In early summer of 1978 my agent asked me if I would be interested in ghost writing a book for Jerry Rubin about his small penis. Rubin, the former anti-war protestor and activist, had signed a deal with Harcourt Brace Jovanovich for $35,000 to pen a self-help book for men with small endowments and premature ejaculation issues. If I were interested in collaborating with him, half of the advance would be mine.

It was a curious choice for a topic. Why would one of the most notorious dissenters of 20th century American politics choose to expose himself, so to speak?

Rubin had an impressive resume as a political activist and annoying pot-smoking hippie. He mobilized the 1967 March on Washington, which rallied 100,000 people to protest the war in Vietnam. He co-founded the countercultural Yippies—the Youth International Party—with fellow war protestor Abbie Hoffman. When the House Committee on Un-American Activities investigated him for being an anarchist, he blew bubbles at his hearing. He played the role of court jester by stomping on judicial robes at the infamous Chicago Seven trial in 1969, in which he and his six co-defendants were found guilty of inciting to riot at the 1968 Democratic convention. Rubin spent his 31/2-month prison sentence writing a revolutionary manifesto called, Do It!—about getting off the fence and bringing about change, the manuscript of which was smuggled out of jail by his lawyer.

It was also Rubin who piqued the FBI’s interest in John Lennon and Yoko Ono by convincing them to perform at a benefit concert to free John Sinclair, who had been arrested for selling two joints, at which John and Yoko were joined onstage by Black Panther leader Bobby Seale.

But it seemed that Rubin had long ago squeezed whatever life there was out of being an anti-war protestor. Over the past several years he had indulged in what he told The New York Times was a “smorgasbord course in New Consciousness,” including personality car washes like Esalen and EST, primal scream therapy, yoga, acupuncture and drinking so much carrot juice that his leg turned orange.

Having to think about Rubin’s small penis over the next few months sounded like a rather dreary way to spend the summer, but I was intrigued and needed the money. I said yes. |

In 1976, he wrote a best seller called Growing Up at Thirty-Seven about his experiments with inner change. The proposed book about Rubin’s small endowment was a continuing attempt to reinvent himself as a self-help expert. This evolution was spurred in part by his recent marriage to Mimi Leonard, the daughter of George Leonard, a journalist and editor of Look Magazine, who was also an early supporter of the self-development workshop EST. Ms. Leonard, who attended the Hewitt School in Manhattan and graduated magna cum laude from Columbia, was having her coming out party in 1966 just about the time Rubin was organizing the March on Washington.

Having to think about Rubin’s small penis over the next few months sounded like a rather dreary way to spend the summer, but I was intrigued and needed the money. I said yes. There was no audition of any sort, and I don’t believe Rubin ever read anything I wrote. I think he was most impressed because I had written Alice Cooper’s biography with the man himself. I talked on the phone once with Rubin and told him he should call the book, “Penis Wars.” That appealed to him greatly and I was hired.

***

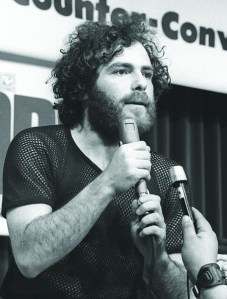

Rubin lived in a surprisingly bourgeois Upper East Side apartment building on Second Avenue, with a circular driveway and a fountain. I sat in his office a few days a week and took notes on his theories about sex. At 5-foot-6 and 130 pounds, he was intense, hyper, barefoot and always in need of a shave. I had never met anyone quite so demanding of my attention. I was exhausted when I got home after sessions with him.

He talked about envying other men who had normal-sized penises, “long enough to be held by hand,” he said. He told me how his anxiety about the size of his penis kept him from getting an erection, and how a woman he dated chased him out of a restaurant shouting, “Impotent! Impotent!” He railed against the fact that men were expected to produce erections on demand, and he had discussed his theory that women had “female blue balls” when they were horny.

He made all sorts of assertions about human sexuality that he seemed to be pulling out of thin air, like that cuddling was more intimate than sexual intercourse, or that a woman performing oral sex on a man was a subtle form of castration. He was running his own study, he said, as part of which he had distributed questionnaires to several thousand people, but only 100 or so had been returned.

We referred to Rubin’s penis innumerable times during those interviews, and one day I asked him if he wanted to give the reader a size reference. I mean, one man’s small might be another man’s O.K. He suggested I should see it. I told him it was unnecessary, but in another few seconds he had unzipped and there it was, the basis of my paycheck. I told him I had seen worse and asked him to cover up.

Rubin really didn’t have much of a book. There was no research, no thesis. He had no remedies for men with small penises. The best palliative he could suggest to his readers was that men shouldn’t put so much importance on penis size. “Love me, love my penis,” was his message. I realized that he didn’t really need a ghost writer, he needed a self-help writer to invent the entire book for him. I was the wrong guy and I had to tell him so.

But first, I had a suggestion for a topic he should address in the book. He might not have much of a penis, but he certainly had balls. Look at how he had the guts to stand up to authority, to mock the courts and the establishment. It took not only guts but rage. Perhaps part of his rage at the machine was about feeling he was less than a man? Was it possible he channeled his anger about his inadequacy into an amazing political force? Were his politics driven by ideological conviction, or because he was an angry guy with a small dick?

How dare I equate his insecurity about penis size with his political genius? Was I questioning his sincerity? Was I belittling his contribution to the counterculture movement? He was a hero. |

Naturally, he blew up at me. How dare I equate his insecurity about penis size with his political genius? Was I questioning his sincerity? Was I belittling his contribution to the counterculture movement? He was a hero. His political theater was not only entertaining, it succeeded in changing the way the courts and the government dealt with political dissent and second amendment rights. He had discredited authority and refused to be bullied into silence by the establishment, even from prison, where he wrote a book. He had deliberately polarized people and by doing so he saved thousands, maybe millions of lives. And what contribution to society had I made?

I was fired the next day. I was allowed to keep the payment already advanced to me and I never heard from Rubin again. The book was eventually released by Marek Pubishing in 1980, as The War Between the Sheets: What’s Happening with Men in Bed and What Men and Women Are Doing About It, co-authored with his wife. They were kind enough to thank me in the introduction for writing parts of the earliest personal drafts of the manuscript, and there is a subchapter entitled “Penis Wars,” the totality of my contribution. The book got terrible reviews. It was in part a compilation of other self-help books, all listed in the bibliography, peppered with Rubin’s irreverent observations and chapter headings like, “Three Cheers for the Tongue and the Finger” or “Learning from Lesbians.” The book was quickly pulped and forgotten.

In the 1980s, Rubin seemed to embrace all the values he had so effectively mocked. The guy who threw money onto the floor of the stock market to make fun of stockbrokers scurrying for the bills became a securities broker and a salesman at John Muir & Company, securing investments for energy efficient companies. He held networking salons at Studio 54, often attended by as many as 1,500 people, and held a series of Yippie vs. Yuppie debates with his old pal Abbie Hoffman. He became a father, too, of a son and daughter. In 1991, he and his family moved to Los Angeles where he became a successful independent marketer for a Dallas-based firm that sold a nutritional drink called Wow!, made with kelp, ginseng and bee pollen. Ironically, Bobby Seale became one of his salesmen.

I lost track of Jerry Rubin until 20 years ago. On November 28, 1994, Rubin tried to cross Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles against the light. Wilshire Boulevard is six lanes wide coming through Westwood, as wide as a highway, with cars whizzing by at high speeds. It would have been impossible to dodge cars and make it safely to the other side, but Rubin had been dodging trouble his whole life. That night his luck ran out; a car swerved to avoid hitting him, and the car right behind ran him over. He died a week later at UCLA Hospital.

When California State Senator Tom Hayden, who was Rubin’s Chicago Seven co-defendant, was told that Rubin died jaywalking, Mr. Hayden told The Los Angeles Times, “Up to the end, he was defying authority.”