Two days after hourly employees at the private, billionaire-owned Glenstone art museum voted to unionize, a member of the leadership team felt compelled to share his thoughts. In particular, Director of Regional Partnerships Paul Tukey had some choice words for the employees “who don’t feel lucky to work here.”

“Glenstone is great because of the vision and generosity of two people,” Tukey wrote in an email addressed to his boss, co-founder and director Emily Wei Rales, as well as the rest of the museum’s staff. “I believe we’re the lucky ones, who work for people who paid us during Covid, who create paid positions that would be filled by volunteers virtually anywhere else, who have taken the high road at every turn in the past week despite truly sad untruths being shared publicly.

“I hope we get through this and all learn from it,” Tukey added. “And I hope, in the end, that the people who don’t feel lucky to work here no longer do.”

Tukey’s note, sent June 9, echoes the sentiments and tactics from the museum’s leadership, including billionaire co-founders Emily and Mitchell Rales, who worked against employees’ efforts to unionize. After this story originally published, Tukey responded to City Paper’s request for comment saying his email represents his personal point of view after 14 years of working at Glenstone. He also said that, despite the “director” in his title, he does not consider himself a member of the leadership team.

Glenstone management declined to voluntarily recognize the union in early May, prompting an election on June 6 and 7 with the National Labor Relations Board, a federal agency dedicated to protecting employees’ rights to unionize and addressing unfair working conditions. In the weeks leading up to the vote, the museum’s leadership launched what one employee calls an “anti-union campaign.”

In May, Wei Rales sent an all-staff email with a set of union “FAQs,” aimed at stirring up opposition to the organizing efforts. One answer suggests that hourly wages at Glenstone have increased at a higher rate than the average annual union-negotiated wage. Another answer highlights the fact that members would be required to pay dues, and yet another suggests that individual employees would lose flexibility in asking for raises, time off, remote work, “and lots of other things everyone takes for granted now.”

“Also keep in mind that the reason unions strike is to bring economic pressure on the employer to agree to the union’s demands,” one answer says. “But of course Glenstone is free to all visitors, and the museum is not dependent on any revenue that comes from being open. In the event of a strike, the real losers would be the public.”

Elizabeth Shaw, a grounds and visitor services liaison at the museum, tells City Paper via email that the museum’s leadership also hosted a Q&A session where some associates who were not included in the bargaining unit “delivered prepared statements about negative past experiences with unions and expressed fears about how a union would negatively impact what makes Glenstone special.”

Emily and Mitchell Rales also FedExed letters to their employees’ homes, encouraging them to vote against unionization, according to the Washington Post. “It is our sincere hope that you give due consideration to voting NO and keeping the Teamsters out of this special place we’ve built together,” the letter, signed by both Emily and Mitchell, says.

“I think we live in such a deeply capitalistic society that it’s like, ‘Oh, it’s not affecting money, that means it’s not affecting anything at all,’” Shaw says. “But our goal isn’t profit, we’re a nonprofit, so we’re just thinking … what would happen if all of these people didn’t come to work? What wouldn’t get done? The grass wouldn’t get mowed, the windows wouldn’t get cleaned. There’s all of this labor, and striking brings attention to that labor.”

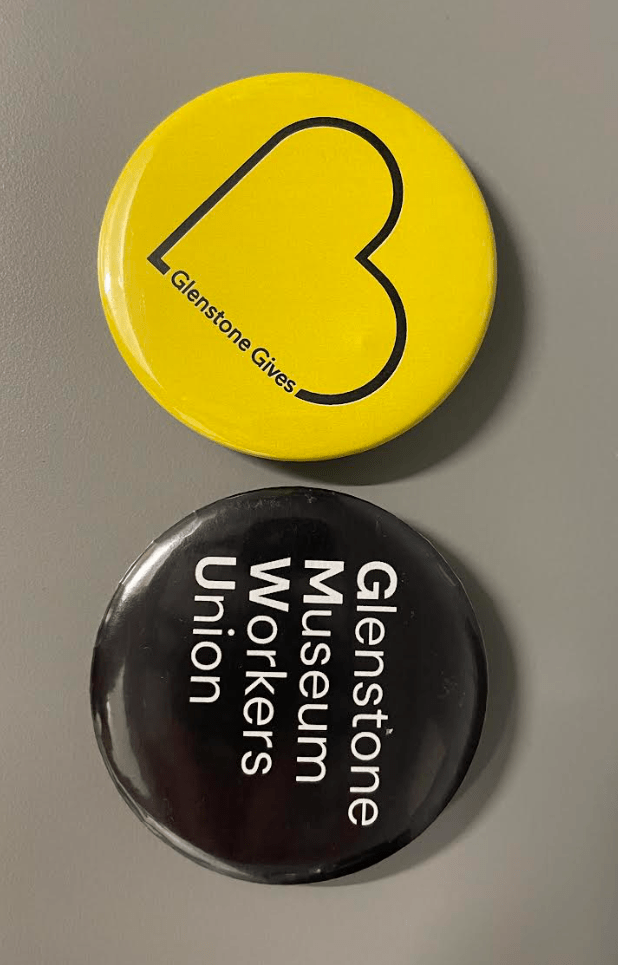

The FAQs, along with yellow pins featuring a heart and the slogan “Glenstone Gives,” were widely distributed throughout the sprawling campus, Shaw says.

“This response points to a concerted anti-union campaign on behalf of Glenstone leadership,” she adds.

Employees at Glenstone officially voted 53 to 27 to form a union last Friday. (Seven votes were not counted because Glenstone management argued the employees were not eligible to participate in the election.) The vote took place about a month after Shaw delivered a letter of intent to unionize to Wei Rales. The letter requested a living wage, health insurance, safe working conditions, transparency, and effective communication.

Glenstone Museum Workers Union, or GMWU, will be affiliated with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and now represents 88 of the museum’s workers.

After the election, the museum released a statement saying, “From the very beginning of this process, we have said we respect the right of our associates to decide whether to join a union. The majority have now elected to be represented by Teamsters Local 639, with one out of three voting against being represented by the union. Guided by our core values, we will negotiate in good faith. We recommit ourselves to working in a spirit of direct and meaningful engagement with all our associates, union and non-union alike, to strengthen the entire Glenstone community.”

All of the current and former employees interviewed by City Paper say there were significant upsides to working at Glenstone. They talked about rewarding collaborations between departments and opportunities to help shape young minds while working with student visitors. There’s also the built-in perk of working on a beautiful campus filled with priceless art. Still, some current or former employees would not speak on the record and many expressed general discontent, especially when it comes to communication with management, employee benefits, and staff safety.

Shaw says that a Glenstone employee handbook required employees to provide a doctor’s note in some circumstances if they called in sick, which could pose a challenge for part-time workers who do not receive health insurance from the museum and might not be able to afford a visit to the doctor.

Employees tell City Paper that in the winter, they were not provided with thick coats as part of their uniforms. And in summer, the museum’s heat policy says that outdoor installations should stay open and staffed unless the temperature hits 105 degrees.

Some employees, however, opposed the union efforts.

Lead housekeeper, Glenda Ruiz, who has worked at the museum for six years, says she did not receive information from members of the bargaining unit about the unionization push until late in the process.

“Nobody [told] me nothing about that situation,” says Ruiz. “It is not only me, we have 10 people in my department and a lot of people know nothing about that.”

Fredy Sanchez, who works in the museum’s engineering department, says he also lacked information about unionization efforts and opposed the formation of a union. “I don’t know what their problems are 100 percent,” Sanchez says. “Rumors and stuff is they don’t get treated the way they want to get treated.”

***

After breaking off from their father’s real estate development company, Mitchell Rales and his brother Stephen Rales gained notoriety in the 1980s for staging hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of takeovers of companies using mostly borrowed money. A 1985 Forbes profile titled “Raiders in Short Pants” described the pair as “clever youngsters” who “are reapplying their real estate background to the world of manufacturing assets.”

“They look at a machine the way they look at a building: not as something that produces tires or a place to live, but as a source of cash flow to dangle before their bankers,” the article says. They were billionaires by 1999.

Mitchell refocused the investments of his flagship company Danaher toward life sciences and other STEM-focused businesses in 2016. On a recent podcast appearance, Mitchell said the company “went through this incredible journey of COVID that turbocharged our business.” He is currently worth around $5 billion, according to Forbes.

He became heavily involved in the art world around the time he connected with Emily in 2005. In 2006, the Glenstone Museum Foundation was registered as a nonprofit. But before opening his own museum, Mitchell made millions of dollars worth of donations to a number of arts institutions.

When the museum itself initially opened to visitors (by appointment only and under the constant gaze of a team of guards), one blogger described the Glenstone as “inhospitable and brilliant,” and a “magical, incredible and sinister place.” The museum has since become more approachable. Today, it’s free and open to the public four days per week. Glenstone has received heaps of praise from big shots in the art world. Last year, Evan Beard, executive vice president of art investment firm Masterworks, called the Raleses “a pillar of the Washington art landscape … the top of the totem pole, collector-wise.”

In 2019, the couple dropped $11.7 million on Lee Krasner’s painting, “The Eye Is the First Circle,” smashing the artist’s previous auction record. In 2022, the Glenstone Foundation had $4.4 billion in net assets, including the couple’s recent donation to the museum of $1.9 billion. At those sums, it’s logical for hourly employees to wonder why their demands for benefits such as health care received resistance.

John Russo, a visiting research professor at Georgetown University focused on labor, has an idea.

“He’s gonna lose power and decision-making,” Russo says. “It’s going to be more jointly made. … These are people with great power, and they don’t want their power diluted.”

In the week after employees announced their intent to unionize, the museum filed a statement of position with the NLRB, which kicked off discussions between the museum’s leadership—Senior Director of Collections Nora Cafritz and Senior Director of Operations and Planning Martin Lotz, represented by attorneys from the firm Proskauer Rose—and a lawyer for the Teamsters Local 639.

Proskauer Rose has represented various New York City museums including the Museum of Modern Art, the Tenement Museum, and the New Museum, all of which now have unionized staff—a growing trend at museums across the country. Recently formed museum staff unions include those at Seattle’s Frye Art Museum, the Guggenheim, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In 2019, a viral Google spreadsheet allowed workers in the arts to post their salaries in order to compare with those of museum officials. In many cases, the differences were stark.

“[Glenstone is] part of a growing trend,” says Kathy Newman, an associate professor of English at Carnegie Mellon University and the associate editor for arts and labor for the journal Labor. “I think this generation is saying, ‘If I’m not going to be able to take care of myself, I’m not interested in what you have to offer.’ And I really think it’s quite refreshing.”

Charlie Tirey was a contract worker at the Minneapolis Institute of Art before he was laid off by the museum during COVID lockdowns in 2020. In April of that year, Tirey started working with the Office and Professional Employees International Union to help fold contract workers into an existing union at MIA. He and his peers went through a process similar to what’s been happening at the Glenstone; MIA declined to voluntarily recognize their union membership, and the contract workers voted unanimously to unionize in April of 2022.

“I hope that [at] Glenstone, the staff that are unionizing are having conversations about who can step up to lead,” Tirey says. “I think always planning for the next step is the right way to go about it.”

Although Glenstone staff’s unionization effort has been successful, the work is far from over. Next the union must form a bargaining committee and draft a contract. Shaw says she wants all members of the new union—including those who voted against unionization efforts—to take a survey on what they feel is important. The goal of the survey is to gauge whether staff are in agreement over their demands.

For her part, Shaw feels lucky to work at Glenstone. “But I also care enough to want more for my colleagues,” she says. “I hope this win helps to foster a culture of mutual appreciation and respect that can serve as a foundation for a strong first contract.”

This story has been updated to include the number of collective bargaining members, Martin Lotz’s title, and with comment from Paul Tukey.