Associated Pages

- Prevention & Rehabilitation: Military Perspective.

- DOMS: Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness.

- Elbow Tendonitis: Tennis & Golfer’s Elbow.

- Shin Splints.

- Achilles Tendon Disorders.

- Foot Care: Overview.

- Pushing and Pulling Overview.

- Lifting and Carrying Overview.

- CECS: Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome.

- Lisfranc Injuries: An Overview.

- Diastasis Recti: An Overview.

- Plantar Fasciitis: An Overview.

- An Overview of Piriformis Syndrome.

- Exercise & Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes (EDS).

Introduction

Apparently, the human body is designed for activity (Bouchard et al., 2012). Although with an increase in physical inactivity and increasingly sedentary lifestyles you would be forgiven for forgetting this.

For most of our history physical activity was required for survival but technological advances have eliminated much of the need for hard physical labour, and as our activity levels have dropped, it has become clear that a physically inactive lifestyle can lead to a host of health problems.

It is this reduced initial level of fitness of recruits that appears to cause many problems when it comes to injuries during initial military physical training. However, utilising interventions such as graduated training programmes and placing recruits into ability groups can ameliorate the effects of these reduced initial fitness levels, thereby reducing the likelihood of injury.

From injury prevention we will move onto injury symptoms, causes and potential treatments based on the more prevalent injuries I have witnessed over the last two decades whilst instructing both military and civilian fitness sessions, backed up by research literature.

Injury Prevention and Military Physical Training

The information provided within this section is not intended to act as a replacement to professional advice but merely to provide the reader with an overview of common issues associated with physical activity and exercise.

Numerous studies have been conducted on the issue of injury causes, prevention and treatment within the sphere of military training. Although the research will have methodological differences they generally reach broadly similar conclusions.

In a study based on US soldiers, Knapick et al. (2004) looked at physical fitness and injuries in two groups. After correcting for the lower initial fitness of the multiple intervention group, there were no significant differences between the multiple intervention and historical (traditional physical training) control groups in terms of improvements in push-ups, sit-ups, or two mile run performance. However, while improvements in physical fitness were similar, in their conclusions they argue that the multiple intervention programme contributed to a reduction in injuries (Knapick et al., 2004). The three interventions utilised for the study were the physical readiness training (PRT) programme (a graduated training programme), injury control education course and unit based injury survelliance system.

Knapick et al. (2004) also suggest another factor possibly associated with lower, multiple intervention group, injury rates may have been the ability group runs. It was observed that during historical control runs, the entire training group would run together but some individuals, presumed to have lower fitness, would drop out of the run. Ability group runs performed by the multiple intervention group permitted less fit soldiers to run at speeds more appropriate to their lower aerobic capacities and may have avoided excessive fatigue during the run that can be associated with gait changes (Elliot & Ackland, 1981; Nyland et al., 1994; Mair et al., 1996; Candau et al., 1998) and may be associated with injuries.

Another training related factor that may partially account for lower injury rates is the variety of exercises in the PRT programme (Knapick et al., 2004). Although there are no studies indicating that a greater variety of exercise will reduce injuries, sports medicine professionals often recommend cross training (different exercises on different days) for this purpose (Stamford, 1996). The Adult Learning Inspectorate in their 2005 report argue that these types of interventions would also be required for the UK military training system.

Knapick et al. (2004) illustrate how previous studies have shown that combining aspects of educational efforts with community leadership participation, modification of attitudes, behaviours and norms, and alterations in the physical environment can be effective in reducing injuries. The injury control education course covered physiological principles, physical training concepts, injury prevention research and techniques, application of risk management techniques, and practical exercises (Knapick et al., 2004).

Knapick et al. (2004) illustrate how previous studies have shown that combining aspects of educational efforts with community leadership participation, modification of attitudes, behaviours and norms, and alterations in the physical environment can be effective in reducing injuries. The injury control education course covered physiological principles, physical training concepts, injury prevention research and techniques, application of risk management techniques, and practical exercises (Knapick et al., 2004).

In another study based on 660 UK soldiers (Wilkinson et al., 2011) one or more injuries were experienced by 58.5% of soldiers with most injuries involving the lower body (71%), especially the lower back (14%), knee (19%) and ankle (15%). Activities associated with injury included physical training (30%), military training/work (26%) and sports (22%).

Traumatic injuries accounted for 83% of all injury diagnoses and independent risk factors for any injury were younger age and previous lower back injury. In their conclusions Wilkinson et al. (2011) suggested that future efforts should target reducing the incidence of traumatic injuries, especially those related to physical training and/or sports.

Injury Prevention and Boot Camps

The results from such research can also be used in the context of the ‘civilian’ boot camp market, where a combination of graduated training, variety of exercises, injury control education and injury surveillance can be applied. Knapick et al. (2004) suggest that these interventions are unlikely to make an individual physically fitter, however, they are likely to reduce the risk of injury for that individual; which is one of the major critiscisms by some sports scientists and fitness professionals regarding boot camp physical training programmes.

Graduated training can be applied by fitness professionals and training providers through:

- Fitness ability groups levels: most training providers divide their clients into three, sometimes more, fitness ability group levels.

- Progression and adaptation techniques: for example making an exercise easier or more difficult, or providing an alternative exercise for those building strength in specific areas or recovering from injury.

Although there is no direct evidence that a variety of exercises will reduce the likelihood of injury, boot camps are predicated on offering a variety of exercises, training techniques and training concepts through the ‘no typical session’ mantle. However, the degree of variety provided is dependent upon the specific instructor taking the session and their attitude, skills and knowledge.

Injury control education should cover physiological principles, physical training concepts, injury prevention research and techniques, application of risk management techniques, and practical exercises.

A ‘good’ or competent instructor should understand the above and pass this knowledge on to members as teaching points during the session, i.e. through demonstration of correct techniques and correctional development with individuals.

Within the boot camp sector injury data is not routinely collected, although some training providers do collect data within their accident and emergency procedures but this is filed for insurance purposes rather than for proactive survelliance.

Data likely to be collected includes date of birth, gender, race, venue, type of injury or illness, date of injury or illness and date of injury resolution or return to training. A simple spreadsheet can be used for data input and realtime graphs and charts can subsequently be generated.

Before starting an exercise programme, younger age has been identified as a risk factor for the increased likelihood of injury in thos with physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyles. The medical screening process should provide a more individual assessment of prior physical activity and identify those individuals at risk.

Previous lower back injuries or any other injuries should, theoretically, also be identified during the medical screening process but this relies on individual self-declaration, which causes problems even for medical professionals (see Induction & Medical Screening section). Individuals attending trial sessions, and subsequently, who self-declare or are identified with injuries of this nature should be referred to a medical professional for advice before continuing with an exercise programme.

Returning to Training from Inactivity

Injuries often recur because the return to normal training from a period of inactivity following an injury is too quick. An individual who has been injured and has therefore not attended physical training for several weeks could be at an increased risk of recurring injury for the following reasons:

- Loss of strength, flexibility or another fitness component;

- The training group has progressed to a more demanding physical training stage;

- Loss of the skill element needed for specific training;

- Confidence may have diminished; and/or

- Reduced group integration when performing group tasks.

The decision to return to training will primarily be an individual one. However, the decision may involve the indiviudal’s medical professional, physiotherapist and/or fitness professional. Regardless, prior to a return to training, an assessment should be conducted to identify the individual’s physical state. Assessments may incorporate supervised and recognised fitness testing relative to the physical training requirement, or the use of non-standard physical training tests, e.g. balancing or throwing tests. The use of such non-standard testing must be appropriate and, where appropriate, guidance sought from either a medical professional or physiotherapist.

If an individual is not able to return to normal physical training, provision should be made in the form of progressive fitness training starting at an appropriate level. This may entail remedial training and/or carrying out other specific training.

Risks of Exercise

Although for most people the benefits of exercise greatly outweigh the risks, there are some groups who need to be more careful. Those at greatest risk are those who undertake significant vigorous execise, change intensity of exercise suddenly, do excessive amounts of exercise or have existing musculoskeletal disease or other illness. It is therefore advisable that exercisers seek professional advice, increase exercise gradually, use common sense and allow the body time to recover and adapt.

Sporting injuries do occur and are often determined by the sport itself. Risks that can be minimised are training too hard, poor technique, change in training, poor condition, exercising on hard surfaces, poor footwear or poor equipment (Rolfe & Boyce, 2011).

A concern for medical and fitness professionals who encourage physical activity and exercise is the risk of sudden death. The risk of sudden death is 1 death per 1.5 million exercise hours in middle-aged men (Albert et al., 2000). Thus, althoug hthe risk of sudden deat his increased, this increase is exetremely small. The risk is lower in younger exercisers and women. Although in many cases no cause is found for sudden death, it is likely that underlying congential cardiac problems are responsible (Rolfe & Boyce, 2011).

Environmental factors can increase the risks of injury and exercisers should be advised about wearing high-visibility/reflective clothing, making sure the waether is suitable and an awareness of traffic and other hazards.

For small groups of the population there are psychological risks assocaited with exercise (Rolfe & Boyce, 2011). Exercisers who suffer severe injury can be absent from work for long periods and their mental state can suffer as a result. Some exercisers can develop an addiction to exercise which can interfere with their everyday functioning as they put their exercise before relationships, exercise excessively and suffer withdrawal if they are unable to complete their planned activity. It is thought that this is most likely due to an underlying psychological disorder rather than a physiological phenomenon (Rolfe & Boyce, 2011).

Other, more general, risks of increasing exercise include sunburn, dehydration, hyperthermia, hypothermia or heat stroke. Some activities such as swimming can increase the risk of bacterial infections. At high levels of exercise, there can be a degree of immunosuppression leading to recurrent viral infections. Some sports can cuase haematological disturbance, such as haematuria, and intestinal disturbances have been reported in long-distance endurance athletes (Rolfe & Boyce, 2011).

Injury Symptoms

There are many injuries related to physcial activity and these all come with their own symptoms, causes and potential treatments. However, this section is based on the more prevalent injuries I have witnessed over the last two decades, whilst instructing both military and civilian fitness sessions, and includes:

- DOMS (delayed onset of muscle soreness);

- Elbow tendonitis; and

- Shin splints.

Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS)

Delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS) describes a phenomenon of muscle pain, muscle soreness or muscle stiffness that is felt 12-48 hours after exercise, particularly at the beginning of a new exercise programme, after a change in sports activities, or after a dramatic increase in the duration or intensity of exercise.

This muscle pain is a normal response to unusual exertion and is part of an adaptation process that leads to greater stamina and strength as the muscles recover and hypertrophy.

This sort of muscle pain is not quite the same as the muscle pain experienced during exercise as a result of fatigue and is very different than the acute, sharp pain of a muscle injury, which is marked by sharp, specific and sudden pain that occurs during activity and often causes associated swelling or bruising.

The delayed soreness of DOMS is generally at its worst within the first two days following the activity and subsides over the next few days.

DOMS is common and quite annoying, particularly for those beginning an exercise programme or adding new activities. A person who is new to exercise who bikes 10 miles, followed by push-ups and sit-ups is likely to experience muscle pain and soreness in the next day or two.

DOMS: Causes

DOMS is thought to be a result of microscopic tearing of the muscle fibres. The amount of tearing (and soreness) depends on how hard (exercise intensity) and how long (exercise duration) you exercise and what type of exercise you do. Any movement that your muscle is unaccustomed to can lead to DOMS, but movements that cause muscle to forcefully contract while it lengthens (eccentric contractions) seem to cause the greatest pain.

Examples of eccentric muscle contractions include going down stairs, running downhill, lowering weights and the downward motion of squats and push-ups. In addition to small muscle tears there can be associated swelling in a muscle which may contribute to soreness.

DOMS: Treatment and Tips for Dealing with Muscle Soreness after Exercise

There is no one simple way to treat DOMS. In fact, there has been an ongoing debate about both the cause and treatment of DOMS. In the past, gentle stretching was one of the recommended ways to reduce exercise related muscle soreness, but a study by Australian researchers published in 2007 found that stretching is not effective in avoiding muscle soreness (WHO, WHEN).

So does anything work to reduce DOMS? Nothing has been proven to be 100% effective, but some people have found the following advice helpful, but it is best for an individual to try a few things to see what works for them. Ultimately, the best advice for treating DOMS is to prevent it in the first place.

If you do find yourself sore after a tough workout or competition, try these methods to deal with your discomfort. Although not all are backed up with research, many athletes report success with some of the following methods:

-

- Use Active Recovery: this strategy does have support in the research. Performing easy low-impact aerobic exercise increasing blood flow and is linked with diminished muscle soreness. After an intense workout or competition, use this technique as a part of your cool-down.

- Rest and Recover: if you simply wait it out, soreness will go away in 3 to 7 days with no special treatment.

- Try a Sports Massage: some research has found that sports massage may help reduce reported muscle soreness and reduce swelling, although it had no effects on muscle function.

- Try an Ice Bath or Contrast Water Bath: although no clear evidence proves they are effective, many professional athletes use them and claim they work to reduce soreness.

- Use the RICE method (Rest, Ice, Compression, & Elevation): the standard method of treating acute injuries, especially if your soreness is particularly severe.

- Perform Gentle Stretching: although research does not find stretching alone reduces muscle pain of soreness, many people find it simply feels good (i.e. it could be the placebo effect).

- Try a Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory: aspirin, ibuprofen or naproxen sodium may help to temporarily reduce the muscle soreness, although they will not actually speed healing. Be careful, however, if you plan to take them before exercise. Studies reported that taking ibuprofen before endurance exercise is not recommended.

- Try Yoga: there is growing support that performing Yoga may reduce DOMS.

- Listen to Your Body: avoid any vigorous activity or exercise that increases pain. Allow the soreness to subside thoroughly before performing any vigorous exercise.

- Warm-ups: warm-up completely before your next exercise session. There is some research that supports that a warm-up performed immediately prior to unaccustomed eccentric exercise produces small reductions in DOMS (but cool-down performed after exercise does not).

- Morale of the Story: learn something from the experience! Remember prevention is better than cure.

Certain muscle pain or soreness can be a sign of serious injury. If your pain persists longer than about seven days or increases despite these measures, consult your medical professional.

DOMS: Prevention

While you may not be able to prevent muscle soreness entirely, you may reduce the intensity and duration of muscle soreness if you follow a few exercise recommendations.

- Progress Slowly: The most important prevention method is to gradually increase your exercise time and intensity (see the 10% rule if you need some exercise progression guidelines).

- Warm-up thoroughly before activity and cool-down completely afterward.

- Cool-down with gentle stretching after exercise.

- Follow the 10% Rule: When beginning a new activity start gradually and build up your time and intensity no more than 10% per week.

- Speak to a fitness professional if you are not sure how to start a workout programme that is safe and effective.

- Avoid making sudden major changes in the type of exercise you do.

- Avoid making sudden major changes in the amount of time that you exercise.

Elbow Tendonitis: Tennis and Golfer’s Elbow

Background

Lateral epicondylitis or lateral epicondylalgia, better known as tennis elbow, is a condition where the outer part of the elbow becomes sore and tender. It is also called shooter’s elbow, archer’s elbow or simply lateral elbow pain.

Since the pathogenesis of this condition is still unknown, there is no single agreed name. While the common name ‘tennis elbow’ suggests a strong link to racquet sports, this condition can also be caused by sports such as swimming and climbing, the work of manual workers and waiters, as well as activities of daily living (ADL).

Tennis elbow is an overuse injury occurring in the lateral side of the elbow region, but more specifically it occurs at the common extensor tendon that originates from the lateral epicondyle of the humerous. Acute pain is experienced as the arm is extended. Overuse injury can also affect the back (posterior) part of the elbow as well.

Tennis elbow is an overuse injury occurring in the lateral side of the elbow region, but more specifically it occurs at the common extensor tendon that originates from the lateral epicondyle of the humerous. Acute pain is experienced as the arm is extended. Overuse injury can also affect the back (posterior) part of the elbow as well.

- Tennis elbow: pain in the outer (lateral) part of the elbow; and

- Golfer’s elbow: pain in the inner (medial) part of the elbow.

In one study, data was collected from 113 patients who had tennis elbow and the main factor common to them all was overexertion. Sportspersons as well as those who used the same repetitive motion for many years, especially in their profession, suffered from tennis elbow. It was also common in individuals who performed motions they were unaccustomed to. The data also mentioned that the majority of patients suffered tennis elbow in their right arms.

The Elbow Joint

The elbow joint is surrounded by muscles that move the elbow, wrist and fingers. The tendons at your elbow join the muscles of the forearm to the bones and along with the muscles, control movement of the wrist and hand.

The elbow joint is surrounded by muscles that move the elbow, wrist and fingers. The tendons at your elbow join the muscles of the forearm to the bones and along with the muscles, control movement of the wrist and hand.

When a person gets tennis elbow, one or more of the tendons on the lateral aspect of the elbow becomes painful. The pain occurs at the point where the tendons attach to the bone. Twisting movements, such as turning a door handle or opening the lid of a jar, are particularly painful.

In around three quarters of cases of tennis elbow, the dominant hand (the one that is used the most) is affected.

How Common is Tennis Elbow

Tennis elbow is fairly uncommon. Approximately 5 in every 1,000 adults in the UK are affected by the condition each year. Tennis elbow usually occurs in adults and men and woman are affected equally. The condition tends to affect people who are around 40 years old.

Symptoms: Tennis Elbow

The main symptom of tennis elbow is pain and tenderness on the outside of your elbow. You may also feel pain travelling down your forearm. It can vary in severity, but you will usually have the symptoms listed below:

- Recurring pain on the outside of your upper forearm, just below the bend of your elbow. Sometimes, you may also feel pain down your forearm towards your wrist;

- Pain caused by lifting or bending your arm;

- Pain when writing or when gripping small objects. This can make it difficult to hold small items, such as a pen;

- Pain when twisting your forearm. For example, when turning a door handle or opening a jar; and/or

- Difficulty fully extending your forearm.

The pain of tennis elbow can range from mild discomfort when using your elbow to severe pain that can be felt even when your elbow is still or when you are asleep. You may have stiffness in your arm that gets progressively worse as the damage to your tendon increases.

As you and your body try to compensate for the weakness in your elbow, you may also have pain or stiffness in other parts of the affected arm or in your shoulder and neck.

On average, a typical episode of tennis elbow lasts between six months and two years. Most people (90%) make a full recovery within a year.

How is Golfer’s Elbow Different

Golfer’s elbow (medial epicondylitis) causes pain and inflammation at the point where the flexor tendons of the forearm are attached to the upper arm. The pain centres on the bony bump on the inside of your elbow and may radiate into the forearm. It can usually be treated effectively with rest.

Golfer’s elbow is usually caused by overuse of the muscles in the forearm that allow you to rotate your arm and flex your wrist. Repetitive flexing, gripping or swinging can cause pulls or tiny tears in the tendons close to where they are attached to the bone.

Both tennis elbow and golfer’s elbow are forms of elbow tendinitis. The difference is that tennis elbow stems from damage to the extensor tendons on the outside of the elbow, while golfer’s elbow is caused by flexor tendons on the inside.

Symptoms: Golfer’s Elbow

The primary symptom of golfer’s elbow is pain that is centred near the bony knob on the inside of the elbow. Sometimes it extends all along the inner forearm. You are most likely to feel it when you bend your arm inwards or flex your wrist towards the body. In most cases, the pain becomes gradually worse.

Causes & Risk Factors of Elbow Tendonitis

Elbow tendonitis is caused by small tears in the muscles of the forearm due to overuse of the muscles or minor injury. It can also occur as the result of a single, forceful injury.

Excessive or repeated use of the muscles that straighten your wrist can injure the tendons in your arm and elbow and lead to tiny tears, which cause rough tissue to form near the bony lump on the outside of your elbow.

Elbow tendonitis often occurs after you do an activity that uses your forearm muscles when you have not used them much in the past. However, even if you use your forearm muscles frequently, it is still possible to injure them and develop elbow tendonitis. You are more at risk of developing elbow tendonitis if the tendons in your elbow can be injured by overusing your forearm muscles in repeated actions, such as:

- Gardening, e.g. using shears;

- Playing racquet sports, such as tennis or squash;

- Sports that involve throwing, such as the javelin or discus; and/or

- Swimming.

Elbow tendonitis can also develop in the workplace through carrying out repetitive tasks and actions, such as:

- Manual work that involves repetitive turning or lifting of the wrist, such as plumbing or bricklaying; and/or

- Repetitive, fine movements of the hand and wrist, such as typing or using scissors.

Your risk of developing tennis elbow increases if you regularly play racquet sports, such as tennis or squash, or if you play a racquet sport for the first time in a long time. However, despite its name, only 5 out of 100 people develop tennis elbow through playing racquet sports such as tennis.

Diagnosis

You should visit your medical professional if the symptoms do not improve after you have avoided or modified the activity that is causing the problem, or if ordinary painkillers such as paracetamol are not effective.

Your medical professional can make a diagnosis based on your symptoms and by examining your arm; checking for pain in the area around your elbow. Your medical professional may also ask you several questions to help confirm a diagnosis. For example, they may ask you about your job and any leisure or sports activities that you do. Remember, your work and sport activities are not mutually exclusive when it comes to placing stress on your muscles and joints. For example, it could be:

- Your sport activity led to the injury and your work activity exacerbates it; or

- Your work activity led to the injury and your sport activity exacerbates it;

Further Investigations

Further investigations are not usually needed to diagnose either tennis elbow or golfer’s elbow. This is because these conditions can usually be confirmed after your medical professional examines your arm (i.e. a clinical diagnosis). However, if your medical professional suspects that your pain is caused by nerve damage in your arm, they may want to refer you for a more detailed examination. The two types of investigations that may be used are:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan: A MRI scan uses a strong magnetic field and radio waves to produce a detailed image of the inside of your body. The scan will also show if any pressure is being placed on your nerve and is causing your pain; or

- Ultrasound scan: An ultrasound scan uses high-frequency sound waves to create an image of part of the inside of your body.

However, since there are many other conditions that can cause pain around the elbow, it is important that you seek medical advice so the correct diagnosis can be made. Then your medical professional can prescribe the appropriate treatment.

Treatment Options and Outlook

Both conditions are self-limiting and this means that in the majority of cases the symptoms eventually improve and clear up without treatment. Most cases last between six months and two years, this is because tendons are slow to heal. However, in around 9 out of 10 cases, a full recovery is made within one year.

There are medical (non-surgical) and surgical treatment options for tennis and golfer’s elbow. Medical treatments are tried first and in general surgery will only be recommended as a treatment of last resort, after failure to improve with medical treatments.

The type of treatment recommended will depend on several factors including age, type of other medications being taken, overall health, medical history and severity of pain. The goals of treatment are to reduce pain or inflammation, promote healing and to decrease stress and abuse of the injured elbow, in order to return to normal elbow function.

Medical (Non-surgical) Treatments

If you have elbow tendonitis, the most important method of management is rest. You should rest the affected arm as much as possible and avoid doing any activities that put more stress on the tendons.

Taking painkillers, such as paracetamol and ibuprofen (NSAIDs[1]), may help to reduce mild pain that is caused by elbow tendonitis. Children under 16 years old should not take aspirin. Ibuprofen also has anti-inflammatory properties, so helps reduce associated inflammation and swelling.

NSAIDs are also available as creams and gels, known as topical NSAIDs. These are applied directly to a specific area of your body, such as your forearm or elbow. Some NSAIDs are available over the counter at a pharmacy while others are only available on prescription. Your pharmacist or medical professional can advise you about which NSAID is most suitable for you. Examples of topical NSAIDs include:

- Ibuprofen;

- Diclofenac;

- Ketoprofen; and

- Piroxicam.

These have been proven to provide some pain relief and reduce inflammation for musculoskeletal conditions (those that affect the muscles or bones). There is strong evidence from research that topical NSAIDs are effective in improving pain, stiffness and function, in particular, in osteoarthritis of the knee (Bookman et al., 2004; NICE, 2008).

Anti-inflammatory creams and gels are often recommended for tennis elbow rather than anti-inflammatory tablets. This is because gels and creams provide effective pain relief and reduce inflammation without causing side effects, such as nausea, irritation of the stomach lining and diarrhoea.

NSAID creams or gels should be gently rubbed into the area that is causing pain and discomfort. Make sure that you read the patient information leaflet that comes with your cream or gel to check how often the treatment should be applied.

Avoid using topical NSAIDs during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Many topical NSAIDs are also unsuitable for children. Ask your pharmacist or medical professional for advice if you are not sure about whether a topical NSAID is suitable for you or your child.

Corticosteroid Injections

A corticosteroid injection may be recommended if: your symptoms are prolonged; your pain is severe; your elbow function is grossly limited; or NSAIDs have been ineffective. Corticosteroids are a medication that contains steroids (a type of hormone) that helps to reduce inflammation.

The injection will be made directly into the painful area around your elbow. You may be given a local anaesthetic to numb the area to reduce pain while the injection is being given. But steroids are often injected along with a local anaesthetic to provide immediate pain relief while the steroids takes time to work.

Most people who have a corticosteroid injection find that their pain initially improves significantly. However, a study of 198 people has shown that corticosteroid injection treatment is only effective in the short-term (around six weeks), and its long-term effectiveness is poor.

Research has shown that when compared to physiotherapy and a ‘wait and see’ approach to see if symptoms disappear naturally, corticosteroid injections were not as effective at 52 weeks. However, they were effective in the short term, at six weeks after the treatment. High recurrence rates have also been reported in people who have corticosteroid injections.

The recommended time in between corticosteroid injections is six weeks and the potential side effects of corticosteroid injections include:

- Pain in the affected area after having the injection;

- Skin de-pigmentation – the loss of colour (pigment) around the injection site; and

- Wasting away of the surrounding subcutaneous tissue (the layer of tissue beneath the surface of the skin).

Before you decide to have corticosteroid injections to treat elbow tendonitis, discuss the effectiveness and potential side effects with your medical professional. This will enable you to make a well-informed decision about this type of treatment.

After having a steroid injection (or injections), take care to rest your arm. Avoid putting too much strain on it too quickly. As with any injury, you should gradually build up to your normal activity levels to help prevent the problem reoccurring.

Physiotherapy

If your elbow tendonitis symptoms are particularly severe or persistent despite rest and use of NSAIDs, your medical professional may refer you to a physiotherapist. A physiotherapost is a healthcare professional who is trained to use physical methods, such as massage and manipulation, to promote healing.

A physiotherapist will be able to show you exercises to help stretch and strengthen your forearm muscles. They may also recommend that you wear a splint (an elasticated band that is positioned just below the elbow joint) to help support your elbow and encourage the tendons to heal.

Shock Wave Therapy

Shock wave therapy is where high-energy sound waves, like ultrasound, are passed through the skin of the affected area to help relieve the pain of elbow tendonitis and improve mobility (movement), this is normally performed by physiotherapists. The theory is that the shock waves stimulate blood flow to the tendons thus aiding healing.

Depending on the severity of your pain, shock wave therapy may be given once or it may be repeated. You may have a local anaesthetic during the procedure to prevent you feeling any pain while the shock waves are being passed through your skin. Following shock wave therapy, potential side effects include:

- Bruising;

- Red skin;

- Inflammation (swelling) of the skin; and/or

- Skin damage around the area being treated.

Research has shown that shock wave therapy is safe. However, NICE[2] (2009) states that there is a lack of evidence of its effectiveness in treating tennis elbow, and more research is required.

Your medical professional or physiotherapist may recommend shock wave therapy if other non-surgical treatments have proved to be ineffective in relieving your symptoms of tennis elbow. Discuss the potential risks, benefits and side effects with your medical professional or physiotherapist.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is a type of complementary treatment where fine needles are inserted into the skin around the affected area. In some cases, this may reduce pain and improve movement. However, there is a lack of evidence that it relieves the symptoms of tennis elbow.

Surgery

Surgery may be recommended as a last resort treatment option in rare cases of severe or persistent elbow tendonitis. Surgery aims to relieve the painful symptoms by removing the damaged part of the tendon.

Prevention

It is often difficult to prevent elbow tendonitis. However, avoiding putting too much stress on the tendons of your elbow will help you to avoid the condition or to prevent your symptoms from getting worse.

Self-care advice

There are a number of measures that you can take to help prevent elbow tendonitis developing or prevent it reoccurring:

- If you have elbow tendonitis, stop doing the activity that is causing pain, or find an alternative way of doing it that does not place stress on your tendons;

- Rather than using your wrist and elbow more than the rest of your arm, try spreading the load to the larger muscles of your shoulder and upper arm;

- If you play a sport that uses repetitive movements, such as tennis, you could get professional advice about your technique so that you do not strain your elbow;

- Before playing a sport that involves repetitive arm movements, such as tennis or squash, warm up beforehand and gently stretch your arm muscles to help you avoid injury;

- Use lightweight tools or racquets, and enlarge their grip size, to help you avoid putting excess strain on your tendons;

- Wear a tennis elbow splint when you are using your arm, and take it off while you are resting or sleeping to help prevent further damage to your tendons. Ask your medical professional or physiotherapist for advice about the best type of brace or splint for you to use; and/or

- Increasing the strength of your forearm muscles can help prevent tennis elbow. A physiotherapist can advise you about suitable exercises to build up the muscles of your forearm.

Shin Splints

Background

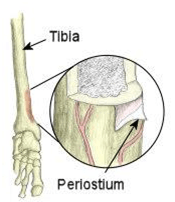

Your shin bone (tibia) is the bone at the front of your lower leg that runs from your knee to your ankle.

Shin splint’s is a general term used to describe any condition that causes pain down the middle, or on either side of your shin. Exercise-induced pain usually manifests itself in the front aspect of the lower legs. The medical name for this is medial tibial stress syndrome. The underlying problem is inflammation of the outer covering of the bone (periosteum).

Depending on the type of injury you have, the pain may come on gradually or you may have a sudden twinge of pain. Shin splints usually develop in people who do repetitive activities and sports – either during or after strenuous activity – that put a lot of stress on the lower legs, such as running, dancing, aerobics, gymnastics, football and hockey; i.e. sports with sudden stops and starts. Some soldiers also complain of shin splints during loaded marches.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of shin splints include:

- Tenderness along the front, or inside, of the lower leg;

- Aching or sharp pain along the front, or inside, of the lower leg;

- Pain at the start of exercise which often eases as the session continues;

- Pain often returns after activity and may be at its worse the next morning;

- Sometimes some swelling;

- Lumps and bumps may be felt when feeling the inside of the shin bone;

- Pain when the toes or foot are bent downwards; and/or

- Redness over the inside of the shin (not always present).

The pain is often worse when you do activities that involve supporting your body weight. You may feel pain along the whole length of your shin, or only along a small section.

The pain may build up during exercise and it will become more severe the longer you exercise, and if you ignore it and continue exercising it can become extremely painful and force you to stop sport altogether.

The pain may build up during exercise and it will become more severe the longer you exercise, and if you ignore it and continue exercising it can become extremely painful and force you to stop sport altogether.

It is really important not to ‘run through the pain’, as the shin pain is a sign of injury to the bone and surrounding tissues in your leg. Continued force on the legs will make the injury and your pain worse.

Instead, you should rest and take a break from the sport for at least two weeks. You can still exercise during this time off, but choose activities that will not put too much force on your shins, such as cycling or swimming.

Causes & Risk Factors

Shin splints can be caused by a number of factors which are mainly biomechanical (abnormal movement patterns) and errors in training. Here are the most common causes:

- Overpronation of the feet (rolling feet inwards);

- Oversupination of the feet (rolling feet outwards);

- Inadequate footwear;

- Increasing training too quickly;

- Running on hard surfaces;

- Decreased flexibility at the ankle joint;

- Stress fractures: these are an overuse injury. They develop after repeated periods of stress on your bones; for example, running or dancing over a long period of time; and

- Compartment syndrome: this happens when your muscle swells. Your muscle is within a close compartment and so does not have much room to expand. When the pressure in your muscle increases it causes the symptoms of compartment syndrome.

All of these conditions can develop when you put too much stress and strain on your shin bone. This happens when there is repetitive impact on your shin bone during weight-bearing sports or activities. You are more at risk of developing shin splints if:

- You increase your running distance;

- You are an inexperienced runner;

- Your sport or activity involves running or jumping on a hard surface;

- You do a lot of hill running;

- You increase your frequency of running and do not allow a rest day between runs;

- Your shoes do not fit well or do not have enough cushioning and support;

- You are overweight, as this places extra weight on your legs;

- You have weak ankles or a tight Achilles tendon (band of tissue connecting the heel bone to the calf muscle);

- You have flat feet or your feet roll inwards (pronate), as this places more pressure on the lower leg;

- You change your running pattern and the surface that you run on; for example, going from running on a treadmill to running on the road; and/or

- You participate in loaded marches, especially when unconditioned.

Rest and Recovery

You should rest your injury and think about what may have caused your shin splints.

You should be able to recover fully from shin splints if you rest for at least two weeks. This means you should not do any running or ‘stop and start’ sports during this time, although walking, swimming and cycling are OK.

Pain and any swelling can be relieved by raising your leg and holding an ice pack to your shin (try a bag of frozen peas wrapped in a tea towel). Do this for 10 minutes every few hours for the first two days. However, you should also consider the treatment options outlined below.

Treatment Options

Treatment for shin splints involves identifying training and biomechanical problems which may have caused the injury initially. Rest to allow muscles to return to their original condition and gradually return to training.

Self-help Treatment

- Rest to allow the injury to heal;

- Apply ice or cold therapy in the early stages, particularly when it is very painful. Cold therapy reduces pain and inflammation;

- Over-the-counter painkillers, such as ibuprofen or paracetamol, may also help by reducing the pain and inflammation. Follow the instructions in the patient information leaflet that comes with the medicine and if you have any questions, ask your pharmacist or medical professional for advice.

- Shin splint stretches should be done to stretch the muscles of the lower leg. In particular the tibialis posterior which is associated with shin splints;

- Wear shock absorbing insoles in shoes as this helps reduce the shock on the lower leg. Check your trainers or sports shoes to see whether they give enough support and cushioning. Specialist running shops can give you advice and information about your trainers. An experienced adviser can watch you run and recommend suitable shoes for you.

- Maintain fitness with other non-weight bearing exercises such as swimming, cycling or running in water;

- Apply heat and use a heat retainer or shin and calf support after the initial acute stage and particularly before training. This can provide support and compression to the lower leg helping to reduce the strain on the muscles. It will also retain the natural heat which causes blood vessels to dilate and increases the flow of blood to the tissues to aid healing; and/or

- Shin splints strengthening exercises may help prevent the injury returning.

It is important that you think about how much exercise you are doing and if it is causing shin splints. You may need to reduce the amount of exercise you are doing or change your training routine.

Non-surgical Treatment

A physiotherapist can help devise a graduated training programme to promote recovery and help you return to your usual sports activities. A physiotherapist can:

- Help to restore any loss of range to your lower limb joints and muscles that may be contributing to shin splints;

- Advise on a strengthening programme, especially to the calf muscle; and/or

- Use acupuncture, tape or soft tissue techniques that may help reduce pain.

A podiatrist (a health professional who specialises in conditions that affect the feet) can provide advice about foot care. S/he can also supply shoe inserts (orthotics) to control the inward roll of your feet if necessary.

Surgery

If your shin splints are caused by compartment syndrome and the pain is severe, your medical professional may suggest an operation called a fasciotomy. This releases the pressure on the muscles in your lower leg. Talk to your medical professional or physiotherapist for more information.

Other Things Your Medical Professional, Physiotherapist or Podiatrist May Do

- Tape the shin for support: a taping worn all day will allow the shin to rest properly by taking the pressure off the muscle attachments;

- Perform gait analysis to determine if you overpronate or oversupinate; and/or

- Use sports massage techniques on the posterior deep muscle compartment but avoid the inflamed periostium close to the bone.

Getting Back To Your Usual Exercise Programme

You can return to your usual activity after at least two weeks of rest, and only when the pain has gone. Increase your activity level slowly by gradually building up the time you spend running or doing sports. It is also important that you warm up and stretch before you start exercising. If the pain returns, stop immediately.

A sports physiotherapist will be able to advise you on a suitable graded running programme. You can ask your medical professional for a referral on the NHS or arrange an appointment yourself privately with a physiotherapist or medical professional specialising in sport and exercise medicine.

Prevention

The following steps can help reduce your risk of developing shin splints:

- Get fitted for supportive running shoes or wear supportive footwear that is appropriate for your sport or activity;

- Using shock-absorbing insoles or (if you have flat feet) insoles to support the foot better (your medical professional, podiatrist or physiotherapist can provide specialist advice on this);

- Avoid training on hard surfaces and exercise on a grass surface, if possible; and/or

- Build up your activity level gradually.

When to See Your Medical Professional

See your medical professional if the pain does not improve. They will investigate other possible causes, such as:

- Reduced blood supply to the lower leg;

- Tiny cracks in the shin bone (a stress fracture);

- A leg muscle bulging out of place (muscle hernia);

- Swelling of the leg muscle that compresses nearby nerves and blood vessels, known as compartment syndrome; and/or

- A nerve problem in your lower back, known as radiculopathy.

Further, see your medical professional immediately if the:

- Pain is severe and follows a fall or accident;

- Shin is hot and inflamed;

- Swelling getting worse; and/or

- Pain persists during rest.

Definitions

[1] Non-steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs.

[2] The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

References

Bouchard, C., Blair, S.N. & Haskell, W.L. (2012) Physical Activity and Health. 2nd ed. London: Human Kinetics.

Knapick, J.J., Bullock, S.H., Canada, S. Toney, E., Wells, J.D., Hoedebecke, E. & Jones, B.H. (2004) Influence of an Injury Reduction Program on Injury and Fitness Outcomes among Soldiers. Injury Prevention. 10, pp.37-42.

Adult Learning Inspectorate (2005) Safer Training: Managing Risks to the Welfare of Recruits in the British Armed Services. Available from World Wide Web: <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/21_03_05_ali.pdf> [Accessed: 13 November, 2012].

Elliot, B. & Ackland, T. (1981) Biomechanical Effects of Fatigue on 10,000 Meter Racing Technique. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 52(2), pp.160-166.

Nyland, J.A., Shapiro, R., Stine, R.L., Horn, T.S. & Ireland, M.L. (1994) Relationship of Fatigued Run and Rapid Stop to Ground Reaction Forces, Lower Extremity Kinematics, and Muscle Activation. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 20(3), pp.132-137.

Mair, S.D., Seaber, A.V., Glisson, R.R. & Garrett, W.E. (1996) The Role of Fatigue in Susceptibility to Acute Muscle Strain Injury. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 24(2), pp.137-143.

Candau, R., Belli, A., Millet, G.Y., Georges, D., Barbier, B. & Rouillon, J.D. (1998) Energy Cost and Running Mechanics During a Treadmill Run to Voluntary Exhaustion in Humans. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 77(6), pp.479-485.

Stamford, B. (1996) Cross-training: Giving Yourself A Whole-body Workout. Physician and Sports Medicine. 24(9), pp.15–16.

Wilkinson, D.M., Blacker, S.D., Richmond, V.L., Horner, F.E., Rayson, M.P., Spiess, A. & Knapick, J.J. (2011) Injuries and Injury Risk Factors among British Army Infantry Soldiers during Predeployment Training. Injury Prevention. 17, pp.381-387.

Rolfe, A. & Boyce, S.H. (2011) Exercise Promotion in Primary Care. InnovAiT. 4(10), pp.569.

Albert, C.M., Mittleman, M.A., Chae, C.U., Lee, I.M., Hennekens, C.H. & Manson, J.E. (2000) Triggering of Sudden Death from Cardiac Disease Causes by Vigorous Exertion. New England Journal of Medicine. 343, pp.1355-1361.

Bookman, A.A., Williams, K.S. & Shainhouse, J.Z. (2004) Effect of a Topical Diclofenac Solution for Relieving Symptoms of Primary Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Randomized Control Trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 171(4), pp.333-338.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) (2008) The Care and Management of Osteoarthritis in Adults. London: NICE.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence) (2009) Interventional Procedure Guidance 313: Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy for Refractory Tennis Elbow. London: NICE.

Arthritis Research UK (2011) Tennis Elbow. Available from World Wide Web: <www.arthritisresearchuk.org> [Accessed 16 May, 2011].

BMF (British Military Fitness) (2012a) How It Started. Available from World Wide Web: <http://www.britmilfit.com/about-bmf/how-it-started/> [Accessed: 08 November, 2012].

BMJ (British Medical Journal) Tennis Elbow. BMJ Best Practice. Available from World Wide Web: <www.bestpractice.bmj.com> [Accessed: 28 May, 2008].

Bruckner, P. & Khan, K. (2006) Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd ed. Australia: McGraw.

Carr, K. & Sevetson, E. & Aukerman, D. (2008) How Can You Help Athletes Prevent and Treat Shin Splints? Journal of Family Practice. 57(6), pp.406-408.

Cheung, K., Hume, P. & Maxwell, L. (2003) Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness: Treatment Strategies and Performance Factors. Sport Medicine. 33(2), pp.145-164.

eMedicine (2009) Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation for Lateral Epicondylitis. Available from World Wide Web: <http://www.emedicine.medscape.com> [Accessed: 24 July, 2009].

MacAuley, D. (2007) Oxford Handbook of Sport and Exercise Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp.270-271.

Orchard, J. & Kountouris, A. (2011) The Management of Tennis Elbow. British Medical Journal. 342, pp.26-87.

Thacker, S., Gilchrist, J. & Stroup, D. (2002) The Prevention of Shin Splints in Sports: A Systematic Review of Literature. Medicine Science Sport Exercise. 34(1), pp.32-40.