| Elite & Special Forces Main Page | US Elite & Special Forces Main Page |

This article is structured as follows:

- Part 01: Background to the US Army Ranger School.

- Part 02: Entry Standards and Applications.

- Part 03: Outline of US Army Ranger School Selection and Training

- Part 04: Miscellaneous

PART ONE: BACKGROUND

1.0 Introduction

This article provides an overview of the recruitment, selection and training process for the United States (US) Army Rangers.

This article provides an overview of the recruitment, selection and training process for the United States (US) Army Rangers.

US Army Rangers, widely known as the Rangers, are Tier 1 forces (i.e. undertake direct action) and are trained by the US Army’s Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade located at the Manoeuvre Centre of Excellence in Fort Benning, Georgia.

These Army Commandos form the raider element of the US Army Special Operations Command (ARSOC or USASOC) Special Operations Forces (SOF) community, which is the land component of the US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM).

In 2014, 4,057 students attempted the notoriously difficult Ranger School, and only 1,609 earned the right to wear the Ranger Tab (Macias, 2015).

The two-month US Army Ranger School programme, founded in 1950, is a physically intensive training that aims to mold participants into elite military fighters. It takes place in the hills of Fort Benning, Georgia, and in the swamps of Florida, where trainees hone combat and leadership skills while learning how to survive with little sleep and food.

Ranger School is the Army’s premier combat leadership course, teaching students how to overcome fatigue, hunger and stress to lead soldiers in small-unit combat operations. It is separate from the 75th Ranger Regiment. Soldiers who have earned Ranger Tabs, male or female, are not automatically part of the 75th Ranger Regiment, which has its own requirements and assessment process.

It must be emphasised that a candidate must be physically fit at the beginning of the US Army’s Ranger training process if they are to stand any chance of success. The course requires far greater expenditure of physical energy than is normally required in other peace time training. It is essential that candidates arrive fully fit, carrying no injuries and with a sound grasp of basic navigational techniques.

1.1 Aim

The aim of this article is to describe the fundamental entry requirements, selection process and training for personnel seeking to become a qualified US Army Ranger.

For information regarding the 75th Ranger Regiment’s Ranger Assessment & Selection Programme (RASP) look here.

1.2 Women and the US Army’s Rangers

It was announced in June 2013 that women may begin to train in some of the most elite units of the US military, with women being able to start training as US Army Rangers by July 2015 (O’Toole, 2013).

In September 2014, the US Army started accepting applications from women for US Army Ranger training (Thomas, 2014), although a final decision on them undertaking the actual training (on an experimental basis) was reserved till January 2015.

Between January and April 2015, successful female applicants were required to attend the US Army National Guard’s 2-week Ranger Training Assessment Course (RTAC, Section 3.3.2) in preparation for their April assessment (Tan, 2015a). Table 1 provides an outline of the number of men and women who started and successfully completed each iteration of the RTAC.

| Table 1: RTAC pass rate for men and women | ||||||

| RTAC Iteration | Total Started | Men Started | Women Started | Total Passed | Men Passed | Women Passed |

| January 2015 | 122 | 96 | 26 | 58 | 53 | 5 |

| February 2015 | 100 | 83 | 17 | 36 | 35 | 1 |

| March 2015 | 119 | 85 | 34 | 31 | 25 | 6 |

| April 2015 | 139 | 78 | 61 | 38 | 30 | 8 |

| Totals | 480 (100%) | 342/480 (71%) | 138/480 (29%) | 163/480 (34%) | 143/163 (88%) | 20/163 (12%) |

| Source: Tan, 2015a | ||||||

On 20 April 2015, 19 women and 381 men (Alexander, 2015; Tan, 2015b), 20 women and 380 men (Keating, 2015; Macias, 2015), started a gender-integrated assessment of the US Army’s Ranger course.

In brief, the course progressed as follows (Tan, 2015a; 2015b):

- Eight of the nineteen women made it through the Ranger Assessment Phase, known as RAP week.

- Zero of the eight women successfully completed the First Phase on the first try. They were recycled (back-squadded in the UK vernacular) along with 101 of their male colleagues.

- After a second attempt at the First Phase, three women (who accepted) and two men (who declined) were given the option of a Day One recycle (a normal course procedure that is used when students struggle with one aspect of the course and excel at others).

- Two of the women successfully completed the First Phase at the third attempt, and both had one attempt each at the Second and Third Phases (which they successfully completed).

- The third woman had at the time of reporting (Tan, 2015a; Yuhas, 2015) completed three attempts at First Phase and two attempts at Second Phase. It was then reported that she had progressed to Third Phase (Tan, 2015b).

- The final result of the course was 2 women and 94 men graduating (Alexander, 2015) or 2 women and 381 men graduating (Keating, 2015).

Consequently, on 21 August 2015, Captain (OF-2) Kristen Griest and 1st Lieutenant (OF-1) Shaye Haver, aged 26 and 25 respectively, became the first female graduates of the US Army’s Ranger course (Tan, 2015b; Yuhas, 2015).

Consequently, on 21 August 2015, Captain (OF-2) Kristen Griest and 1st Lieutenant (OF-1) Shaye Haver, aged 26 and 25 respectively, became the first female graduates of the US Army’s Ranger course (Tan, 2015b; Yuhas, 2015).

On 16 October 2015, Major (OF-3) Lisa Jaster became the third woman, and first female US Army Reserve officer, to successfully complete the US Army’s Ranger training (Tan, 2015c). Jaster, who was 37 at the time, graduated with 87 of her male colleagues.

While the three female graduates would be allowed to wear the Ranger tab on their uniforms, which signifies completion of the programme, they remained barred from other military opportunities open to men. US Army officials said the women would not able to apply to the US Army’s 75th Ranger Regiment (with its own unique set of physical requirements and assessment process) or serve in infantry or front-line combat positions, which are usual career paths for graduates of the Ranger programme (Fang, 2015).

On 02 September 2015, the US Army announced that Ranger training was “now open to all qualified soldiers regardless of gender…” (Tan, 2015b).

From January 2016, in accordance with current US Federal Government policy on the employment of women in the US military, service in the US Army’s Rangers (including the positions noted above) is open to both male and female volunteers (Pellerin, 2015).

Women in the US military have, for a number of years, been able to serve in a variety of SOF-related roles, including:

- Intelligence;

- Military information support;

- Civil affairs units;

- Female engagement teams;

- Cultural support teams; and

- Air Force special operations aviation roles.

As of March 2015, approximately two-thirds of the roles in USSOCOM were integrated (Vogel, 2015).

On 30 August 2019, US Air Force 1st Lieutenant Chelsey Hibsch became the first female airman to earn the Ranger tab (Correll, 2019).

Hibsch was eligible to take the Army Ranger Course after she attended the Air Force’s Ranger Assessment Course, which is hosted by the Air Force Security Forces Centre and based on the first two weeks of the Army Ranger Course.

US Army Staff Sergeant Amanda Kelly became the first female enlisted soldier to graduate Ranger School in August 2018 (Correll, 2019).

1.3 Factors for Increasing the Likelihood of Success

I will leave it to the Command Sergeant Major (as at 24 February 2016) of the Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade, in his welcome letter, to state that:

I will leave it to the Command Sergeant Major (as at 24 February 2016) of the Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade, in his welcome letter, to state that:

“Students must be mentally and physically fit when reporting. The standards for Ranger School are well known and available on the website. You are expected to show up physically capable of achieving those standards. The three events that cause the most students to recycle or fail Ranger School are the Ranger Physical Assessment, the land navigation test, and the foot march. You must train for the cumulative effects of RAP Week. Success in those events significantly increases your chance of graduating. Do not rely on adrenaline to overcome a shortcoming in your fitness level.”

Between 2000 and 2012, approximately 51% of candidates failed the Ranger course, with approximately 29% failing RAP week (Section 3.4.1). During FY15, approximately 31% of candidates recycled at least one phase of Ranger training (with 62% of recycles being due to patrols).

“One of the best ways to become familiarized with the course conditions is to attend a unit-level pre-Ranger class. If a unit-level course is not available, the National Guard’s Warrior Training Center offers the Ranger Training and Assessment Course (RTAC) at Fort Benning.” (Kearnes, 2015, p.40-41).

Four attributes to master:

- Physical fitness;

- Technical/tactical proficiency;

- Mental toughness; and

- Winning spirit, never quit.

1.4 Brief History

Ranger Training began in September 1950 at Fort Benning, Georgia, with the formation and training of 17 Airborne Ranger companies during the Korean War, under the aegis of the Ranger Training Command.

In October 1951, the Commandant of the US Army Infantry School established the Ranger Department and extended Ranger Training to all combat units in the US Army.

Under the Ranger Department, the first Ranger School Class was conducted between January and March 1952, with a graduation date of 01 March 1952 and was 59-days in duration. At the time, Ranger training was voluntary.

From 1954 to the early 1970’s, the US Army’s goal, though seldom achieved, was to have one Ranger qualified non-commissioned officer (NCO) per infantry platoon and one officer per company. In an effort to better achieve this goal, in 1954, the Army required all combat arms officers to become Ranger/Airborne qualified.

On 01 November 1987, the Ranger Department reorganised into the Ranger Training Brigade, and established four Ranger Training Battalions, three of which still delivering training.

The Ranger course has changed little since its inception; until recently it was an 8-week course divided into three phases: known as crawl, walk and run. The course is now 60 to 62-days in duration and remains divided into three phases, known as Benning, Mountain and Florida.

1.5 US Army Ranger Beret

In June 2001, Army Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki gave the order to issue black berets to Regular Army soldiers, which had previously been worn exclusively by the 75th Ranger Regiment since 1979 (Shaughnessy, 2011).

The Rangers did not have Presidential authorisation for the exclusive wearing of the black beret and, subsequently, the Rangers switched to wearing a tan beret to preserve a unique appearance. The tan colour was chosen to reflect the buckskin worn by the men of Robert Roger’s Rangers during the French and Indian War (Bahmanyar, 2011).

A memorandum for the purpose of changing the ranger beret from black to tan was sent and approved in March 2001. In a private ceremony, past and present Rangers donned the tan beret on 26 July 2001.

It must be noted that only Rangers who serve with the 75th Ranger Regiment wear the tan beret.

1.6 US Army Ranger School and the 75th Ranger Regiment

Successful completion of Ranger School and earning the Ranger Tab does not guarantee a job with the 75th Ranger Regiment, or one of its Battalions.

Successful completion of Ranger School and earning the Ranger Tab does not guarantee a job with the 75th Ranger Regiment, or one of its Battalions.

To apply for service with the 75th Ranger Regiment candidates must have a valid Military Occupational Speciality (MOS), of which there are approximately 100 (60 for enlisted, 16 for Warrant Officers and 25 for Officers), as well as successfully complete one of two programmes:

- Ranger Assessment Selection Programme (RASP) 1: an 8-week course for candidates in the rank of Private to Sergeant.

- Ranger Assessment Selection Programme (RASP) 2: a 21-day course for candidates in the rank of Staff Sergeant and above.

Part of the reason for allowing all personnel a chance at Ranger training is osmosis, i.e. the natural spread of attitude, skills and knowledge across the wider-US military.

For example, the US Naval Special Warfare Command (NSWC) and Marine Special Operations Command (MARSOC) send personnel to Ranger School after having completed their respective Special Forces training courses. Why, given their level of training, would US Navy SEALs and Critical Skills Operators then need to attend Ranger training? Because it adds value to their roles.

The Royal Marines adopt a similar policy for the All Arms Commando Course (AACC), the first woman to pass the AACC never actually served with a Commando unit, and the second was a Royal Navy Doctor.

There are essentially two types of Ranger (although some will argue one type is a Ranger and the other is Ranger Qualified):

- US Army soldiers who complete RASP 1 or 2 and Ranger School who will then serve with the 75th Ranger Regiment; and

- US and foreign military personnel who complete Ranger School and return to their original unit.

PART TWO: ENTRY STANDARDS AND APPLICATIONS

Information regarding the basic requirements for enlistment or commissioning in the US Army can be found by clicking on the links, which the reader is advised to read if not already familiar.

The US Army does not accept direct entry applicants, i.e. civilians with no prior military experience, for Ranger training. As a result, volunteers for the US Army’s Ranger training may be accepted from US military personnel (both officer and enlisted) from any branch of military service to qualify as a Ranger.

Consequently, there are three recognised pathways to becoming a qualified Ranger:

- Apply as an Active Duty candidate from any US branch of military service;

- Apply as a Reserve candidate from any US branch of military service; or

- Apply as a candidate from a foreign military service.

2.0 General Requirements and Eligibility for All Candidates

Subject to the requirements outlined below, all officers and enlisted (other ranks) personnel from the US Marine Corps, US Navy, US Air Force and US Army are eligible to attend Ranger training.

Subject to the requirements outlined below, all officers and enlisted (other ranks) personnel from the US Marine Corps, US Navy, US Air Force and US Army are eligible to attend Ranger training.

However, the two largest groups of candidates for Ranger School are the US Army’s Infantry Basic Officer Leadership Course (IBOLC) and the 75th Ranger Regiment. The US Air Force is allocated six slots each year for its candidates (Hammes, 2014).

General Requirements for all candidates:

- Common Task List: Commanders must certify their candidate on the 26 Ranger Common Tasks within 90 days of the candidate reporting to Ranger School. Ranger candidates not certified by their sending unit commander, or failing to provide a memorandum of certification will not be admitted to the Ranger Course.

- Hot/Cold Weather Injuries:

- Previous Hot Weather Injuries are precluded from attending classes between April-October.

- Previous Cold Weather Injuries are precluded from attending Ranger classes between October-April.

- Medical Standards:

- Candidates who do not meet medical fitness standards IAW AR 40-501, chapters 2 and 5-3 may request waiver consideration from the ARTB Physician Assistant.

- DD 2801-1 (Report of Medical History) and DO 2808 (Report of Medical Examination), complete, signed by a Physician (MD or DO), dated within 18 months of the reporting date for attendance at Ranger School.

- Medical conditions that are disqualifying for admittance into the Ranger Course are those requiring the use of chronic medications or regular surveillance, conditions that are on-going without resolution, or any condition that would make the candidate non-deployable IAW AR 40-501.

- Commander’s Validation Letter: Candidates must have a copy of the commander’s validation letter.

- Ranger School Task Proficiency Checklist: Candidates must have a copy of the Task Proficiency check list signed off by their commander.

2.1 General Requirements and Eligibility for Enlisted Candidates

Enlisted applicants must have a standard General Technical (GT) score of 90 or higher in aptitude and 12 months or more Active Duty service remaining after the completion of the course IAW AR 614-200.

Ranger training is available on a voluntary basis only for enlisted soldiers who are E-3 and above.

2.2 General Requirements and Eligibility for Officer Candidates

No additional active duty service obligation (ADSO) is incurred by Active Army commissioned officers for attending the Ranger Course.

2.3 Candidates from another Branch of Military Service

The US Army allocates a select number of training slots each year to other US branches of military service, including their Reserve components, as well as foreign military services.

The US Army allocates a select number of training slots each year to other US branches of military service, including their Reserve components, as well as foreign military services.

These highly valued school slots are often competed for and used to augment the training of specialised combat career fields that directly support US Army units.

Upon completion of the Ranger course, all personnel return to the units that sent them and are referred to as being ‘Ranger Qualified’.

In order to attend Ranger training a candidate must have a graduation diploma from an Air Force or Army:

- Pre-Ranger Course (Section 3.3.1);

- Small Unit Ranger Tactics Course;

- Ranger Assessment Course (Section 3.3.1); or

- Ranger Training Assessment Course (Section 3.3.2).

It is not uncommon for US Navy SEALs, Joint Tactical Air Controllers (JTACs), and US Marine Force Recon and Marine Special Operations Command (MARSOC) personnel to attend Ranger training.

2.4 Airborne Qualified Candidates

Candidates are not required to be Airborne qualified, but are encouraged to attend the Basic Airborne Course (scroll down to Section 3.2) prior to attending the Ranger course.

75th Ranger Regiment candidates will typically complete the Basic Airborne Course prior to attendance at the Ranger School.

2.5 US Army National Guard Candidates

All US Army National Guard candidates are required to successfully complete the Ranger Training Assessment Course (Section 3.3.2) in order to progress on to Ranger School.

PART THREE: OULTINE OF US ARMY RANGER SCHOOL SELECTION AND TRAINING

3.0 US Army Ranger School Selection and Training Phases

The journey to becoming Ranger Qualified is not easy, with training being rigorous and highly selective. Approximately 4,000 candidates will attend training each year but, on average, only 50% will be successful.

The journey to becoming Ranger Qualified is not easy, with training being rigorous and highly selective. Approximately 4,000 candidates will attend training each year but, on average, only 50% will be successful.

The 62-day US Army Ranger course is the training pipeline for candidates wishing to join the US Army’s Ranger community.

All Ranger candidates will undertake a number of distinct phases of training (Table 2), in which candidates are taught the fundamentals of Ranger warfare through formal US Army schooling, known as Ranger School.

Ranger School consists of three phases: Benning, which lasts 21 days and includes water survival, land navigation, a 12-mile march, patrols, and an obstacle course; Mountain Phase, which lasts 21 days, and includes assaults, ambushes, mountaineering and patrols; and Swamp Phase, which lasts 17 days and covers waterborne operations. On average, training days last for 19 hours, seven days a week.

| Table 2: US Army Ranger training pipeline | ||||||

| Serial | Phase | Regular Army | National Guard | Duration | ||

| 1 | 0 | Unit-Level Pre-Ranger Class or RTAC | Ranger Training Assessment Course | 2-weeks | ||

| 2 | I to III | Start of Ranger School | 62-days | |||

| 3 | I | First Phase (Benning Phase) | 21-days | |||

| 4 | Ia | Part 1: Ranger Assessment Phase | 4-days | |||

| 5 | Ib | Part 2: Patrol Phase (or Darby Phase) | 17-days | |||

| 6 | II | Second Phase (Mountain Phase) | 21-days | |||

| 7 | III | Third Phase (Florida Phase or Swamp Phase) | 17-days | |||

| 8 | IIIa | Graduation and Out-processing | 3-days | |||

3.1 Training Hierarchy

The US Army’s Manoeuvre Centre of Excellence (MCoE) is the home of the US Army’s Infantry School, commanded by a Major General (OF-7) and Brigadier General (OF-6) respectively, and located at Fort Benning in Georgia.

The US Army’s Manoeuvre Centre of Excellence (MCoE) is the home of the US Army’s Infantry School, commanded by a Major General (OF-7) and Brigadier General (OF-6) respectively, and located at Fort Benning in Georgia.

The Infantry School is, in turn, home to the Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade (ARTB), commanded by a Colonel (OF-5).

Besides Ranger training, the ARTB also provides airborne, jumpmaster and pathfinder courses for the US Army. As part of its Ranger remit, the ARTB conducts the Ranger course in order to produce Rangers to fill:

- U (75th Ranger Regiment);

- V (Airborne Ranger); and

- G (Non-Airborne Qualified Ranger) coded positions.

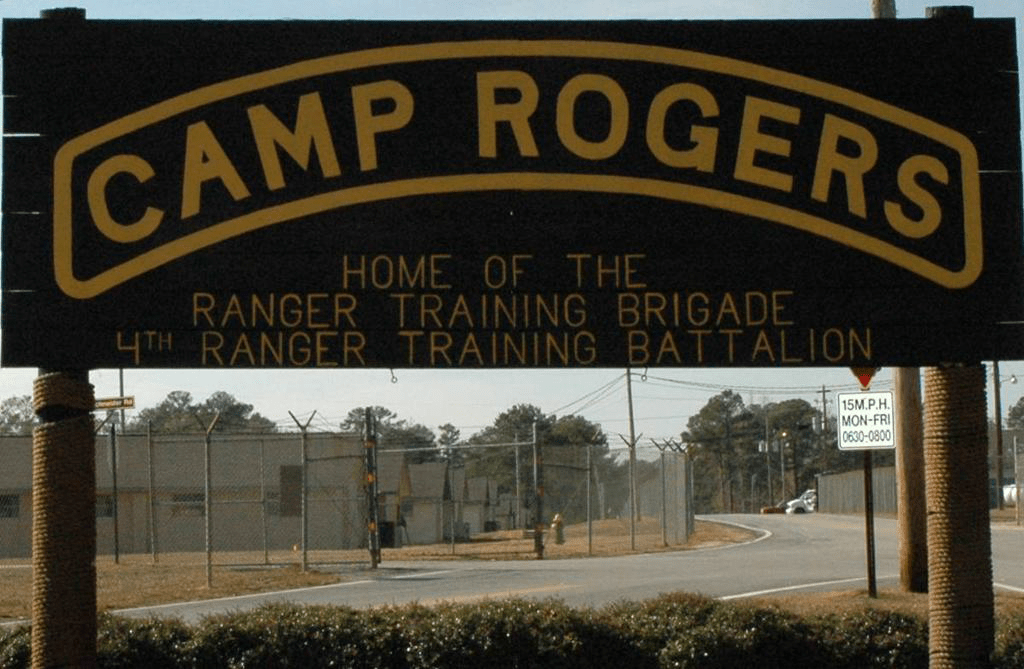

The ARTB delivers Ranger training through three Ranger Training Battalions, each commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel (OF-4):

- 4th Ranger Training Battalion: Conducts First Phase of Ranger training.

- 5th Ranger Training Battalion: Conducts Second Phase of Ranger training.

- 6th Ranger Training Battalion: Conducts Third Phase of Ranger training.

3.2 Ranger Instructors and Platoon Tactical Trainers

Members of the Ranger Training Companies are all Ranger Instructors (RIs), also known as Lane Graders, or Platoon Tactical Trainers (PTTs) and undergo a rigorous certification process before becoming instructors.

Members of the Ranger Training Companies are all Ranger Instructors (RIs), also known as Lane Graders, or Platoon Tactical Trainers (PTTs) and undergo a rigorous certification process before becoming instructors.

All RIs and PTTs must successfully complete a Ranger Physical Assessment (Table 3 below), as well as a height and weight evaluation.

RIs will undertake a 30-90 day Ranger Instructor Certification Programme (RICP), which is performance orientated training, typically supervised by the Command Sergeant Major (CSM). Training may include:

- Instructor Training Course;

- Tactics Certification Course;

- Certification Boards;

- Combat Life Saver/Ranger First Responder Certification;

- Army Physical Fitness Test, 5-mile run and 12-mile loaded march to standard;

- Collateral Safety Officer Course;

- Risk Management Process;

- Environmental and Camp specific Risk Management Worksheets;

- Demolitions Effects Simulator Training;

- Medical Evacuation/SKEDCO Litter and Hoist Training;

- Special Skills Training (e.g., Assault Climber Course, Summer Mountaineering Course);

- Observation Patrol, aka ‘Shadow Walks’;

- Practice Patrol: Practice Evaluation; and

- Patrol: Evaluation as a Patrol Grader.

A PTT undergoes a 60-90 day certification process and becomes a fully certified Ranger Instructor, and:

- Is responsible for the conduct of training for a Ranger Training Platoon;

- Will ensure quality control of doctrinal training and enforce safety standards;

- Will teach blocks of instruction;

- Will Counsel and evaluate Ranger Instructors and students; and

- Will have additional responsibilities (unit specific).

There is an approximate ratio of 9:1 of students to instructors.

In 2015, Staff Sergeant “Manuel Quggiotto, with the 4th Alpine Italian Ranger Battalion, proved himself when he began the U.S. Army Ranger Course April 20 and graduated July 10. Now, he is training to become a Ranger instructor for the 5th Ranger Training Battalion in Dahlonega, Georgia, as part of the Italian Ranger Reciprocal Exchange Position program.” (Wiehe, 2015).

3.3 Ranger Preparation Courses

Besides personal training, there are two forms of structured preparation training that candidates may undertake:

- Unit-Level Pre-Ranger Class; and

- The Ranger Training Assessment Course.

3.3.1 Unit-Level Pre-Ranger Class

A Unit-Level Pre-Ranger Class can also be known as a Pre-Ranger Programme (PRP), Pre-Ranger Course (PRC) or Ranger Assessment Course (RAC).

A Unit-Level Pre-Ranger Class can also be known as a Pre-Ranger Programme (PRP), Pre-Ranger Course (PRC) or Ranger Assessment Course (RAC).

Although the precise structure of Pre-Ranger training varies between units, there are common elements such as the Ranger Physical Assessment, Combat Water Survival Assessment and the 12-mile loaded march (view Section 3.4.1).

For example, back in 2012, the 25th Infantry Division conducted a 5-day PRP, delivered every month, which followed the first week of Ranger School training (Sallette, 2012). The PRP catered for 15-30 candidates and was divided into two phases:

- Phase 1: Ranger Physical Assessment (see Table 3 below) and training on how to write warning orders, operation orders, build terrain models and conduct battle drills.

- Phase 2: Field training exercise to demonstrate skills and knowledge learned during phase 1.

The PRP became one of several training courses delivered by the new Lightning Academy formed in 2013 (Cary, 2013).

US Air Force candidates undertake the 2-week Ranger Assessment Course (RAC) which was delivered at Silver Flag Alpha Range, Creech Air Force Base, in Nevada (1980 to 2014) (Clausen, 2014). 35% to 50% completed the course, with approximately 80% of these successfully completing Ranger School and earning their Ranger Tab.

“Since 1950, barely 300 Airmen have been Ranger qualified.” (Clausen, 2014), 257 according to Chris McCann (2014), a little over 300 says Callaghan (2014), and 263 states Hammes (2014).

A recent change to Air Force Instruction 36-2903 (Dress and Personal Appearance) means Ranger-qualified Airmen/Airwomen may now wear the Ranger Tab on their uniforms.

3.3.2 Ranger Training Assessment Course

The US Army National Guard (ARNG) Warrior Training Centre (WTC) is located at Fort Benning, Georgia. The WTC is commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel (OF-4), who is assisted by a Command Sergeant Major (OR-9).

Alpha Company, one of three training companies, delivers the Ranger Training Assessment Course (RTAC), as well as the Master Fitness Trainer and Basic Combatives I and II courses. Alpha Company is commanded by a Captain (OF-2), who is assisted by a First Sergeant (OR-8).

The RTAC is designed to assess whether a candidate could (successfully) attempt Ranger training. The RTAC is 16-days in duration and divided into two week-long phases (Acton, 2015; Tan, 2015a):

- Phase 1: is the Ranger Assessment Phase in which candidates are trained and evaluated on multiple tasks and techniques as identified in Table 3 below. Candidates are also trained in troop leading procedures, tactics, patrolling techniques, and small unit operations. Candidates must pass Phase 1 to progress on to Phase 2.

- Phase 2: is the Patrolling Phase during which candidates are rotated into leadership positions and evaluated on their abilities to successfully accomplish small unit combat operations from planning through execution. Candidates are evaluated on their ability to lead squad sized patrols. Candidates who successful complete RTAC will be recommended for attendance on the Ranger Course. US Army National Guard Soldiers are required to successfully complete RTAC in order to attend the Ranger Course.

Candidates report for training on the Friday, with training starting on the Saturday. Candidates not from the 75th Ranger Regiment or the Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade must be in the Rank of PFC/E-3 or above to attend the RTAC; although a waiver may be gained from the WTC Commander. Every RTAC is observed by an instructor from the 4th Ranger Training Battalion (Section 3.4).

In the mid-1990s approximately 1 in 10 ARNG candidates successfully completed Ranger School (Acton, 2015). As a consequence of this poor record two Ranger School Instructors, 1st Lieutenant Jamison Kirby and Sergeant First Class Thomas Siter, began delivering an innovative preparation course in the late-1990s to ARNG candidates.

Although it took a number of years for the WTC to be officially established, it has since “…grown into a go-to source of specialized training for troops across the U.S. military.” (Acton, 2015).

In 2004, the RTAC found its current home at Camp Butler, Fort Benning, and in 2006 the WTC was officially named (Action, 2015).

Once a candidate successfully completes the RTAC they will be eligible to attend Ranger training.

3.4 Ranger School: First Phase

The First Phase of Ranger School is delivered by the 4th Ranger Training Battalion (4RTB) located at Fort Benning in Georgia. 4RTG is commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel (OF-4), who is assisted by a Command Sergeant Major (OR-9).

The First Phase of Ranger School is delivered by the 4th Ranger Training Battalion (4RTB) located at Fort Benning in Georgia. 4RTG is commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel (OF-4), who is assisted by a Command Sergeant Major (OR-9).

The First Phase of Ranger School is approximately 21-days in duration and is known as the Benning Phase, previously Crawl Phase. With a maximum class size of 405, on average 366 candidates will start Ranger School, with typically 11 courses each year.

4RTB consists of five companies, each commanded by a Captain (OF-2), three of which are Ranger Training Companies (Alpha, Bravo & Charlie) whose primary mission is to train Ranger candidates in a variety of subjects, including: physical readiness; land navigation; combatives; demolitions; airborne and helicopter insertion; and squad combat patrols.

During the Benning Phase, candidates receive training on squad operations and focus on ambush and reconnaissance missions, patrol base operations, and planning before moving on to platoon operations.

During the Benning Phase, candidates receive training on squad operations and focus on ambush and reconnaissance missions, patrol base operations, and planning before moving on to platoon operations.

The purpose of this phase of training is to develop and assess a candidate’s ability, as a member and leader, in small unit operations in close combat, through:

- Military skills;

- Physical stamina;

- Mental endurance (toughness); and

- Personal confidence.

The Benning Phase is delivered in two distinct parts:

- Part 1: Ranger Assessment Phase, also known as RAP week (established in 1992).

- Part 2: Patrol Phase: also known as the Darby Phase.

3.4.1 Part 1: Ranger Assessment Phase

Part 1 of the Benning Phase is known as the Ranger Assessment Phase or RAP Week, and is 4-days in duration. Table 3 provides an outline of RAP week.

| Table 3: Outline of RAP week | ||||||

| Day | Description | |||||

| 1 |

|

|||||

| 2 |

|

|||||

| 3 |

|

|||||

| 4 |

|

|||||

“The most significant stressor in the first week of Ranger School is the tempo of events. Performed individually, each task is easily attainable, but when combined with little sleep and restricted food over a period of 80 hours, they become much more difficult.” (Kearnes, 2015, p.41).

Between 2000 and 2012, approximately 29% of candidates failed RAP week. Of the two-thirds who progress to Part 2 of the Benning Phase, approximately 65% will graduate from Ranger School.

3.4.2 Part 2: Patrol Phase

Part 2 of the Benning Phase is known as the Patrol Phase or Darby Phase, and is 17-days in duration.

Part 2 of the Benning Phase is known as the Patrol Phase or Darby Phase, and is 17-days in duration.

During this part of the Benning Phase, candidates will undertake instruction in:

- Troop leading procedures;

- Principles of patrolling;

- Demolitions;

- Field craft; and

- Basic battle drills, focused on squad ambush and reconnaissance missions.

Before candidates begin practical application on what they have learned, they will negotiate the Darby Queen Obstacle course, consisting of 20 obstacles stretched over one mile of uneven hilly terrain.

Upon completion of the Darby Queen Obstacle course, candidates conduct three days of non-graded, squad-level patrols, one of which is entirely cadre led. After the last non-graded patrol day, students conduct two days of graded patrols, one airborne operation, and four more days of graded patrols.

However, before moving on to the Second Phase of Ranger School, candidates must have demonstrated their ability to plan, prepare, resource and execute a combat patrol as a squad or team leader. A combination of instructor and peer evaluation is utilised to demonstrate competence.

Simply put, the Benning Phase establishes the tactical fundamentals required for the Second and Third Phases of training.

On average, only 50% of candidates will successfully complete this phase of training.

3.5 Ranger School: Second Phase

The Second Phase of Ranger School is delivered by the 5th Ranger Training Battalion (5RTB) located at Camp Frank D. Merrill (Dahlonega) in the Northern Georgia Mountains. 5RTB is commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel (OF-4), who is assisted by a Command Sergeant Major (OR-9).

The Second Phase of Ranger School is delivered by the 5th Ranger Training Battalion (5RTB) located at Camp Frank D. Merrill (Dahlonega) in the Northern Georgia Mountains. 5RTB is commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel (OF-4), who is assisted by a Command Sergeant Major (OR-9).

5RTB consists of HHC, Alpha, Bravo and Charlie Companies, each commanded by a Captain (OF-2), who is assisted by a First Sergeant (OR-8).

The Second Phase of Ranger School is 20/21-days in duration and is known as the Mountain Phase, previously Walk Phase.

The purpose of this phase of training is to develop military mountaineering and mobility skills, as well as techniques for employing a platoon for continuous combat patrol operations in a mountainous environment. Training involves:

Developing mountaineering skills through a four day package:

Developing mountaineering skills through a four day package:

- Two days learning knots, belays, anchor points, rope management and the fundamentals of climbing and rappelling.

- Two day exercise at Yonah Mountain applying the skills learnt during the previous two days: day one, climbing and rappelling over exposed, high-angle terrain concluding with a 200 foot night rappel utilising night vision goggles; and day two, squad-level mobility training manifesting as movement of personnel, equipment, and simulated casualties through severely restrictive terrain using fixed ropes and hauling systems.

- Developing combat techniques through a four day package:

- Candidates receive instruction, and perform practical exercises, on movement to contact, patrol base, troop leading procedures, operations orders, combative, ambush and raid

- Developing patrolling techniques through two field training exercises over ten days, combat patrol missions:

- Are directed against a conventionally equipped threat force in a low intensity conflict scenario.

- Are conducted both day and night and include Air Assault operations and extensive cross country movements through mountainous terrain.

- Include movements to contact, vehicle and personnel ambushes, and raids on communication and mortar sites.

- Include river crossings and scaling steeply sloped mountains.

Candidates further develop their ability to command and control platoon-sized patrols through planning, preparing and executing a variety of combat patrol missions. Candidates will be challenged by the adverse conditions (e.g. rugged terrain, severe weather, hunger, mental and physical fatigue, and the emotional stress) of the mountains witnessed during this phase of training.

Successful candidates of the Mountain Phase will move by bus or parachute assault into the Third Phase of Ranger School.

3.6 Ranger School: Third Phase

The Third Phase of Ranger School is delivered by the 6th Ranger Training Battalion (6RTB) located at Camp James E. Rudder, near Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. 6RTB is commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel (OF-4), who is assisted by a Command Sergeant Major (OR-9).

The Third Phase of Ranger School is delivered by the 6th Ranger Training Battalion (6RTB) located at Camp James E. Rudder, near Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. 6RTB is commanded by a Lieutenant Colonel (OF-4), who is assisted by a Command Sergeant Major (OR-9).

6RTB consists of HHC, Alpha, Bravo and Charlie Companies, each commanded by a Captain (OF-2), who is assisted by a First Sergeant (OR-8).

The Third Phase of Ranger School is 17/18-days in duration and is known as the Florida Phase or Swamp Phase, previously Run Phase. This final phase of Ranger School is conducted in the coastal swamp around Camp Rudder (near Valparaiso (Tan, 2015b)), training approximately 2,500 candidates each year.

The purpose of this phase of training is to further develop a candidate’s combat arms functional skills, and consists of:

- 4-days of waterborne operations, small boat movements and stream crossings.

- Practical exercises in extended platoon-level operations executed in a coastal swamp environment to test the candidates’ ability to operate effectively under conditions of extreme mental and physical stress.

- Further development of the candidates’ ability to plan and lead small-units during independent and coordinated airborne (two jumps for airborne qualified personnel), air assault, small boat, and dismounted combat patrol operations in a low-intensity combat environment against a well-trained, sophisticated enemy.

- Ten days of patrolling during two field exercises designed to evaluate candidates on their ability to apply small unit tactics and techniques during the execution of raids, ambushes, movements to contact, and urban assaults to accomplish their assigned missions.

3.7 Ranger Recycling

(Yuhas, 2015) Applicants who fail one test but perform well in others can ‘recycle’ through those segments of a course, a second chance but also several additional weeks of laborious mental and physical exertion.

Some candidates will successfully complete Range School on their first attempt. Approximately two out of five initial candidates will graduate from Ranger School, with a third recycling through at least one phase.

3.8 Ranger Graduation

The final two days at the end of the course are used for out processing and graduation.

Most Ranger graduations occur on a Friday at Hurley Hill Training Area, overlooking Victory Pond, typically starting at 1100 hours and lasting 45 minutes.

After watching the Rangers in Action demonstration (1000 hours), friends, family, and fellow Rangers can assist in pinning the coveted black and gold Ranger tabs on the US military’s newest Ranger qualified personnel.

PART FOUR: MISCELLANEOUS

4.0 Summary

US Army Ranger training is open to all male and female officers and enlisted personnel of the US military. US Army Ranger training seeks to attract determined, highly-motivated, intelligent, reliable and physically fit individuals to serve with the US Army’s Ranger Battalions and more generally across the US military. This article provides the basic information to allow individuals to make an informed judgement before applying for US Army Ranger training.

4.1 TV Documentaries

- First aired in September 2001, ‘Army Ranger School’ was 50 minute documentary produced for the History Channel which followed class 10-00 through the three rigorous phases of the US Army’s Ranger School.

- First aired in August 2010, ‘Surviving the Cut’ was a two series (2010-2011) documentary produced for the Discovery Channel which took a behind the scenes look at the US military’s training process for its elite and special forces. Series 1, Episode 1 titled ‘Ranger School’ looked at the training undertaken by candidates attending the US Army’s Ranger School.

- First aired in July 2012, ‘Hell and Back: Special Ops Ranger’ was a 1-hour documentary produced for the Discovery Channel which, for the first time, took a look at the special operations training course of the 75th Ranger Regiment known as the Ranger Assessment and Selection Programme (RASP).

4.2 Useful Books, Documents and Magazines

- AR 40-501 – Standards of Medical Fitness: http://www.apd.army.mil/pdffiles/r40_501.pdf. [Accessed: 16 February, 2016].

- ATP 3-75 – Ranger Operations. 29 June 2015. http://www.apd.army.mil/ProductMaps/TRADOC/ATP.aspx.

- Barber, B.E. (2004) No Excuse Leadership: Lessons from the U.S. Army’s Elite Rangers. 1st Ed. London: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bryant, R. (2003) To Be A U.S. Army Ranger. St Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company.

- Creatwal, C. (2012) How to Pass your Patrol and Other Tips for Earning the Black and Gold. USA: Creatwal Publishing.

- FM 21-18 – Foot Marches. 01 June 1990. http://www.apd.army.mil/ProductMaps/TRADOC/FM.aspx.

- FM 3-21.8 – The Infantry Rifle Platoon and Squad. 28 March 2007. http://www.apd.army.mil/ProductMaps/TRADOC/FM.aspx.

- FM 3-97.6 – Mountain Operations. 28 November 2000. http://www.apd.army.mil/ProductMaps/TRADOC/FM.aspx.

- FM 3-99 – Airborne and Air Assault Operations. 06 March 2015. http://www.apd.army.mil/ProductMaps/TRADOC/FM.aspx.

- Hall, R. (2007) The Ranger Book: A History 1634-2006. North Charleston, North Carolina: Booksurge Publishing.

- Hall, R. (2009) Mountain Ranger: An Oral History of the US Army Mountain Ranger Camp 1958-2008. North Charleston, North Carolina: Booksurge Publishing.

- Kearnes, M. (2015) Healthy Habits For Prospective Ranger School Students. Infantry: Magazine of the US Army’s Infantry. July-September 2015, pp.40-43. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2015/Jul-Sept/index.html. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

- Liptak, E. (2009) Elite 173: Office of Strategic Services 1942-45: The World War II Origins of the CIA. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

- McNab, C. (2013) America’s Elite: US Special Forces from the American Revolution to the Present Day. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

- Neville, L. & Dennis, P. (2016) US Army Rangers 1989-2015: Panama to Afghanistan. London: Osprey Publishing.

- Posey, E.L. (2011) The US Army’s First, Last, And Only All-Black Rangers. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie, Reprint Edition.

- Ross, T.D. (2004) U.S. Army Rangers and Special Forces of World War II. PLACE: Schiffer Publishing Ltd.

- Rottman, G.L. & Volstad, R. (1987) US Army Rangers and LRRP Units 1942-1987. London: Osprey Publishing.

- SH 21-76: Ranger Handbook (2011-02).

- TC 3-25.26: Map Reading and Land Navigation. 15 November 2013. http://www.apd.army.mil/ProductMaps/TRADOC/AllDoctrineBySeries_Response.aspx?old_series=21.

- TRADOC Analysis Centre (2105) Ranger Assessment Study: Executive Report. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/wisr-studies/Army%20-%20Ranger%20Assessment%20Study%20Executive%20Report2.pdf. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

- U.S. Department of Defense (2013) U.S. Army Ranger Handbook: Revised and Updated Edition. Place: Skyhorse Publishing.US Army Ranger Regiment (2013) Ranger Athlete Warrior 4.0: The Complete Guide to Army Ranger Fitness. Fort Benning, Georgia: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- USSOCOM (US Special Operations Command) (2016) 2016 Fact Book United States Special Operations Command. MacDill Air Force Base, Florida: USSOCOM.

- Werner, B. (2006) Elite 45: First Special Service Force 1942-44. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

- White, S.S., Mueller-Hanson, R.A., Dorsey, D.W., Pulakos, E.D., Wisecarver, M.M., Deagle III, E.A. & Mendini, K.G. (2005) Developing Adaptive Proficiency in Special Forces Officers. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/army/rr1831.pdf. [Accessed: 18 February, 2016].

4.3 Useful Links

- Airborne and Ranger Training Brigade (ARTB):

- Basic Airborne Course: http://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/rtb/1-507th/airborne/

- US Army: http://www.army.mil/ranger/

- Infantry (Magazine of the US Army’s Infantry), July-September Issue: http://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2015/Jul-Sept/index.html

- US Army Ranger Association: http://www.ranger.org/

- US Army National Guard Warrior Training Centre (WTC): http://www.benning.army.mil/tenant/wtc/

- Marine Corps Detachment, Fort Benning: http://www.benning.army.mil/mcoe/usmc/ranger.html

4.4 References

Acton, M. (2015) The Guard’s Gift to Training. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.ngaus.org/newsroom/news/guard%E2%80%99s-gift-training. [Accessed: 25 February, 2015].

Alexander, D. (2015) Two Women Have Completed ‘The Army’s Toughest Training.’ Here’s What That Means For The Military. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/women-army-rangers_us_55d607fbe4b055a6dab33fc1. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

Bahmanyar, Mir (2011). Shadow Warriors: A History of the US Army Rangers. Osprey Publishing.

Callaghan, R. (2014) An Air Force First: ALO Graduates Ranger School. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.af.mil/News/ArticleDisplay/tabid/223/Article/526202/an-air-force-first-alo-graduates-ranger-school.aspx. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

Cary, A. (2013) 25th Infantry Division Activates Lightning Academy. Available from World Wide Web: https://www.dvidshub.net/news/printable/106177. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

Clausen, C. (2014) Airmen Lead The Way in Last Pre-Ranger Course. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.af.mil/News/ArticleDisplay/tabid/223/Article/535585/airmen-lead-the-way-in-last-pre-ranger-course.aspx. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

Correll, D.S. (2019) First female Air Force airman earns Army Ranger tab. Available from World Wide Web: https://www.airforcetimes.com/news/your-air-force/2019/09/03/airman-makes-history-becomes-first-female-airman-to-earn-army-ranger-tab/?utm_campaign=Socialflow+AIR&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com. [Accessed: 04 September, 2019].

Fang, M. (2015) First Women To Graduate From The Army’s Elite Ranger School. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/army-rangers-women_us_55d28cf6e4b055a6dab13d5f. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

Hammes, R. (2014) Academy Airman Completes Ranger Assessment Course. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.af.mil/News/ArticleDisplay/tabid/223/Article/555170/academy-airman-completes-ranger-assessment-course.aspx. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

Kearnes, M. (2015) Healthy Habits For Prospective Ranger School Students. Infantry: Magazine of the US Army’s Infantry. July-September 2015, pp.40-43. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2015/Jul-Sept/index.html. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

Keating, S. (2015) Was It Fixed? Army General Told Subordinates: ‘A Woman Will Graduate Ranger School,’ Sources Say. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.people.com/article/female-ranger-school-graduation-planned-advance. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

Macias, A. (2015) These 2 Badass Female Army Rangers Just Made History — Here’s The Grueling Training They Endured. Available from World Wide Web: http://uk.businessinsider.com/first-women-to-earn-army-ranger-tab-2015-8?r=US&IR=T. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

McCann, C. (2014) Airman Ranger Completes Grueling Army Training School. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.af.mil/News/ArticleDisplay/tabid/223/Article/473252/airman-ranger-completes-grueling-army-training-school.aspx. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

O’Toole, M. (2013) Women In Combat May Be Able To Train For Special Forces Roles. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/06/18/women-in-combat-special-ops_n_3461065.html. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

Pellerin, C. (2015) SecDef Opens all Military Occupations to Women. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.therecruiterjournal.com/secdef-opens-all-military-occupations-to-women.html. [Accessed: 04 December, 2015].

Sallette, W. (2012) 25th ID Ensures Ranger School Success. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.hawaiiarmyweekly.com/2012/02/02/25th-id-ensures-ranger-school-success/. [Accessed: 25 February, 2015].

Shaughnessy, L. (2011) Army Backtracks on Black Berets after more than a Decade of Debate. Available from World Wide Web: http://edition.cnn.com/2011/US/06/13/army.beret/. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

Tan, M. (2015a) Women To Start Ranger School Today. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.armytimes.com/story/military/careers/2015/04/20/women-start-ranger-school/25901823/. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

Tan, M. (2015b) Army Officially Opens Ranger School To Female Soldiers. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.armytimes.com/story/military/careers/army/2015/09/02/army-officially-opens-ranger-school-female-soldiers/71580180/. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

Tan, M. (2015c) 3rd Woman, and 1st Female Reservist, Dons Ranger Tab. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.armytimes.com/story/military/careers/army/2015/10/16/3rd-woman-and-1st-female-reservist-dons-ranger-tab/74070360/. [Accessed: 24 February, 2016].

Thomas, E. (2014) Women Invited To Apply To U.S. Army’s Elite, All-Male Ranger School. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/09/17/female-rangers-us-army_n_5832428.html. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

Vogel, J.L. (2015) Statement of General Joseph L. Vogel, U.S. Army Commander United States Special Operations Command before the House Armed Services Committee, Subcommittee on Emerging Threats and Capabilities, March 18, 2015. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.socom.mil/Documents/2015%20USSOCOM%20Posture%20Statement.pdf. [Accessed: 29 December, 2015].

Wiehe, N. (2015) Italian Ranger Trains to Become US Ranger Instructor. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.defense-house.com/defense-news/italian-ranger-trains-to-become-us-ranger-instructor/. [Accessed: 25 February, 2016].

Yuhas, A. (2015) First Female US Army Rangers ‘Open Up New Doors For Women’. Available from World Wide Web: http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2015/aug/20/first-female-us-army-rangers. [Accessed: 23 February, 2016].

You must be logged in to post a comment.