When I first saw it, I assumed that it was a hoax. The photograph showed the girlish face of silent screen starlet Clara Bow, dressed in a coordinating blouse and hat, both emblazoned with a large, black, unmistakable swastika. Questions kept bubbling up. Was Old Hollywood icon Clara Bow a Nazi? Was the photo a fake, Bow the victim of Photoshop or some A.I.–generated fever dream? Or was there some other explanation for why this image existed?

It was easy to answer one of these questions: Yes, this photograph was real, and could be precisely dated, appearing on page 27 of the L.A. Times on April 13, 1928. “Ancient Cross Defies Jinx Day” proclaimed the headline, explaining that Bow was wearing the swastika symbol to ward off the bad luck of Friday the 13th. Not a hint, in the copy, of the associations between the swastika and antisemitic nationalist violence that was already taking place in Germany and Austria. Looking deeper, I found out that the swastika was a popular symbol in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, across Europe and particularly in the United States, where its use was widespread and fashionable, first infused with a sense of vaguely whimsical “exoticism,” and then perfect for the developing Art Deco aesthetic because of its angular, modernist lines.

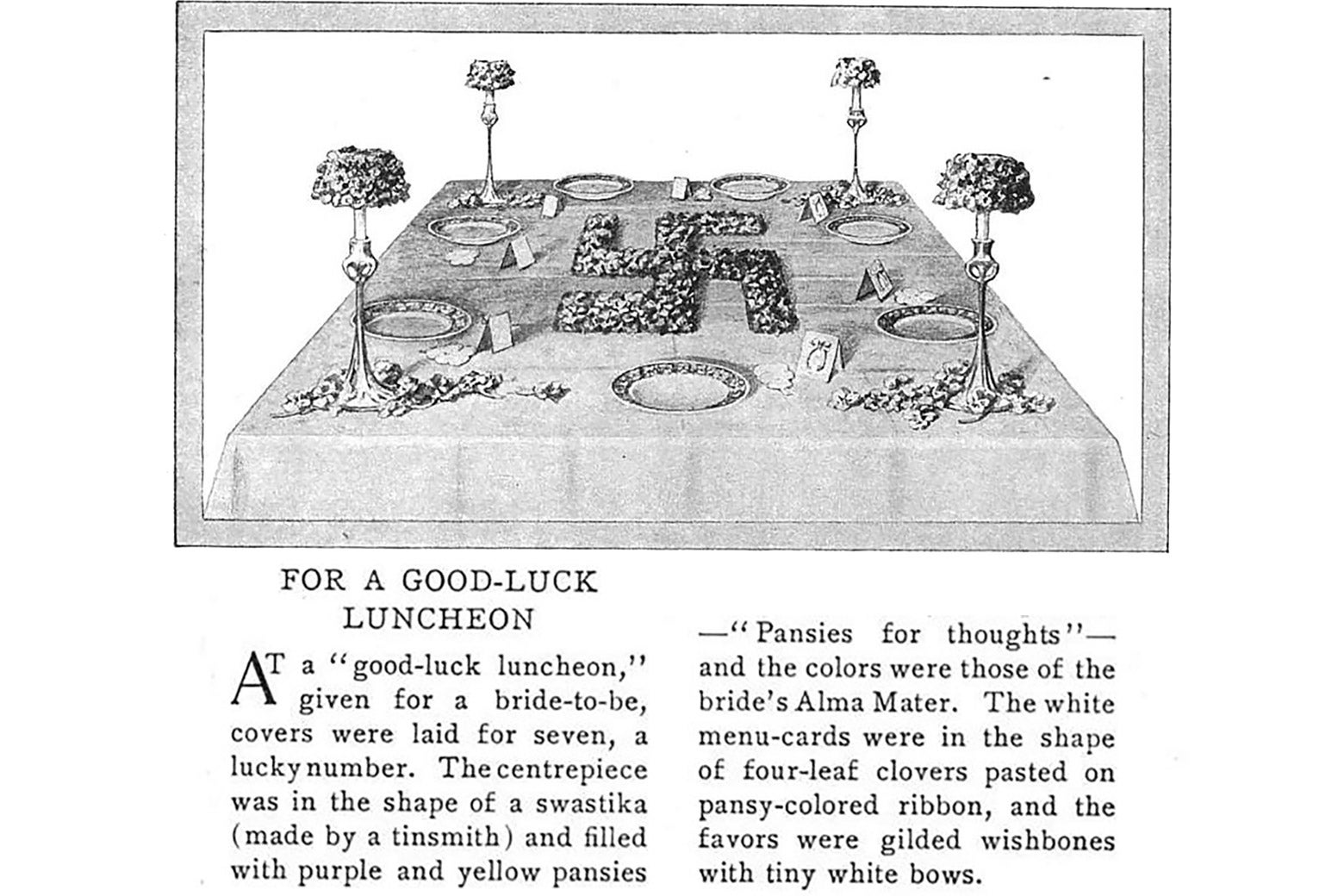

The symbol was, actually, ubiquitous. If you were a teenage girl in 1905 and you were looking to make a little extra money, you might sign up to sell subscriptions to the Ladies’ Home Journal, a popular women’s magazine. You would also be gratified to earn a special pin to show off your membership in what they called the “Girls’ Club”—a little gold swastika, featuring a diamond at the center, manufactured by Tiffany & Co. This would go nicely with your copy of the Girls’ Club newsletter, The Swastika. Perhaps you had a 1900 edition of a Rudyard Kipling publication like The Jungle Book, embossed with swastikas on the spine. Flipping through your Harper’s Bazaar or Good Housekeeping in the first decade of the 20th century, you might encounter advertisements or articles with illustrations of swastikas on jewelry, trim for towels, embellishments for pillows, table decorations for a “good-luck luncheon,” or crocheted coin purses. One ad for jewelry company Warren Mansfield included no fewer than five objects featuring swastikas, sometimes pairing the symbol with a four-leaf clover or teddy bear.

In the 1910s and 1920s, fashion designers too embraced the swastika. Actress Clara Bow was not the only one to wear swastika-themed outfits; fashion trade newspaper Women’s Wear Daily reported on sweaters, coats, and other ensembles featuring the symbol. The boxy fashions of the 1920s were especially suited to the use of the symbol, which was variably linked with Mexican, Chinese, and Peruvian origins.

These uses of the swastika in the United States were not without their own troubling associations. You do not need to go far to find the diversity of meanings and histories of the symbol. Examples of it appear in archaeological sites across Asia, the Americas, and Northern Europe. The swastika is a holy symbol in Buddhism, leading present-day priests such as Rev. Dr. T. Kenjitsu Nakagaki to argue for a linguistic and conceptual separation between the swastika and the hakenkreuz, or hooked cross, the term used for the swastika symbol in Germany during the Nazi era. Despite the swastika’s varied cultural sources, in the United States it was most often attributed to the Diné (Navajo) people, used as a sacred symbol in the ritual of sand painting. They, and other Native American communities, also began incorporating it into weaving, silver objects, and ceramics, many of which were sold to white consumers participating in what art historian Elizabeth Hutchinson has called “the Indian Craze,” a period starting in the 1890s in which objects made by Indigenous Americans were increasingly prized by white collectors. Much of the interest in Native American arts was centered on the preservation of cultures that appeared, to late-19th-century white Americans, on the verge of extinction—which was especially perverse, given the role of the United States government in that extinction.

When New York fashion designers used the swastika in their designs, they participated in what we might today call cultural appropriation. This was no accident; in the ’20s, the American fashion industry was trying to define itself outside the influence of Paris, the city that had been established as the center of fashionable inspiration since the 19th century. The New York fashion industry worked with museums such as the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art to understand what American design should look like. The swastika, given its association with Native American aesthetics and its easy adaptability, fit the bill exactly. For American designers of European descent, appropriating motifs with origins in Indigenous cultures from across North and South America—including the swastika—was a strategy to define themselves as independent from European design culture and to compete economically with European imports.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the swastika was gaining a reputation for other, more familiar, reasons. By the time Hitler joined the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (the precursor to the Nazi party) in 1919, they were already using the symbol. His innovation—according to his own writings—was to combine the swastika with the red, black, and white of the flag created in 1871 by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck to represent a unified Germany. In 1927 a journalist from Town & Country traveled to Austria to report on the conflict between nationalist antisemitic paramilitary forces and the Social Democratic Party. What came as a surprise to her was the response to a ring she was wearing, which featured a good-luck symbol fashionable back in the United States: a swastika. She wrote that a Viennese man begged her to take it off, explaining, “It is the sign of the ‘Hakenkreuzler’—of the Anti-Semites.”

After Hitler seized power in Germany in 1933, the swastika’s association with the Nazi Party became increasingly difficult to ignore. Another journalist—this time with the New Yorker—wrote about attending an anti-Hitler rally in New York City in 1933, where he, too, was stuck with an awkward accessory. He thought it prudent to conceal his swastika watch fob in his vest, realizing its uncomfortable implications. Accordingly, the number of mentions of swastika-themed objects in fashion and lifestyle magazines dropped off in the 1930s, while stories about Nazi Germany proliferated.

However, distaste for the swastika’s antisemitic connotations was not universal, and responses to the symbol revealed existing prejudices. One incident in 1936 made that clear. “Swastika Motif Receives Cold Reception,” read a small headline in Women’s Wear Daily in 1936. “Buttons crested with swastikas, shown by one couture house, stirred up some comment among an audience of New York buyers,” the editors wrote. “No sales of this particular model are reported.” Although no reason for this chilly response was given, it might be due to the fact that many important New York department stores were owned or founded by Jews, including B. Altman, Bloomingdale’s, Bergdorf Goodman, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Macy’s. Although the Women’s Wear Daily article left the designer of these buttons anonymous, Vogue also reported on a fashion show featuring swastika buttons, identifying the designer as Marcel Rochas, a well-known French couturier. Unlike Women’s Wear Daily, Vogue found the use of the swastika to be amusing, rather than disturbing.

This may be because Vogue did not see the swastika’s antisemitic connotations as inherently objectionable. Despite the patriotic turn that it would take when the United States entered the war, the approach of Vogue and other American lifestyle magazines to Hitler in the 1930s was neutral or even positive. An article in Town & Country in 1934 described the swastika-filled Nuurenberg rally as “a vastly friendly affair.” In 1936, a few months after reviewing the Rochas collection, Vogue featured photographs of the home decor of Hitler, Mussolini, and British Prime Minister Anthony Eden. A swastika cushion featured prominently in Hitler’s dining room. Rather than addressing Hitler’s policies, this image, and the magazine’s entire editorial approach, served to emphasize the humanity and domesticity of both the dictator and the swastika symbol.

As late as 1937, Good Housekeeping recommended creating a swastika out of cashews as a clever cake decoration, but the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 meant that the swastika finally became synonymous with the Nazi Party for an American audience. At that point, even those with arguably a better claim to the symbol rejected its troubling new meaning; in 1940, the Navajo, Papago, Hopi, and Apache all signed a proclamation renouncing the swastika symbol because it had been “desecrated recently by another nation of peoples.”

The consequences of interpreting these symbols correctly were not merely theoretical. When American pilot and Nazi sympathizer Laura Ingalls (a distant cousin of children’s author Laura Ingalls Wilder) was put on trial in 1942, her silver swastika bracelet was brought up as evidence of Ingalls’ Nazi leanings. Ingalls was a vocal supporter of the Third Reich and had been arrested by the FBI in 1941 for failure to register as an enemy agent. At trial, Ingalls argued that the bracelet “was not a Nazi swastika at all, but an Indian symbol of good luck.” Ingalls’ subsequent conviction did not rest on the evidence of her bracelet, but its role reveals that a politically neutral interpretation of the swastika had come to an end.

As for Clara Bow, there are no photographs showing her wearing a swastika after it came to be associated more with Nazism than good luck. She did visit Germany during her honeymoon in 1933 and Hitler—a fan—gave her an inscribed copy of Mein Kampf to remember him by.