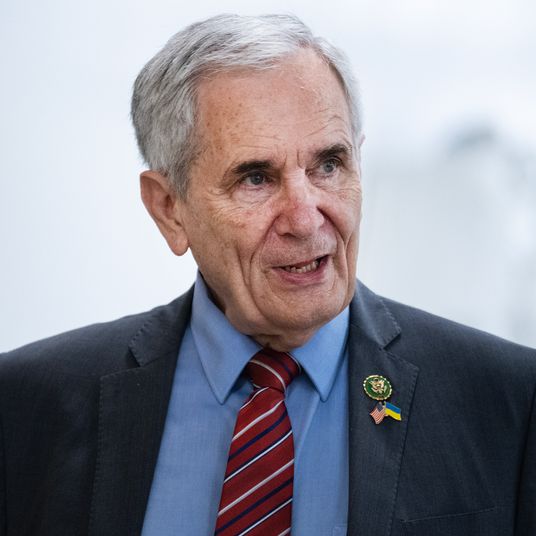

Mondaire Jones introduced himself to New York’s Democratic Establishment by lunging for its jugular. In 2020, he announced what looked like an improbable primary against Nita Lowey, a 30-year House veteran and co-chair of the state’s congressional delegation. Just one cycle prior, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez had unseated 20-year incumbent Joe Crowley in Queens, and it got Jones’s attention, inspiring him to run his own insurgent campaign in the Hudson Valley.

Lowey decided to retire rather than risk an upset, and seven other Democrats jumped in to enter the race. Jones captured the progressive lane with the endorsements of Ocasio-Cortez, a graduate of Yorktown High School in the district, and Bernie Sanders. Young, Black, and openly gay, he was soon hailed by left-wing outlets from Democracy Now! to Mother Jones as proof of the next generation’s challenge to the status quo. Just to the south, Jamaal Bowman, another young Black lefty, was running to unseat Establishment stalwart Eliot Engel with the endorsement of the Democratic Socialists of America.

As Black Lives Matter protests stretched out that summer, Jones appeared at events with Bowman and flexed his endorsements in mailers blasted throughout the district, touting his support for a Green New Deal and Medicare for All. Jones also supported defunding the police, as he put it in a joint appearance with Bowman on a panel: “We have to make sure that we have a broad conception of systemic racism. It cannot just be confined to individual instances of police officers killing unarmed Black and brown people in this country,” he said. “And of course, we need to end mass incarceration and legalize cannabis and defund the police.”

Three years after he won that race, and after effectively being pushed out of his district only to lose a bid to represent Brooklyn, Jones launched his third bid for Congress with a campaign ad that shows him in a different light: shaking hands with the police chief of Pound Ridge, who says, “I’ve worked in law enforcement in the Hudson Valley for just about 40 years. We do not get the funding they get in the city. Mondaire Jones listened and funded the police.”

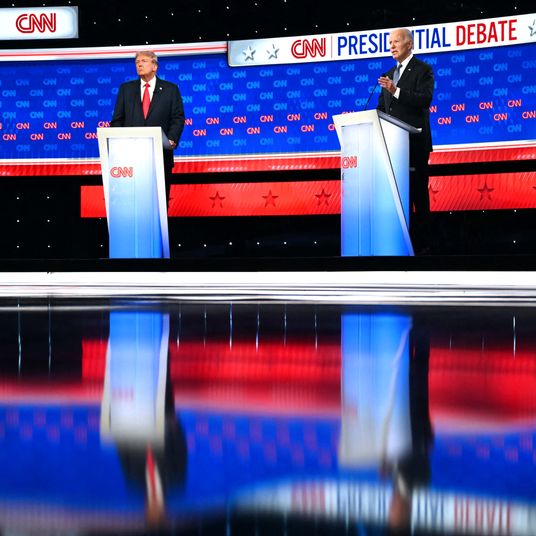

While picking at his gyro platter at a Greek restaurant in Tarrytown last month, Jones explained that what he really meant back in 2020 was a reallocation of money from police funds to mental-health services. Either way, last year the GOP knocked out four New York congressional incumbents and took control of the House, thanks, in part, to campaigning against some Democrats’ support of defund and cashless bail. “On the scale of really stupid slogans that don’t convey what it is that you intend, it has got to be extremely high on the list,” he told me.

After entering politics by spurning the centrist Democratic Establishment, Jones now seems like he wants to be a part of it. But as he has returned to Westchester County to launch his third bid for Congress, Jones is drifting—or pivoting, depending on whom you ask—to the middle in order to campaign as the sole candidate who can turn the district blue again. But the Establishment is not so easily wooed, and some members have already lined up behind his opponent Liz Gereghty, the sister of Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer.

In 2017, Jones was scouted as a fresh young talent who could run for the State Senate as a progressive firebrand to primary one of the stale incumbents who made up the Independent Democratic Conference, which teamed up with Republicans in Albany to block progressive legislation. He had a compelling personal story, growing up in public housing as the son of a single mother who suffered from mental illness and relied on her parents, a janitor and housekeeper, to help raise him. “I’m running … to represent the same people whose homes I watched my grandmother clean,” he said throughout the race. Now, when Jones tells voters he is from Spring Valley, they often raise their eyebrows, shocked not only that he made it out but that he made it to Congress. Last month, the water in the public-school system he attended was declared unsafe to drink.

After Stanford, Jones did a yearlong fellowship in the Obama Justice Department before going on to Harvard Law School and then a position at a white-shoe law firm. But after a few years, he took a steep pay cut to work in the Westchester County Attorney’s Office under John Nonna. “I knew he wanted to run for office eventually,” Nonna said. “But it was quite a surprise when he walked into work one day and said he was going to challenge Nita Lowey.”

After winning 41 percent of the vote in his primary, Jones was added to a group chat with the newly elected Bowman by Ocasio-Cortez, who gave them both advice on staffing and security protocols. He immediately joined the Progressive Caucus, though he pledged he wanted a “fantastic relationship” with Speaker Nancy Pelosi. Once in office, he co-sponsored bills to implement universal child care and expand the Supreme Court. While he doesn’t reject the term progressive, which he has called himself in the past, he now thinks a more accurate word might be “pragmatist.”

“There are people who say things like ‘Billionaires should never exist,’ and I think that’s so silly because so long as we are providing a certain standard of dignity for everyone in our society, what does it matter that billionaires would still exist past that point?” Jones said. “I mean, these slogans are oftentimes intellectually unserious.”

He said that it was perhaps inevitable that people would project their own leftmost positions to the young, gay Black outsider, but to hear Jones tell it, those saying he’s changed might just be unfamiliar with his consistent voting record.

“Progressives give me shit for wanting to lift the cap on the SALT deduction, or wanting to fund the police, or … my pro-Israel stance, but I’m not changing,” said Jones. “That’s who I am. And for what it’s worth, my district also supports me.”

Left-wing Democrats had dismissed the move to lift the cap on how much property tax can be exempted from federal taxes as a handout to the rich, but Jones introduced a bill to lift it before he was even sworn in. In another break with his lefty allies, Jones said he would have gladly attended the Israeli president’s address to Congress last month, which Sanders, Ocasio-Cortez, and Bowman boycotted. Since then, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee started recruiting a primary challenger to Bowman. As for Jones, he said, “I’ve got a great relationship with AIPAC,” and his team would not say whether he would endorse the AIPAC-backed challenger or Bowman, only that Bowman doesn’t need his endorsement. (The 17th District where Jones is running has the largest Jewish constituency in the country.)

But it was not the left that Jones sparred with when he first arrived in Congress. During his first month in office, he pressured then-Governor Andrew Cuomo to oppose the expanded operation of a power plant in the Hudson Valley that burns fracked natural gas. His team circulated a letter to Cuomo throughout the New York congressional delegation to collect signatures, but Sean Patrick Maloney didn’t sign on. Maloney, whose Establishment roots go back to Clinton’s White House, had been endorsed by the power plant’s union, and members of his team made it clear to Jones’s that the opposition was not only inconvenient but reflected a lack of deference that was inappropriate.

Eventually, Jones gave in and dropped the issue. But it wouldn’t be the only time that Maloney bullied Jones into submission.

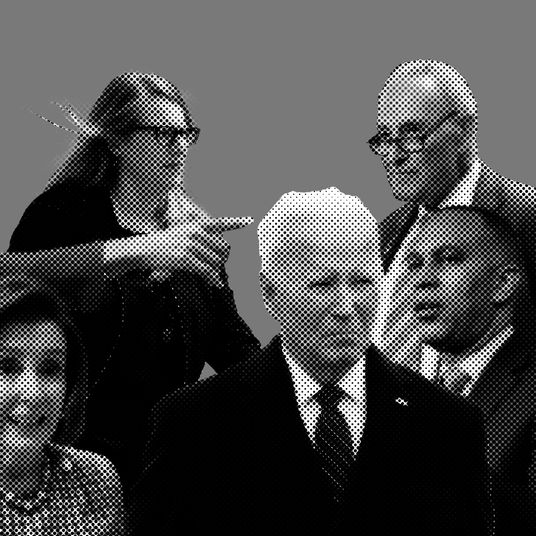

In May 2022, a court-appointed special master redrew New York’s congressional maps, placing the hometown of Maloney, who was by now the boss of the powerful Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, in Jones’s district. Without giving Jones a heads up, Maloney announced he would run in the newly drawn 17th District. Despite the optics of a powerful white Establishment figure trying to push aside Jones, Democratic House leadership approved the decision. “We’re very proud of Sean Patrick Maloney,” Pelosi told reporters right after the power grab.

Faced with the prospect of running against the man in charge of funding for every Democratic congressional campaign in the country, Jones looked elsewhere. At first, according to three sources, he weighed a primary against his neighbor to the south, Bowman, conducting polling to see how Jones would fare. The two have since stopped doing events together, which they frequently did after winning their first primary.

Jones decided instead to look for an open race and moved to Brooklyn to establish residency for the new 10th District. After trying and failing to get the left-wing Working Family Party’s endorsement, he was unable to consolidate a splintered progressive field. Pelosi threw him a bone and endorsed Jones, but Dan Goldman, the wealthy veteran federal prosecutor who received the backing of the real-estate lobby and the endorsement of the New York Times, won. As for Maloney, he was humiliated both as DCCC chair and as candidate after losing to Republican Mike Lawler, whom Jones is now trying to unseat.

Just two years after he shot to fame, Jones found himself on the sidelines, pushed out by the Establishment of his own party. And almost as soon as he moved back to his district in the riverfront town of Sleepy Hollow, he ran into the Establishment again in the form of Liz Gereghty.

Gereghty’s run for Congress is being received with more national support than might otherwise be expected of a woman whose highest office has been trustee on her local school board. She’s earned donations from California representative Eric Swalwell’s PAC, the vice-chairman of the Detroit Pistons, and the CEO of Visa, who both live in California, as well as the CEO of Zillow in Seattle.

Learn her family name, though, and things begin to make sense. Before she became Liz Gereghty, she was Liz Whitmer. Now, as she makes her first bid for Congress, she has rebranded herself Liz Whitmer Gereghty, and she’s banking on her family’s national political connections. But she takes issue with people asking if she’s using her original name to capitalize on her sister’s clout.

“You know what, here’s the thing — and this is what women will tell you — like, no matter what choices we make, they’re always going to be wrong according to someone,” she said in an interview.

Gereghty added that she was Liz Whitmer longer than she was Liz Gereghty, although she declined to explain why she didn’t use Whitmer in her school-board elections in 2019 and 2022. Before then, she owned a knickknack store called pOp in Katonah, selling a wide variety of resistance kitsch: soda with labels like “Make America Grape Again,” Barack Obama action figures, Catholic iconography candles featuring Robert Mueller, and temporary Ruth Bader Ginsburg knuckle tattoos that spell “Dissent” with a letter for each finger.

In June, she hosted a fundraiser with her sister Gretchen in Tarrytown, though she said the governor was only at the fundraiser because she happened to be in town for Gereghty’s son’s graduation party. But the evite suggests it was an intentionally planned sister-themed event. “She’s making phone calls to my former colleagues and to some people in the district, asking them to support her sister,” Jones complained, before qualifying, “which is her right to do.”

The phone calls have helped Gereghty’s fundraising catch up to Jones. Since announcing in May, she has collected just over $400,000 in donations, most of it from out-of-state donors, compared to the $500,000 he has raised since announcing last month. Gereghty has also received the endorsement of EMILY’s List, a PAC that endorses pro-choice women candidates, while Jones has the backing of some 122 mayors, supervisors, and other local officials. According to a recently released poll commissioned by his campaign, Jones leads Gereghty by 43 to 8 percent, with 51 percent undecided a year before the primary.

Gereghty is reluctant to take digs at her opponent, but she did suggest Jones’s previous use of “defund the police” was reason enough for voters to choose her instead. If that isn’t, then, in her opinion, Jones’s move to Brooklyn ought to be, suggesting he abandoned the district. “Anyone paying attention to what happened last year knows that I didn’t just wake up one day and decide not to represent my district,” Jones told me.

As Gereghty’s campaign bids for support from party leadership, Jones earned the tacit approval of one of New York’s most powerful Establishment figures when he received the endorsement of the Congressional Black Caucus. “They would not endorse Mondaire unless Hakeem said they could,” an operative told me, referring to Hakeem Jeffries, the House minority leader from Brooklyn who has a reputation for his intolerance of the left. In 2020, Jones criticized the CBC for not endorsing him until right before the primary, but this cycle he has received its approval more than a year out.

The endorsement will probably mean more for Jones’s reception in Washington than for his reputation at home in his district — not many voters make decisions because of caucus endorsements — but it has now officially allied him with the very Establishment he began his career antagonizing.

“I have never been more confident that these labels mean very little,” he said.