WATERLOO, Iowa — Having spent more than half her life in Waterloo, Iowa, she has built a life here. It’s where she met her husband and where her only daughter, who wants to become a sonographer, was born.

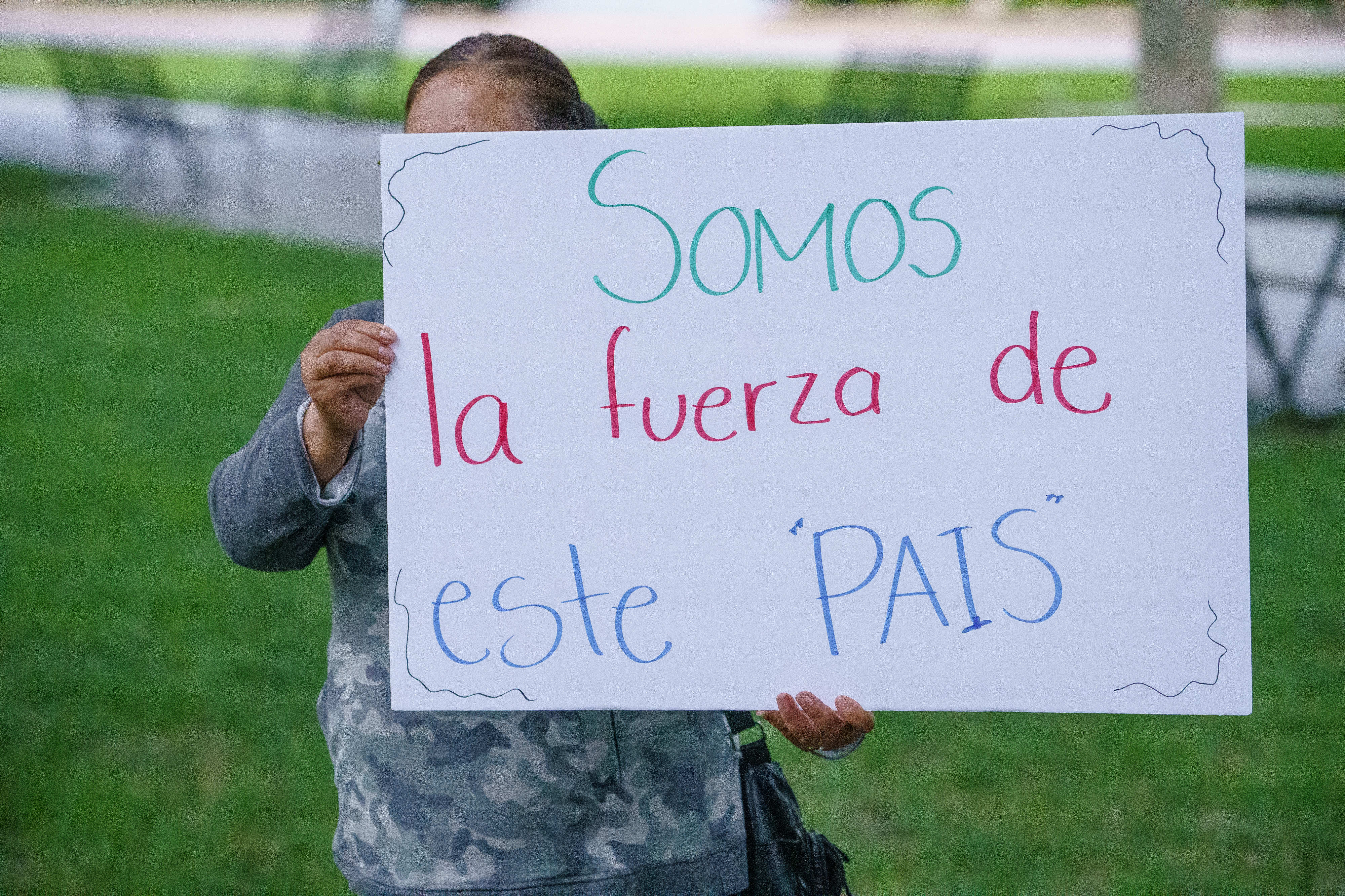

That’s why, after a day’s work at an area meatpacking plant, the 55-year-old Mexican-born woman took to Waterloo’s streets Monday. Waving a banner reading in Spanish, “We are the strength of this country,” she protested a new state law that could severely impact her family, she said.

The law, which a federal judge temporarily blocked recently as it is contested in court, would allow Iowa law enforcement to arrest individuals even if they have legal permission to remain in the country. While the woman herself would not be directly affected by the law, her husband could be. He’s an undocumented immigrant who was previously deported and re-entered the country.

She and hundreds of other immigrants took to the streets July 1 in Waterloo, Des Moines and Iowa City to protest the new law. Without the judge’s intervention, it would have gone into effect that day.

“We are here with that insecurity. We have considered returning to Mexico, even though it would mean truncating all our dreams for our daughter. It’s a hard decision to even think about and even harder to make,” the woman said in Spanish. She asked Investigate Midwest not to reveal her name or employer over concerns for her family’s safety.

Other immigrant workers also are torn between remaining or leaving the state to avoid their own potential deportation or the deportation of their undocumented family members, according to interviews Investigate Midwest conducted with migrant advocacy groups and 10 immigrant families living in Iowa. Most family members requested anonymity over fears their loved ones could be deported if they were identified.

If immigrants leave in large numbers, the economy of this agricultural state, already in need of more labor, could be jeopardized, advocates said.

“Here in Iowa, the immigrant community plays a very important role in agriculture, construction and service sector health care,” said Joe Henry, state political director of the League of United Latin American Citizens, or LULAC, a 95-year-old civil rights organization. “This would really cause chaos in a lot of different industries economically, if this law were to go into effect. It’s not just the families but also the economy.”

In a press release following the law’s injunction, Gov. Kim Reynolds said the Biden administration is failing to enforce federal immigration laws, allowing millions to enter and re-enter the country without any consequences or delays.

“I signed this bill into law to protect Iowans and our communities from the repercussions of this border crisis: rising crime, overdose deaths, and human trafficking,” she said.

The agricultural industry’s operations in the country are predominantly dependent on immigrant labor, including undocumented labor. According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey, nearly 7 in 10 agricultural workers were born outside the United States. Most of these workers are of Mexican origin. More than 40% have no authorization to work in the U.S., and 1% have work authorization through another status.

Iowa, with a population of about 3 million people, is home to as many as 75,000 unauthorized immigrants, according to the most recent estimates by Pew Research Center.

Many immigrants work in concentrated animal feeding operations, meatpacking plants and in corn fields. Iowa produces more corn than any other state, and it exports — by far — more pork than any other state.

In Waterloo, a rural city with just under 67,000 residents, 7% of whom are Latino, the main industries include John Deere — one of the leading U.S. manufacturers of agricultural machinery — and Tyson, the world’s second-largest processor and marketer of poultry, beef and pork products.

John Deere; Tyson Foods, which has several meat processing plants in Iowa; JBS, another major meat processor with plants in Iowa; the Iowa Farm Bureau; and the Iowa Corn Growers Association did not respond to requests for comment.

read more on agriculture and immigration

The new law could put a lot of pressure on undocumented workers and their families, said Ninoska Campos, a workers’ rights activist in Iowa City.

“Cops don’t know if people have documents, and this law allows someone to be stopped based on their appearance,” she said. “That puts undocumented people at risk.”

An election year

Just two weeks before it was set to take effect, a federal judge temporarily blocked Iowa from enforcing its new immigration law, which criminalizes entering Iowa after being deported or denied entry into the United States. If an undocumented person is found, they would be deported under the law.

This judicial intervention followed a challenge by the U.S. Department of Justice, the American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa, the national ACLU, and the American Immigration Council, acting on behalf of the Iowa Immigrant Justice Movement and two Iowa residents.

“Iowa cannot disregard the U.S. Constitution and settled Supreme Court precedent,” Brian M. Boynton, principal deputy assistant attorney general and head of the Justice Department’s Civil Division, said in a statement. “We have brought this action to ensure that Iowa adheres to the framework adopted by Congress and the Constitution for regulation of immigration.”

The Iowa law was set to take effect on July 1, during an election year marked by widespread Republican criticism of the Biden administration’s handling of immigration issues.

Republicans in Congress blocked a bipartisan agreement with Senate Democrats and Republicans that would have brought significant reforms to America’s immigration laws. These reforms included adding essential border and immigration personnel, investing in technology to detect illegal fentanyl, overhauling the asylum system and granting the president emergency authority to close the border when the system is overwhelmed.

Iowa’s new immigration law also follows in the footsteps of similar legislation enacted in Texas by Republican Gov. Greg Abbott this year. Oklahoma and Arizona have also passed similar laws this year.

Timi Brown-Powers, a Democrat member of the Iowa House of Representatives who participated in the protest Monday, said the governor’s support of the impending law was “all political.”

“This is the governor’s way to come out to say that she is tough on immigration,” she said. “This immigration bill was her big push to say that she does not stand for immigration, and she’s going to minimize it in Iowa.”

When asked for comment on that criticism and on families considering leaving the state, Kollin Crompton, the governor’s deputy communications director, pointed Investigate Midwest to previous comments Gov. Reynolds made about the Biden administration.

The law has also faced criticism from several Iowa sheriffs, who believe immigration enforcement falls outside their purview and that they lack the resources to effectively implement the law.

Black Hawk County Sheriff Tony Thompson expressed concerns about the enforceability of the new law, noting the absence of accessible records on individuals’ deportation histories.

“Emulating someone else’s problem here in the center of the heartland is a far different cry than emulating somebody’s problem right there on the border,” Thompson told CBS 2 Iowa, a local TV station, in May.

He further explained the logistical difficulties: “This is federal record — ICE information, border patrol information. So all of that is well-intentioned, but the challenge for us is, if it doesn’t exist, we can’t create the record.”

Living in fear

Father Nils Hernandez, pastor of Queen of Peace Parish where the protest began Monday, said the new immigration law keeps the immigrant community in a state of fear.

Hernandez, who also directs the Waterloo Catholic Hispanic Ministry, said he told community members weighing whether to leave the state not to rush their decision. “You don’t have to make a quick decision. Wait and see how things develop. Don’t make decisions quickly,” he said he cautioned them.

The Catholic priest, who once was an undocumented immigrant, fled the war plaguing Nicaragua in the 1980s and entered the country by crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. On his journey to the U.S., he was deported from Mexico to Guatemala.

He advocates for new immigration reform to create a pathway that offers stability for those living in the shadows, burdened with the stigma of being undocumented.

Hernandez said the federal judge’s temporary block on the law impacts the stability of mixed-status families, where U.S. citizens live alongside those who lack legal permission to be in the country.

Families interviewed by Investigate Midwest said that their greatest fear is family separation, a significant concern in Latino cultures where extended families — including children, aunts, uncles and grandparents — value living in close geographic proximity.

Family members said Colorado, Illinois, Minnesota, Oregon, Washington, and Kansas were potential destinations to protect them from being separated through deportation.

Fidel Silva, 49, is another immigrant who would not be directly impacted by the law, but he worries about his youngest child and his brother, neither of them have immigration documents. Silva arrived in the U.S. in 1990 and now works at a factory producing boxes in Waterloo that supplies material for meatpacking plants.

“My fear is that one wrong move could jeopardize our little one,” he said.

He is now seeking “sanctuary cities” where he can work with peace of mind and potentially obtain a driver’s license.

Angelica Rodriguez, 40, who came to the United States as a teenager, also participated in the march to protest the new immigration law. Despite being protected under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals — a policy that provides temporary relief to some undocumented immigrants brought to the country as minors — she fears being detained by authorities on the street. As a single mother who has lived in Iowa for 10 years, her primary concern is the possibility of being separated from her four children.

Both Silva and Rodriguez gave permission for Investigate Midwest to use their names.

For the meatpacking worker who carried the “We are the strength of this country” banner, she already lives with anxiety. When her husband comes home later than usual from his shift at a Mexican restaurant, she starts to fear the worst.

“He used to close the restaurant with his colleagues, and sometimes clients arrive at the last minute,” she said. “When it’s past the time he normally arrives, I start fearing that the police have arrested him.”

Comments are closed.