Part One: Background

Introduction

The classic press-up, or push-up in the US vernacular, has survived the test of time, and is the single most efficient exercise to simultaneously strengthen the chest, arms, deltoids, lower back, abs and the glutes. In simple terms, an equal effort is required to lower your body and raise it back up, and it is this controlled pace that works muscles as a team through three types of muscle-building resistance – concentric, eccentric and isometric.

The benefits of press-ups are plentiful. Press-ups will improve muscular endurance within the upper body, strengthen both muscles and bones, create lean muscle mass that raises your metabolism and, of course, help keep you fit and healthy.

If you are just looking to develop a great chest, arms and shoulders, you could do much worse than press-ups. You will also be surprised as your core strength increases too.

People lose up to 2% of muscle mass per year, eventually losing as much as 50% of muscle mass in the course of a lifetime. The effects of losing muscle mass include a decrease in strength, greater susceptibility to injury, and an increase in body fat.

The good news, however, is regular exercise enlarges muscle fibres and will stave off the decline by increasing the strength of muscle you have left. In fact, in many cases, strength training has been proven to reverse the loss of muscle mass and bone density due to aging.

The press-up is a core exercise in any fitness professional’s arsenal.

History of the Classic Press-up

The origins of the press-up are not totally clear, although several known variations have been in existence for centuries. One school of thought is that the press-up as we know it today is a joining together of two popular yoga poses; downward facing dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) and the upward facing dog (Urdhva Mukha Svanasana). The roots of yoga can be traced back over 3,000 years.

The origins of the press-up are not totally clear, although several known variations have been in existence for centuries. One school of thought is that the press-up as we know it today is a joining together of two popular yoga poses; downward facing dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) and the upward facing dog (Urdhva Mukha Svanasana). The roots of yoga can be traced back over 3,000 years.

Early examples of the exercise are also cited in Indian culture, where wrestlers would perform many hundreds of ‘Hindu push-up’ repetitions. Dands, as they are more commonly known, build massive upper body strength and endurance, and have been used by champion Indian wrestlers for years.

For the record, the phrase ‘push-up’ was first recorded in the United States during the period from 1905 to 1910. However, some forty years later, the (correct) phrase ‘press-up’ first appeared in the British lexicon.

Part Two: Defining the Press-up

What is a Press-up?

A press-up (a common calisthenics exercise) is a compound strength-training exercise that involves raising and lowering the body using the arms while facing down in a prone, horizontal position.

A compound exercise works several muscle groups at once, and includes movement around two or more joints. Most compound exercises build strength that is needed to perform everyday activities, and press-ups are no exception.

The Muscles behind the Movement

One of the greatest benefits of press-ups (and strength training in general) is that of injury prevention. Nothing aids the skeletal structure more than strengthening the muscles and connective tissue around a specific area.

One of the greatest benefits of press-ups (and strength training in general) is that of injury prevention. Nothing aids the skeletal structure more than strengthening the muscles and connective tissue around a specific area.

This strengthening naturally occurs through regular training and from an aerobic standpoint performing moderate to high sets of press-ups will provide an effective cardiovascular workout too. As an additional benefit, bone density is also improved, which vastly decreases the potential risk of injury in the specific body areas.

Press-ups are often considered difficult because the core stabiliser muscles of the hips and shoulders must be used to balance the body. Press-ups use all the muscles that make up the shoulder girdle and strengthen the smaller stabiliser muscles of the shoulder. The shoulder is responsible for daily actions such as lifting, pushing and pulling. Press-ups help to develop strength and flexibility for the wide range of motion required in the arms and hands. This strength and flexibility is especially important because the shoulder is extremely unstable and far more prone to dislocation and injury than other joints.

There are a number of other muscles involved in a press-up, as outlined in Table 1:

| Table 1: Muscles involved in a press-up | |

| Muscle | Description |

| Pectorals |

|

| Triceps |

|

| Deltoids |

|

| Serratus Anterior |

|

| Rectus Abdominis |

|

| Gluteas Maximus |

|

| Biceps Brachii |

|

The Role of the Various Muscles

- Target: pectoralis major (sterna)

- Synergists: pectoralis major (clavicular), deltoid (anterior) and triceps brachii

- Dynamic Stabilisers: biceps brachii, short head

- Stabilisers: rectus abdominis, obliques and quadriceps

- Antagonist Stabilisers: erector spinae

Why Press-ups?

Press-ups are functional, multi-joint, multi-muscle movements that mimic the actions and movements we perform on an everyday basis.

In a nutshell, press-ups give you more strength to carry out the activities you do every day: lifting, carrying, moving, cleaning and gardening.

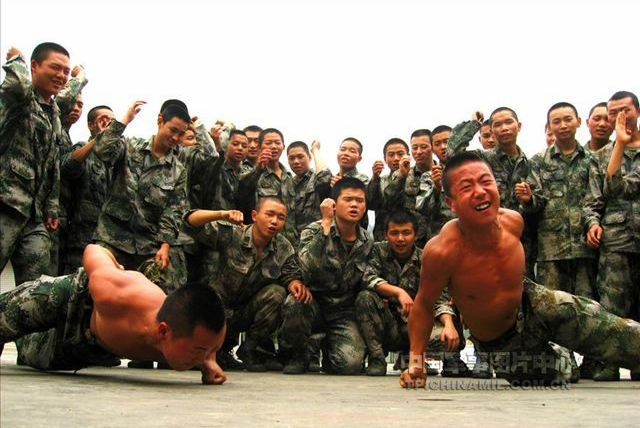

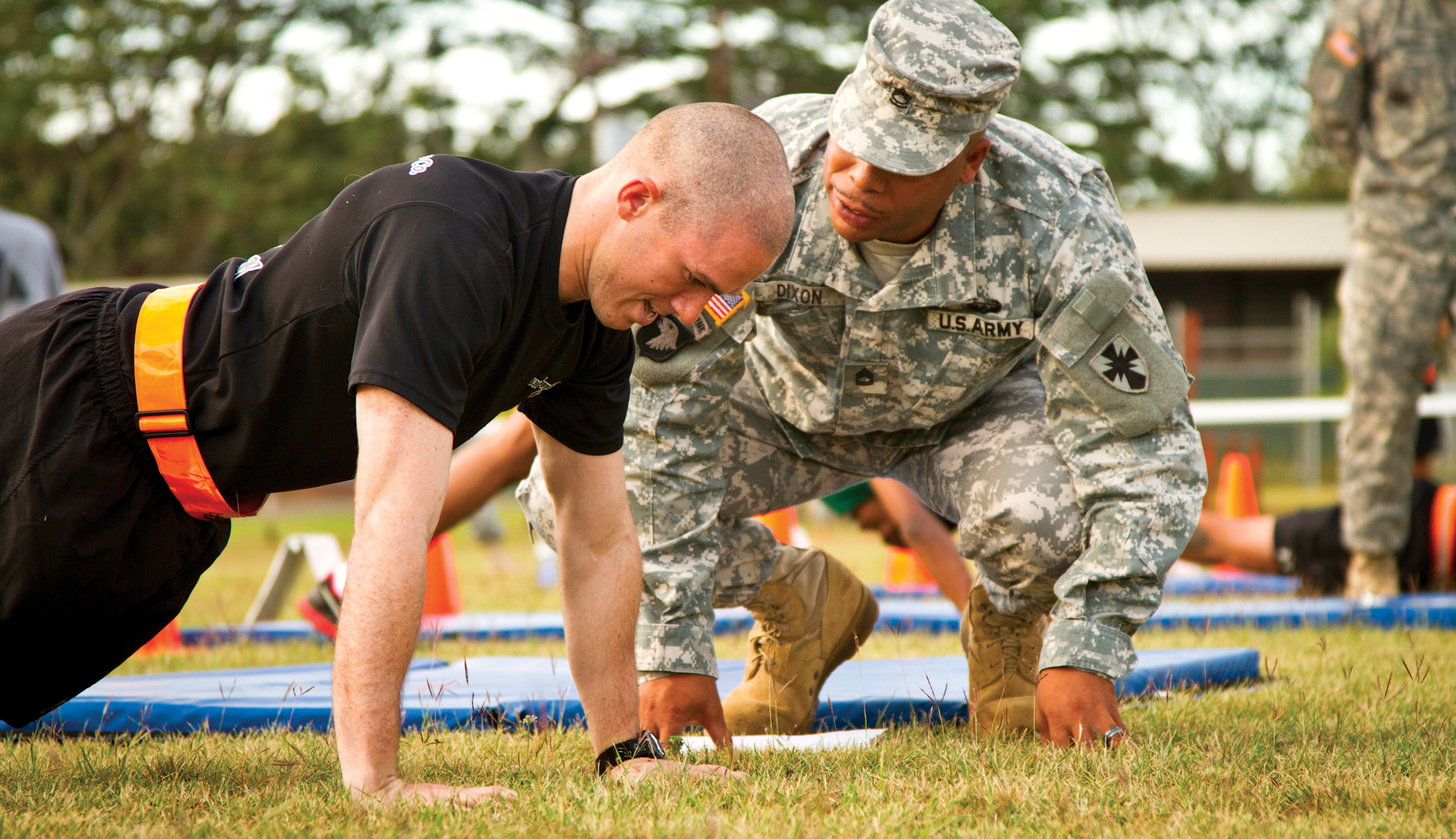

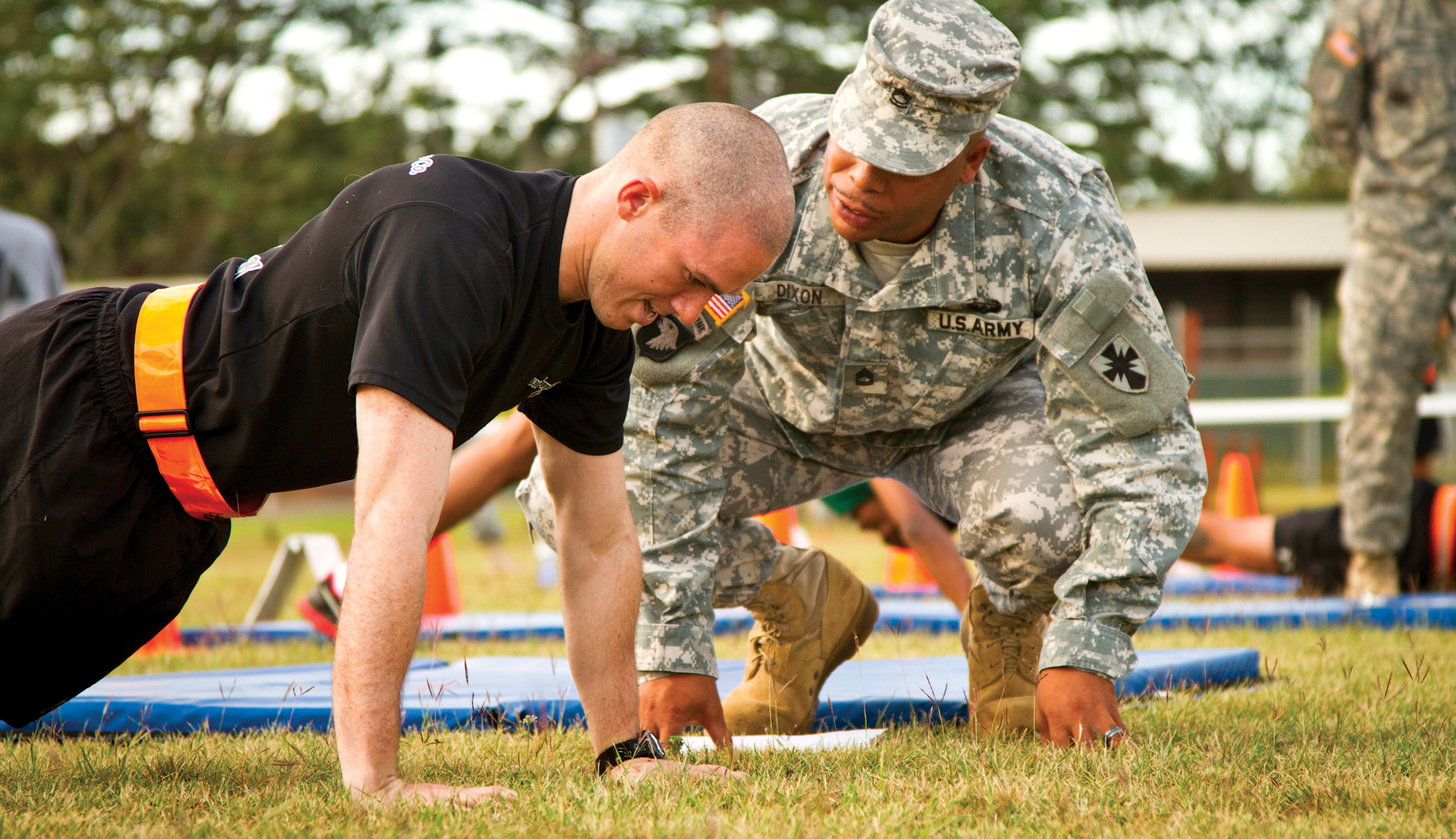

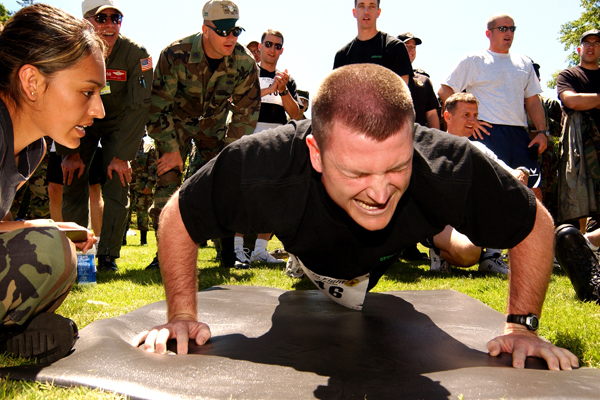

Press-ups in the Military

Press-ups are an integral part of military physical fitness and many military systems around the world train daily with this classic exercise. All branches of the British armed forces, Army, Royal Navy, Royal Air Force and Royal Marines, require press-ups on their physical fitness standard tests.

Linking to Burpees!

Royal Huddleston Burpee adapted the Front Leaning Rest (FLR) position by starting in the standing position, thus creating the Burpee.

The FLR is sometimes known as the press-up – although it is really the start position of a press-up.

Part Three: Performing A Press-up

Practical Tips

There are a number of practical tips that can be used to enhance performance and reduce the risk of injury.

There are a number of practical tips that can be used to enhance performance and reduce the risk of injury.

- Frequency: it is very important to allow your body time to recover from your daily workouts. Muscle tissue is broken down during exercise but will rebuild itself during periods of rest and recovery. Working the muscles on consecutive days will hamper the rebuilding process. Current convention suggests the body needs 48 hours to recover and adapt to the stress of strength training.

- Wrists Hurt: try closing your hands and making a fist to perform the press-ups. This way your body weight ends up on your knuckles instead of your palms, thus avoiding the wrist extension motion. Ensure that you do this type of press-up on a padded mat, plush carpet of even a folded towel.

- Chest to the Floor: good form should put your chest within an inch or two of the floor. There is no specific need to touch the floor with your chest, but aim to form a 90 degree angle at your elbow joint.

- Speed: press-ups should be performed in a slow, deliberate manner. Rather than bouncing up and down, it is important to maintain full control as you lower and raise your body. As a rough guide, each phase – both up and down – of a single press-up should take a couple of seconds.

- Breathing: it is important to breathe in during the descent and breathe out on the ascent. Make sure you do not hold your breath and make every effort to breathe rhythmically throughout the exercise.

- Head Alignment: your head should be held in a neutral position – this is, not looking forward, up or down at your navel. Looking slightly above your hands reduces the strain on your neck muscles.

- Elbows Hurt: at the top of the movement the arms should be almost straight, but be careful not to lock or snap them in place. Also, be sure to keep your elbows close to your body and not splayed out past your hands. If your form is good, you should feel a contraction in your triceps muscle.

- ‘Good’ Pain: can be the feeling of being ‘pumped’ as your muscles fill with blood during exercise, or it can be the mild feeling of fatigue as the lactic acid burn sets in. Recognise these sensations and learn to thrive on them.

- ‘Bad’ Pain: on the other hand, is any sharp pain or spasm, or pain that moves quickly into the shoulders, arms or hands – these are definite warning signs.

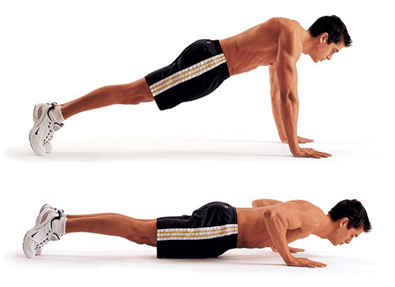

Performing a Press-up

To begin, assume a prone position on the floor or other surface that is able to support your body weight;

To begin, assume a prone position on the floor or other surface that is able to support your body weight;- Place your feet side by side with your toes curled towards your head so that the balls of your feet touch the ground;

- Place your hands on the floor approximately shoulder-width apart;

- Make sure your elbows do not flare out past your hands;

- Maintain a straight line from your shoulders to your feet by keeping your abs tights;

- Do not raise your butt in the air or allow your back to sag to the ground;

- Now, breathe in as you lower your torso to the ground, stopping when your elbows form a 90-degree angle and your chest is an inch or two from the ground;

- Keep your elbows close to your body for more resistance and keep your head in line with your body;

- Next, breathe out as you push yourself up using your arms;

- The power for the push will predominantly come from your shoulders and chest;

- You should also feel a contraction in your triceps;

- Continue the press-up until your arms are almost in a straight, but not locked, position;

- Repeat the raising and lowering action of the exercise until you reach your maximum, set or repetition limit.

Building-up to a Classic Press-up

For some people going straight into a classic press-up may be too much for a variety of reasons. However, there are exercises that can be used to prepare the mind and body for the classic press-up:

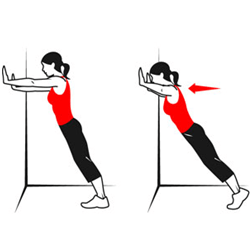

Wall press-up: the ‘wall’ press-up dramatically reduces the pressure on the arms, upper back and abs. The closer you stand to the wall, the easier it is to perform, but remember, it is still important to be aware of your body alignment as you perform this press-up.

Wall press-up: the ‘wall’ press-up dramatically reduces the pressure on the arms, upper back and abs. The closer you stand to the wall, the easier it is to perform, but remember, it is still important to be aware of your body alignment as you perform this press-up.- Counter/Table Press-up: Slightly more challenging than the wall press-up but still offering several degrees of assistance, the counter or table press-up is a very effective exercise that will target your upper back muscles and engage your triceps.

- Bench/Chair Press-up: For the next degree of difficulty, swap the table for a low bench or chair to support your arms while you perform regular press-ups. This type of press-up allows you to really concentrate on the press-up motion; all without the strain of the classic version.

- Knee Press-up: To reduce the lifting load by about 50%, you can modify the traditional press-up position by doing the exercise on your knees. Keeping a straight line from neck to torso is still important, pay attention to correct body alignment.

|

|

Population Averages

Table 2 highlights the population averages for males and females of selected age groups.

| Table 2: Male and female averages by age | ||

| Age | Male | Female |

| 20 | 44 | 26 |

| 25 | 39 | 23 |

| 30 | 34 | 21 |

| 35 | 30 | 18 |

| 40 | 27 | 16 |

| 45 | 24 | 13 |

| 50 | 21 | 11 |

| Source: Nieman, 1999 | ||

Part Four: Weight, Position, Animals & Record Breakers

How Much Weight is Lifted When Performing Press-ups?

In a study by Suprak et al. (2011) the amount of weight lifted during a press-up was researched. Twenty-eight subjects performed modified press-ups and full press-ups. Measurements were taken in the up position and the down position. Suprak et al. found that the following percentages of bodyweight were being exerted by the upper body during the press-up:

In a study by Suprak et al. (2011) the amount of weight lifted during a press-up was researched. Twenty-eight subjects performed modified press-ups and full press-ups. Measurements were taken in the up position and the down position. Suprak et al. found that the following percentages of bodyweight were being exerted by the upper body during the press-up:

- Up position (modified press-up): 53.56%

- Up position (full press-up): 69.16%

- Down position (modified press-up): 61.80%

- Down position (full press-up): 75.04%

Using the above information, the following could be concluded:

- For a 140-pound person doing a modified press-up, he or she would be lifting:

- Approximately 75 pounds of his/her bodyweight in the up position

- In the down position, he/she would be lifting approximately 86 pounds

- For a 190-pound person doing a full press-up, he or she would be lifting:

- Approximately 131 pounds of his/her bodyweight in the up position

- In the down position, he/she would be lifting approximately 142 pounds

Many individuals hold press-ups in the up position. But the information above indicates that one would be lifting more weight in the down position. As a result, you might try holding a press-up in the down position to offer more challenge in your press-ups.

Hand Position

Changing hand positions was explored by Cogley et al. (2005). These researchers looked at performing conventional press-ups with a narrow hand placement compared to shoulder width or wide hand placement. Results found that an increased number of muscles were activated in a press-up with a narrow hand placement compared to wide hand placement. However, completing press-ups like has an increased risk factor due to torque at the elbow.

In the Animal Kingdom

There are zoology observations that certain animals emulate a push up action. Most notably various taxa of the Fence lizard exhibit this display, primarily involving the male engaging in postures to attract the female. The Western fence lizard is a particular species that also engages in this behaviour (in Mexican Spanish push-ups are called ‘lagartijas’, which means ‘lizards’.).

Record Breakers and Attempts

The first record for push-ups was documented by Guinness World Records: 6,006 non-stop push-ups by Charles Linster in 1965, October 5.

The first record for push-ups was documented by Guinness World Records: 6,006 non-stop push-ups by Charles Linster in 1965, October 5.- The record for the most push-ups non-stop was 10,507, set by Minoru Yoshida of Japan in October 1980.

- Minoru Yoshida’s World Record was the last of its category for non-stop push-ups to be published by Guinness World Records. A new category, “Most Push-ups in 24 Hours,” has since been introduced.

- The current world record for most push-ups in 24 hours is by Charles Servizio (USA) who achieved 46,001 push-ups in just 21 hours, 6 minutes on 1993, April 24 to 25.

- The world record for most two-handed backhand push-ups in one hour is 1,940 by Aman Sharma of the UK, set in 2007. Doug Pruden (Canada) performed 1,025 one-arm push-ups on the back of the hand on 8 November 2008.

Other challenges and records include:

- Take the 22 Push Up Challenge for 22 days or more: https://activeheroes.org/22pushups/.

- Record Holders (an alternative to the GWR): http://www.recordholders.org/en/list/pushups.html.

- Guinness World Records (GWR): http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/most-push-ups-in-one-hour.

- Push Up Hall of Fame: https://www.facebook.com/TheOfficialPushUpHallOfFame.

- Paddy Doyle (former British Para): http://www.recordholders.org/en/records/doyle.html.

Part Five: Miscellaneous

Muscle Movement Classification

- Agonist:

- A muscle that causes motion.

- Antagonist:

- A muscle that can move the joint opposite to the movement produced by the agonist.

- Target:

- The primary muscle intended for exercise.

- Synergist:

- A muscle that assists another muscle to accomplish a movement.

- Stabiliser:

- A muscle that contracts with no significant movement to maintain a posture or fixate a joint.

- Dynamic Stabiliser:

- A bi-articulate muscle that simultaneously shortens at the target joint and lengthens at the adjacent joint with no appreciable difference in length.

- Dynamic stabilisation occurs during many compound movements.

- The dynamic stabiliser may assists in joint stabilisation by countering the rotator force of an agonist.

- Antagonist Stabiliser:

- A muscle that contracts to maintain the tension potential of a bi-articulate muscle at the adjacent joint.

- The antagonist stabiliser may be contracted throughout or at only one extreme of the movement.

- The antagonist stabiliser is activated during many isolated exercises when bi articulate muscles are utilised.

- The antagonist stabiliser may assist in joint stabilisation by countering the rotator force of an agonist.

- Antagonist Stabilisers also act to maintain postural alignment of joints, including the vertebral column and pelvis.

- For example, Rectus Abdominis and Obliques counters the Erector Spinae’s pull on spine during exercise like the Deadlift or Squat.

- This counter force prevents hyperextension of the spine, maintaining the tension potential of the Erector Spinae.

Forms of Muscle Contraction

- Isotonic:

- The contraction of a muscle with movement against a natural resistance.

- Isotonic actually means ‘same tension’, which is not the case with a muscle that changes in length and natural biomechanics that produce a dynamic resistance curve.

- This misnomer has prompted authors to propose alternative terms, such as dynamic tension or dynamic contraction.

- Isokinetic:

- The contraction of a muscle against concomitant force at a constant speed.

- Diagnostic strength equipment implements isokinetic tension to more accurately measure strength at varying joint angles.

- Concentric:

- The contraction of a muscle resulting in its shortening.

- Eccentric:

- The contraction of a muscle during its lengthening.

- Dynamic:

- The contractions of a muscle resulting in movement. Concentric and eccentric contractions are considered dynamic movements.

- Isometric:

- The contraction of a muscle without significant movement, it is also referred to as static tension.

Aerobic versus Anaerobic

- Aerobic:

- Requiring air, where air usually means oxygen.

- Aerobic exercise is usually prolonged exercise of of low- or moderate-intensity.

- For example, a five-mile run at 10-minute per mile pace.

- Anaerobic:

- Without air.

- Anaerobic exercise is usually short duration exercise of high-intensity.

- For example, a 100-metre sprint in 15 seconds.

Further Reading

Cogley, R.M., Archambault, T.A., Fibeger, J.F., Koverman, M.M., Youdas, J.W. & Hollman, J.H. (2005) Comparison of Muscle Activation Using various Hand Positions During the Push-up Exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 19, pp.628-633.

http://www.facebook.com/TheOfficialPushUpHallOfFame

http://www.recordholders.org/en/list/pushups.html

Nieman, D.C. (1999) Exercise Testing and Prescription: A Health Related Approach. 4th ed. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing.

Suprak, D.N., Dawes, J. & Stephenson, M.D. (2011) The Effect of Position on the Percentage of Body Mass Supported During Traditional and Modified Push-up Variants. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 25, pp.497-503.

2 thoughts on “The Classic Press-up”