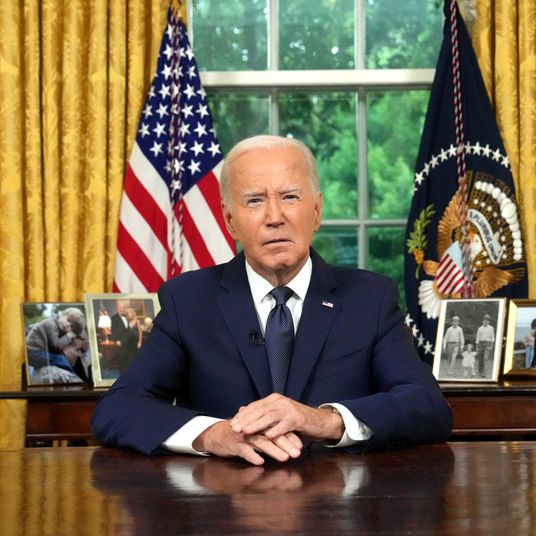

In November 2021, top Biden-administration officials gathered in the residence of the White House as the House was about to finally vote on the Build Back Better legislation that had been their objective since taking office. The only person missing was Vice-President Kamala Harris, who had already left the White House for the day. Eventually, a staffer caught wind of the gathering and she had to leave home and go back to work.

This revelation is one of many in Franklin Foer’s new book, The Last Politician: Inside Joe Biden’s White House and the Struggle for America’s Future, which is the result of two years of reporting inside the Biden administration. It is the deepest dive so far into a White House that has been far more guarded with the press and averse to leaks than past administrations. The book, which has been eagerly anticipated by officials in Washington, comes out on Tuesday.

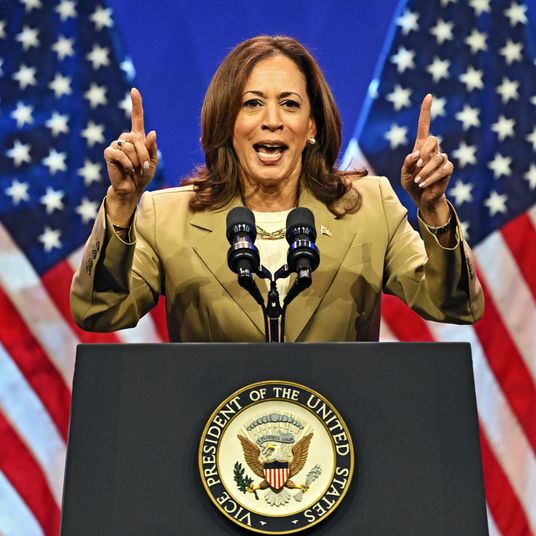

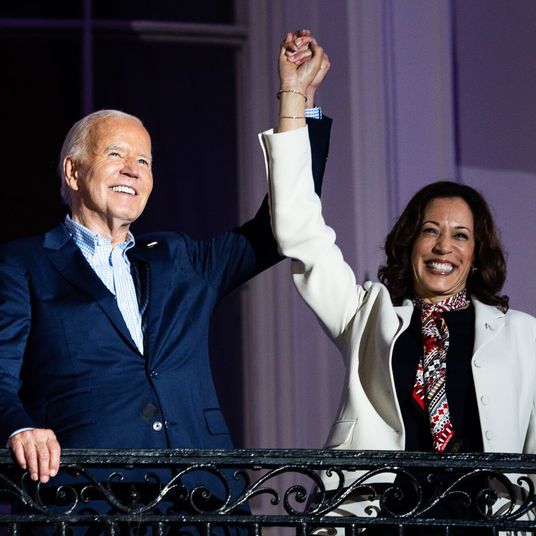

The new book depicts Harris as having “rabbit ears” — acutely sensitive to “any hint of criticism” and “instantly aware” of the slightest bit of discontent. The result, Foer reports, is that Harris “lets the criticism guide her” and thus fails to rack up meaningful achievements.

Foer, an author and staff writer at The Atlantic, describes an administration where Harris is a comparatively minor player and seemingly manages to always put the wrong foot forward despite her best efforts. In one meeting with Republican senators intended to entice them to support bipartisan infrastructure legislation, she ended up chiding Roger Wicker of Mississippi about the state of the economy under Donald Trump, leading to Cabinet secretaries wanting to alternately pump their fists and cover their eyes. In another Oval Office meeting, this time with Joe Manchin shortly after Harris did a television interview with a West Virginia station that Manchin interpreted as a power play, she seemingly snubbed Manchin, not offering a handshake or acknowledgment as she left the room so the West Virginia senator could meet privately with Biden.

Harris’s lack of achievements was not the result of her not having the capacity for the job, according to the book. Foer takes pains to note that her contributions to meetings were often incisive, and she “asked questions about equity that tended to be neglected.” Instead, it was a result of a personality that prized preparation for every possible aspect of an issue, as she constantly read books and her briefing materials while pressing those assigned to brief her. As Foer put it, “in her disciplined desire to prepare, she would become undisciplined about her own calendar.”

She also is characterized as having a deep insecurity about her historic place as the first Black woman to serve in her position, which helps drive her relentless preparation. Harris initially insisted that she did not want her portfolio to include “women’s issues or anything to do with race.” At the same time, she wanted her staff to be majority female and her office run by a Black female chief of staff. The result was that Biden’s then–chief of staff Ron Klein concluded the vice-president was “making life excessively difficult for herself.” Since then, Harris has gone on to become a top surrogate for the Biden administration both on voting rights and abortion rights in the aftermath of the 2022 Dobbs decision.

There is also a sense, throughout the book, of Harris being a neglected figure in the administration. Unelected Biden aides like Klain, Mike Donilon, and Steve Ricchetti are depicted as far more central to the White House’s functioning than the vice-president. She is a minor character who has little role in the administration’s domestic and foreign policy. The one moment that she intrudes on the latter is when she speaks at the Munich Security Conference in 2022 on the eve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in what Foer describes as Biden giving her “a public vote of confidence.” There, Harris followed in the footsteps of other administration officials attempting to convince Ukrainian president Volodymr Zelenskyy to seriously prepare for Russia’s upcoming onslaught.

Harris’s minimized role is a sharp departure for modern vice-presidents, whose office was infamously described by Franklin Roosevelt’s first vice-president, John Nance Garner, as “not worth a bucket of warm piss.” It only became a more powerful position in the past few decades — no vice-president even had a West Wing office until Walter Mondale under Jimmy Carter.

Although Dick Cheney was infamously considered the power behind the throne in the George W. Bush administration, other modern vice-presidents too have had important roles. For all of the tensions between Biden and Barack Obama, it would be difficult to write a history of the first two years of the Obama administration without mentioning Biden’s influence as a key congressional negotiator and behind-the-scenes figure. And even though Donald Trump ended his presidency by egging on a mob that chanted “Hang Mike Pence,” it would be hard to chronicle his administration without mentioning Pence’s influence in trying to manage the volatile Trump.

That’s not the case in this administration, according to Foer. Then again, Biden did promise to return American politics to normal, and that may not just have meant ending a pandemic and being restrained on social media. Perhaps it also meant restoring the vice-presidency to its more traditional, less critical role in the U.S. government.