This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

One afternoon in late July, J. B. Pritzker reclined in a conference room high above Chicago and considered the curious case of Ron DeSantis. Pritzker, the 58-year-old governor of Illinois, was in light-blue shirtsleeves and a neatly knotted bright-pink tie — “My Barbie tie,” he quipped to business leaders earlier, revealing he’d watched the movie with his wife and daughter. He was slightly bewildered by the Florida governor’s misfortunes in the GOP presidential primary, which had recently led DeSantis to lay off a huge chunk of his staff amid cratering poll numbers. “I had never really paid a lot of attention to his manner and his personality so much, only to his policies and his hype and the extremist positions,” Pritzker told me, speaking carefully as he settled into pundit mode. “But the point is that is not what’s killing him.”

Pritzker, who, with his dark hair and broad face, looks a little like Oliver Platt playing an ’80s businessman, started to speed up, as if the topic were more exciting than he wanted to let on. “You get the sense of somebody who doesn’t actually care about people. He’s just got a shtick that he puts on for the purposes of a campaign,” he said. Pritzker, who has spent plenty of time with presidential candidates and thought plenty about what it takes to run for president, concluded, “You have to believe what you believe to your core in order to make it through a process like that.” And, he said of DeSantis, “it appears to me that he doesn’t actually have a core.”

This take was worth considering not because of Pritzker’s own flirtations with a campaign last year but because the most wired-in Democrats from Washington, D.C., to Chicago to Los Angeles expect him to be a paramount figure in the 2024 election. This is in part due to his work in Illinois legalizing marijuana and raising the minimum wage and banning assault weapons, all while balancing the state’s budget and plowing resources into infrastructure projects. But it is perhaps more because of his willingness to use his enormous fortune. A Hyatt Hotels heir worth over $3 billion and the country’s richest officeholder, he’s spent hundreds of millions on Democratic candidates and causes (including his own) in recent elections. His status is thus politically complicated as both crucial ally to Joe Biden and potential successor if things go awry.

This is not lost on the president, who paused in a room full of donors in June to thank Pritzker before unspooling his fund-raising spiel. Pritzker, Biden confided to those in Chicago’s JW Marriott, “did more in 2020 to help me get elected president of the United States than just about anybody in the country. And that’s a fact.”

In the spring, Biden had invited Pritzker to join a clutch of influential and munificent string-pullers in D.C. for a secret tactics briefing–slash–fundraiser ahead of his campaign launch. Then, after making his bid official, he called Pritzker again, this time as part of a core group of governors he hoped to rely on politically. The pair have since kept up a light dialogue about strategy, and Pritzker has open lines of communication with some in the West Wing’s inner circle; one of Biden’s first 2024 campaign hires, Quentin Fulks, is a former Pritzker lieutenant.

It wasn’t just DeSantis’s implosion — “You used those words!” he said, grinning — that cheered him the afternoon we spoke. The day before, he’d brokered a “peace agreement” with local union chiefs, who committed not to strike at the Democratic convention next summer, and the Democratic National Committee agreed to contract union workers. The convention will be a Pritzker showcase: Before Biden chose Chicago as host, Pritzker personally assured him the city would have no trouble footing the bill of up to $100 million; it went unspoken that Pritzker isn’t expected to pay for it personally, though he could if needed.

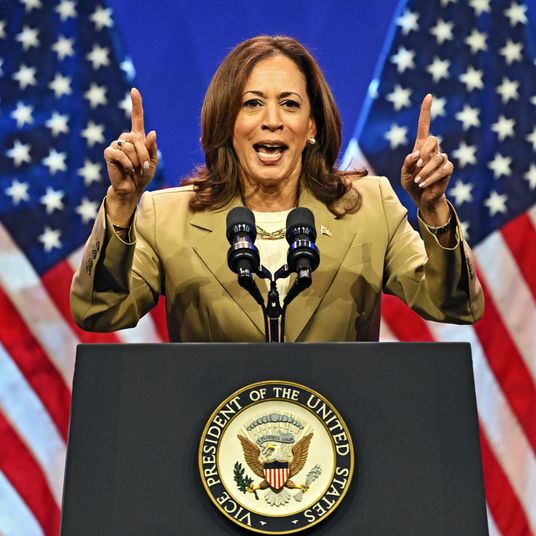

This comfortable understanding between the two is relatively new. Last summer, when Biden was on much shakier political ground, Pritzker seemed to test the “What if?” waters. He visited New Hampshire, traditionally the site of the first presidential primary, and told an interviewer “it’s certainly possible” Biden could face a primary challenge, though insisted he wouldn’t go up against him. He was also letting his frustration with Washington show. After the mass shooting at the Highland Park Fourth of July parade last year, he drew headlines for saying, “If you are angry today, I’m here to tell you to be angry. I’m furious. I’m furious that yet more innocent lives were taken by gun violence.” Democrats at the time had already been stewing that Biden hadn’t said more about the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and when Biden visited Chicago shortly after the draft Supreme Court opinion of Dobbs leaked, Pritzker used their shared motorcade ride to McCormick Place to insist, “We need you to be out there. You can’t have the vice-president doing all the talking; you are the president of the United States. You have to — every day, every day — go out and say, ‘We are working to protect women however, wherever, we can,’” the governor recounted to me a few months later. Before long, he was described in the New York Times as “Democrats’ SOS candidate.”

Still, with Biden showing no signs of forgoing a run for reelection, Pritzker has grown punchier on the president’s behalf. Onstage at Davos, just feet from Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, Pritzker celebrated the president’s record in spite of “some reluctant members of his own party.”

Pritzker was raised largely by an activist mother, Sue Sandel Pritzker, after his father, Donald, who’d been a major political financier, died of a heart attack when J. B. was 7. His mother died only a decade later following a turbulent and protracted fight with alcoholism. In rare quiet moments, Pritzker reminisces about going with her to LGBTQ+ and abortion-rights strategy meetings, door-knocking sessions, marches, and rallies. “Just the impression of your mother as somebody who’s carrying the room,” he recalled, “had a big effect on the way I view the world and the idea that I have a responsibility like my mother did.”

Those who know him best occasionally posit that this sense of responsibility explains his lack of preciousness when it comes to using his abundant resources for political causes. He is unapologetic about the political headway his donations and suggestions can make — electing Democrats is important, he says, so he’s doing what he can to help — and though he has yet to decide exactly what form his 2024 spending will take, he’s already been inundated with pitches from committees and super-PACs and from people suggesting he consider funding turnout-juicing projects like abortion referenda on swing-state ballots. Multiple people who’ve talked to him about the coming presidential election independently said that “he’ll do whatever it takes” to keep Trump (or a Trumpist) from winning. In last year’s midterms, that posture meant spreading donations to gubernatorial races such as his own (he spent more than any candidate ever has to boost a far-right opponent in Illinois’s GOP primary who he determined would be easy to beat) and to lower-profile but highly consequential contests like the election of a liberal judge to tip the Wisconsin Supreme Court to the left. “From a financial perspective, it would be hard to find a hard-core Democrat who J. B. hasn’t helped,” said former Illinois congresswoman Cheri Bustos, who got her own significant boost from Pritzker after finding herself in political trouble when running the House Democrats’ campaign wing in 2020. “When you have money, it really does help. Who does he owe?” asked Bustos. Pritzker, she explained, is beholden to no donors but himself, so he approaches his job differently. “I think it’s liberating that he doesn’t have to spend one second in the call-time room.”

His straight-ahead approach to his financial influence is a practical attitude for a man who’s been around politics his whole life and whose level of involvement has been steadily increasing. Early in his career, he worked as a staffer for Illinois senator Alan Dixon, whose chief of staff was Bustos’s father. Then Pritzker ran an investment firm and tech incubator for years, and his own failed congressional race in 1998, before he gained national recognition as a donor to watch in 2008. He backed Hillary Clinton when his sister, Penny Pritzker, supported Barack Obama and was rewarded with a post as Commerce secretary in Obama’s second term.

It’s a mistake to read Pritzker’s sway at home as solely coming from his wallet, but it’s lost on no one that if Biden were to step aside and Kamala Harris were to falter, Pritzker would be without peer in his ability to fund a last-second campaign. He has proved a surprisingly adroit pol with a loyal following, developing a penchant for creating mini-moments that captivate Twitter. Take, for example, the time he caught a lobbed Jell-O shot and downed it at a recent Pride parade or the fact that lefty shitposters have fun treating him like a conquering hero online because of their constant pleasant surprise with his aggressive progressivism. As one tweeted last summer, “He is enormous, doesn’t come off as particularly intellectual, and has good instincts.”

He has in recent months also leaned into trumpeting his own accomplishments in Illinois as a counterpoint to chaos in Republican-run states, especially DeSantis’s Florida and Greg Abbott’s Texas. This has, in part, meant engaging in the culture wars. After DeSantis, whom Pritzker had previously called “just Donald Trump with a mask on,” said he would ban AP African American Studies classes in his state, Pritzker wrote an open letter to the College Board insisting that Illinois wouldn’t stand for the body engaging in a “watering down of history” in his state to appease Florida. Figuring he has the business-world credibility that many other Democrats lack, he has since considered taking an even clearer message to industry leaders around the country: Companies will find moving to red states to be unsustainable as employees flee book bans and abortion restrictions.

Still, his national case has been overshadowed by accomplishments of ambitious and attention-eager Democratic governors in swingier states (like Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer and Pennsylvania’s Josh Shapiro) and by the headline-hungry antics of others (like California’s Gavin Newsom) just as their party seems desperate to anoint a new class of Next Big Things absent an especially galvanizing presidential candidate. Pritzker has bristled at the notion that his accomplishments are more easily won than some of his colleagues’ because Illinois is a blue state, pointing out that it has until recently had Republican leadership. His predecessor was a Republican, and Pritzker’s margin for error in the legislature has grown in part because — “Yeah, I helped elect them!” — he set out to increase his roster of allies. Meanwhile, hardly a week goes by without Whitmer insisting she isn’t running for president … yet. But Pritzker maintains that he’s perfectly happy about the positive coverage surrounding Whitmer and others — perhaps not least because he knows how they got there. “I helped her get elected,” he says, shrugging. “And I helped her get reelected and I helped them get people elected to their legislatures, too.”