The 2022 election had just ended, and the Wisconsin Democratic Party’s main bank account was dipping into six-figure territory, the result of a spending spree on a slate of tough statewide races and a huge array of local ones. For the most part, the results had been better than expected: Governor Tony Evers had been reelected, as had Attorney General Josh Kaul, though Lieutenant Governor Mandela Barnes had fallen agonizingly short in his attempt to unseat Republican senator Ron Johnson. Republican had gained a supermajority in the state senate and came close in the assembly. Ben Wikler, the party’s chair, immediately started to make a new case to donors around the country — including plenty who’d already insisted they were tapped out — that a race just five months later carried truly existential stakes both for the future of democracy and for abortion rights.

The pitch worked, and by the time Janet Protasiewicz, a liberal Milwaukee County circuit court judge, won the primary for an open state supreme court seat in February, the party’s balance was back up to around $3.5 million. Wikler promptly sent Protasiewicz’s team $2.5 million of it, then returned to the phones. Some of Democrats’ biggest donors got the message: In March, Illinois governor and billionaire J.B. Pritzker pulled together a $5 million fundraiser. By the beginning of April, with just days left until the vote, the party had pumped around $9 million into Protasiewicz’s campaign, enough to fund an onslaught of ads that helped drown out her far-right opponent, former state supreme court judge Dan Kelly.

If the political media was focused on Donald Trump’s arraignment in Manhattan on April 4, there’s a reason its eyes swung to the Midwest by the end of the evening. In a state defined by nail-biter elections — four of the last six presidential races there were decided by less than a point — Protasiewicz recorded an 11-point victory. The Democratic turnout surge not only swung control of Wisconsin’s top court to liberals but marked a new moment of hope for Democrats in the ultimate battleground state. In recent years, their methodical attempts to claw back power with an ignited voter base and a rejuvenated political infrastructure have met some of the most intractable, conspiracy-minded, and anti-democratic Republican resistance anywhere.

And as both parties have been quick to remind voters, what happens in Wisconsin rarely stays there. The tipping-point state in both the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, Wisconsin has had a singular recent journey. It has both resisted the last decade’s rightward drift of its neighbors in Indiana and Iowa and also the leftward inching of Michigan and Pennsylvania or the more pronounced liberal sway of demographically similar Minnesota. The latter is partly due to anti-labor policies put in place by conservative governor Scott Walker but mostly because of Republicans’ success in redistricting after the 2010 elections, resulting in a gerrymander so aggressive that in 2018 Democrats won 200,000 more votes than Republicans but just one new seat in the assembly. When Walker lost that year, Republican lawmakers stripped the incoming Democratic governor and attorney general of important powers before they even got to work. Two years later, Wisconsin Republicans became as insistent as any in the country in their efforts to overturn Biden’s victory.

Protasiewicz’s win may signal a new era of Wisconsin politics. For one thing, the court’s new orientation is likely to shift the party’s thinking about its future opportunities. In 2024, “we don’t have to worry that the result is going to be overturned by the state’s highest court, which focuses the mind on just winning,” said Wikler. More immediately, last year’s Dobbs decision reactivated an 1849 Wisconsin law banning abortion. The newly left-leaning state supreme court is likely to hear a challenge to the ban and is expected to overturn it. “We believe the 1849 abortion ban is unconstitutional, we believe the extreme partisan gerrymander is unconstitutional, and I think we have significant opportunities moving forward to challenge those statutes,” said Greta Neubauer, the Democratic minority leader in the state assembly. The court may soon hear a challenge to the Republican legislative maps that have given the state GOP so much power, as Democratic leaders shift to an offensive posture for the first time in years.

The victory wasn’t just the product of campaign cash, of course. Protasiewicz ran explicitly on expanding and protecting the right to abortion, running a barrage of ads about the issue while Kelly tried changing the conversation to focus on crime. As canvassers spoke with prospective voters, the issue was inescapable. “I heard very regularly about abortion on the doors from people it directly impacted,” said Neubauer, who is from Racine. “People were worried about their kids and grandkids. People lost a concrete right that they counted on in this state.” It’s not the first time abortion has swung a race in Wisconsin. In 1990, Democrat Jim Doyle unseated a Republican attorney general after the incumbent signed onto an amicus brief calling for the overturning of Roe in the U.S. Supreme Court. But Doyle, who later became governor, said the scale of outrage today was something entirely new: “It’s hard to pick out another issue that has motivated people like this, not since the Vietnam War.”

It was an unusually influential state-party organization that rode that wave. It is rare for such a group to successfully act as the centralized organizer and funder for multiple competitive statewide campaigns independent of any one pol’s preexisting machine, especially in a top-tier swing state. Its run of results began in 2018. After Trump’s victory, Wikler’s predecessor Martha Laning surveyed alumni of Barack Obama’s campaigns for organizing advice and instituted a localized, community-focused model to replace the top-down one preferred by the Wisconsin arm of the Hillary Clinton campaign. In a good year for Democrats, Senator Tammy Baldwin was reelected and Evers narrowly ousted Walker. Still, it was close: Evers won by one point, compared to nine- and 17-point victories for the Democratic gubernatorial candidates in Michigan and Pennsylvania, respectively.

Wikler had recently moved back home to Madison after years in Washington as a senior official with MoveOn, and when he took over the state party in 2019, his goal was to build its digital organizing, outreach, and communications capacities. Quickly, he figured out that he had an opportunity to raise plenty of cash and attention online by engaging the resistance crowd. “We had been losing the race online in terms of impressions and engagements that Republicans were getting on social media, which in turn shaped mainstream press coverage,” he said. “Democrats were beleaguered in the public arena.”

In August 2020, after COVID hit, he collaborated with Madison’s own Bradley Whitford on a fundraiser based on a West Wing reunion and was surprised to raise over $160,000 — eight times the party’s expectation. He and his team then brainstormed how to replicate that success and brought in $4 million with a Princess Bride reunion that drew eyeballs and headlines around the country and kicked off a series that grew to include Veep, Parks and Recreation, Happy Days, and more.

Wikler’s emphasis on virtual engagement had come in handy when the pandemic hit, even as local Republicans tried to insist on in-person elections, as the party shifted to Zoom-based organizing and a get-out-the-vote strategy focused on absentee ballots. Yet when his staff studied what happened after Biden’s razor-thin victory, it found clearly that they had missed out by not knocking on doors in person, just like Democrats around the country. One analysis by another group that did door-knocking found that one out of every three households they contacted in-person reported that their contact information in the voter file was inaccurate, so they would have been unreachable online or by phone. Before long, the party was making plans to resume in-person organizing.

Then, the day before Wisconsin Democrats’ state convention in La Crosse, the U.S. Supreme Court stacked by Republicans overturned Roe. Democrats quickly stood up a public rally where Evers pledged clemency for doctors who were convicted of performing abortions and Kaul promised not to enforce the 1849 ban. If Beltway Democrats were wary of how to run on abortion immediately after Dobbs, Madison Democrats were not.

Money flowed in once again. Wikler’s argument with donors for the previous few months had been focused on the threat of election-denying Republicans seizing power to warp the 2024 election, but now abortion was animating both local and national politics. A 2015 change to the state’s campaign-finance rules had removed caps on individual donors to state parties and parties to state candidates, and the party took advantage far more than its opponents, or many other state parties, which often relied on distributions from the national organization. Among Wisconsin Democrats’ largest donors in 2022 were Silicon Valley philanthropist Karla Jurvetson, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, and George Soros, all of whom gave at least $1 million, as well as Michael Bloomberg. If not for that money and the backlash to Dobbs, “Republicans might have supermajorities in both chambers right now, instead of the smallest possible buffer,” said Wikler.

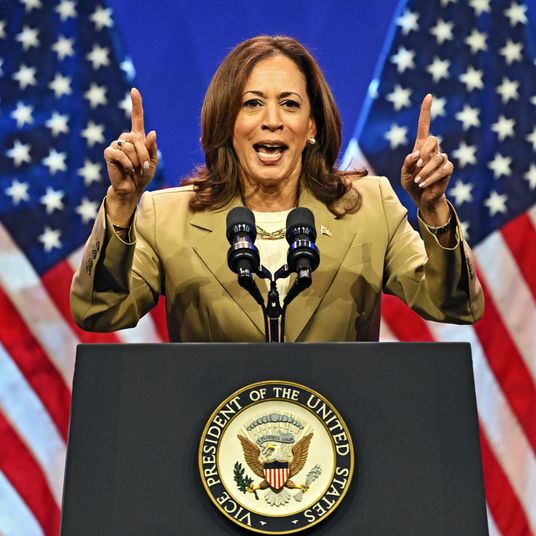

Still, those funds had almost dried up by November despite Wikler’s insistence on mentioning this spring’s supreme court race in his fall stump speech, calling it part of the same fight as reelecting Evers and competing for legislature seats. Party staffers had committed to stay on through early April for the contest, and it didn’t take long for that race to pierce the national consciousness, in no small part because of public pleas for support from Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, both Obamas, and Hillary Clinton. The party’s efforts to transfer money to Protasiewicz’s campaign helped her withstand a last-minute flood of Republican cash in support of Kelly — conservative groups outspent liberals in three of the final six weeks. (Since the judge’s campaign bought her ads directly, funded largely by the party, she was offered the lower candidate rate and was thus able to air far more than the outside groups that paid much more for less airtime.)

Protasiewicz used a mix of television, digital, and radio ads to defend herself against Kelly’s accusations that she was soft on crime, and hammering Kelly on abortion by painting him as an extremist who backed a total ban worked, too, especially in urban centers and some suburban targets. “The Republican Party has bent its efforts and engineered its work for decades now toward achieving this goal of banning abortion and ripping control of their own bodies away from half the population,” said Wikler. “Now they’ve got it and the public hates it.”

The sheer size of Protasiewicz’s double-digit victory has masked some of the more profound shifts implied by the results. (Powerful Democrats in the state had called Evers’s three-point win in 2022 a “landslide.) One is the return of battleground counties all over the state, which many had assumed to be trending red outside urban centers. In 2008, Obama carried 59 of 72 counties, and in 2016, Trump won 60. Protasiewicz took 27, but she cut into Kelly’s margins in conservative areas, even winning Brown County — home of Green Bay — which was once a swing county but was recently thought to be GOP-friendly and just a place for Democrats to minimize their losses.

That particular result has been attributed mostly to a revolt of suburbanites, but the starkest dynamic played out in Dane County, home of Madison and the University of Wisconsin and therefore a trove of young voters. More people voted in Dane County than Milwaukee County — which is almost twice as populous — and they backed Protasiewicz over Kelly by a 64-point margin. “This generation of voters is voting at higher levels than you have ever seen before,” said Dan Kanninen, a national Democratic strategist who ran Wisconsin operations for Obama in 2008. “And if you’re a Republican, you’re wondering: Did Trump plus the pandemic and the generational attitude changes create a class of young voters who are just better, more reliable voters? This election, to me, proves it.”

Wisconsin Republicans have largely come to the same conclusion, but there is no consensus among them about how to respond. Scott Walker, who now runs a conservative group aimed at young Americans, tweeted that such voters “are the issue” once the tallies were final. “It comes from years of radical indoctrination — on campus, in school, with social media, & throughout culture. We have to counter it or conservatives will never win battleground states again.” One right-wing Milwaukee radio host’s autopsy, published by a conservative think tank in the state, started to reckon with the new state of play: “Most pro-life Republicans are understandably nauseated by the idea that so many voters are so hellbent (no pun intended) on killing the unborn, but it is the political reality. For nearly 50 years, Americans were accustomed to the idea of legal abortions even if the thought of ever personally having a child aborted was something they could never abide. As difficult as this may be to come to grips with, Republicans are on the wrong side politically of an issue that they are clearly on the right side of morally.” Absent in these reactions is any sustained introspection about policy.

This much is obvious with not just Baldwin up for reelection in 2024 but also a presidential race bearing down: “It’s going to be if not the No. 1 state, then top two or three where resources and attention go for the foreseeable future,” said Kanninen.

Still, wariness remains obvious in Wisconsin Democrats’ voices when they consider what comes next. That’s because even with Democrats on the front foot, recent history gives them little reason to rest easy. “I think it’s swinging,” Doyle, the former governor, said of his state, “but I don’t know how long the pendulum is.”