Editor’s note: This is the third and final part of Aspen Journalism’s series on the removal of the Ute people from western Colorado. Parts one and two detailed the Battle of Milk Creek and the subsequent killings at the White River Indian Agency of Indian Agent Nathan Meeker and his staff.

Chipeta, “the queen of the Utes” and wife of the peacemaker Ute Chief Ouray, eulogized her husband near the Los Pinos Indian Agency after his death by kidney failure on Aug. 24, 1880, near today’s Montrose. She capsulized the Utes’ subjugation as prospectors, settlers, speculators and railroads rushed into Colorado.

“The sorrowing widow of the dead Ouray speaks to you. … Chipeta comes to you to weep over the loss of our people and the greed of the paleface. … All about are the graves of our people. … The fair Colorado is now overrun by the silver-plated senator [Teller] and the soft-eyed dude. The refinement of the oppressor has come with its [Indian] schools and gin cocktails and flour and bread and fall elections, and we linger here like a boil on the neck of a fat man.”

Earlier, the Jan. 31, 1880, edition of the Leadville Weekly Democrat typified the statewide clamor of settler entitlement, writing, “The Indians will be driven from a state which they have desecrated with the blood of innocent whites. The Utes must go.”

Gov. Fredrick Walter Pitkin (who was in office 1879-83) campaigned on the slogan “The Utes Must Go,” maintaining that Indians off the reservation could be shot by citizens. He has since been refuted for his demonization of the Utes and his mining interests in Ute territory. As tensions rose, the collision between the Ute Indians and the rush of settlers into western Colorado during the early 1880s smoldered to a climax.

Tidy hegemony

With the White River Ute Investigation of the Battle of Milk Creek and the nearby Meeker incident completed in January 1880, wherein Milk Creek was called a fair fight and the killing of Indian agent Nathan Meeker and 10 others at the White River Indian Agency was deemed criminal, the Utes resisted turning over the accused, believing they would not get a fair trial in Colorado.

Much to the outrage of newspaper editorials and public sentiment, the U.S. government did not vigorously pursue individual charges, but instead punished all Northern Utes by appropriating their territory for settlers. Most of those freshly minted Coloradans, awash in unashamed 19th century racism, heaped blame for this leniency on Interior Secretary Carl Schurz and East Coast Indian sympathizers.

Better historical understanding now views the killing of whites at the Indian agency as a concurrent front of the Milk Creek battle, because the Utes thought the large body of U.S. troops that crossed the reservation boundary at Milk Creek had come to eliminate them.

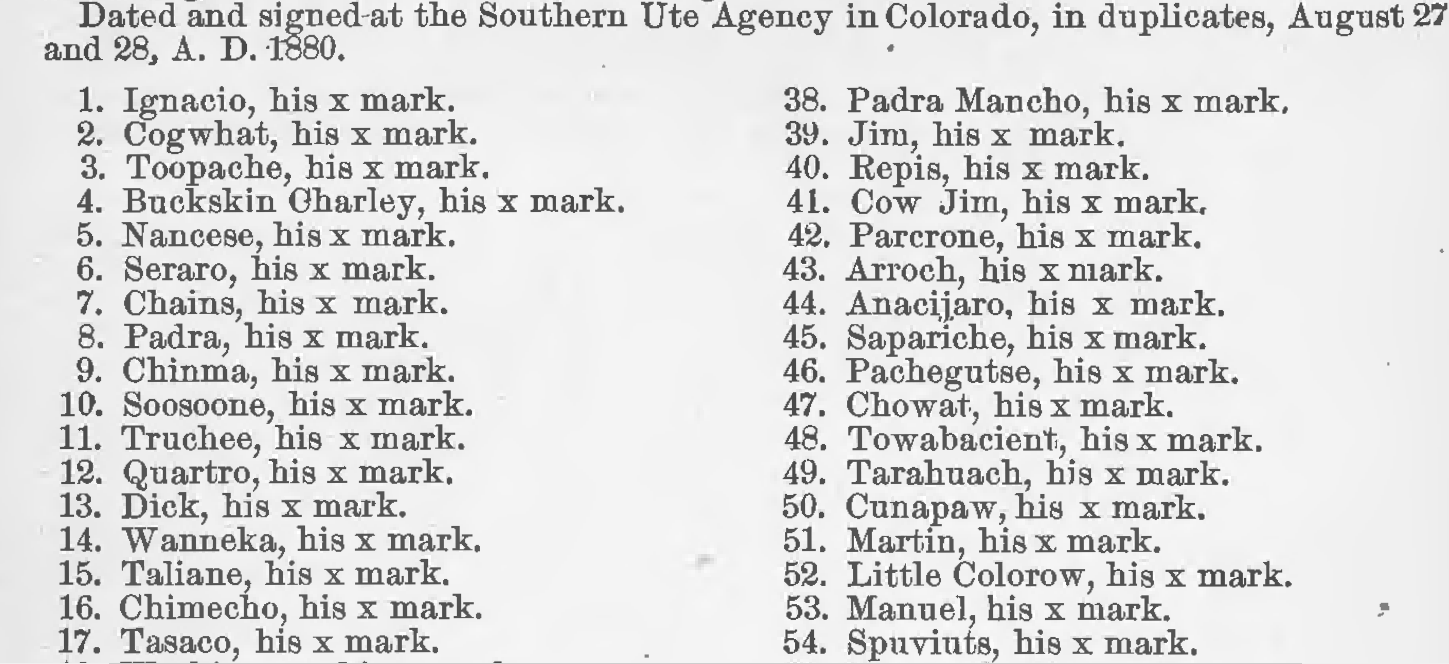

Shortly after the investigation concluded, the U.S. government brought Chief Ouray and Ute representatives to Washington, D.C., to ink a capitulation — not a treaty — on March 6, 1880, that hung a sword of Damocles over the remaining Northern Utes: The Uncompahgre Utes of the Uncompahgre Valley (near today’s Montrose) and the northwest White River Utes (near today’s Meeker) were directed to evacuate their territories and move to the Uintah and Ouray reservations in northeast Utah or face extinction; at the same time, the Southern Utes were confined to a reservation on a fraction of their original southwest Colorado territory.

Prior to that, an 1868 treaty had set aside most of western Colorado, from the 107th meridian (near today’s Aspen Village) to the Utah state line, as a reservation of the Utes.

This tidy hegemony opened western Colorado to the government’s vision of expanding civilization and utilizing the land for commerce, as opposed to the Utes’ low-impact use. Although outnumbered by garrisoned troops all around, the Uncompahgre (which means rocks that make water red) and the White River Utes negotiated and delayed for 18 months after the 1880 decree, forestalling removal to the reservations.

Because the White River and Yampa River valleys of northwest Colorado and Middle Park around today’s Granby were so vast, population pressures did not impose as quickly in the northwest region as the mushrooming settlements fueled by ore-value urgency and fertile valleys farther south down the Continental Divide.

Per 1873 and 1868 treaties, the Northwest Utes were allowed to hunt farther afield in their traditional northwest hunting grounds. But with the 1880 declaration, they were ordered to move to the Uintah and Ouray reservations and adapt to agriculture and government food allotments, while small hunting parties were tolerated off the reservation to trade.

Through this loophole, the resistant Chief Colorow of the Northern Utes — already in his 60s — and his remaining band of about 200 played cat and mouse with settlers in the northwest region, roaming and hunting as the last of the Colorado Utes living their traditional lifestyle. Chief Nicaagat (given the name “Jack” by white settlers) and his band reoccupied territory around the old Indian agency where Meeker died, until he moved north to Wyoming.

Inevitably, though, in September 1881 and in September 1887, showdowns led to Colorow’s expulsion. In 1887, a mixed force of sheriffs’ posses, cowboys and state militias that included volunteers from Glenwood Springs, Leadville and Aspen pursued Colorow’s band in a two-week campaign that newspapers dubbed the “Colorow War.”

Real estate flip

Six years before the final 1887 confrontation, in the aftermath of the 1880 agreement, U.S. troops garrisoned near the Los Pinos agency in the Uncompahgre Valley (near today’s Montrose) after the Milk Creek battle and the Meeker incident in 1879. The Uncompahgre Utes, native to the area, and some from the northwest White River Utes who had relocated there, were to be made examples of and compelled to relocate. In September 1881, that troop threat forced those Utes out of Colorado and into Utah to a site chosen by the Ute Commission — an arm of the Department of the Interior — charged with mapping out a new reservation south of the Uintah reservation, created in 1861 by President Abraham Lincoln.

In 1882, the new reservation became the Ouray Reservation. The two were combined in 1886 into the Ouray and Uintah Reservation. Brigham Young characterized the dry and barren area as not fit for a jackrabbit, a newspaper clip noted.

The May 7, 1881, edition of the Rocky Mountain News interviewed Otto Mears of the Ute Commission, wherein he estimated there were 1,400 Uncompahgre and 700 White River Utes in the state — with 1,250 Southern Utes already sequestered on their southwest Colorado reservation. However, payments to leave and the show of force only worked partially, because many Utes soon traveled back and forth into their old territories and clashed with settlers. Mears, a so-called friend of the Utes, acted as translator for the Ute Commission while his private interests were in laying out Colorado’s roads and railroad spurs in the former western Ute territories.

According to a Feb. 2, 1881, letter from Secretary Schurz included with the Ute Commission’s final report, which can be found in the University of Oklahoma Law School’s online archives, commission chair George W. Manypenny oversaw disbursement of $75,000 ($2.3 million today) to the Southern, Uncompahgre and White River Utes in compensation for the millions of acres of their surrendered domain. The Southern Utes received $25,000, the Uncompahgre $37,500 and the White River Utes $12,500. Coupled with farming plots on the Utah reservations, rations and annuities, these land payments were to reimburse them for moving to Utah.

Paymasters under military guard barred any gambling and scamming white men from the vicinity as they made these per-capita payments of several hundred dollars each in “silver and greenbacks,” first to the Southern Utes and then the Uncompahgre, the commission report said. Although the displacement of the Uncompahgre was the most urgent, with hordes of settlers and miners staking out plots before the Utes had even left, the more-dispersed White River Utes were told to collect their stipends at the Uintah Reservation.

The Ute Commission’s impatience with compliance, coupled with peaked tensions between settlers and Utes, led acting Interior Secretary Alonzo Bell in September 1881 to order Gen. Ranald Mackenzie at Fort Garland, Colo., in the San Luis Valley, to march 10 companies of cavalry and infantry north to the Uncompahgre territory.

At the same time, to the north, Gen. Wesley Merritt at Fort Steele near Rawlins, Wyo., commanded 1,200-1,500 troops, with a number of those still garrisoned near the former White River Indian Agency, where Meeker was killed. With reinforcements available from the northern torched-agency detachment and troops in place to the south, this pincer threat forced the more-gathered Uncompahgre to the new Utah reservation in September 1881, while failing to compel the scattered northern White River Utes to the Uintah.

The tragic September Uncompahgre evacuation described by a Capt. James Parker of the 4th Cavalry, found in Robert Emmitt’s comprehensive history of the northwest Colorado Utes, “The Last War Trail,” sketched the Utes’ 1881 capitulation as troops stood by. As chronicled by Parker, Mackenzie informed the chiefs: “If you have not moved by nine o’clock tomorrow morning, I will be at your camp and make you move.”

Parker added, “The next morning after sunrise we saw a thrilling and pitiful sight. The whole Ute Nation on horseback and foot was streaming by.” As they passed Parker’s troops, “their gait broke into a run. Sheep were abandoned, blankets and personal possessions strewn along the road, women and children were loudly wailing.”

With the Uncompahgre on their 225-mile journey to the Utah reservation, the military let loose the whites, “who hurried after us, taking up the land,” Parker wrote. “It was not desirable to let these civilians encounter the Indians. We were holding the crowd back on the south side of the Gunnison, until the Indians had passed 13 miles distant. In three days, the rich land of the Uncompahgre was all occupied, towns were being laid out and lots being sold at high prices.”

Many Utes return

Despite displacement, numerous Utes returned to Colorado within weeks of the resettlement. Some Uncompahgre Utes camped on the Utah border and traded with the settlers who had overrun their Uncompahgre homeland, but the porous and expansive northwest of the White River Utes drew many back to roam and hunt.

According to the Sept. 28, 1881, edition of the Gunnison Daily News-Democrat, “The White River Utes went to the Uintah reservation, but remained only long enough to obtain their money, and are returning to the White River.” The new civilian trading post proprietor in the White River area, J. B. Adams, gave an interview published in the Nov. 28, 1881, edition of the Rocky Mountain News that was titled “Loitering — The White River Utes still at their old home.”

Adams said that of the three remaining groups of Utes, the Southern remained on their reservation and only the Uncompahgre have been fully removed. “The White River Utes are hanging around the old agency, a vast majority of them. There is not sufficient grazing on Uintah reservation, not enough buckskin, and other reasons why the Uintah Utes don’t want them there.”

Maj. Bryant, who commanded five companies garrisoned by what would in 1885 become the town of Meeker, negotiated with Chief Nicaagat and his band, Adams recounted. Nicaagat said — written in degrading pidgin-Indian English, typical of the newspaper in the era — “White Rivers no chiefs; everyman a chief. Me no promise. … Colorado say Utes must go; Washington say nothing. Colorado big man; Washington small boy.” In other words, the Interior Department passed the buck to Gov. Pitkin to handle the remaining Utes.

As well as Nicaagat, Quinkent/Douglass and Colorow were also roaming their former territory with followers. Douglass, who had been inexplicitly released back to the White River Utes from Leavenworth by Schurz, was deemed “a lunatic” by the Utes, after acting hostile to his people and killing a young Ute woman. This led to the Utes’ killing Quinkent because of his bad spiritual lunacy.

As dynamics among bands off the reservation unfolded, Nicaagat with his small group became marginalized because of his earlier cooperation with Washington. In 1882, he was killed by soldiers’ cannon fire at the Shoshone reservation in Wyoming for being a “renegade” off the Uintah reservation. That left Colorow with his roaming band of about 200 Utes still in the northwest White River territory, often reinforced or visited by Utes from Uintah.

Last free-roaming Utes

As Colorow grew more emboldened between 1881 and 1886, he and his band traveled their old White River realm between Douglas Creek near the Utah border, up through Middle Park and the headwaters of the Colorado River, and as far south as Glenwood Springs. Although his heritage to the land was his justification, he claimed his signature had been forged on the 1880 expulsion agreement signed by Ouray in Washington.

Newspaper accounts routinely vilified Colorow’s band for setting fire to rangeland, stealing horses, slaughtering too much game for hides, drinking whiskey, harassing white settlers and unsubstantiated killings. Yet, numerous white merchants profited from having the Utes in the territory, acquiring pelts and skins, while selling them food staples, tools, beads, accessories for their ponies, ammunition and whiskey.

Many newspaper accounts burnished Colorow’s reputation as a rascal, retelling how as a younger, 6-foot-2 man, he once strutted through railroad cars on a Denver & Rio Grande line in his trademark plug hat, wearing only a leather loincloth, shocking white women. In another news clip, he was “disagreeable with a group of ladies out berrying.” He was also said to confront whites for food and tobacco.

As U.S. government troop deployment and fully manned forts throughout the West began to pull back from extended garrisons after most of the Native American population had been pushed onto reservations, settlers fended more for themselves. This became the case in the White River district after the bulk of troops in Meeker withdrew to Arizona, the July 21, 1883, edition of Leadville’s Carbonate Chronicle reported. After that, a standoff existed between the threat of Colorow’s ability to draw reinforcements from the Uintah reservation and the hesitant strength of posses and cowboys in the White River area.

The Rocky Mountain Sun on Aug. 1, 1885, wrote that Colorow camped at the hot springs in bustling Glenwood Springs, where his people bathed in the healing hot springs of “Manitou,” the great spirit, in between horse racing and betting with the whites. The newspaper wrote that Colorow’s band was slaughtering excessive game for hides to trade and leaving carcasses in Middle Park, while killing settlers’ cows and using the brains to tan hides.

Since Colorow was well armed and able to summon reinforcements by signal fires, ranchers and settlers avoided engaging. On Sept. 5, 1885, the Meeker Herald Times wrote that Colorow and part of his band visited town to gamble monte at a saloon and bet horse racing with the whites, and that he was camped three miles away. The Nov. 19, 1885, edition of the Aspen Daily Times reported that Colorow had moved north by the Yampa River (known to Utes as “Bear River”) with 14 lodges and about 50 Utes and 500 ponies.

In hot pursuit

Precipitated by a retaliation killing, in August 1887, new Gov. Alva Adams — who ended public executions and labor performed by children younger than 14 — called up the Colorado National Guard militias and volunteers to confront the northwest “Ute problem.”

According to a Glenwood Spring Post-Independent history story on Aug. 7, 2013, with the headline “The Rise and Fall of Sheriff James Kendall,” the Garfield County sheriff set out with a posse to arrest Big Frank and Senalo of Colorow’s band, which is said to have killed two Mexican men in payback for another Mexican man killing Chief Augustino of the Bear Creek band in the western White River Valley. The lawless area had a reputation as a harbor for Mexicans marginalized by the whites, one news story tendered.

Kendall faced a tough reelection because of a reputation for a “dark addiction to gambling and saloons,” the 2013 story said. To win, he tapped into anti-Ute sentiment by going after Colorow and seeking to arrest the accused Utes. This triggered a general call-up of Colorado National Guard militias, cowboys and ruffians by Adams. Brimming with bravado, these factions rushed north to fight Colorow, including Aspen’s militia, Company F, and an enthusiastic mix of Aspen volunteers. This final Ute campaign lasted less than three weeks, with only a few confrontations.

Numerous dispatches from the front appearing in the Rocky Mountain Sun, the Aspen Daily Times and other state papers in August-September 1887, as well as a two-part lookback series in the Aspen Times Weekly on Sept. 11 and 18, 1947, tell the Colorow War saga. Troop numbers, events, casualties and chronology often differed between accounts.

That said, as Kendall’s posse chased the elusive Colorow, they encountered small bands in Coyote Basin north of Meeker, after one of Kendall’s deputies burned Chipeta’s camp, taking her livestock. She hid in the brush with her adopted young Ute orphans, before joining the growing confluence of the women and children of Colorow’s scattered bands streaming together back to the Utah reservation, while the Ute warriors outmaneuvered their pursuers.

Kendall found Colorow west of Meeker near Beaver Creek. The chief refused demands to hand over Big Frank and Senalo. A skirmish ensued with injuries to both sides and Kendall, who wore a signature long black-seal coat, retreated with his men to woods nearby. The next morning, Colorow had slipped away and Kendall returned to Meeker to reconnoiter.

Colorow then circled north of Meeker and sent messengers asking to negotiate with Meeker “Mayor Gregory” and “Trader Major,” his pelt buyer. Meeting at Colorow’s camp, the two whites estimated he had 200 warriors there, and told Colorow he had to surrender the accused Utes and return to the reservation. Furious, Colorow rebuffed that he would prepare for a big fight. Word spread that attacks were imminent and settlers flocked into town for protection. Adams ordered detachments of Colorado National Guard to block off Ute reinforcement routes from Utah.

Colorow War

On Aug. 16, 1887, after receiving an urgent telegram from Adjutant Gen. George West of the Colorado National Guard, Captain F. H. Gosline of the Guard’s Aspen militia, rang the bell at the downtown armory on Hyman Avenue (not the former city hall building, built in 1891), summoning members to headquarters. Ammunition, rifles and supplies were issued and the detachment of 44 men rode the train to Glenwood, where horses and wagons awaited them for the trip to Meeker.

At the same time, Kendall telegrammed Pitkin County Sheriff J.D. Hooper — a former mayor and contractor who built the Pitkin County Courthouse in 1890 — for more posse. Within 24 hours, Hooper deputized 50-70 volunteers (many along the way) and set out to reinforce Kendall, and the Aspen militia. Hooper’s ill-equipped posse had few tents and not enough blankets or raincoats, and endured rain and snow on their march north.

All of Aspen celebrated Gosline’s militiamen and Hooper’s volunteers as departing heroes. Town businesses donated dinners, cigars and blue-denim overalls. “Charlie Boyd of Theater Mystique donated his brass band to play them through the streets and off to war,” the Aspen Times said.

By Aug. 24, 1887, both Aspen contingents combined in Meeker and were assigned to protect the town. Many were restless, itching to go right to the front. A number complained that the idleness cost them loss of wages back in Aspen and left, while Meeker did its best to entertain them during their wait for action, with a band, dances, fishing and barbecued game.

The “Aspen boys” settled in, but the underlying tension of a rumored Ute attack led to what The Aspen Times inaptly called the “Haystack Massacre.” Loose horses in camp during the night caused a ruckus and somebody yelled, “Indians!” The raw Aspen volunteers bumbled about trying to get atop a large haystack for a defensive position, injuring a number who fell from the summit in a farce with no enemy in sight.

Meanwhile, Kendall deputized Lt. Frank Folsom, Sgt. Murphy and Pvt. Ed Foltz of Aspen’s militia as part of his reinforcements. Farther afield, in Wolf Creek, close to the Utah border, Prey and 30 men of the Colorado Guard from Leadville and Denver found Colorow, who asked for a truce to talk with the “big chief” Adams.

Prey agreed and sent couriers to telegraph the governor, without guarantee. At dawn the next day, though, Prey attacked Colorow’s unsuspecting camp. With limited injuries on both sides, Prey captured the Ute food stores and gave Colorow several days to retreat to Utah. Receiving word, Adams took a train to Glenwood to a grand reception and dinner with Champagne and grandiose speeches at the Glenwood Hotel, before heading to Meeker the next day to “Camp Adams.” But it was too late to meet with Colorow, already pushed farther west.

Action at Wolf Creek

After being outflanked earlier by Colorow, Kendall with a larger posse, including the three deputized Aspen militia men and about 30 Aspen volunteers in a second wave behind him, rushed to reengage Colorow near Wolf Creek. They caught his trail close to the Utah border, northwest of today’s Rangely.

On Aug. 25, 1887, with Prey’s militia nearby, Kendall sent a scouting party of eight militiamen led by Folsom of Aspen ahead to find the Utes. Earlier that day, Kendall’s deputy Jasper “Jack” Ward had been killed during sporadic engagements. A bullet went through Ward, piercing Aspenite Ed Fotz’s cheek, said the Sept. 10, 1887, edition of the Rocky Mountain Sun. A man from Denver known only as “Curley” died as well.

Folsom’s scouts spotted Utes on a ridge and pursued them into an ambush in a ravine. Gunfire erupted and “a Ute bullet hit Folsom in his bowels as his horse reared,” wrote “Mitch,” a combatant and correspondent for The Aspen Times Weekly, on Sept. 3, 1887. The bullet hit a button on Folsom’s jacket, pushing it through and out the other side. Tom Walker of Leadville crawled 60 feet under fire to bring him water. As Folsom lay dying, he requested to face the sun because he was cold and was reported to have said to Walker, “I’m hit good; I know it; don’t leave me here to be scalped.” Whites took “souvenirs” off Utes also.

Hooper’s volunteers were late to Folsom’s fight, as the Utes hurried toward the safety of the Utah border, with Kendall trailing. The Aspen Times Weekly reported that Kendall’s posse and the state militia mix at the front numbered 150 while the Ute warriors were 125. After Folsom’s encounter, Hooper’s group captured “300 horses and lots of gewgaws — beadwork, robes, pelts and the Indians were set afoot and their loss probably 20.”

In hot pursuit, the posse and militia competed for the glory of catching the last of the free-roaming northwest Utes, while unbeknown to them, 100 or more Ute warriors from the Utah reservation were heading to help Colorow. But a Ute messenger from Colorow reached Fort Duchesne, and upon direct presidential orders, reported the lookback series in the Aspen Times Weekly in September 1947, a detachment of U. S. buffalo soldiers stood between the Ute reinforcements and the advancing Colorado groups.

The U.S. troops backed down the Colorado state forces at the border, declaring federal jurisdiction in what was reported as the only engagement wherein U.S. troops protected Utes against other whites. By order of the Interior Department, 400 ponies and belongings were returned to the Utes. The Colorow War was over.

The Oct. 22, 1887, edition of the Meeker Herald Times transcribed an earlier speech by Colorow to his followers: “Warriors, our sun has set. … Once I could stand on high ground and one shout would fill the forest with warriors. … Whiskey and refinement have filled our land with sorrow. The white man crossed the dark waters in his large canoe, and filled the forests with churches and railroad accidents.”

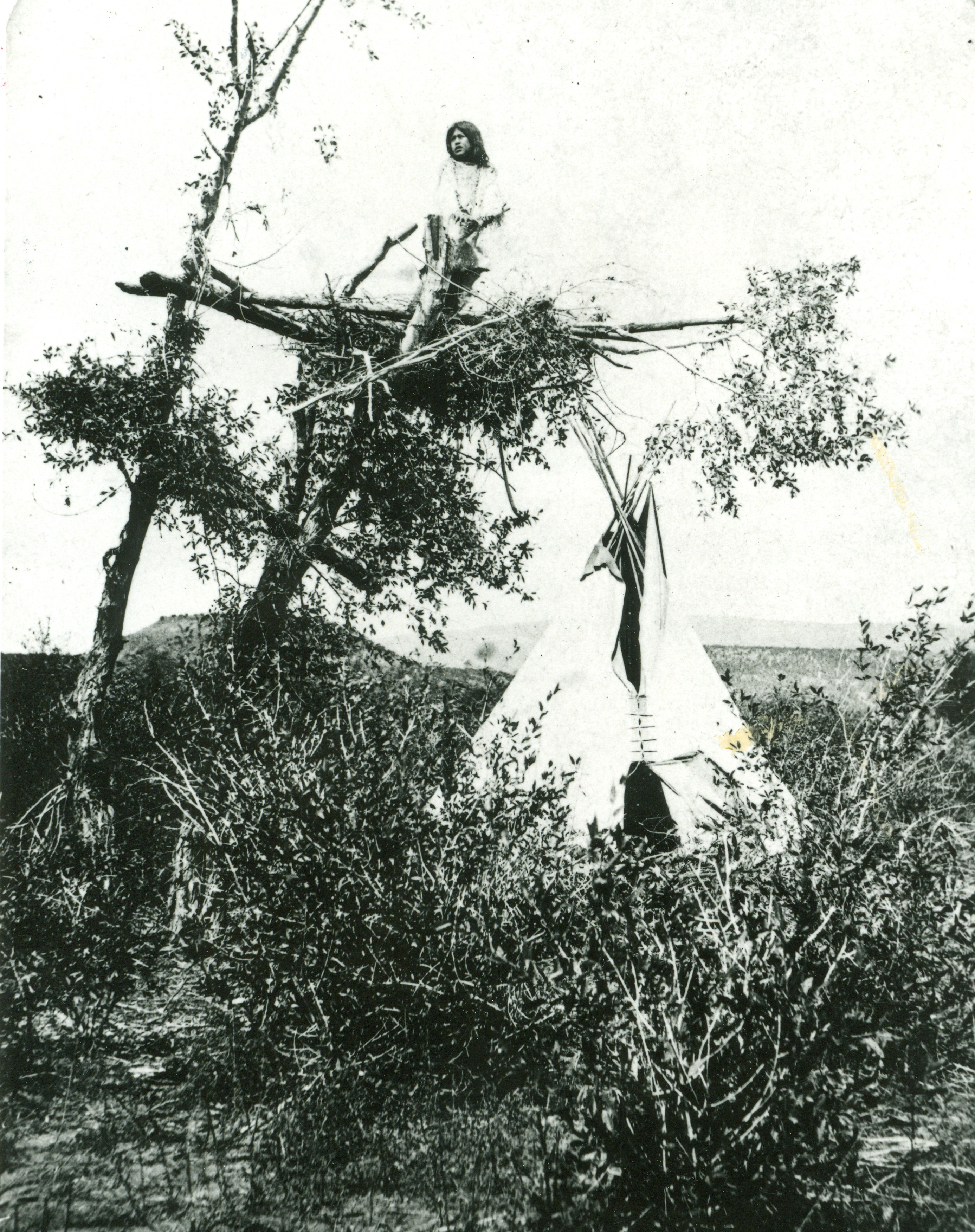

“Broken down with hardship” and in ill health, Colorow died a year later, on Dec. 11, 1888. His people carried him to the banks of the White River where it meets the Green River, south of the Uintah reservation. There, he died of pneumonia wrapped in his robes and blankets. Thirty of his favorite ponies were killed to be with him in his afterlife, said the Colorado Encyclopedia.

With nine children, many of Colorow’s descendants live on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation today.

Folsom and militia return

The Aspen militia marched back into Aspen from the “Ute War,” the Sept. 6, 1887, edition of the Aspen Daily Times reported. “The boys were well tanned and looked as if the trip had done them good,” the paper said. Crowds on every corner had gathered to greet them. Pvt. Ed Fultz’s “wound from the missile of death from a Ute rifle was regarded as a badge of honor.”

Amid cheering, they marched back to the Hyman Avenue armory, stacked their arms and paused where Folsom’s body lay in state under a flag-draped coffin. An honor guard stood by. Then, a hearse — with the whole town following — transported Folsom’s casket as “the air filled with the mournful strains of the dirge played by the band,” first to the Methodist church for his funeral and then to the Cooper Avenue bridge, where he was loaded onto a wagon for travel over Independence Pass to the Granite railroad station and burial in Des Moines, Iowa.

During the transfer, 16 men from Aspen’s Company F fired three volleys. Four militiamen accompanied Folsom’s remains over the pass to Granite. From there, along with Folsom’s wife and young daughter, 2nd Lt. W.W. Hills escorted the body to Iowa, the Sept. 7, 1887, edition of the Aspen Daily Times wrote. Folsom came from Iowa in 1885, explored the White River area, then came to Aspen, where he helped form the Aspen militia. His grieving mother lived in Aspen at the time of his death, according to his brief obituary in the Sept. 10, 1887, edition of the Aspen Times Weekly.

Garfield County Deputy Jack Ward, who died the same day as Folsom, at what the Aug. 28, 1887, edition of the Leadville Herald Democrat called the “Battle of Wolf Creek,” had been known as a tough fellow. Ward’s obituary in the Rocky Mountain Sun on Sept. 17, 1887, said he once backed off 12 men in Tin Cup, Colorado, in 1881, while forced against a wall with a pistol in each hand. Buried near Doc Holliday in the Glenwood Springs Pioneer Cemetery, Ward left a “stylish” wife and family.

The Leadville paper reported that eight Utes and two whites died in the final fight (not counting “Curley” of Denver), with 20 Utes and four whites wounded, two from the Leadville militia, while an “Aspen Scotsman killed two Indians and clubbed another to death.”

From pageant to powwow

The town of Meeker was, of course, named after Nathan Meeker, the Indian agent who accelerated the chain of tragedies as told in this three-part series about the last of the free-roaming Utes. Long after the displacement of Native Americans throughout the West, many towns with frontier history have begun to sort through the skeletons in their closets. Aspen in the 1880s, for example, banned the Chinese — then called “Celestials” — from town.

In the present day, over Fourth of July weekends, Meeker holds The Range Call Celebration, with a big rodeo, bands, vendors and multiple Americana events, as well tours of the Milk Creek battle site and a reenactment at the fairground of the incident at the Indian agency. Through 2011, the event was called the Meeker Massacre Pageant, but the name was changed in 2012 to the Meeker Pageant, the Meeker Herald Times reported. Now, the Meeker Pageant reenactment is a part of the five-day Range Call Celebration.

Of this name transition, the Aug. 12, 2011, edition of the Herald Times wrote, “The term ‘massacre’ is considered inflammatory, sensational, inaccurate and thus inappropriate by renowned Western history and Native American scholars and authors when associated with the facts of the 1879 conflict.”

The same paper explained on July 3, 2015, “The pageant is a reenactment of the last Ute Indian uprising, including the ‘Thornburgh Battle,’ and, of course, the ‘Meeker Massacre.’ However, it gives a neutral opinion of both sides and potentially provides perspective for those who have never heard the story.” The reenactment is portrayed by townspeople, and the Utes so far have not attended.

However, in 2008, descendants of the White River Utes returned in late July at the invitation of the Rio Blanco County Historical Society, Meeker Chamber of Commerce, U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management for the first Smoking River Powwow. Considered a start for reconciliation, an estimated 600 people attended, including Utes whose descendants were forced out in 1881.

The July 31, 2008, edition of the Herald Times quoted Loya Arrum, a Ute at the powwow, as saying: “Coming to Meeker had been a fearful thing.” Marshall Colorow, whose great-grandfather was the last free-roaming Ute chief, said, “I’m just happy to be here … for all of the things that happened … to come and see where my great-grandfather made footprints. I’ve been wanting to come here, but I didn’t know where to go.”

The same article quoted Joe Sullivan, a local historian and member of the Rio Blanco County Historical Society: “We’re trying to do a better job of portraying both sides. History is so important. If we can understand history, maybe we can avoid the mistakes of the past in the future.”

Nonetheless, history may not be fair. Thus, the state of Colorado was forged through the relinquishment and sacrifice of the Ute Nation, the People of the Shining Mountains.

This is the final installment of a three-part series covering the history of the Northern Utes’ removal from western Colorado. Click on the links to read parts one and two.

Aspen Journalism is a nonprofit, investigative organization covering history in collaboration with Aspen Daily News. This story was published in the July 9 edition of Aspen Daily News. For more, visit http://aspenjournalism.org