Remember Wendy Davis? For a brief moment in 2013, Davis, then a Texas state senator, captured the nation’s attention with a dramatic gambit. The Democrat filibustered an anti-abortion bill, spending 13 hours on her feet while reading research and testimonies from women who opposed the legislation. (A doctor had inserted a catheter into her bladder so she could accomplish the feat.) Images of Davis in her pink sneakers spread across the internet. Writer Sally Kohn would later call the shoes “a talisman of feminism and political voice and literally standing up for what’s right.” By the end of the evening, pro-choice activists had crowded into the rotunda of the state capitol, and prominent Democrats had signaled their support for Davis in public. Thanks to her efforts, the bill died.

As New York Times reporters Elizabeth Dias and Lisa Lerer document in their new book, The Fall of Roe: The Rise of a New America, liberals thought that with Davis on their side, “they were watching democracy at work.” She’d given them reason to hope, and they believed that she would ultimately triumph over their Republican foes. “A new Texas and a new America were here,” write Dias and Lerer, and for a handful of weeks that seemed true. Davis became a meme: In one, she was America’s very own Daenerys Targaryen. At the Newseum in Washington, then–Planned Parenthood president Cecile Richards hosted a cocktail party for supporters with condoms as party favors. Then the hammer fell. Just under three weeks after Davis finished her filibuster, Republicans called a special session. This time, the bill passed. Dias and Lerer write that Planned Parenthood announced that it would close three clinics on the day Governor Rick Perry signed the bill.

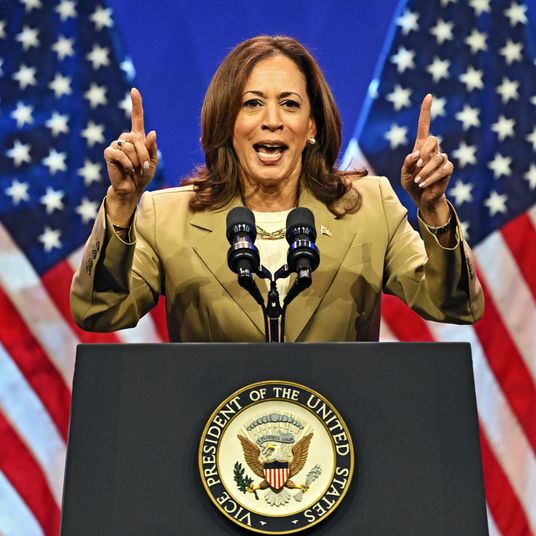

Even after S.B. 5 passed, Richards believed their fight had “woken up a sleeping giant” in the form of pro-choice voters in Texas. It was a somewhat reasonable conclusion at the time. Barack Obama had just won reelection, Davis had generated intense public interest, and in national polling, the public supported the right to legal abortion. But look closely at this façade, as Dias and Lerer have, and the cracks are evident. The Obama presidency gave way to four years of Donald Trump, who appointed three conservative jurists to the Supreme Court, who in short order overturned Roe v. Wade. A Democrat is president again, but he faces a difficult race against Trump. Will the fall of Roe awaken the sleeping giant at last?

Voters say overwhelmingly that the Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe was wrongly decided, and public outrage has helped Democrats outperform expectations in the elections since that ruling. This year, Democrats are counting on abortion to help Biden win a second term. But then as now, overconfidence can be fatal.

The Fall of Roe unfolds like a horror story. Danger lurked outside the cabin door, but the threat was never fully perceived by those who lived within. Dias and Lerer depict a liberal Establishment that behaved as though it had permanently won. “Roe loomed so large in American life that it was almost impossible to imagine that it could disappear,” they write. “Every election Democrats and their allies in the abortion rights movement warned voters about the potential consequences to abortion rights, should they vote Republican,” but they didn’t really believe that Roe would one day fall. Yet as institutions like Planned Parenthood grew flush with cash, activists closer to the ground and who were more exposed to danger warned of trouble. A constellation of “smaller, largely Black and Hispanic abortion-rights organizations” knew that restrictions had already eroded the right to abortion. Though the big abortion-rights groups considered the Affordable Care Act a major success, the law reaffirmed the Hyde Amendment, which banned federal funding for abortion care and mostly affected poor women.

“To the Black and Hispanic reproductive justice activists, the new health care law, which left the Hyde Amendment intact, was a sign that the biggest organization in their world was willing to trade away their rights,” write Dias and Lerer. Democrats didn’t have the votes to end Hyde, as Dias and Lerer point out; the party’s big-tent approach to abortion had seen to that. As a result, activists who worked outside the rarefied environment occupied by Planned Parenthood and its peer organizations often scrambled for resources in order to provide care. Three years after the passage of the ACA, when Planned Parenthood introduced “a new messaging campaign” which “dumped the decades-old terminology of pro-choice for a broader approach,” tensions deepened. “The new messaging frustrated reproductive justice movement activists who had always believed that the fight for abortion rights couldn’t be severed from the economic, justice, housing, and maternal health care struggles that disproportionately affected the reproductive lives of women of color,” they report. “Now, it felt like Planned Parenthood was stealing their approach and acting like it was its own.”

Meanwhile, powerful liberals still didn’t quite understand what threatened them. Not only did the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg refuse to retire in time for Obama to appoint her replacement, she told Elle that on abortion, the national pendulum had swung “about as conservative as it will get.” Ginsburg wasn’t totally wrong: Roe was the victim of a far-right minoritarian movement that succeeded not by capturing the vote, but by capturing the Supreme Court. But her observation, which is repeated by Dias and Lerer, combined with her decision to die on the court, suggests that Ginsburg was perhaps as out of touch as the liberal Establishment that lionized her.

Ginsburg wasn’t alone. “We didn’t take it seriously and we didn’t understand the threat,” Hillary Clinton said in an interview exclusive to the book. “Most Democrats, most Americans, did not realize we are in an existential struggle for the future of this country.” That may well be true, but it’s an infuriating admission from Clinton, whose defeat in 2016 helped cost liberals the court. She continues to attribute her loss to her gender, according to Dias and Lerer, and while that’s at least partially right, she is eager to blame everyone but herself. Once James Comey announced the reopening of the Clinton email investigation toward the end of the campaign, “the people, the voters who left me were women,” she said. “They left me because they just couldn’t take a risk on me, because as a woman, I’m supposed to be perfect. They were willing to take a risk on Trump, who had a long list of, let’s call them flaws, to illustrate his imperfection, because he was a man, and they could envision a man as president and commander in chief.” Women in politics face unfair standards, but Clinton’s habitual refusal to look inward grows tiresome. If she’s going to speak, she could at least say something new.

Still, Dias and Lerer were right to interview her. We benefit from seeing our leaders as they truly are. In The Fall of Roe, liberalism’s most iconic women are critical failures too. Pantsuit Nation feels like a collective hallucination now. So does the Notorious RBG. I wonder what so many of us once saw in an unelected cleric who was friends with Justice Antonin Scalia. Her accomplishments were real; her dissents made her beloved. But in judicial terms, what is a dissent but an admission of defeat?

Anti-abortion activists faced their own challenges. Their views were unpopular and they had allied themselves with the GOP, a party that struggled, often, to explain its opposition to abortion in a way that activists found to be persuasive or meaningful. In 2013, the Susan B. Anthony List (since renamed Susan B. Anthony Pro-life America) “was a minnow in a city of sharks,” Dias and Lerer write, with an annual budget of $7 million compared to Planned Parenthood’s billion. Under the leadership of Marjorie Dannenfelser, though, SBA would become a powerhouse. Dannenfelser and her allies had conviction, and they had plans. While liberals arguably slept, the most radical adherents of the anti-abortion cause carefully strategized a multipronged assault on the right to end a pregnancy.

One was David Daleiden, who, with his six-foot black-throated monitor lizard in tow, crossed the country speaking with anti-abortion extremists like Troy Newman, the president of Operation Rescue. Daleiden would later release a series of misleadingly edited videos that falsely implied that Planned Parenthood trafficked “baby body parts” for profit. Daleiden belonged to a new generation of activists who had more in common with Newman than with mainstream anti-abortion Christians and their “incremental” tactics. Yet the mainstream needed them in order to continue its work, and Daleiden’s videos allowed them to mount a spectacular attack on Planned Parenthood. A House hearing followed, and conservatives called on Congress to defund the organization. The false notion that Planned Parenthood traffics fetal remains has become an article of faith within the anti-abortion right. In the anti-abortion movement, there has never been much daylight between the mainstream and the fringe. The idea that abortion is murder is extreme by default. Now, though, the mainstream has given way entirely to the Daleidens in the movement, a shift that is visible also in the Republican Party and the broader conservative project. In an email at the time, Dannenfelser praised Daleiden’s work. “Just expressing gratitude again. God is good and you guys planned this masterfully,” she said.

She’d soon have other reasons to be grateful. As the movement shifted to the right, a sophisticated legal strategy was taking shape. The end of Roe was in sight. Dias and Lerer provide a great public service by documenting this legal initiative at length, identifying key players like lawyer Misha Tseytlin, the former Wisconsin solicitor general who clerked for then-Justice Anthony Kennedy. Nevertheless, they overstate the degree to which this is untold history. Though Tseytlin isn’t a celebrity, his anti-abortion views are known, and close observers of the Christian right had long warned of rising extremism and the influence of groups like SBA and the Alliance Defending Freedom, or ADF.

Roe may be gone, but the movement that killed it will not rest. As Dias and Lerer write, the fight against legal abortion is tied inextricably to the fight for America’s soul. Dannenfelser and Leonard Leo, who leads the Federalist Society and who orchestrated much of the right’s judicial successes, are united by more than their opposition to abortion. They believe in a vision of American womanhood that is at odds with the liberal feminism which raised up Davis and Ginsburg and Clinton. The goals of the Christian right are even further afield from the socialist feminism I now embrace, which strives for reproductive justice: the right to abortion, free and on demand, alongside the right to housing, to healthcare, to food. To be a socialist feminist is to fight a war on all fronts. The right is no less proactive, as Dias and Lerer make clear.

Not long after Dobbs put an end to Roe, Justice Samuel Alito delivered a fiery talk in Rome. There, as Dias and Lerer recount, he told audience members that there was a “growing hostility to religion, or at least the traditional religious beliefs that are contrary to the new moral code that is ascendant.” Alito urged them to action. “People with deep religious convictions may be less likely to succumb to dominating ideologies or trends, and more prone to act in accordance with what they see as true and right,” he told them. “Civil society can count on them as engines of reform.” In the first months after Roe, when Leonard Leo accepted an award from the Catholic Information Center, he warned onlookers that the fight continued. He called his opponents “a progressive Ku Klux Klan” for their alleged anti-Catholicism and added, “They are conducting a coordinated and large-scale campaign to drive us from the communities they want to dominate … They control and use many levers of power.” Dias and Lerer write that Leo’s progressive foes could “easily” apply the same description to his own work. Regardless, Leo is right about one thing. The fight does go on.

Two years before the fall of Roe, Wendy Davis told Elle that she still has her old pink sneakers. She was running for office again that year, this time for Congress. She lost to incumbent Chip Roy, a Republican who currently boasts an A+ rating from SBA, Dannenfelser’s group. Davis is out of politics now; Roy is ascendant. A November victory for Joe Biden is far from assured, and he is not the standard-bearer that many abortion rights supporters had hoped to elect. Dias and Lerer write that in 2023, “as he headed into his reelection campaign, Biden still had not held a formal White House meeting with the heads of the abortion-rights organizations.” Democrats still speak of codifying Roe, though it should be clear by now that Roe on its own was never enough. And while liberals recover from their shock, the Christian right plans for a national abortion ban. If women are to secure their fates, they need more than liberalism can offer. Icons are no replacement for conviction and strategy. “Dobbs was now the guiding force for the country’s laws,” write Dias and Lerer. “But the mass outrage that met the ruling showed that the country had not resolved the essential question intertwined with the long national battle over abortion: What rights is a woman owed?” The Christian right has an answer ready. Its opponents must have one too.