This is part of Two Bad, a series exploring Americans’ lackluster enthusiasm for the 2024 election and the problem of the third-party candidate.

The numbers tell a dismal story for the American electorate: A lot of Americans are dissatisfied with Joe Biden. An April AP-NORC poll found that about half of Democrats, at the time, didn’t want him to run again.

Donald Trump is faring better among his party’s voters, but not too significantly. And let’s not forget, he’s also facing some pretty substantial legal issues.

You might think, facing the exhausting prospect of a rehashed election, Americans would embrace an upstart challenger. And yet, with the possible exception of Ron DeSantis’ poll-lagging bid to beat Trump, all other candidates seem to be not very serious contenders. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is grabbing headlines with his dangerous and bizarre conspiracy theories and sad shirtless bench presses. Marianne Williamson is doing kooky things like comparing her bullying of campaign staffers with Abraham Lincoln commanding the Union troops. Larry Elder and Vivek Ramaswamy have captivated virtually zero attention. Everyone running against Biden and Trump in the primaries for the two major parties seems fringe. And there isn’t even any real enthusiasm building around a third-party candidate.

But it hasn’t always been this way. There have been serious third-party contenders in U.S. history—candidates who, as outsiders, shaped whole elections and whole political landscapes. We aren’t just talking about Ralph Nader and Ross Perot. The history of third-party candidates’ breaking or trying to break the grip of the Republican-Democratic binary starts in the 19th century. It’s worth revisiting some of those attempts to see what it took for those candidates to make a dent in the two-party firmament and how—or if—it could happen again.

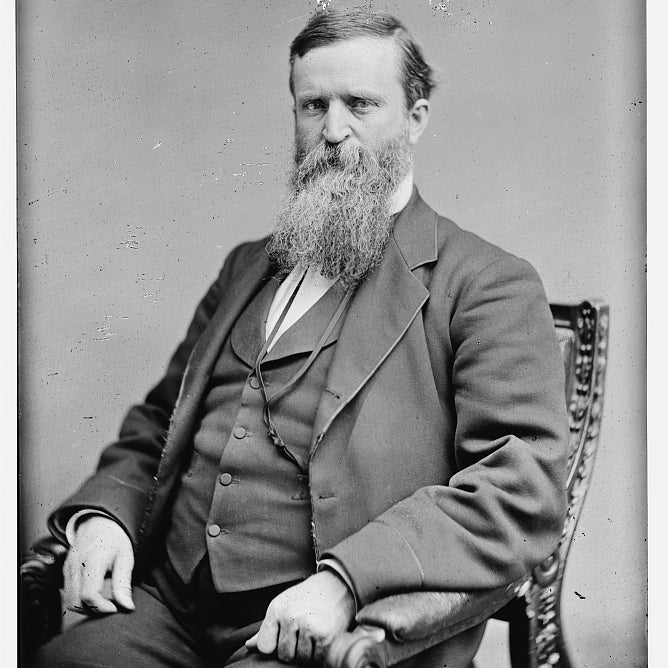

1892: James Weaver, People’s Party (Populists)

Who Was He?

Weaver began his political career as a Republican in Iowa, opposed, in the years just before the Civil War, to the spread of slavery. (This was a matter not of noble principle but of concern for the livelihood of white Midwestern farmers; he also promoted the white settlement of Native American land.) After the war, he failed to win public office and joined the nascent Greenback Party, which demanded a greater money supply, expanded business regulations, and espoused more progressive labor policies. With support from the Democrats, he was elected to Congress but gained virtually no traction as a Greenback candidate for president in 1880. Weaver pivoted again, helping form the People’s Party, also known as the Populists. The new group picked up the pieces of the Greenback Party and the Farmers’ Alliance movement and took on the cause of small farmers, who were at the mercy of large creditors and utterly reliant on the railroads for access to the market. The Populists sought federal regulations of those railroads, as well as an expansion of the currency, a graduated income tax, and collective bargaining—all in an effort to harness the frustrations of the working class when the conservative wings controlled both major parties’ platforms. Some from the Farmers’ Alliance originally thought they could work with the two extant parties but grew impatient when the Democrats rejected their platform.

Why Did He Join the Race?

The natural leader of the Populist Party was Farmers’ Alliance leader Leonidas L. Polk, who presided over the meeting that created the party. But Polk died suddenly in June 1892, leaving Weaver, the group’s second-most-prominent figure, as his natural successor. Weaver easily won the nomination. And although the Populists knew they were a long shot to win the race, they had reason to believe that a radical shake-up was possible: Weaver’s generation had seen the death of one major party (the Whigs) and the birth of another (the Republicans).

What Happened?

Weaver crossed the country in a national speaking tour in hopes of winning the support of farmers, but the party’s inclusion of Black farmers blocked any chance of success in the South, which went for the Democrat Grover Cleveland, who ultimately beat Benjamin Harrison to win the presidency. Still, Weaver won 22 electoral votes—all in the West and Midwest—and more than 1 million popular votes.

Who Did He Take Votes From?

Modern historians don’t consider Weaver a “spoiler candidate” since, in the 19th century, party membership was more fluid; single-issue parties pulled from factions within both the major parties, and they created alliances with other groups to promote their platforms. But some do note that his campaign forced the two other parties to address the demands of the working class. In the next election, Republicans nominated a conservative candidate favored by the banks, doubling down on the opposition. The Democrats, however, acceded to their left flank’s demands, putting forward the free-silver candidate William Jennings Bryan. In that race, Weaver would lend Populist support to Bryan, acknowledging the practical limitations of their situation and essentially killing off his party.

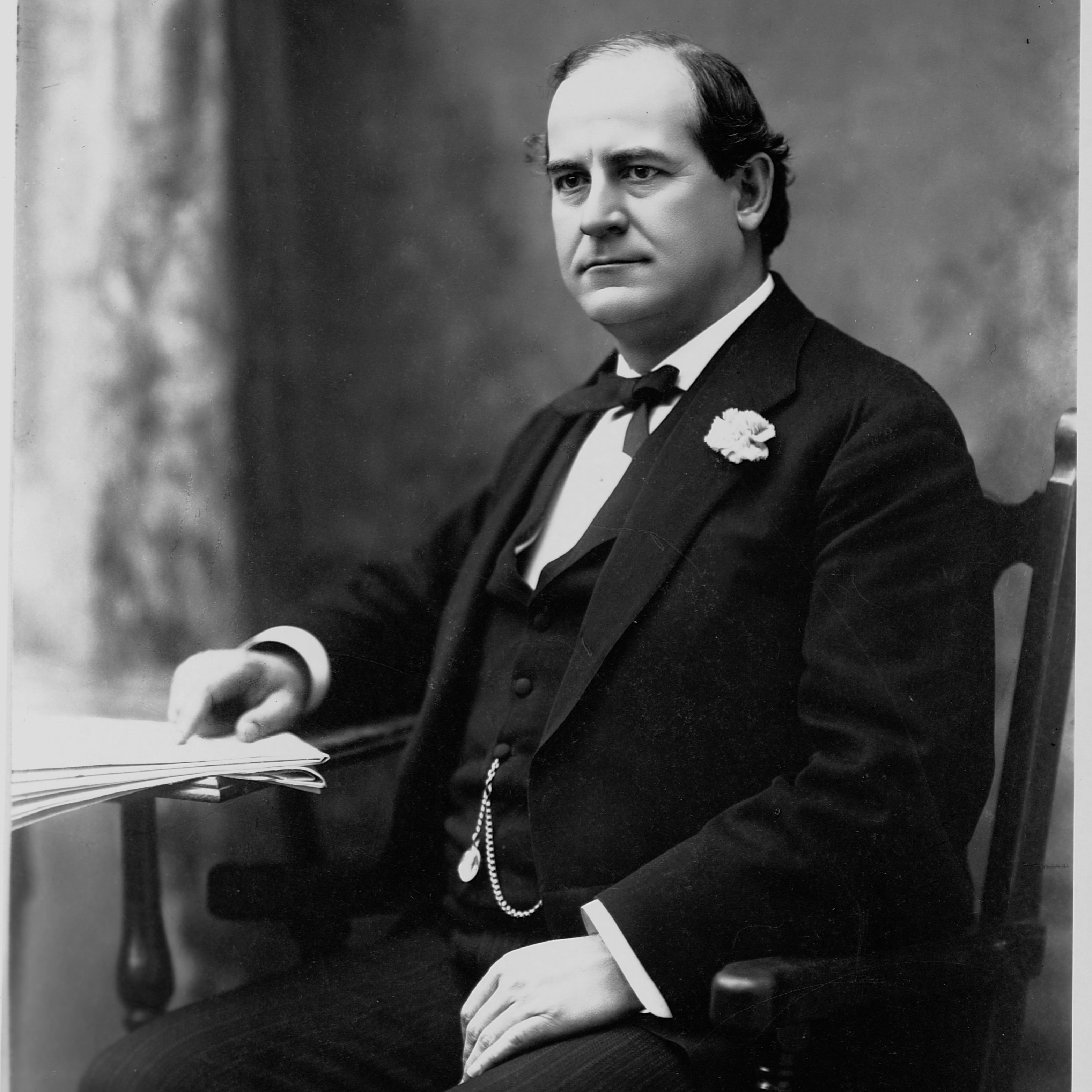

1896: William Jennings Bryan, Democratic Party and Populist Party

Who Was He?

Bryan was the candidate for two significant political parties in the 1896 presidential election: the Democrats and the Populists. At 36, he was and remains the youngest-ever major-party candidate for president. Bryan had been elected to Nebraska’s House of Representatives as a Democrat in 1893, and became the editor of the Omaha World-Herald a year later.

The “Great Commoner,” as he was known, was a man of many words: He earned his populist reputation as a renowned orator who relied on charm and delivery that often swayed voters more than his actual policies did. Bryan promised to legislate on behalf of farmers’ interests in the South and West, and as he backed their priorities, he drew on his strong religiosity to win their approval and trust.

Why Did He Join the Race?

Bryan’s commitment to diversifying the gold standard gave him his edge. After what he and many Democrats saw as a catastrophic Grover Cleveland term that yielded mass deflation in agricultural strongholds, the Democratic convention to nominate a candidate for the 1896 election became a stage to debate and solidify the party’s position on the money question. Bryan was the man with the answer: He delivered his pro-silver “Cross of Gold” speech at the convention, enchanting the gathering’s voters with a promise of prosperity. That speech—wrought with religiosity and a populist spirit that, in Bryan’s interpretation, resisted immigration (especially from China) and disregarded Black Americans—won him the Democratic nomination over Cleveland, the incumbent.

But in addition to that mainstay nomination, Bryan was also ticketed with a different vice presidential candidate for the Populist Party, which had formulated from a coalition of agitated farmers as a reaction to the rapid industrialization, mechanization, and financialization of the Gilded Age. By 1890, the party had won control of Kansas’ state Legislature, and the same state’s William Peffer became the Populists’ first senator. Then, in 1892, Weaver won 1 million votes in his third-party campaign for president. But this rise was accompanied by Southern Democrats’ attacks on the Populists. Bryan’s Democratic and reformist origins were divisive, as he represented a subsect of Populists that wanted to fuse with the Democrats rather than continue as a separate party. His 1896 race would prove both the party’s apex and its downfall.

What Happened?

Republican William McKinley beat Bryan in a landslide: 271 to 176 in the Electoral College, and by almost 1 million more ballots in the popular vote. McKinley’s backing by Northeast elites, wealthy farmers, and “skilled workers” is credited with winning him the election. The Great Commoner’s loss led to the Populist Party’s decline of power and prominence. His almost singularly white rural appeal rendered him unable to win any electoral vote–heavy Northeast states. Winning Texas with 15 was his crowning achievement; in comparison, McKinley won New York, Pennsylvania, and Illinois—all with between 24 and 36 allocated votes. Bryan ran for president in two subsequent elections as the Democratic Party’s nominee, losing each time, and eventually served two years as Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state. The Populist Party effectively split after Bryan’s 1896 loss into a socialist faction under Eugene V. Debs and a Democratic coalition, but its ethos and rhetoric had a long influence on presidential politics.

Who Did He Take Votes From?

Because he represented both the Democratic and Populist parties (despite having different vice presidential candidates in each), his votes collapsed into his Democratic total. But his Populist campaign won him 27 of his 176 Electoral College votes, a number of them in the South and Great Plains.

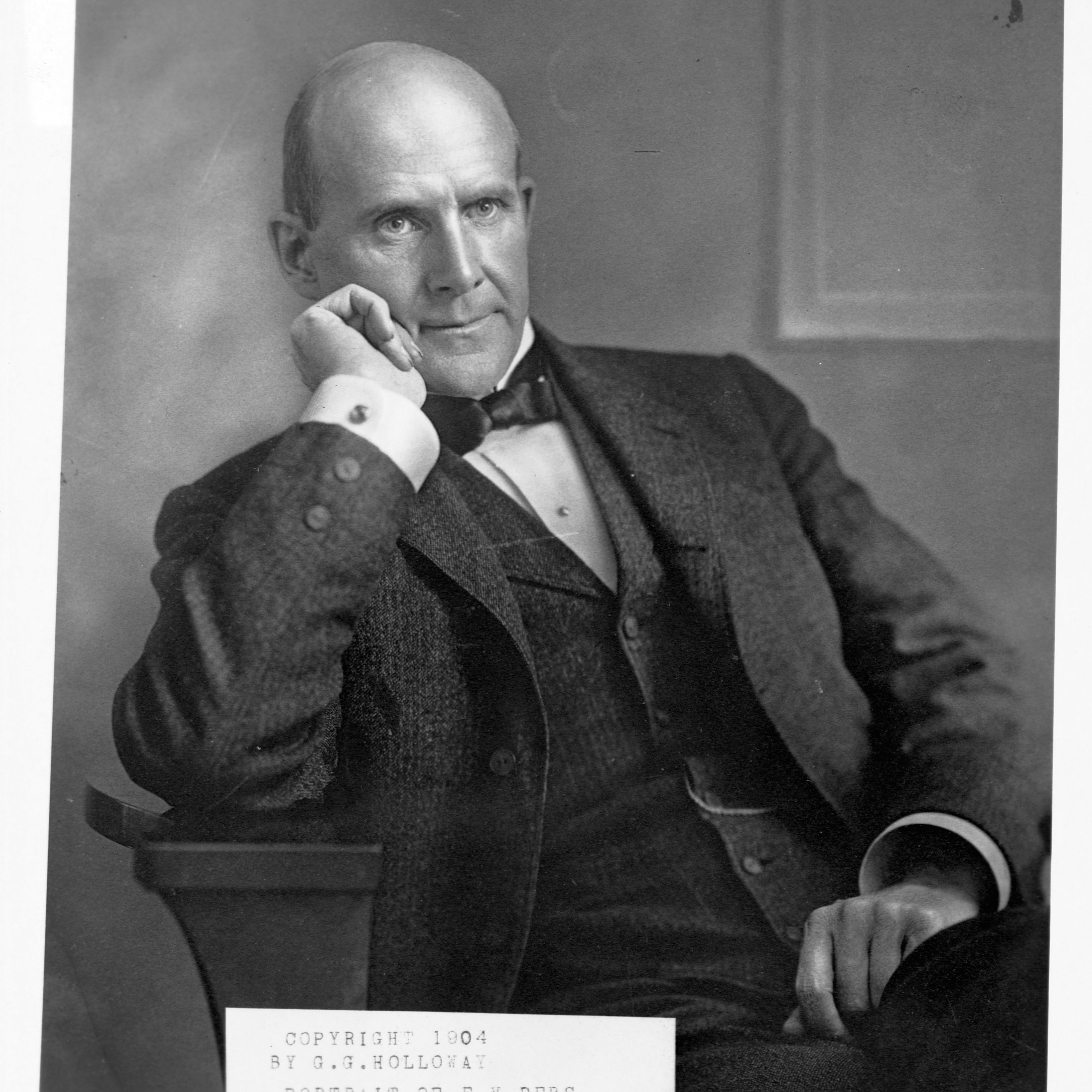

1912: Eugene V. Debs, American Socialist Party

Who Was He?

A five-time presidential candidate, Debs was a founding member of the International Workers of the World, a creator of countless unions, and a fierce labor activist whose work brought socialism to mainstream U.S. politics at the turn of the century. Born in 1855 in Terre Haute, Indiana, Debs dropped out of school at 14 and worked as a locomotive paint scraper, a fireman, an activist, and a labor organizer before entering politics. He was elected Terre Haute’s city clerk in 1879 before gaining a seat in the Indiana General Assembly as a Democrat in 1885. As the century came to a close, industry boomed and wealth became concentrated in the hands of very few men. Debs worked on railroads that produced and supplied foundations for much of the Gilded Age wealth, and he led the American Railway Union. He gained further notoriety after offering solidarity to workers during the 1894 Pullman Strike, which eventually led to his being jailed on conspiracy charges. While in jail, it is said, Debs underwent his “evolution from industrial cooperationist to revolutionary socialist” and began formulating a new Social Democratic Party. He ran for president independently in 1900, and with the Socialist Party of America in 1904 and 1908. In 1912, though, he received a significant amount of votes and influenced the outcome of an election for the first time.

Why Did He Join the Race?

Despite running several times before, Debs brought a unique and calculated working-class appeal to a field of reformists. The goal of his campaign—which brought him on speaking tours across the country—was to educate the nation’s workers about socialism, which he had extensively studied while in jail, and to translate Marxist ideas to the American experience. Gene, as his fans called him, offered a hopeful, anti-capitalist perspective that struck a chord with voters working in seemingly impossible, unchanging conditions.

What Happened?

Debs’ mission earned him almost 1 million popular votes, 6 percent of the popular total, but no Electoral College votes. He continued his activism and anti-capitalist pursuits even after his loss and was incarcerated for his outright criticism of the First World War and the draft. Debs ran his final presidential campaign from prison, and won nearly 1 million votes once more.

Who Did He Take Votes From?

Debs’ working-class voter base would have likely voted Democratic or not voted at all.

1912: Theodore Roosevelt, Progressive Party

Who Was He?

Born in New York City to a wealthy family, “Teddy” Roosevelt was first elected as a Republican to the New York Assembly in 1882. By the turn of the 20th century, he saw a rapid rise in political prominence. In five years, he rose to be assistant secretary of the Navy under President William McKinley, became a war hero with his “Rough Riders” in Cuba, was elected governor of New York, and got tapped to be McKinley’s vice president for his reelection campaign. After McKinley was assassinated in 1901, Roosevelt rose to the presidency to finish his predecessor’s term, and won a full term in 1904. As president, TR signed into law initiation bills for the Panama Canal and canal zone’s construction, created the National Park System (at the expense of Indigenous peoples), and imposed unprecedented regulations on big business.

Roosevelt is remembered for his Western expansionist mystique, his trust busting, and his growth of presidential power. For his time, he represented a progressive Republicanism that challenged his more conservative successor, President William Howard Taft, at the 1912 GOP convention. After Taft narrowly won the nomination, though, Roosevelt split with the Republican Party.

Why Did He Join the Race?

Roosevelt mounted his own convention under the new “Progressive Party.” Before leaving office in 1909, Roosevelt essentially chose Taft (who had been governor of the Philippines and secretary of war during his administration) to succeed him. Taft initially promised to continue Rooseveltian conservation, regulation, and expansion practices, but ultimately legislated further to the right, short of TR’s standards. Thus, after the contentious RNC, Roosevelt assembled the dissenting GOP members into his own faction.

What Happened?

Taft decided to not actively campaign, and Roosevelt garnered support with an anti-monopoly message he called “New Nationalism.” The Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson, countered Roosevelt with the idea of “New Freedom,” centering his message on tariff reductions, currency reforms, and direct senator elections. With Taft and Roosevelt dividing their portion of the electorate, Wilson won the Electoral College with a landslide 435 votes. Roosevelt came in second, with only 88, though he was just 2 million votes behind Wilson in the popular tally. Taft garnered a mere 8 electoral votes but was less than 1 million votes behind Roosevelt.

For Roosevelt, the loss set off a twilight in which he advocated for international U.S. military engagement and spoke in absolute favor of U.S. entry into World War I. The former assistant Navy secretary abhorred Wilson’s decision to remain neutral for some time. All four of Roosevelt’s sons fought in the war after the U.S. entered combat. He died shortly after the conflict, in 1919.

Who Did He Pull More Votes From?

Roosevelt’s ex-Republican affiliation and popularity from his presidency drew the party’s entire progressive faction away from Taft’s voting base. His choice to run ensured that the incumbent would not be reelected.

1924: Robert M. La Follete, Progressive Party

Who Was He?

La Follette, more lovingly referred to as “Fighting Bob,” was a prominent lawyer and lifelong politician from Wisconsin. Starting his career as a Republican, La Follette was in the U.S. House for six years, governor of his state for five, and a U.S. senator for 19 years until his death. Throughout his career, he worked against corporate control and political corruption, instituting direct elections in Wisconsin and earning his nickname for his oratory fire. He was devoted to working on in-state reforms with in-state experts, regulating the railroad industry while also growing business, funding for public education, and protecting the rights of workers and farmers, a philosophy of priorities that has been remembered as the “Wisconsin Idea.”

Why Did He Join the Race?

After La Follette supported Woodrow Wilson’s 1912 campaign, thereby inciting a feud with fellow progressive Republican Teddy Roosevelt, his political allegiances shifted: He was uninvolved with creating Roosevelt’s aforementioned Progressive Party. La Follette opposed Wilson’s military involvement in the Great War, believing that the investment would harm the American people and stifle his attempts at domestic reform. In 1922 La Follette was elected to serve another term in the Senate in a larger progressive congressional wave from Western states. La Follette turned this new bloc in Congress into an opposition group, and later into a political party for which he ran for president. His goal, he said, was to deconstruct private monopolies that had amassed too much power in a country that ought to be run by the people. This new, non-Roosevelt Progressive Party would represent the country’s laborers and farmers, not big business.

What Happened?

La Follette was up against the incumbent from his old party, Calvin Coolidge, and little-known conservative Democratic Sen. John W. Davis from West Virginia. Davis’ leanings drove some progressive Democrats to vote for La Follette, and ultimately, La Follette won one state in the Electoral College: his home state of Wisconsin. But he did come in second in many other states, outperforming Davis in those. Overall, though, La Follette totaled almost 5 million votes, about half of Davis’ tally and less than a third of Coolidge’s. Still, for a third-party candidate, winning 16.6 percent of the popular vote was monumental.

Which Candidate Did He Pull More Votes From?

La Follette, whose Progressive Party was allied with the Socialist and Farmer-Labor parties, took a large share of votes from each major political party. His ideals appealed to many on the left, but his vice presidential candidate was a former progressive Democrat, and he attracted others from that side of the aisle for whom Davis was too extreme.

1948: Strom Thurmond, Dixiecrat Party

Who Was He?

Strom Thurmond served in the Senate for 47 years, 5 months, and 8 days. Before that, he was the governor of South Carolina, was a city and county attorney, and fought in World War II. Through it all, he was a terrible racist, though he denied it, saying he opposed only excessive federal powers. Often touting his familial roots in the Confederacy and nostalgia for segregation-era policies, Thurmond in 1956 signed the Southern Manifesto against desegregation and holds the record for longest individual speech in the Senate: a 24-hour, 18-minute invective against the 1957 Civil Rights Act. Thurmond’s disdain for integration and the pursuit of civil rights, he claimed, came from his intense belief in states’ rights, which became the foundation upon which he built his 1948 “Dixiecrat” presidential campaign.

Why Did He Join the Race?

The 1948 Democratic National Convention proved to be a turning point for the character of the party. The convention sought to centralize civil rights in the party’s mission, but the Southern Democrats felt that this was an aberration—not just in their history of racism but also, they claimed, in expanding federal control to afford Black people any sort of equality with whites. With then-Gov. Thurmond as its leader, the group broke off and created the Dixiecrat Party for the upcoming election. Its members held their only convention in Birmingham, Alabama, in July and officially elected Thurmond as their standard-bearer. The Dixiecrats wanted to earn 127 electoral votes, making it impossible for either of the major parties to win the election, in which case the decision would belong to the House of Representatives. If the civil rights agenda—the most contentious issue of the election—was debated in the House, the Dixiecrats would have a chance at winning, they thought.

What Happened?

Thurmond did not earn 127 electoral votes. He won only 39, from four states in the Deep South, and just 2.4 percent of the popular vote. Democratic incumbent Harry Truman (who had assumed the presidency after FDR’s death) won with 303 electoral votes and a plurality of the popular vote (49.1 percent). Thurmond did not run for president again, but he continued his conservative “states’ rights” campaign in the GOP until he died in 2003, at age 100, just after leaving the Senate as its oldest-ever member.

Who Did He Take Votes From?

Thurmond voters came mostly from Truman’s base, but the sitting president triumphed by making up for it with the help of another third-party campaign: Many of Progressive Henry Wallace’s early supporters unexpectedly defected to voting for the president’s reelection, causing one of the biggest presidential upsets in history.

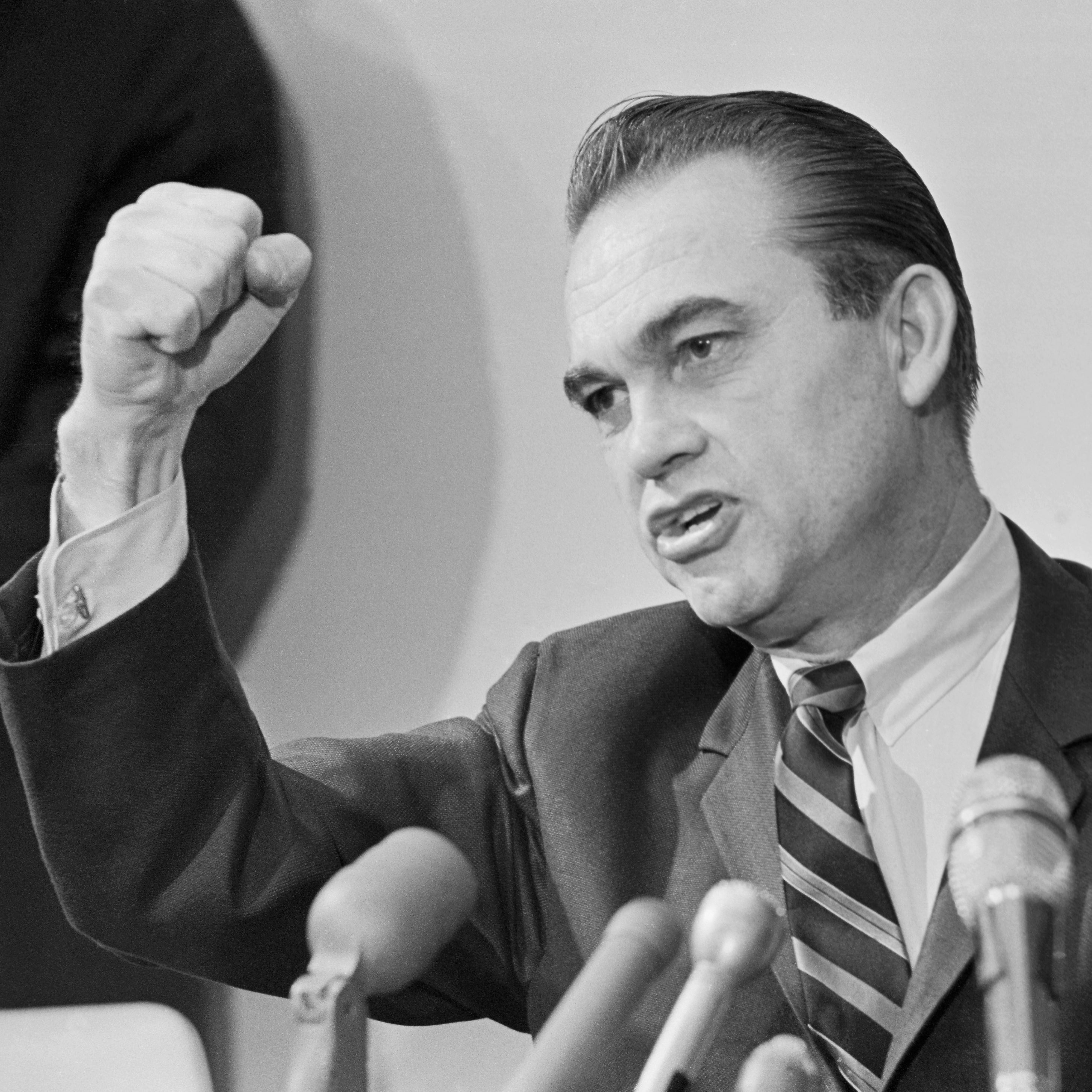

1968: George Wallace, American Independent Party

Who Was He?

Wallace is remembered for his prolific anti–civil rights campaign out of Alabama, saying proudly, in 1962, two years before the passage of the Civil Rights Act, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” He was a Democrat who fought in World War II, attended law school, and served as the assistant state’s attorney before being elected to the state Legislature in 1946. In ’62, he ran for governor for the first time and won his first of four nonconsecutive terms. (The state constitution forbade consecutive ones.) Wallace’s politics were rooted in a deeply racist breed of populism that claimed to help the poor but focused on enforcing racial divisions and disparities in income, welfare, and access to education.

Why Did He Join the Race?

The late 1960s marked an era of deindustrialization, divestment, and white flight from urban centers, resulting in a series of racialized riots. Many white Democrats, even some who viewed themselves as moderate or liberal on race issues, were entranced by Wallace’s outspokenness and “law and order” platform. In ’68, the Wallace campaign raised $9 million, and, like Thurmond before him, aimed to draw enough votes from Republican Richard Nixon and Democrat Hubert Humphrey that the election would move to the House. Wallace positioned himself in opposition to almost everything and everyone except the white working-class man: On the stump, he inveighed against hippies, the Supreme Court, and big government.

What Happened?

Wallace won an astounding 13.5 percent of the popular vote, five states in the South—Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas—and 46 electoral votes. Nixon narrowly won the popular vote, but he overwhelmingly won the Electoral College with 301 votes; Humphrey netted 191. Wallace attempted to win the presidential nomination on the Democratic ticket in 1972 and 1976, and never succeeded, but he won some states in his primaries along the way. After the 1968 race, he served two more terms as Alabama’s governor and continued his “states’ rights” tirades, failing to significantly deliver on improved conditions for even the small subset of white working people he claimed to support.

Who Did He Take More Votes From?

Wallace’s 10 million votes came from voters on both sides; they were significant, and almost substantial enough to achieve his goal of sending the election to the House of Representatives. Had he made further gains on Nixon in either North Carolina or Tennessee and had Humphrey won New Jersey or Ohio, the election would likely have been sent to the legislature.

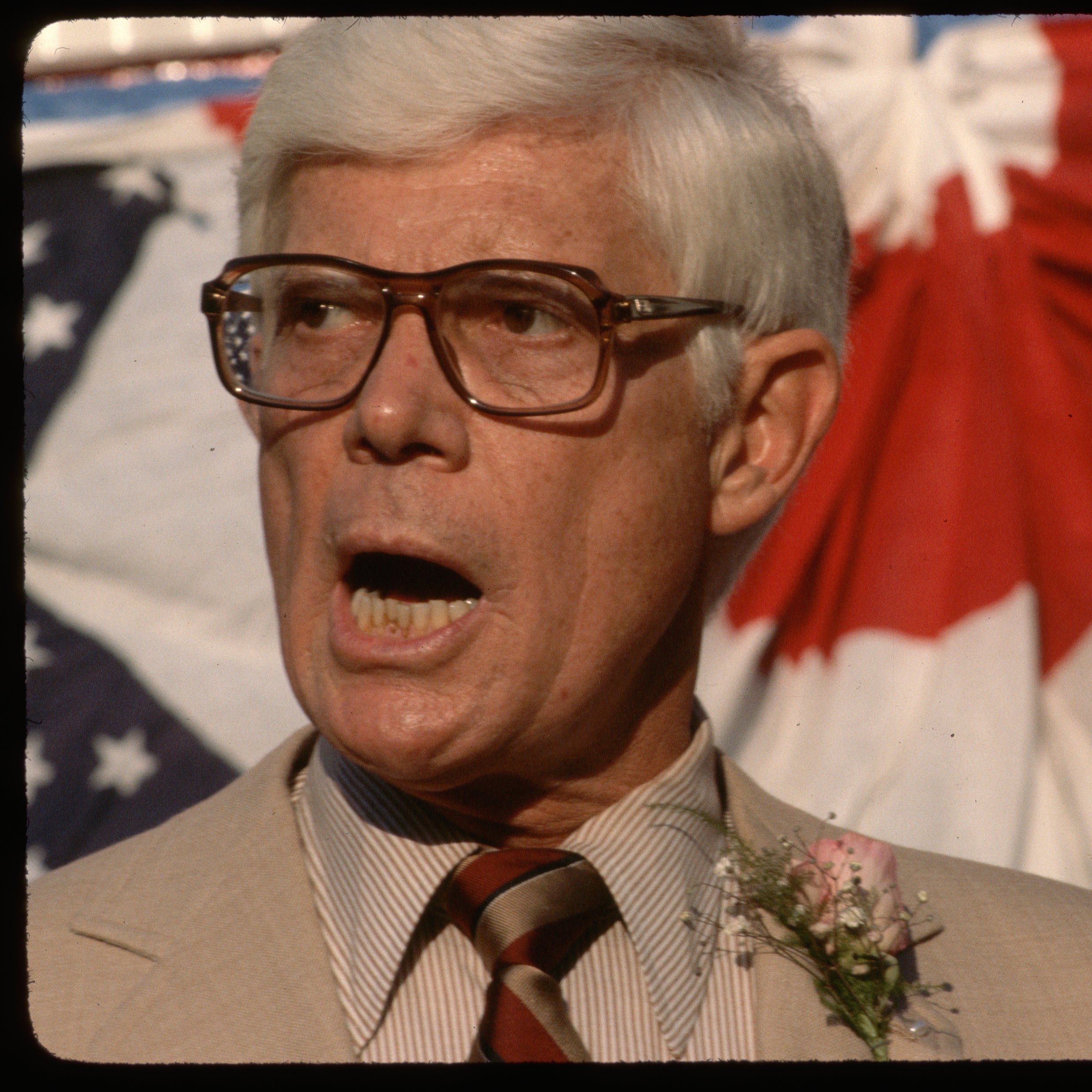

1980: John Anderson, Independent

Who Was He?

A 10-term congressman from Illinois, Anderson began his career as a standard conservative, opposed to Medicare and funding for public education. He thrice sponsored constitutional amendments that would have made the U.S. an officially Christian nation. But starting in the late ’60s, he shifted to the Republican Party’s left: He supported civil rights bills and firearm regulations and opposed the Vietnam War. His supporters saw him as honest and principled, his detractors as pompous and out of touch.

Why Did He Join the Race?

Like many third-party candidates, Anderson considered himself a reformer, frustrated by the failures of the system. He complained about special interest groups, partisan rancor, campaign finance issues, and politicians who prioritized electoral politics over the country’s actual needs. Convinced that conservative Democrats and more progressive Republicans would peel off to vote for him, he thought he stood a solid chance of winning over enough of a fractured electorate to cut through.

What Happened?

First, he ran as a Republican. He was surprisingly popular among newspaper columnists, liberal Hollywood stars, and college students, mainly because he came off as more of a principled scholar than a polished politician, citing statistics and stubbornly sticking to his unpopular stances as he demanded that his party act more charitably and honorably. (This included asking farmers to support a grain embargo after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.) But even though the race was crowded with right-wing conservatives, Anderson turned off many voters with his grandiloquence and ultimately failed to win over the conservative base. It didn’t help that he supported federally funded abortions for poor women and a 50-cent-per-gallon gasoline tax to deal with the oil crisis. After he lost six primaries, he withdrew to run instead as an independent.

At first, he was a real contender, polling as high as 26 percent in a three-way race with Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. He debated Reagan on TV. But as the race went along, Anderson was faced with the reality of running without a major party’s resources, and he slipped in the polls. His supporters largely defected to their second choices, and Anderson finished with less than 7 percent of the popular vote.

Who Did He Take Votes From?

It’s widely believed that he pulled more from Carter, the incumbent, than Reagan.

1992: Ross Perot, Independent

Who Was He?

A colorful character with an eventful life, Perot went from being a Navy officer to an IBM salesman before making his fortune as the founder of a data processing company, which he then sold to General Motors in 1984. Not content with simply being ultrarich, Perot turned himself into a folk hero by staging a famous attempt, in 1969, to deliver medicine and food to American POWs in Vietnam. A decade later, he attained greater fame after he financed a mission to rescue a couple of employees in Iran. (Authorities later questioned how much of a role Perot really played in the rescue.) With his short stature and comically folksy sayings, Perot charmed Americans who saw him as an anti-politician.

Why Did He Join the Race?

Setting aside the matter of his pathological need to succeed (he famously became an Eagle Scout only a year after joining the Boy Scouts when he was 12), Perot seems to have convinced himself that he could, as an outsider, cut through the bureaucratic and political nonsense of Washington.

What Happened?

Perot ran against incumbent George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton on the nostalgic idea of bringing back the imagined Norman Rockwell–esque simpler times, appealing to a good number of conservative voters who appreciated his hard line on immigration and drugs. Liberals liked him too, especially when it came to his moderate policies on abortion and gay rights. Voters across the spectrum admired his fixation on fiscal responsibility and commonsense aphorisms. As a candidate, Perot won nearly 20 million votes, or 19 percent overall. It was the strongest third-party showing since 1912, and many believe that his candidacy permanently changed how we discuss the federal deficit.

Today, however, a fashionable question to debate about Perot’s legacy is just how much he paved the way for the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Like Trump, Perot was a populist. He was a billionaire who had never previously held political office when he ran. He promised to disrupt the system, took his message directly to the voters without relying on normal media outlets, touted economic nationalism, had a weakness for conspiracy theories, mocked his opponents with childish taunts, and relied on his wealth for his celebrity. In 2000 Trump even considered running with the Reform Party—the party that Perot founded and ran under, more feebly, in 1996.

Who Did He Take Votes From?

The eternal debate over Perot’s 1992 run is whether Perot cost Bush the election. He directed most of his attacks on his Republican rival, causing some strategists to blame him for Bush’s loss. But modern experts have noted that the polling from the time shows that Perot’s support was politically broad. Most analysts agreed: Clinton was going to win the election, no matter what.

2000: Pat Buchanan, Reform Party

Who Was He?

A creature of Washington since birth, Buchanan made a name for himself in the Nixon administration and later the Reagan White House, as well as a columnist and as the host of CNN’s Crossfire. From the start, he was strident when it came to his deeply conservative beliefs and staked his place as the father of the culture wars—particularly when it came to gay rights, abortion, diversity, and immigration. He first ran for president in 1992, challenging George H.W. Bush for the Republican nomination, angry that the president had allowed increases in taxes and adamantly opposed to U.S. military intervention overseas. His extremism translated to some surprise success in New Hampshire, rattling the party. He tried again in 1996, this time giving another scare to the eventual nominee, Sen. Bob Dole.

Why Did He Join the Race?

To Buchanan, the Republicans were no longer conservative enough; they were too tolerant of the moderates in their midst, too similar to one another, and, like the Democrats, too entrenched in the establishment to truly address the country’s ills. Buchanan left the GOP in 1999, ready to take his paleoconservative, isolationist platform to the voters. The Reform Party, thanks to Perot’s campaign in 1996, gave him something to work with: more than $12 million in matching federal campaign funds and a guaranteed place on a number of states’ ballots. Roger Stone floated the idea of the Reform Party as Buchanan’s next political home, and Buchanan jumped at the idea.

What Happened?

Buchanan faced a momentary threat from Trump, who called off his campaign before it launched, citing the Reform Party’s extremism. Buchanan’s actual opponent, the transcendental meditation advocate John Hagelin, won over Perot’s more moderate followers and launched a flurry of lawsuits over claims of election fraud in the party’s primary. Hagelin would soon break from the Reform Party to host a separate convention on the same date as his old pals. (Perot would later state his opposition to Buchanan as the nominee.) Ultimately, Buchanan shook off his party’s internal turmoil and made a case for right-wing support, launching a series of racist and homophobic ads. (Buchanan had often been accused of antisemitism and was a little too closely connected to white supremacist activists for the broader electorate. He also had a baffling tendency to defend Nazi war criminals.) The candidate ran with his old isolationist and culture war causes and may have alienated some of his own supporters among the white nationalist right by nominating Ezola B. Foster, a conservative Black woman, as his running mate.

He won less than half of 1 percent of the national vote. The Reform Party was kneecapped by its own internal divisions and the exodus of moderates disturbed by the party’s numerous ties to white supremacists and other extremists. Buchanan would renege on his promise to stay in the Reform Party shortly after the election, returning to the GOP in 2004.

In the long run, Buchanan’s style of isolationist and nativist conservatism would emerge, after some dormancy in mainstream politics, in Trump. In the short run, though, Buchanan’s campaign was most influential in its simple presence on the ballot.

Who Did He Take Votes From?

Though Buchanan’s deliberate voters were archconservatives, some frustrated Al Gore supporters speculated that a confusing design in the Palm Beach, Florida, ballot—the infamous butterfly ballot—may have caused some voters to accidentally cast votes for Buchanan instead of Gore. Buchanan overperformed in Palm Beach compared to the town’s demographics, and may have cost Gore a win in the state—and, by extension, the election.

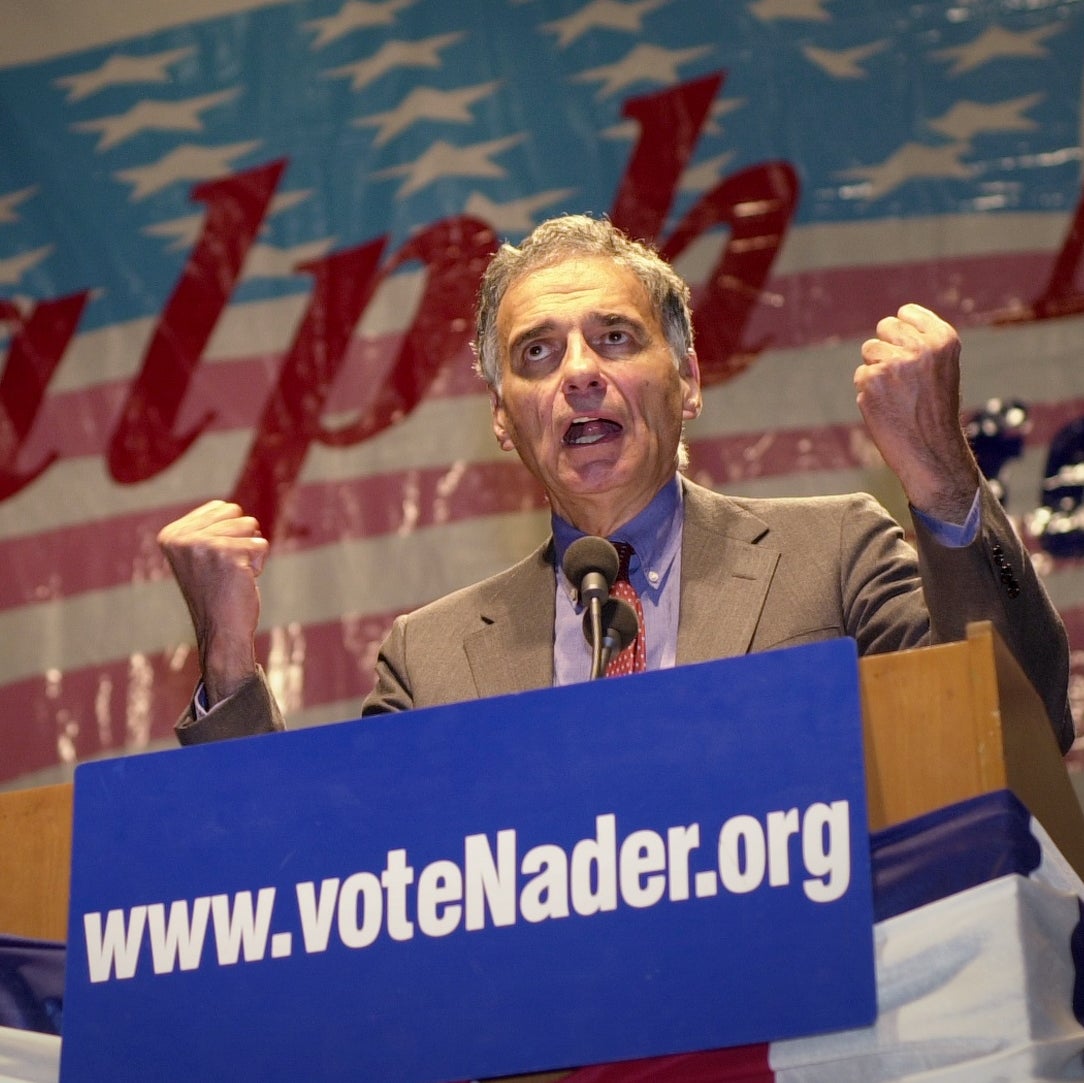

2000: Ralph Nader, Green Party

Who Was He?

A lawyer and writer who came to national prominence in the ’60s for an exposé on the automotive industry’s safety issues, Nader gained an enthusiastic following for his environmental, anti-nuclear, and consumer-protection activism. He founded several progressive watchdog groups and successfully helped campaign for a number of major federal protections for consumers, the environment, and political transparency. As a result, in the early ’70s progressive groups began floating his name as a presidential candidate. Nader rejected these overtures in 1972 and 1980, stood in as a write-in candidate in 1992, and represented various state Green parties in 1996.

Why Did He Join the Race?

Like other third-party candidates, Nader believed that Republicans and Democrats would not listen without a challenge. And like other third-party candidates, he saw little difference between the two major parties, which he believed were under the control of corporate interests. Just as Buchanan believed that Republicans weren’t conservative enough, Nader believed that Democrats weren’t nearly progressive enough.

What Happened?

Nader ran on a progressive platform: campaign finance reform, universal health care, affordable housing, free higher education, a living wage, marijuana legalization, criminal justice reform, labor-friendly policies, environmental protections, and higher taxes for corporations. Thousands flocked to see him in large rallies, and he became a hero of the left—that is, until it became clear he was a threat to Gore who refused to back down. Throughout his candidacy, Nader insisted that he had no responsibility to hinder George W. Bush—that both Republicans and Democrats were bad options, and that it could even be helpful for Democrats to learn lessons from and be energized by a Gore failure—and campaigned in key electoral states rather than sticking to more progressive-friendly ones, making it clear he didn’t want to win just the 5 percent of the popular vote that would secure the Green Party federal funding for the next election. Nader went on to receive 2.9 million votes, falling short of the 5 percent goal. But he did win 97,488 votes in Florida—a state Gore lost by only 537 votes. There’s a good reason many Democrats still bitterly blame Nader for Gore’s loss. If Buchanan harmed Gore’s chances, Nader, many believe, dealt the fatal blow.