company, which is devoted to putting on Black work. “I think that some administrators are going to say it’s hard to put together, someone’s going to point to metrics and say it really doesn’t happen, or that ‘because we only program two Black shows in an eight-show season, it’s not really going to be worth it.’”

However, Jude acknowledges that comparatively small companies like True Colors can’t support Black artists alone; there will always be a need to facilitate safe spaces elsewhere. “You should always try to fling open the doors to bring as many people in and make them feel as comfortable inside your theater as possible,” says Jude. “If you’re only offering up one night—fine—they’ll be like, ‘hey, at least I know this is the night I’m supposed to go.’”

Jude and others are also quick to point out that while the Black Out label might be new, programming for all-Black audiences is not: Theaters have previously hosted “Divine Nine nights” to court Black Greek life, and as Jackson notes, Black audiences have long used salons and church gatherings in order to celebrate Black work on their own terms.

For her part, Daniels believes these initiatives will evolve as she and her colleagues continue to take down barriers. What matters is serving the audience truthfully. “The important piece of the work is to focus on where you are and who you’re serving,” she says. “These things, all these museums,” she says of the Folger’s recently renovated spaces, “we’re saving this stuff for you! That’s ultimately what it is. We’re creating these stories for you.”

Round House Theatre’s Black Out Night for Suzan-Lori Parks’s Topdog/Underdog starts at 7:30 p.m. on June 19. The play runs through June 30 at the Bethesda theater. roundhousetheatre.org.

Constellation Theatre Company’s Black Out Night for Aleshea Harris’ Is God Is starts at 8 p.m. on June 21. The play runs through July 14 at Source Theatre. constellationtheatre.org.