By Rikhil Bhavnani and Saumitra Jha

This is a story of a quest for new data, and an attempt to fill in a key gap in our understanding of one of the most important nonviolent movements in world history.

The “Quit India” struggle of 1942 was Mohandas Gandhi’s third and last great nonviolent movement aimed at achieving democracy and independence for Indians from the British Empire. In post-Independence Indian texts, it is often referred to as the August Kranti—the August Revolution, a moment of heroism, with many a grandparent claiming to be an overt or covert participant. For the British government, it was a seditious rebellion that led them to temporarily lose control of a number of districts, and required the use of eight British brigades and fifty-seven Indian battalions to suppress. Royal Air Force fighters were used to machine-gun crowds from the air.[i] And, as we will show, despite the smiling faces of stalwart crowds depicted in murals such as that above, the violence was not only on the British side.

Thirteen years ago, we set out to see if we could bring the tools of quantitative social science history and political economy to shed new light on India’s struggle for democratic freedoms and the lessons we could learn from its successes and failures for helping nonviolent approaches to be more effective in affecting socially beneficial change today.

As we discuss in our book project, and its companion research papers[ii], the central challenge for many nonviolent movements is how to grow, attract attention and apply political pressure while still staying disciplined and nonviolent. A key puzzle we wanted to understand was how the Indian independence movement was able to maintain a largely nonviolent mass movement in favour of democratic governance that encompassed both rich and poor, and much of India’s remarkable ethnic and geographic diversity, despite having the odds stacked against it. In the 1930s, for example, amidst a global Depression that left India badly hit, the Congress successfully launched and maintained a largely non-violent movement for close to three years (see Figure 2). We argue and provide evidence that the Congress was able to leverage the economic shock of the Great Depression to adopt a platform of economic justice. This broadly appealing platform helped them to forge a mass movement, even while a cohort of leaders, screened specifically for their commitment to nonviolence, helped keep the movement peaceful. The Civil Disobedience movement of the 1930s, which began with a declaration of Independence on January 26, 1930 and included Gandhi’s famous “Salt March” that April, was successful in pressuring the British government and paved the way to the 1937 elections, the first in which a significant share of the Indian population gained the right to vote.

Yet the Civil Disobedience Movement of the 1930s, though remarkably successful, was only the second of Gandhi’s three great mobilizations, and was the only one to achieve significant policy concessions. Rather than ignore the others, in our book, we argue that the movement’s failures are as illuminating as its successes. And the last attempt at mass mobilization—that of the Quit India Struggle of 1942—was arguably an abject failure. It clearly failed in its proximate objective of accelerating Indian independence. It also failed as a nonviolent movement. Unlike the civil disobedience movement of the 1930s, that was sustained over the course of years, the Quit India struggle became largely a violent insurrection within a matter of days and violently was it repressed (Figure 3).

This may be because the data has been very hard to come by. The war-time British government engaged in active propaganda and imposed heavy censorship within India, seeking to keep the details of the movement from their own people back home and their allies as well. As the Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow, cabled Winston Churchill on August 30, 1942: “I am engaged here in meeting by far the most serious rebellion since that of 1857, the gravity and the extent of which we have so far concealed from the world for reasons of military security.”[iv] And despite a number of valuable, mostly qualitative accounts of the movement from specific provinces, a full quantitative picture of the extent of the struggle across the subcontinent, the ferocity of the violence that occurred, and the lessons we can learn for other nonviolent movements, has been hard to find, until now.The common, arguably dominant, narrative of India’s Independence movement is one of learning by doing, success building upon success, culminating with Jawaharlal Nehru’s famous “tryst with destiny”, as India attained independence in 1947. But the Quit India Struggle does not fit well with that story. For example, the Oscar-winning movie Gandhi, despite its generous length of three hours and ten minutes, skips over the 1942 movement entirely. Influential recent academic overviews of civil resistance, when they do mention Quit India, also present very positive perspectives of its nonviolent nature, though without referencing data.[iii]

So why did the highly organized Indian Independence movement fail in 1942, despite having achieved success in the 1930s? We argue that to understand this, one need to understand the crucial role of hierarchies and leadership in maintaining the nonviolent discipline of the movement. This had proven very fruitful in sustaining a multi-year movement in the 1930s. But hierarchies can also create vulnerabilities, particularly if regimes are willing to take the extraordinary measures the British colonial authorities were willing to do during the War. But to show this, we first needed to find a file that had proven elusive for more than half a century.

As early as 1940, British officials in each province began assembling two lists, “A” (tellingly referred to as ADOLF) and “B” (BENITO), respectively, in anticipation of an upcoming mass movement. The aim was to decapitate the movement and prevent it from gaining the traction it did in the 1930s by arresting the most capable Congress leaders as early as possible, in one synchronized action.[v]

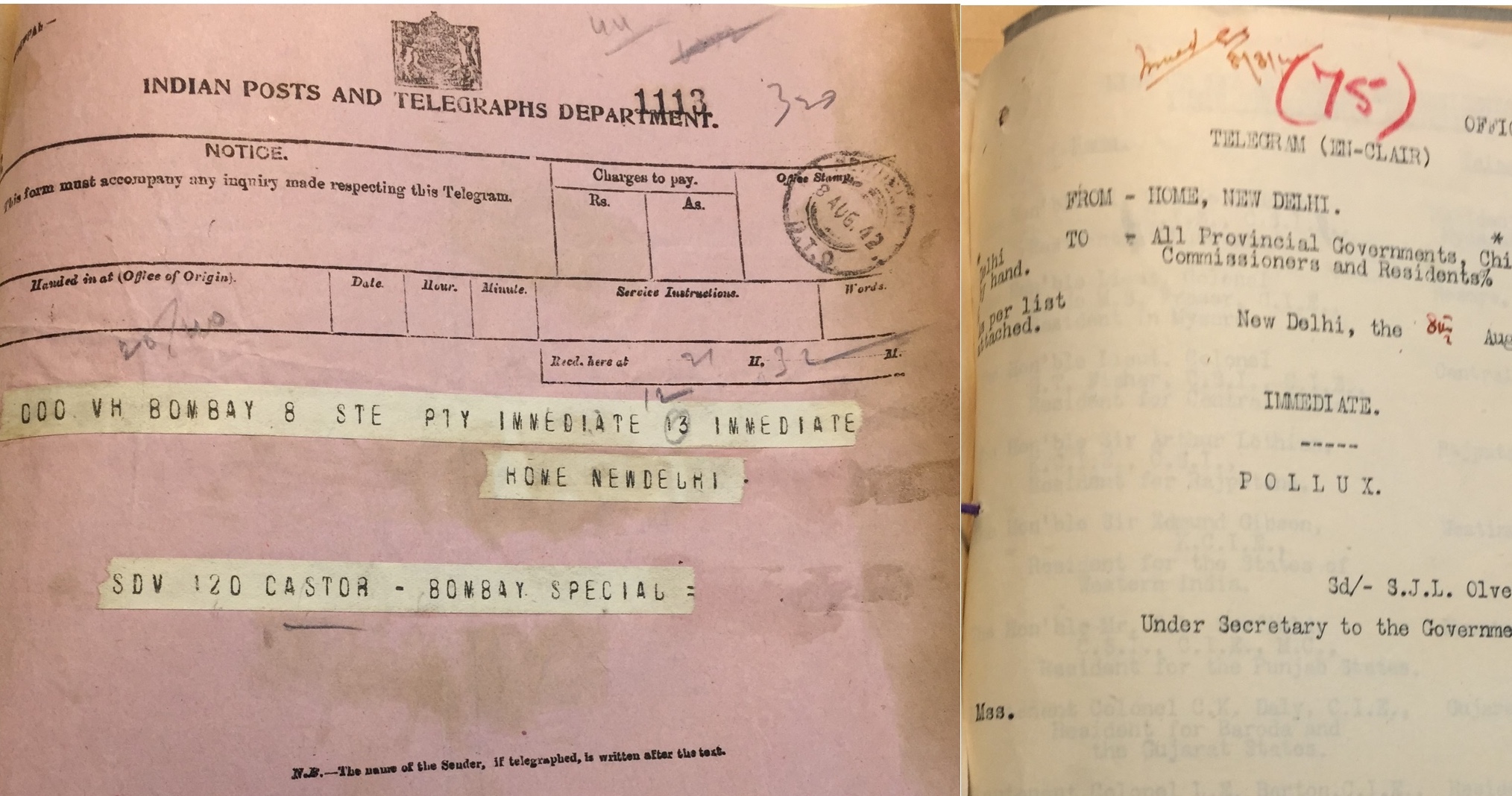

At its meeting in Bombay on the 8th August 1942, Congress was expected to formally launch its newest nonviolent mass mobilization to induce Britain to “Quit India”. If this happened, the local authorities in Bombay were to dispatch a telegram with the codeword “CASTOR”, warning all other governors to make ready. If they then received an answering telegram from Delhi with the twin codeword, “POLLUX”, they were to immediately begin the mass arrests of all those on the A List (see Figure 4).

After Independence, many in India claimed to be freedom fighters during the Quit India struggle, with not only much honour, status and influence, but also pensions on the line. The A and B Lists promised instead to provide a unique contemporary source of everyone in the movement that the British government itself considered to be the most imbued with the capacity for leadership and organization, and specifically those the British most wanted to track down and arrest in those dark early hours of August 9, 1942.

Having found mention of the file, both of us searched, fruitlessly, for the A and B lists of names for many years in archives in both India and the United Kingdom. We got close at the National Archives in Delhi. There, Saum was told the file was being reshelved and would remain so until he had to leave. Months later, Rikhil visited, only to be told that the file was checked out to Saum. And so it went on. Finally, we asked for the help of our secret weapon: Saum’s mother, Pratima.

Pratima Jha, of course, ranks with Mala Bhavnani as one of the world’s best mothers, from the objective and unbiased standpoint of the authors of this piece. Also like Mala, and crucially for this story, she is a people person. Within days of going to the National Archives in New Delhi, she found a helpful archivist, Dinesh, and with his assistance, discovered that the reference we were hunting for was a very thin and disappointing 1942 revision with only about 20 names. But wedged on a small slip of paper, Pratima found a reference to an earlier 1940 list. And this, at last, proved to be the fat file, detailing more than 1500 individuals, one that belonged to a set that hardly been accessed, if at all, for close to half a century (see Figure 5). Our deepest thanks to our moms (and Dinesh)! One key lesson we have learned from this is do not leave your star talent on the bench.

The file has proven to be a trove of data that we are still in the process of exploring for our book. In some provinces, such as Madras, local officials go into considerable detail explaining why, in their opinion, each leader should be on the list and what are the factors that make them more or less likely to become a significant organizational threat. For example, we learn that Mr. S.A. Daivanayagiah of Chidambaram, once a redoubtable organizer, is seen by the local intelligence officers as less excited about the prospect of going to jail for nonviolent civil disobedience after having recently gotten married.

The A-List file, accompanying internal documents and the empirical evidence also make clear that the British, despite later attempts to blame the Congress for the violence of 1942, were more concerned with the organizers of nonviolent resistance when making the list. For example, the size of the blue circles in Figure 6 show the number of A-List leaders selected from each district, underlain by the extent to which there was violent (Left) and nonviolent (Right) mobilization in the 1930s. While as the figure suggests, the number of A-List leaders in a district is correlated with both forms of mobilization, the relationship between nonviolent mobilization in the Civil Disobedience Movement and the A-List is much stronger, and in fact, controlling for it renders the relationship with violent mobilization insignificant.

Yet, as we discuss in our book, by arresting those leaders most committed to nonviolence, the British government, while hoping to stop the movement in its track and prevent it from gaining momentum, instead unleashed the wave of violence that became the August Kranti. As Figure 7 shows, districts that had leaders on the A-List went from being predominantly nonviolent in 1930s movement to turning violent in the 1942, not long after those leaders were arrested. This would lead to the arrests of more than 91,969 individuals, with more than 301 separate incidents of police firings and thousands shot by the end of 1943.[vi]

South Asia would never be the same. The key nonviolent leaders of the Congress would spend the rest of the war in jail, leaving a political vacuum to be filled by others less committed to nonviolence and a politically united subcontinent. While the success of the Civil Disobedience Movement arguably set India on a path to independence, the Quit India Struggle did the same for its Partition. Yet, we argue too, that India’s nonviolent movement, based as it was on leaders who required the consent of the many, also laid the foundation, at least for some generations, of one of the world’s most unlikely democracies.

[i] As the Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow wrote to the Secretary of State for India in London: “If you have any trouble in the debate [in Parliament] about shooting from air, it may be worthwhile mentioning that in many cases this action was taken against mobs engaged in tearing up lines on vital strategic railways in areas which ground-floor forces could not reach… But this is not true of all cases in which firing occurred from aircraft…”, Viceroy to Secretary of State (4 October 1942).

[ii] See Rikhil Bhavnani and Saumitra Jha (2014) “Gandhi’s Gift: Lessons for Peaceful Reform from India’s Struggle for Democracy”, Economics of Peace and Security Journal, Rikhil Bhavnani and Saumitra Jha “Forging a Nonviolent Mass Movement: Economic Shocks and Organizational Innovations in India’s Struggle for Democracy”, Stanford and Wisconsin working paper, and Rikhil Bhavnani and Saumitra Jha “Freedom Struggles and Ethnic Conflict: Evidence from South Asia“, in progress, and our book project, (working title) Walking Together and Alone: Why Nonviolent Protests Fail and How to Make them Work.

[iii] For example, Sharon Nepstadt’s otherwise very valuable overview, Nonviolent Struggle, devotes a single paragraph, reproduced here:

The Quit India campaign[,] began with an inaugural speech whereby Gandhi warned that “We shall either free India or die in the attempt; we will not live to see the perpetration of our slavery.” Shortly after his speech, Gandhi and other National Congress leaders were imprisoned, but civil resistance continued unabated. Although the British government had banned protest marches, satyagrahis held major demonstrations, processions, and general strikes. … The arrests did not weaken the movement: civil resisters persisted, nonviolently raiding municipal government facilities and developing local parallel government institutions.” (56)

[iv] Viceroy to Prime Minister, 31 August 1942

[v] As a “most secret” telegram dispatched to provincial governors on 3rd August 1942 describes, the aim was to: “arrest … all individuals whom [you] consider competent and likely to attempt to organize and launch [a] mass movement. No individual will be arrested merely as a member of [an] unlawful association[. The] general object being not to fill the jails but to limit the number of arrests to those regarded as essential for dislocation of the Congress organization.’’

[vi] See Home Department History of the Congress Rebellion, IOR R.3.1.348, Appendix VII, marked “Most Secret”.