House Republicans can’t do much with their tenuous grip on Congress’s lower chamber. With a Democratic majority in the Senate and Joe Biden in the White House, Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s caucus can’t slash taxes on venture capitalists, purge school libraries of Toni Morrison novels, compel pregnant teens to give birth, or enact any of its other priorities. What the House GOP can do, however, is pick the terrain of partisan battle.

That is no small thing. Different issues favor different parties. On some policy questions, Democrats and Republicans must put the interests of their core constituencies above popular opinion. On others, they are free to pander to the intuitions of the politically fickle Rust Belt residents who will choose the next president. Picking the right fight gets you a long way toward winning it. With its control of the House, the GOP can force votes on any of the myriad subjects that split the Democratic Party internally and unite Republicans with swing voters.

Yet House Republicans have chosen to do the opposite. By effectively threatening to default on the national debt unless Biden slashes the federal deficit, McCarthy and his allies have teed up a fight over America’s fiscal priorities that unites the Democratic Party with the median voter while isolating and fracturing the Republican coalition — a fight that looks likely to dominate Washington over the next weeks and months and to set the tone for the rest of Biden’s first term.

The GOP marched into this battle thoughtlessly, led by demagogues in the conservative media and obsolete instincts. For House Republicans, manufacturing a debt-ceiling crisis under a Democratic president is an act of muscle memory. During the Obama administration, the party repeatedly refused to raise the debt ceiling — the statutory limit on how much money the government can borrow to pay for spending that Congress has already authorized — unless Obama agreed to repeal much of his own legacy. Such brinkmanship was always reckless. Failing to raise the limit would eventually trigger a default on U.S. debt payments and unleash financial chaos around the world. Threatening to sabotage the economy unless the other party does your bidding is no way to govern in a democracy.

Nevertheless, the Obama-era debt-ceiling fights were more coherent than the current one. Back then, the GOP was at least united behind a legible (if draconian) fiscal objective: to balance the federal budget by shrinking spending on virtually everything that couldn’t be used for wars overseas. This time, however, Republicans are more interested in holding the debt limit hostage than in writing a ransom note. The point is evidently to perform their ardor for the Fox News faithful by taking extreme measures, not to produce any particular change in policy. Indeed, McCarthy’s caucus has yet to release a consensus budget proposal. It has radical means but no justifying end. The Speaker and his caucus lack the convictions of their courage.

The reason Republicans have given Biden an ultimatum with no concrete demands is simple: The budget plan that would satisfy every faction in McCarthy’s five-vote majority is mathematically impossible. The caucus’s small-government ideologues want a budget that balances within ten years. Its Trump acolytes want their party to heed the ex-president’s admonition not “to cut a single penny from Medicare or Social Security.” Its defense hawks want the Pentagon’s budget to remain intact. And every Republican believes the country’s historically low top tax rates must be lowered further still. McCarthy’s chief of staff reportedly told a friend recently that these contradictory demands put the Speaker “in a nearly impossible bind.” This is an understatement. To balance the federal budget without raising taxes or cutting entitlements or defense would require slashing discretionary spending on everything else by roughly 85 percent, a prospect even more politically toxic in its implications than Social Security cuts.

Democrats, meanwhile, couldn’t be more comfortable. The party has been winning arguments about the future of Medicare and Social Security for nearly a century. Republicans challenging Democrats to a debate that is, in essence, about whether the U.S. should prioritize entitlement benefits over tax cuts for the rich is a bit like an intramural basketball team challenging the Boston Bruins to a game of hockey.

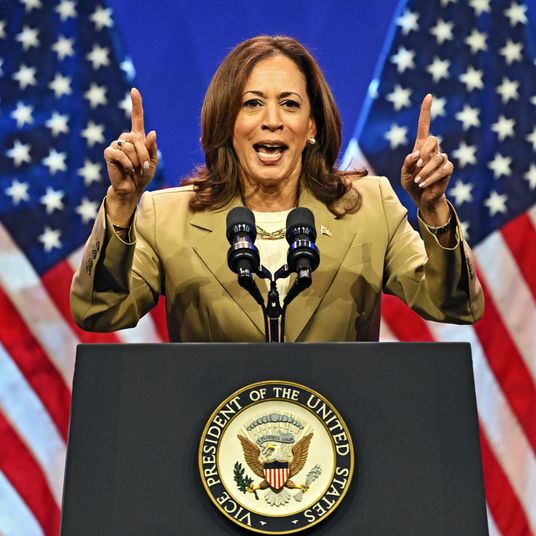

Biden laid out the Democratic position in a New York Times op-ed in March. The president affirmed the fiscal conservatives’ premise that reforms are imminently needed to shore up Medicare’s solvency. But instead of presenting voters with any of the bitter pills that Republican budget resolutions routinely ask Americans to swallow — say, a hike in the retirement age, benefit cuts, or privatization — Biden proposed sustaining Medicare as is and letting rich people and drug companies pick up the tab.

Specifically, the president called for raising the Medicare tax rate on earned and passive income above $400,000 by 1.2 percentage points and expanding the program’s authority to negotiate the price of drugs. It’s hard to overstate the political expediency of this approach. In a 2019 Pew poll, just 8 percent of Americans favored a reduction in spending on Social Security or Medicare, and both programs boasted a net favorability rating of more than 50 points in a recent YouGov survey. In 2021, some 80 percent of voters told Pew they were “bothered” by the fact that “some wealthy people don’t pay their fair share” in taxes. And in the Kaiser Family Foundation’s polling, the idea of strengthening the federal government’s ability to force down drug prices won the support of 83 percent of the electorate.

In other words: Taking from the rich and Big Pharma to give to middle-class retirees is an extremely popular proposition.

Of course, if congressional Democrats actually needed to pass this policy, they might run into problems with their marginal members; some Democrats represent districts where drug companies and McMansion dwellers have a large footprint. But the party doesn’t actually need to confront that problem because Republicans control the House. And the GOP isn’t just structurally incapable of voting for tax hikes on the rich but unable even to claim to support that objective. By contrast, Democrats of virtually every stripe have no compunction about publicly arguing that it is more important to maintain entitlement benefits at current levels than to spare multimillionaires slightly higher tax bills or drug companies slightly lower profit margins.

“Make the rich pay more” is likely the most politically palatable answer to the challenge of deficit reduction. But it is one that no Republican can offer without attracting a fusillade of friendly fire from the conservative donor class. Yet in the post-Trump era, when the Republican coalition is both older and more working class than it was in the Obama years, the GOP cannot comfortably advocate for slashing entitlement spending either. So it has settled for fulminating against the abstract notion of the deficit itself. This stance will be difficult to sustain as the debt ceiling closes in and Republicans are forced to tell the country precisely what they hope to accomplish by threatening economic sabotage. Biden, for his part, can’t wait. The president closed his Times op-ed by imploring his “Republican friends” to put their budget on the table and “show the American people what they value.”

To the extent that the contemporary GOP values anything in the realm of fiscal policy, it is the God-given right of the wealthy to maximize their posttax income. This position puts the party at odds not only with popular opinion but also with many of its own voters. Yet it was the Republican Party that picked this fight. If the debt-ceiling imbroglio ultimately proves politically damaging for the GOP’s House majority, it will die on its chosen hill.

More on the debt ceiling

- It’s Payback Time for the House Far Right

- 2024 Presidential Candidates Side With Far Right on Debt Deal

- Kevin McCarthy Really Did It