The Supreme Court kicked the can down the road today on the case of Students for Fair Admissions’ case against Harvard University, with an invitation to the solicitor general to write a brief expressing the view of the United States. The invitation is a delay, but the case will be considered again. SFFA attempts to argue that the nation’s most famous college discriminates against Asian Americans in the admissions process, and even though it’s lost twice in court, it’s expected that this current court, packed with conservative justices, would rule in favor of the astroturf organization dedicated to killing affirmative action should it decide to hear the case.

SSFA’s leader, Ed Blum, has been trying for decades to eliminate affirmative action in college admissions. After he failed with Abigail Fisher’s suit against the University of Texas (that one argued Fisher had been discriminated against for being white but failed to provide compelling evidence), Blum started courting Asian American students who were rejected by Ivy League institutions. It is unclear how many he found, since not one student testified on SFFA’s behalf during the trial, but the organization’s legal strategy relied on statistical arguments to claim that Harvard’s admissions policies gave advantages to legacies, donors, athletes, and underrepresented minorities, which hurt Asian American applicants. In trying to claim an equivalence between providing unfair advantages to the already advantaged (legacies, donors, athletes) and taking race and racism into account during the admissions process, SFFA has cannily yoked its attack on race-conscious admissions to a critique of actually illegitimate advantages given to the white and wealthy.

But there’s a clear tell in this strategy that reveals SFFA does not really care about unearned advantages: It said nothing about graduating from a private high school.

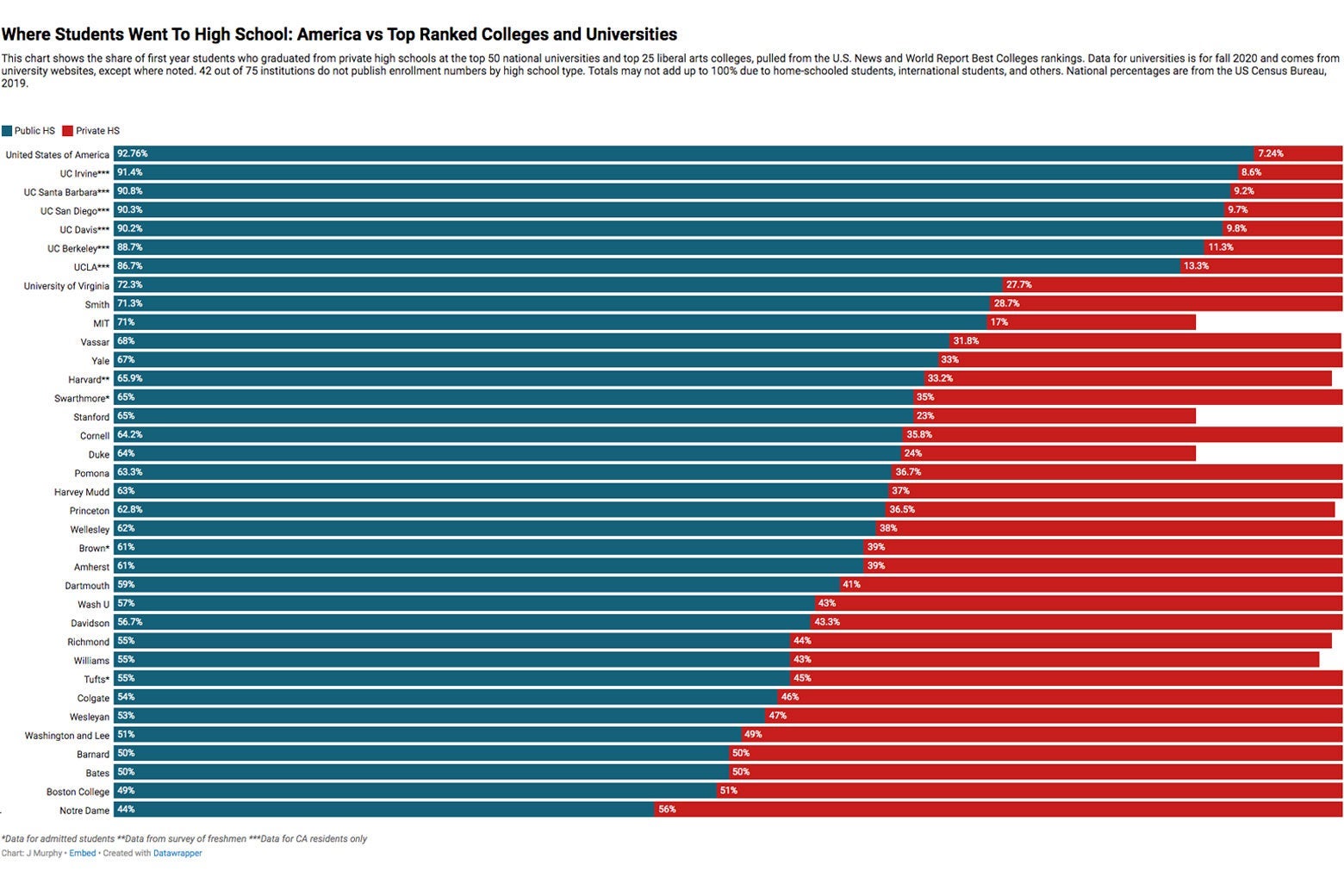

Graduating from private high school is a far larger advantage at many top ranked colleges than playing sports or being a legacy or even having a connection to a donor are. (Viewed a certain way, a private school is almost a more reliable income source for an elite college than a donor.) While 10 percent of students admitted to Harvard’s Class of 2018 were recruited athletes and 12 percent were legacies, almost 40 percent of the class went to a private school. If we really wanted to get rid of the most glaring case of bias at prestigious private universities, we would target private high school students.

Legacy, donor, and athletic preferences should be stripped out of college admissions too, but when it comes to tipping the scales away from fairness and equity, private schools outweigh everything else. Only 7 percent of high school students attended private high schools in the United States in 2019, according to Census Bureau data, but at many of the most selective colleges in the nation private school grads make up a third to half of freshman classes.

This is the real scandal in college admissions: Wealthy families pay for their children to attend high schools that receive preferential treatment in the admissions process at highly rejective colleges.

Defenders of private high schools’ overrepresentation at many highly ranked universities might claim the students have reaped the benefit of a more rigorous education in order to earn their spot. When you control for wealth, however, private school’s academic and social-emotional benefits are basically wiped out. Historically, students from the nation’s elite boarding schools “perform[ed] worse in the classroom [at Harvard] than other students over the entire 1924-1990 period” but went on to make more money than their peers by taking advantage of the connections they made in groups like final clubs, which largely exclude anyone who is not wealthy or white.

St. Grottlesex students and their peers at old nondenominational private schools might be a little less white and little less wealthy than they were a century ago, but have no doubt: These schools still do not look like America. This year’s graduating class of public high school students is the first projected to be majority-nonwhite, but almost 70 percent of private school students are white. That’s a product, in part, of a long history of white people pulling their children out of public schools after desegregation, and private schools continuing to make an outsize contribution to school segregation in the United States.

Most independent schools do provide some financial aid, but it often goes to a small share of students. At Marlborough, an independent school in Los Angeles where the cost of attendance is about $45,000, only 20 percent of families receive financial aid, and almost half of those who do still make more than $200,000 per year. About 6 percent of all the school’s students come from families making less than $100,000, even though almost two-thirds of American households make less than that. Some independent schools enroll a number of low-income students on scholarship, and these “privileged poor,” to use Anthony Jack’s term, account for half the low-income students at some highly selective universities, further evidence of the advantage granted to these schools in the admissions process.

Private high schools can cost as much as $70,000 per year. For those prices, students get not only single-digit student-to-teacher ratios, teachers with Ph.D.s, better sports facilities than those at many colleges, and art museums, but also college counselors who work with a fraction of the number of students public school counselors work with. At Horace Mann, in the Bronx, 180 seniors are served by eight college counselors. Fewer than 2 miles away, 12 guidance counselors work with 750 seniors at Bronx Science. Both high schools are full of very talented students, but only one of them pays its director of college counseling $350,000 per year.

That salary is an index of just how much emphasis the parents who pay for independent schools place on getting their kids into certain universities, which may be why the median salary for a college counselor at independent schools is $94,000 but the median salary for a teacher is $60,000, according to the National Association of Independent Schools. Many independent school counselors started in college admissions, often at highly selective colleges; one of the newest members of this rank was a dean of admissions at an Ivy League university just last fall. These high schools are paying not just for experts who know the rules of the game; they are paying for experts who know the referees. It’s a cozy world, where private school counselors meet up with admissions officers at small invitation-only annual meetings, like the Fitzwilliam Conference held in the woods of New Hampshire every May for three days, including a six-hour block for “golf, hiking, antiquing.” And then there’s the annual Clambake Institute, where private school counselors and admissions officers get together every summer at St. George’s School just outside Newport, Rhode Island—the perfect setting for cementing and perpetuating the special bond between rich high schools, rich students, and rich universities.

That special bond is cashed in through one of the least-well-known rituals of college admissions: the counselor call. It’s a decades-old tradition, in which school counselors and admissions officers review a list of students who have applied to a college, and counselors get a chance to make a case for their students. Swarthmore College put an end to the practice this past year after it discovered that more than 90 percent of their requests for counselor calls came from private high schools. This spring, USC began telling counselors requesting a call that any conversation would be informational, and asked counselors to “refrain from advocating for candidates.”

But simply attending certain high schools can provide enough of an advantage that no advocacy is needed. Harvard’s dean of admissions said as much under oath in 2018 during the SFFA trial: “[Sometimes] we take somebody … lower in the class … and we’ve got some other very attractive people at the upper end of the class. Sometimes you can make an argument to take them both because they’re both terrific.” The dean continued, “It’s also a very good message to that school that you may be trying to develop that you’re looking for all kinds of different people.”

In other words, someone thought that a good way for Harvard to defend itself against charges that it unfairly advantaged underrepresented minorities was to say, no, no, don’t worry, the unfair advantage goes to overrepresented wealthy students. The word develop gives away the game. Any head of admissions knows that he needs to build a reliable pipeline of customers from certain institutions. As Harvard’s dean testified, “We’re trying to create relationships with schools. … We’re trying to create 100-year relationships with them.”

Even as it feels counter to the endeavor of competitive admissions based on merit, it’s perfectly logical for colleges and private high schools to pursue cozy relationships. To quote Willie Sutton, that’s where the money is. A full-paying student at an Ivy League school is worth well more than a quarter-million dollars in revenue over four years, plus future donations. Some schools will send five or six students a year, which adds up to a million-plus in revenue, year over year for ideally a century or more, apparently. In return, the high schools gain a level of access that lets them charge more than what many Americans make per year.

To be fair, superselective universities also cultivate these relationships with organizations like Questbridge and some public school counselors to create a pipeline for high-achieving, low-income students, but the numbers suggest there’s a lot more pipe being laid on the Upper East Side of Manhattan than in the South Bronx or rural New York.

There is little point in criticizing any of the individuals involved in this corrupt relationship between private schools and highly selective colleges. The parents who send their kids to independent schools and the counselors and teachers working in them are, in my experience, conscientious and caring individuals keenly aware of their students’ privilege and their own, and many of them work hard to increase equity and diversity at their school and in college admissions. Some of them ran into opposition this past year, as a few white parents bristled at schools’ efforts to introduce diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in the wake of the anti-racist protests last summer as well as a string of affecting social media campaigns where Black students revealed the racism they routinely faced at school. If we are going to have an aristocracy, I guess it’s better to have a woke one. But wouldn’t it be better to have no aristocracy at all?

Short of eliminating private schools, we cannot eliminate the advantage families purchase by enrolling their children in them. We might, however, reduce some of that advantage by doing four things.

First, all universities should end counselor calls.

Second, universities should be required to report annually what type of high schools their first-time students attended, disaggregated by race. More than half of the top 75 institutions in the U.S. News & World Report rankings do not publish this information, suggesting they either do not think the overrepresentation of private high school students matters or that they want to keep that fact out of sight. I’m not sure which is worse.

Third, universities should stop asking school counselors for letters of recommendation. How can a counselor responsible for 200 seniors possibly write each one a letter as effectively as one with only 30 students can?

Fourth, admissions offices should redact the name of the school during the admissions process and stop assigning applications by region, as most highly selective colleges do. Context is essential for admissions officers to consider applicants’ merits rather than their accomplishments. A file could still contain relevant information about a high school, such as the number of students on free lunch programs, or its student-to-counselor ratio. Going school-blind would not erase context, but it would hide the brand names.

Highly selective colleges might not be ready to break their hundred-year relationships with private high schools. But they could certainly become less toxic for everyone else.