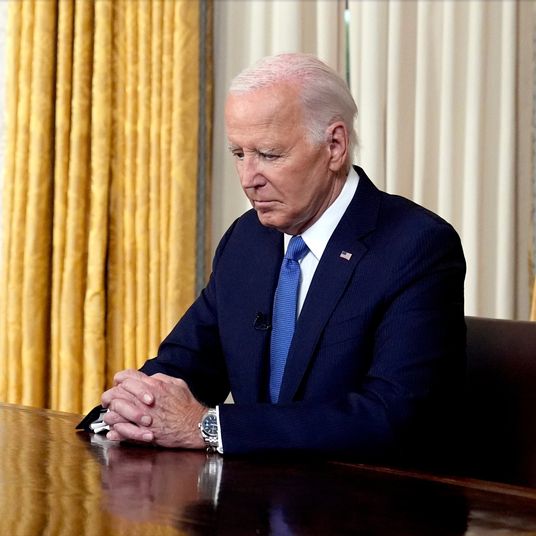

We are nearly two months into Joe Biden’s presidency, and observers unsurprisingly differ on how well he is doing. Even critics have to admire his speedy success in passing a $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief and stimulus package that could not have survived the smallest of Democratic defections. Some Republicans and fans of bipartisanship as an end in itself think the 46th president has bought a world of future trouble with that bill by poisoning the well for others. The small but noisy band of old-school fiscal hawks are sure the stimulus bill will bring the often-predicted return of inflation as an economic problem, along with a revival of austerity politics. And some Democrats are fretting that Biden won’t be as bold in future initiatives (i.e., those not achievable via filibuster-proof budget reconciliation bills) as he was with his first.

Is there some more objective way of adjudging presidential success, particularly early in an administration? Traditionally considerable weight has been placed on presidential job approval ratings, which if nothing else, measure whether a president is building the political capital to sustain success, ideally via reelection and then a shot at Mount Rushmore. But as we all understand now, partisan polarization has flattened public sentiment towards presidents, lowering the ceiling and lifting the floor for “successful” and “failed” chief executives alike. So it means little that Biden’s initial job approval ratings are lower than those of virtually all of his predecessors other than the man he beat. They are actually pretty close at present to those of both Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, who wound up having very different first-term trajectories.

Indeed, a look at how the 42nd, 43rd, 44th and 45th presidents performed in the first two years is instructive in showing the wide range of directions the Biden presidency could take.

Bill Clinton: a Rocky Beginning Down a Slippery Slope

Clinton inherited a slowly improving but still sluggish economy and a Democratic-controlled Congress. But he stumbled early on with appointments (famously taking three times to find an attorney general who could make it past confirmation hearings); and then fell into Republican traps on stimulus measures that were too easily caricatured as pork (at one point the administration asked state and local governments for wish-lists of projects that could be quickly completed, serving up ripe targets for negative ads. Clinton struggled but eventually succeeded in passing his first budget, which included relatively unpopular tax increases and energy charges, though not until August of 1993. But then he was drawn into two big first-year fights over trade policy (NAFTA and GATT) that split Democrats and alienated labor, winning congressional approval only with Republican votes.

A big part of Clinton’s second year in office was devoted to efforts to enact a health care reform plan that was both complicated and controversial, often called “HillaryCare” because of the First Lady’s prominent role in the process. Its failure cast a pall over the 1994 midterm elections, which delivered both Houses of Congress to the Republicans for the first time in four decades, as Clinton’s own job approval ratings dropped into the 40s and occasionally the 30s.

Clinton was conspicuously more successful in digging his way out of this hole and using the hubris of Newt Gingrich’s “Republican Revolution” in Congress to outmaneuver his opponents in budget negotiations. After beating back GOP efforts to gut domestic government and then signing a then-popular welfare reform bill, Clinton positioned himself to win a relatively easy reelection. The remainder of his presidency was known for a disconnect between his personal problems (culminating in the Lewinsky scandal, an impeachment in the House, and acquittal in the Senate) and the popularity of his policies, which were given credit for a nearly unprecedented economic boom (which was thrown into some disarray by a slump in tech stocks in 1999).

George W. Bush: A Good Start and Then the Unimaginable

Inheriting a federal budget surplus, Bush made his first big speech to the nation near the end of February of 2001 framing his demands for a major tax cut (on which he had campaigned) as a matter of “asking for a rebate” on behalf of overcharged taxpayers. He succeeded in enacting a package of individual tax cuts in July of 2001 (enacting big cuts in business taxes and extension of the 2001 cuts in 2003). By the beginning of 2002, Bush had also implemented another big campaign pledge with enactment of the No Child Left Behind education reform bill. But in the meantime, of course, everything had changed with the September 11 attacks, U.S. retaliation against the Taliban regime of Afghanistan, and initiation of what was universally known as a Global War on Terror. Bush’s approval ratings leapt from 51 percent to 90 percent in the days immediately following 9/11, and remained well over 60 percent at the time of the 2002 midterms, in which Republicans made gains (the first time the party controlling the White House had done that in a president’s first midterm since FDR).

Bush quickly expended his popularity launching war with Iraq in 2003, and eking out a narrow reelection win in 2004; that year he also won his last major legislative victory with enactment of a Medicare prescription drug benefit (bitterly opposed by many conservatives). His second term exhibited a slow bleeding of public support. An initial effort to enact partial privatization of Social Security benefits failed completely. As the occupation of Iraq dragged on and grew more unpopular, paired with the administration’s inept handling of Hurricane Katrina, Bush’s job approval rating steadily declined, hitting 36 percent in May of 2006. Democrats regained control of Congress that year, and the second Bush administration seemed helpless to deal with the housing and financial crises that occurred shortly before his presidency ended.

Barack Obama: Costly Triumph, Gradual Recovery

Obama took office with the highest initial approval ratings of any president since Jimmy Carter 32 years earlier, and with comfortable Democratic margins in both Houses of Congress. And he got his own economic stimulus package enacted more speedily than has Biden, signing it on February 17, 2009. But he had to make major concessions to get the one Republican vote to overcome a GOP filibuster in the Senate, and lost a lot of time vainly pursuing Republican support for his signature health care reform legislation. After a shocking GOP victory in a Massachusetts special election for the late Ted Kennedy’s Senate seat, Democrats had to resort to budget reconciliation to put the finishing touches on Obamacare, which was finally signed into law on March 23, 2010. For a variety of reasons, including the slowly recovery economy, the complexity of Obamacare, and over-exposure of Democrats after two consecutive big congressional victories, Republicans won a huge top-to-bottom landslide in 2010.

Much like Clinton after the 1994 defeat, Obama succeeded in exposing Republican extremism and benefitted from an economy that was growing just enough to win him a second term over a vulnerable GOP opponent. But his party lost the Senate in 2014 and the 44th president was unable to turn over the White House to his chosen successor.

Trump: Presidential Carnage From the Get-Go

The 45th president entered office with an underwater approval rating, an angry and divisive Inaugural Address, zero efforts to reach out beyond his party, and at best shaky efforts to work with his own party, which controlled Congress. His signature initial moves were to begin building a border wall and to ban entry of Muslims – unpopular and legally dubious efforts that appealed mostly to his nativist base. His first big legislative push was a rigorously conservative budget reconciliation bill that controversially aimed at repeal and replacement of Obamacare. But under his erratic leadership the legislation twice failed in the Senate. Late in 2017 he and congressional Republicans finally enacted a package of tax cuts that wasn’t particularly popular, but for a long time that was Trump’s only legislative trophy. Wrangling with leaders of both parties and widely spreading investigations consumed much of 2018, which concluded with the narrow confirmation of a controversial Supreme Court Justice, large midterm Democratic gains, a government shutdown mostly caused by Trump’s border wall demands, and then more investigations. By the end of 2019, Trump had been impeached by the House for encouraging Ukraine’s government to make damaging allegations against Joe Biden.

2020 began with Trump’s acquittal by the Senate, soon followed by his inept initial handling of COVID-19 and many ensuing months of uneven presidential leadership and attacks on liberalized voting accommodations being made by the states. Throughout it all Trump’s job approval rating was largely static and consistently underwater. He and his party did better in November 2020 than most observers expected, but his decision to contest the results into the new year, punctuated by his involvement in the January 6 Capitol Riot, earned him a second, post-presidential impeachment, and a second Senate acquittal. His job approval rating finally plunged into the low 30s as he left office, leaving him with an average rating of 41 percent from Gallup, the lowest of any president since World War II.

A Low Bar For Biden

The 46th president’s initial trajectory resembles that of the 43rd: a quick legislative win benefiting from party unity that redeemed a central campaign pledge, and a demonstration of some legislative and public opinion skills. Biden will not likely enjoy the sort of insane public approval spike 9/11 gave George W. Bush, which in turn led to a rare pro-presidential midterm. And at his age he may not choose to fight for the second term that Bush so notably squandered. If his own legacy matters to him, Biden would be well advised to go for the gold and secure as much as he can as quickly as he can from Congress. The odds are very high that a record of getting important legislation enacted is a better route to relatively high popularity than any effort to strike grand bargains with Republicans. Barring some dire developments in the objective conditions of the country, Democrats are unlikely to suffer the massive midterm losses they experienced in 1994 or 2010. And so far their relative unity as compared to the Trump-haunted opposition is a good sign for 2024, particularly if there is not a savage competition for the Democratic presidential nomination then.

If Biden rolls the dice and pursues filibuster reform to enable a broader and more profound set of legislative achievements, thereby enraging Republicans and a segment of the mainstream media, he could either soar high or fall low, or do both in succession. But you cannot fault him for his quick start and from fully exploiting a relieved atmosphere of freedom from the hourly trauma of the Trump presidency.