For weeks, the Democratic Party’s progressive and right-wing flanks have been locked in a staring contest over spending. The latter contingent is eager to pass the bipartisan infrastructure legislation that passed the Senate in August. The former cares less about that souped-up highway-funding bill than it does about the president’s broader agenda for green investment and welfare-state expansion. And the vehicle for enacting that agenda is the $3.5 trillion “reconciliation” bill — a special type of legislation that is immune from the Senate filibuster and that Democrats can therefore pass without Republican support.

Progressives do not trust their moderate colleagues to toe the party line on reconciliation. Specifically, they believe that once Joe Manchin and friends secure their coveted bipartisan infrastructure legislation, they’ll feel comfortable issuing ultimatums to the left about the reconciliation bill’s size. Which is to say: Having pocketed an anodyne legislative achievement, the moderates will be sufficiently satisfied with their governing record to tell progressives, “You can have $1.5 trillion or nothing” — and mean it.

Thus, to secure some leverage over the centrists, left-wing lawmakers have vowed to oppose the bipartisan infrastructure bill until Biden’s broader agenda is advanced through both houses of Congress. On paper, this is a credible threat. The Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) may not be unified behind the gambit. But it doesn’t need to be. Less than a dozen House Republicans plan to vote for the bipartisan infrastructure bill, according to Politico. On Tuesday night, CPC chair Pramila Jayapal said that more than half of her caucus’s 95 members are prepared to vote against the bipartisan package unless reconciliation is done first.

Nevertheless, the moderate rebels think they can call the left’s bluff. Kyrsten Sinema and a critical mass of House Democrats have reportedly promised to kill any future reconciliation bill — no matter its shape or size — if the House does not pass their bipartisan infrastructure legislation next week. As Jonathan Chait argues, this is (almost certainly) a lie. If the bipartisan infrastructure bill fails next Monday, Sinema won’t stop wanting to pass it. Nor, presumably, will moderates’ preferred level of new social spending drop from $1.5 trillion to $0.

Still, Biden’s disloyal Democratic opposition may hold one genuine trump card. The notion that Sinema & Co. will oppose any reconciliation bill unless the bipartisan one passes next week is silly. But the idea that they would rather see the latter legislation die than support a $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill is more plausible. As Politico reports:

A group of five to 10 House moderates have signaled to leadership that they would be willing to let the infrastructure bill fail rather than be held hostage by liberals over the broader spending bill. It’s a more attractive alternative to them than having to vote for painful tax increases to pay for an unrestrained social safety net expansion, according to a person familiar with the discussions.

Perhaps these lawmakers really would rather see Biden’s entire domestic agenda collapse than abet the passage of a $3.5 trillion spending bill. If this position is credible, however, it’s anything but moderate.

The centrists’ stance rests on one basic premise: that the reconciliation bill is radical in both the scale of its spending and the tax increases it entails. The lawmakers’ avowed preference for undercutting their own party, and forfeiting all of their own objectives for federal spending, is plainly an extremist position, unless one accepts that the $3.5 trillion bill is extraordinary in scope or content.

And yet, by an array of reasonable metrics, Biden’s agenda is neither.

Of course, media coverage of the bill has suggested otherwise. And not without reason: Democrats of all stripes have described the legislation in sweeping terms. For Bernie Sanders, it is “the most consequential piece of legislation for working people, the elderly, the children, the sick and the poor since FDR and the New Deal of the 1930s”; for Joe Manchin, it’s “the largest single spending bill in history.” And all Democrats characterize the bill’s present cost with reference to its price tag over a decade’s time: $3.5 trillion.

The reasons for this aren’t hard to discern. If passed in its current form, the reconciliation package would be the largest expansion of the American welfare state in half a century. Progressives are responsible for that fact and are therefore eager to advertise it. Moderates, for their part, have an incentive to describe the bill in similarly grandiose fashion for the sake of establishing its putative extremity. Meanwhile, in order to initiate the reconciliation process, Democrats had to pass a budget resolution that set a formal ceiling on the final bill’s potential ten-year cost. The number they arrived at was $3.5 trillion. So, it was natural for politicians and the press to start describing the bill using that number.

However reasonable, these descriptive choices have produced a fundamentally misleading discourse. The past year has witnessed the passage of three historically large stimulus bills, which were characterized in headlines as the “$2 trillion coronavirus relief bill,” the “$900 billion COVID-19 relief bill,” and the “$1.9 trillion relief bill,” respectively. In each case, these headlines (roughly) described the legislation’s immediate, single-year fiscal cost. By that metric, the Democrats’ reconciliation package isn’t a $3.5 trillion bill; it’s a $350 billion one.

The fact that news coverage does not dwell on the rather disparate meanings of the price tags it has assigned to the relief bills (which roughly described their single-year impact on the deficit) and the one it is now assigning to the reconciliation bill (which describes its ten-year impact on federal spending, the bulk of which would be offset by tax increases) promotes false impressions about the Biden agenda’s relative cost.

Skeptical readers might scoff at this argument. After all, whatever the reconciliation bill’s single-year cost, it would ultimately increase federal spending by more than than any of the relief bills did. Yet if your objection to Biden’s “$3.5 trillion” bill is that it will drive up inflation — which is to say, if you are Joe Manchin — then the legislation’s immediate fiscal impact is more relevant to your concerns than its ten-year one. This follows from a few simple facts: 1) Inflation occurs when demand for goods and services outstrips their supply; 2) when the government increases spending, it increases demand in the economy; and 3) given sufficient time, however, supply will generally rise to meet demand. For example, if investors notice that government tax credits have driven up consumer demand for electric vehicles, they will direct more capital toward EV production, and the supply of EVs on the market will grow. But expanding production takes time. In the interval between a demand spike and production shift, inflation can arise. Thus, when assessing a bill’s inflationary risk, its lifetime cost is less relevant than the pace of its spending.

By any reasonable measure, the reconciliation bill poses less inflationary risk than the relief bills that Joe Manchin and his fellow “moderates” already voted for, even if one ignores the fact that the reconciliation bill offsets its outlays with tax increases. Spending hundreds of billions on direct relief payments in a single year will rapidly boost demand; gradually increasing federal spending by 5 percent over a decade will not. In fact, much of the reconciliation bill’s spending is likely to be anti-inflationary, as its investments in green infrastructure, innovation, and workforce development promise to increase our economy’s productive capacity, and thus the supply of goods and services available for consumption. Meanwhile, the legislation’s changes to Medicare’s payment rates for pharmaceuticals would directly lower drug prices for America’s seniors (an objective that many of the Democratic Party’s self-styled inflation hawks curiously oppose).

All of which is to say: The reconciliation package is not an extreme or “unrestrained” spending bill as gauged by its implications for inflation. (Not that we should be terribly worried about inflation anyway.)

What about its implications for taxes? Just how “painful” are the leadership’s proposed revisions to the tax code?

Well, the reconciliation bill would raise the corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 26.5 percent. For context, before Donald Trump took office, America’s top corporate rate was roughly 39 percent. In 2012, Mitt Romney campaigned on lowering that rate to 25 percent. So the Democratic leadership’s preferred corporate rate is a hair to the left of a Utah Republican’s and much to the right of the last Democratic president’s.

As for individual income taxes, the reconciliation bill would cut taxes for the roughly 90 percent of American households who earn less than $200,000 a year. It would, however, raise the top income tax rate all the way to … where it was under Barack Obama.

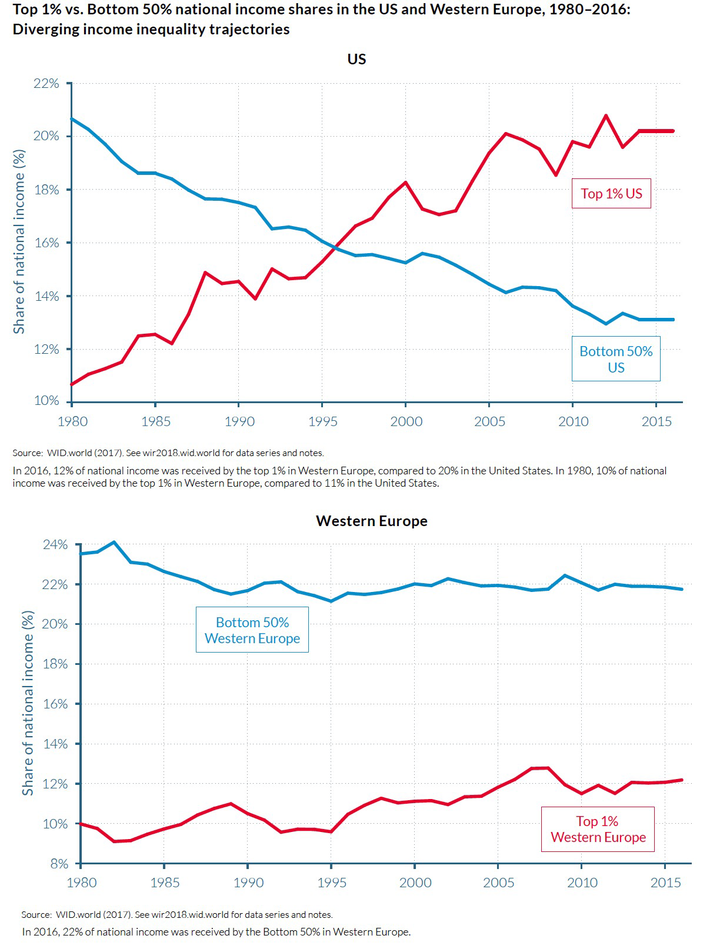

To be sure, the legislation would raise taxes on the superrich substantially, with those earning more than $1 million a year seeing a 10.6 percent increase in their annual tax liabilities. Given that America’s richest one percent command a larger share of national wealth and income than their peers in most other developed countries, however, increasing their taxes doesn’t seem like a terribly radical proposition.

Finally, there are the reconciliation bill’s implications for the American welfare state. Just how “unrestrained” is Joe Biden’s proposed social-safety-net expansion? The reconciliation bill would move the U.S. several steps down the road to social democracy, establishing a monthly child allowance, paid family leave, child-care subsidies, an expansion of public health insurance for middle-income Americans, an extension of at-home care for the elderly, and universal prekindergarten, among other things.

But saying that piece of legislation is the largest expansion of social welfare in the U.S. since Reagan is a bit like saying a canine is the world’s largest toy poodle. Even if Congress passes the Build Back Better agenda in its entirety, America’s safety net will remain more threadbare than those of comparably developed countries. The $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill would guarantee Americans 12 weeks of paid family leave; the OECD average is 18 weeks. Biden’s child allowance would be a landmark achievement for the U.S. But such child benefits have long been standard in Canada and Western Europe. And the reconciliation bill’s version of the child allowance isn’t even permanent — it actually expires after 2025. Prekindergarten is a similar story. Thanks to their relatively higher levels of investment in early-childhood education, the average preschool-enrollment rate among 3-year olds in OECD countries was 70 percent in 2017; in the U.S., that figure was 40 percent.

When House progressives say, “$3.5 trillion was the compromise,” they’re being both serious and reasonable. Thanks to Senate moderates’ filibuster fetish, this reconciliation bill is poised to be the last piece of major legislation passed in Joe Biden’s first two years in office. And since the GOP’s odds of retaking the House in 2023 are very high, the reconciliation bill could very likely be the only major partisan law that Democratic voters get out of the Biden presidency. It could be a long time before Democrats boast a federal trifecta again. Progressives have nevertheless agreed to settle for a bill that increases federal spending by only 5 percent over a decade, leaves most of Donald Trump’s corporate tax cut intact, and keeps the American welfare state stingier than those of its less-wealthy peer nations.

And Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema consider this offer such an insult to their values and priorities they’d rather make Biden a failed president than attach their names to it.

With moderates like these, who needs reactionaries?