In the awful summer weeks after the downfall of Roe, I picked up Susan Faludi’s Backlash. I wasn’t alone, either. Faludi’s classic work of media criticism had fresh appeal, well after its publication in 1991. So did her diagnosis. The second wave rose, and in the years after, reactionary politics gathered strength. Feminism’s right-wing detractors told a simple story: “that women’s equality is responsible for women’s unhappiness.” In 2022, when I read her, I felt that little had changed. Antifeminist backlash had been with us for so long that when Roe fell, it was obviously the casualty of a much longer war.

Roe had always seemed fragile to me, and so did mainstream feminism when I first encountered it in the mid-2000s. I am a daughter of Evangelical parents, and I knew how much money and manpower went to the war on abortion in particular. Feminism was at a comparative disadvantage, and it is still in a defensive crouch. Cultural dominance eludes it. Anti-feminist influencers proliferate on social media and their followings grow. “The last decade in American life was full of headlines that trumpeted feminism’s rising power, and, reliably, what greeted these headline moments was swift retrenchment,” Molly Fischer wrote for The New Yorker, in her own reconsideration of Backlash.

Today’s anti-feminists have much in common with the New Right. During the 1980s, when I was born, conservatives felt threatened by the potential loss of status and power. “They are not so much defending a prevailing order as resurrecting an outmoded or imagined one,” as Faludi put it. The New Right was revanchist in character. Men like Paul Weyrich, who co-founded the Heritage Foundation, steered it in an explicitly antifeminist direction. Adherents didn’t get everything they wanted, but they made important gains. In 1980, when Ronald Reagan was elected president, the GOP drafted a party platform that “opposed legal abortion and the Equal Rights Amendment.” (It was, as Faludi noted, the first time since 1940 that the party did not endorse the ERA.) Reagan not only rejected the amendment; he supported the “Human Life Amendment” that would have overturned Roe. As president, he pursued welfare cuts that pushed poor mothers deeper into poverty.

Resurrection for the New Right meant the demise of women’s liberation. Even the conservative women who supported their project would have to accept male supremacy in the end. That much was clear from a 1980 speech by Weyrich, quoted by Faludi. “We are different from previous generations of conservatives,” he boasted. “We are no longer working to preserve the status quo. We are radicals, working to overturn the present power structure of the country.”

The events of 2024 won’t determine the future of backlash, or that of feminism itself, but they will be an important marker. Trump has become the presumptive leader of a reactionary, deeply anti-feminist movement. A victory for him in this year’s election would be a victory for gender traditionalism. As Adam Serwer wrote in The Atlantic, traditional beliefs about gender are “inarguably a big part of the Republican policy agenda, which includes abortion bans and anti-LGBTQ legislation.” Trump is a natural fit for that party, and so are his grievance politics. In his own telling, he is an underdog beset by culturally dominant forces — the courts, the Marxists, the woke. A jury found him liable for the sexual assault of E. Jean Carroll. Dozens of other women have accused him of sexual harassment and abuse. He has said that when you are a star you can do anything to women, even grab them by the pussy. If Trump wins again, he and his movement allies plan to purge the government of “wokeness.” Though several women appear on his rumored vice-presidential shortlist, they wouldn’t be the first to launder the reputation of a powerful misogynist.

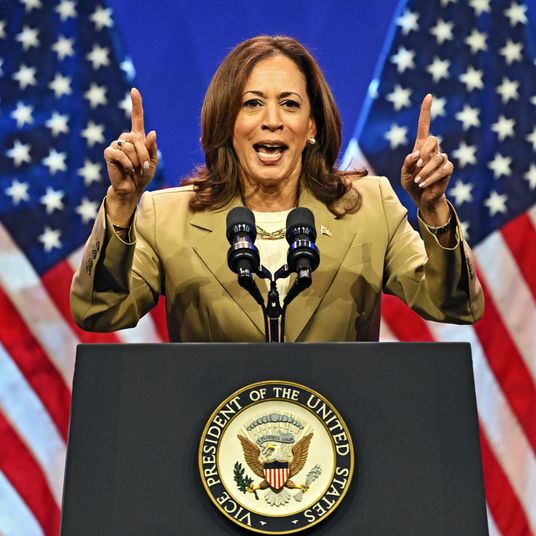

What can feminists do now? Vote, Democrats say, and they aren’t entirely wrong. Given Trump’s return and the end of Roe, the forthcoming election is partly a referendum on anti-feminist backlash. The conservative movement has moved on to the abortion pill, to civil rights for LGBTQ people, even to no-fault divorce. As feminists face backlash on one side, they find little to inspire them on the other. Joe Biden grossly mishandled the Anita Hill hearings and supported the Hyde Amendment, which bars federal funding for abortion, as recently as 2019. Biden later reversed his position on Hyde, and has said, too, that he would sign a bill codifying Roe — the minimum that women should expect from any Democratic candidate. His choice of Kamala Harris as running mate helped bind the Democratic coalition together and put a woman of color close to the presidency. Harris, though, has trouble of her own. The former prosecutor is unpopular in the polls, where her race and gender surely count against her. Should Biden and Harris triumph over Trump a second time, they could provide a slight buffer between women and the heirs of Weyrich, but that’s likely all.

Electoral politics has its limitations for feminism. Women do not vote as a monolithic group. Trump is an unrepentant racist, and he has historically performed better with white women than with Black or Hispanic women. The polls are tight this year, too. Yet a gender gap persists overall. An NBC News poll released earlier this month found that Biden is winning women by ten points while Trump leads him among men by 22 points. The gap appeared again in a Quinnipiac University poll from January, showing 58 percent of women preferred Biden and 53 percent of men preferred Trump. Backlash may hold the conservative coalition together, but it might not win a general election.

The right’s future conquests are not yet assured. Much still hinges on women themselves. To Republicans, they are both a prize to win and a threat to abhor, as the party struggles to win them over. To Democrats, they are members of a coalition that too many still take for granted. Women aren’t mere voters; they can be mature political actors, worth more than focus-group feminism. “In the past, women have proven that they can resist in a meaningful way, when they have had a clear agenda that is unsanitized and unapologetic, a mobilized mass that is forceful and public, and a conviction that is uncompromising and relentless,” Faludi wrote in her epilogue. That mobilized mass does not exist. The Women’s March is a memory, and so are the post-Roe rallies. But women’s anger has not dissipated either. In referendum after referendum, voters are embracing abortion rights. Women are challenging right-wing groups like Moms for Liberty in their communities. They are self-managing abortions, and helping others get care. They are providing mutual aid. There’s still hope for a better future.

Whether Democrats seize that hope is up to them. Abortion is a winning issue, but women need a comprehensive vision from the party. The Biden administration could make a more effective case for its economic gains, and the party will have to address the trouble spots that remain. Renters are in crisis, and while inflation is improving, groceries are still expensive. On immigration, there is often little daylight between Biden and his Republican foes. A doomed bipartisan border bill, championed by the White House, would have given the administration “emergency powers to refuse entry to migrants crossing the border or to quickly expel those who had already entered the U.S.,” Reuters reported. Biden must still decide if he champions all women or just a few.

Feminism won’t be won or lost at the ballot box. At its best, it is too subversive for any party to capture, and at its worst, it is too white, too wealthy, too consumed with pop culture and individual choice to make much of a difference at all. Yet I am committed to it because I have lived the alternative. I know, too, that the backlash isn’t going anywhere, but Faludi wrote that there is one thing it cannot take away. “Because, whatever new obstacles are mounted against the future march toward equality, whatever new myths invented, penalties levied, opportunities rescinded, or degradations imposed, no one can ever take from the American woman the justness of her cause,” she wrote. It seems, sometimes, that justness counts for little. The power structure of the country does not belong to us, and the radicals of the right are on the march. But the grassroots can still be ours, and so could the future. We cannot lose sight of our rightness, not this year, or whatever comes next.