Background

Background

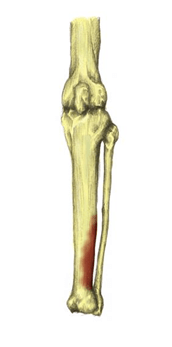

Your shin bone (tibia) is the bone at the front of your lower leg that runs from your knee to your ankle.

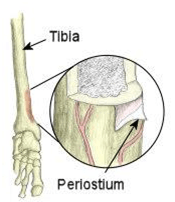

Shin splint’s is a general term used to describe any condition that causes pain down the middle, or on either side of your shin. Exercise-induced pain usually manifests itself in the front aspect of the lower legs. The medical name for this is medial tibial stress syndrome. The underlying problem is inflammation of the outer covering of the bone (periosteum).

Depending on the type of injury you have, the pain may come on gradually or you may have a sudden twinge of pain. Shin splints usually develop in people who do repetitive activities and sports – either during or after strenuous activity – that put a lot of stress on the lower legs, such as running, dancing, aerobics, gymnastics, football and hockey; i.e. sports with sudden stops and starts. Some soldiers also complain of shin splints during loaded marches.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of shin splints include:

- Tenderness along the front, or inside, of the lower leg;

- Aching or sharp pain along the front, or inside, of the lower leg;

- Pain at the start of exercise which often eases as the session continues;

- Pain often returns after activity and may be at its worse the next morning;

- Sometimes some swelling;

- Lumps and bumps may be felt when feeling the inside of the shin bone;

- Pain when the toes or foot are bent downwards; and/or

- Redness over the inside of the shin (not always present).

The pain is often worse when you do activities that involve supporting your body weight. You may feel pain along the whole length of your shin, or only along a small section.

The pain may build up during exercise and it will become more severe the longer you exercise, and if you ignore it and continue exercising it can become extremely painful and force you to stop sport altogether.

The pain may build up during exercise and it will become more severe the longer you exercise, and if you ignore it and continue exercising it can become extremely painful and force you to stop sport altogether.

It is really important not to ‘run through the pain’, as the shin pain is a sign of injury to the bone and surrounding tissues in your leg. Continued force on the legs will make the injury and your pain worse.

Instead, you should rest and take a break from the sport for at least two weeks. You can still exercise during this time off, but choose activities that will not put too much force on your shins, such as cycling or swimming.

Causes & Risk Factors

Shin splints can be caused by a number of factors which are mainly biomechanical (abnormal movement patterns) and errors in training. Here are the most common causes:

- Overpronation of the feet (rolling feet inwards);

- Oversupination of the feet (rolling feet outwards);

- Inadequate footwear;

- Increasing training too quickly;

- Running on hard surfaces;

- Decreased flexibility at the ankle joint;

- Stress fractures: these are an overuse injury. They develop after repeated periods of stress on your bones; for example, running or dancing over a long period of time; and

- Compartment syndrome: this happens when your muscle swells. Your muscle is within a close compartment and so does not have much room to expand. When the pressure in your muscle increases it causes the symptoms of compartment syndrome.

All of these conditions can develop when you put too much stress and strain on your shin bone. This happens when there is repetitive impact on your shin bone during weight-bearing sports or activities. You are more at risk of developing shin splints if:

- You increase your running distance;

- You are an inexperienced runner;

- Your sport or activity involves running or jumping on a hard surface;

- You do a lot of hill running;

- You increase your frequency of running and do not allow a rest day between runs;

- Your shoes do not fit well or do not have enough cushioning and support;

- You are overweight, as this places extra weight on your legs;

- You have weak ankles or a tight Achilles tendon (band of tissue connecting the heel bone to the calf muscle);

- You have flat feet or your feet roll inwards (pronate), as this places more pressure on the lower leg;

- You change your running pattern and the surface that you run on; for example, going from running on a treadmill to running on the road; and/or

- You participate in loaded marches, especially when unconditioned.

Rest and Recovery

You should rest your injury and think about what may have caused your shin splints.

You should be able to recover fully from shin splints if you rest for at least two weeks. This means you should not do any running or ‘stop and start’ sports during this time, although walking, swimming and cycling are OK.

Pain and any swelling can be relieved by raising your leg and holding an ice pack to your shin (try a bag of frozen peas wrapped in a tea towel). Do this for 10 minutes every few hours for the first two days. However, you should also consider the treatment options outlined below.

Treatment Options

Treatment for shin splints involves identifying training and biomechanical problems which may have caused the injury initially. Rest to allow muscles to return to their original condition and gradually return to training.

Self-help Treatment

- Rest to allow the injury to heal;

- Apply ice or cold therapy in the early stages, particularly when it is very painful. Cold therapy reduces pain and inflammation;

- Over-the-counter painkillers, such as ibuprofen or paracetamol, may also help by reducing the pain and inflammation. Follow the instructions in the patient information leaflet that comes with the medicine and if you have any questions, ask your pharmacist or medical professional for advice.

- Shin splint stretches should be done to stretch the muscles of the lower leg. In particular the tibialis posterior which is associated with shin splints;

- Wear shock absorbing insoles in shoes as this helps reduce the shock on the lower leg. Check your trainers or sports shoes to see whether they give enough support and cushioning. Specialist running shops can give you advice and information about your trainers. An experienced adviser can watch you run and recommend suitable shoes for you.

- Maintain fitness with other non-weight bearing exercises such as swimming, cycling or running in water;

- Apply heat and use a heat retainer or shin and calf support after the initial acute stage and particularly before training. This can provide support and compression to the lower leg helping to reduce the strain on the muscles. It will also retain the natural heat which causes blood vessels to dilate and increases the flow of blood to the tissues to aid healing; and/or

- Shin splints strengthening exercises may help prevent the injury returning.

It is important that you think about how much exercise you are doing and if it is causing shin splints. You may need to reduce the amount of exercise you are doing or change your training routine.

Non-surgical Treatment

A physiotherapist can help devise a graduated training programme to promote recovery and help you return to your usual sports activities. A physiotherapist can:

- Help to restore any loss of range to your lower limb joints and muscles that may be contributing to shin splints;

- Advise on a strengthening programme, especially to the calf muscle; and/or

- Use acupuncture, tape or soft tissue techniques that may help reduce pain.

A podiatrist (a health professional who specialises in conditions that affect the feet) can provide advice about foot care. S/he can also supply shoe inserts (orthotics) to control the inward roll of your feet if necessary.

Surgery

If your shin splints are caused by compartment syndrome and the pain is severe, your medical professional may suggest an operation called a fasciotomy. This releases the pressure on the muscles in your lower leg. Talk to your medical professional or physiotherapist for more information.

Other Things Your Medical Professional, Physiotherapist or Podiatrist May Do

- Tape the shin for support: a taping worn all day will allow the shin to rest properly by taking the pressure off the muscle attachments;

- Perform gait analysis to determine if you overpronate or oversupinate; and/or

- Use sports massage techniques on the posterior deep muscle compartment but avoid the inflamed periostium close to the bone.

Getting Back To Your Usual Exercise Programme

You can return to your usual activity after at least two weeks of rest, and only when the pain has gone. Increase your activity level slowly by gradually building up the time you spend running or doing sports. It is also important that you warm up and stretch before you start exercising. If the pain returns, stop immediately.

A sports physiotherapist will be able to advise you on a suitable graded running programme. You can ask your medical professional for a referral on the NHS or arrange an appointment yourself privately with a physiotherapist or medical professional specialising in sport and exercise medicine.

Prevention

The following steps can help reduce your risk of developing shin splints:

- Get fitted for supportive running shoes or wear supportive footwear that is appropriate for your sport or activity;

- Using shock-absorbing insoles or (if you have flat feet) insoles to support the foot better (your medical professional, podiatrist or physiotherapist can provide specialist advice on this);

- Avoid training on hard surfaces and exercise on a grass surface, if possible; and/or

- Build up your activity level gradually.

When to See Your Medical Professional

See your medical professional if the pain does not improve. They will investigate other possible causes, such as:

- Reduced blood supply to the lower leg;

- Tiny cracks in the shin bone (a stress fracture);

- A leg muscle bulging out of place (muscle hernia);

- Swelling of the leg muscle that compresses nearby nerves and blood vessels, known as compartment syndrome; and/or

- A nerve problem in your lower back, known as radiculopathy.

Further, see your medical professional immediately if the:

- Pain is severe and follows a fall or accident;

- Shin is hot and inflamed;

- Swelling getting worse; and/or

- Pain persists during rest.

Definitions

[1] Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs.

[2] The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

References

Bouchard, C., Blair, S.N. & Haskell, W.L. (2012) Physical Activity and Health. 2nd ed. London: Human Kinetics.

Knapick, J.J., Bullock, S.H., Canada, S. Toney, E., Wells, J.D., Hoedebecke, E. & Jones, B.H. (2004) Influence of an Injury Reduction Program on Injury and Fitness Outcomes among Soldiers. Injury Prevention. 10, pp.37-42.

Adult Learning Inspectorate (2005) Safer Training: Managing Risks to the Welfare of Recruits in the British Armed Services. Available from World Wide Web: <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/21_03_05_ali.pdf> [Accessed: 13 November, 2012].

Elliot, B. & Ackland, T. (1981) Biomechanical Effects of Fatigue on 10,000 Meter Racing Technique. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 52(2), pp.160-166.

Nyland, J.A., Shapiro, R., Stine, R.L., Horn, T.S. & Ireland, M.L. (1994) Relationship of Fatigued Run and Rapid Stop to Ground Reaction Forces, Lower Extremity Kinematics, and Muscle Activation. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 20(3), pp.132-137.

Mair, S.D., Seaber, A.V., Glisson, R.R. & Garrett, W.E. (1996) The Role of Fatigue in Susceptibility to Acute Muscle Strain Injury. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 24(2), pp.137-143.

Candau, R., Belli, A., Millet, G.Y., Georges, D., Barbier, B. & Rouillon, J.D. (1998) Energy Cost and Running Mechanics During a Treadmill Run to Voluntary Exhaustion in Humans. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 77(6), pp.479-485.

Stamford, B. (1996) Cross-training: Giving Yourself A Whole-body Workout. Physician and Sports Medicine. 24(9), pp.15–16.

Wilkinson, D.M., Blacker, S.D., Richmond, V.L., Horner, F.E., Rayson, M.P., Spiess, A. & Knapick, J.J. (2011) Injuries and Injury Risk Factors among British Army Infantry Soldiers during Predeployment Training. Injury Prevention. 17, pp.381-387.

Rolfe, A. & Boyce, S.H. (2011) Exercise Promotion in Primary Care. InnovAiT. 4(10), pp.569.

Albert, C.M., Mittleman, M.A., Chae, C.U., Lee, I.M., Hennekens, C.H. & Manson, J.E. (2000) Triggering of Sudden Death from Cardiac Disease Causes by Vigorous Exertion. New England Journal of Medicine. 343, pp.1355-1361.

Bookman, A.A., Williams, K.S. & Shainhouse, J.Z. (2004) Effect of a Topical Diclofenac Solution for Relieving Symptoms of Primary Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Randomized Control Trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 171(4), pp.333-338.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) (2008) The Care and Management of Osteoarthritis in Adults. London: NICE.

Bruckner, P. & Khan, K. (2006) Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd ed. Australia: McGraw.

Carr, K. & Sevetson, E. & Aukerman, D. (2008) How Can You Help Athletes Prevent and Treat Shin Splints? Journal of Family Practice. 57(6), pp.406-408.

MacAuley, D. (2007) Oxford Handbook of Sport and Exercise Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp.270-271.

Thacker, S., Gilchrist, J. & Stroup, D. (2002) The Prevention of Shin Splints in Sports: A Systematic Review of Literature. Medicine Science Sport Exercise. 34(1), pp.32-40.