Many know the Ruedi Reservoir on the Fryingpan River 14 miles above Basalt as a fun place to camp, fish, water ski or sail. But few people realize that the water storage there flooded the onetime little town of Ruedi.

Long before the multifaceted Fryingpan-Arkansas water diversion project flooded the hamlet and spurred the construction of Ruedi Reservoir in the 1960s, small logging, mining and ranching settlements populated the Fryingpan River Valley in the 1880s.

The namesake of the underwater town, and the reservoir, is John Ruedi, a feisty Swiss bachelor who homesteaded what became known as Ruedi and “established the first post office in 1887,” according to the Sept. 25, 1941, edition of The Aspen Times.

Ruedi’s ranch bordered the Midland Railway route, which first brought trains in 1887 up to Leadville from Denver, over Hagerman Pass, down the Fryingpan River Valley to Basalt, and then up to Aspen. Before homesteading there, Ruedi lived in Aspen, had mining interests in Ashcroft and made the papers numerous times.

In 1892, the Glenwood Avalanche-Echo wrote that Ruedi had “120 head of young cattle and 20 of ponies.” He also built fish ponds and sold trout to the Midland Railway chefs. In a separate fish deal gone bad with the Parker meat market in Aspen over fish quality and nonpayment, Ruedi took the market to court.

The March 7, 1885, edition of the Rocky Mountain Sun reported that he once assaulted a county commissioner over a disputed 40 acres and was fined $3 and court costs.

The Basalt Journal in April 22, 1899, reported a $7,000 cost for the first wagon road from Basalt to Ruedi, with Ruedi as the “road delegate.”

The Glenwood Avalanche-Echo on Aug. 9, 1900, reported that Ruedi had been attending to his ill, depressed brother, Dr. Albert Ruedi, in a Glenwood Springs hotel. During an interim, the doctor fired his “bedside .38 caliber” into his own chest, “the ball piercing the left side of his heart.”

Life in Ruedi could be stark, if not fateful on the edge of the frontier, as evidenced by another crime of passion that disturbed the valley.

“Cold Lead Flew Thick and Fast for a Few Moments But Without Fatal Results … A Woman in the Case,” the Rocky Mountain Sun read on July 3, 1897, preceded by the headline, “A RUEDI SHOOTING.”

A dispute involving a widow, her young stepson, her brother-in-law and a neighbor escalated into a gun fight, when Ruedi rancher Robert Bridenthal became impassioned after the widow of his late brother, John Bridenthal, moved in with a neighbor, woodcutter Frank Estes, along with her 9-year-old stepson. The woman and boy had been living with Bridenthal since his brother died.

Tensions boiled over and Bridenthal “armed himself with a Winchester and started after the boy.” After confronting Estes, “hot words passed between the two men” and Estes opened fire on Bridenthal, firing four shots. Bridenthal returned fire. One bullet lodged in Bridenthal’s thigh.

They exchanged “11 shots at close range,” and “Bridenthal came off second best,” the Sun concluded. Bridenthal then managed “to bound up his wound” and hop a freight train at the Ruedi train station bound for Aspen, where physicians removed the bullet from his thigh at the Citizens’ Hospital.

Ruedi sold his ranch along the Fryingpan River in 1906 to “Mr. Brown of Colorado Springs for $6,700,” according to that year’s Sept. 30 edition of The Aspen Times.

He then moved to Baggs, Wyo., a wild intersection of Indians, outlaws and horse thieves and where Butch Cassidy had a hideout. The Eagle County Blade noted on Jan. 10, 1907, that Ruedi died suddenly in Craig, Colorado, about 40 miles from Baggs.

Roots of diversion

Years later, Ruedi’s legacy would be flooded as part of the Fry-Ark Project, one of the most complex transmountain water-diversion plans in Colorado.

The diversion of water through tunnels from west of the Continental Divide to the east side in Colorado — which ultimately led to submerging the town of Ruedi — has roots in the 19th century when settlers needed more irrigation for arid-land farming along the state’s Front Range and Eastern Plains. By the 1930s, Arkansas River Valley farmers had tapped the headwaters of the Roaring Fork with the Independence Pass collection system feeding into Twin Lakes.

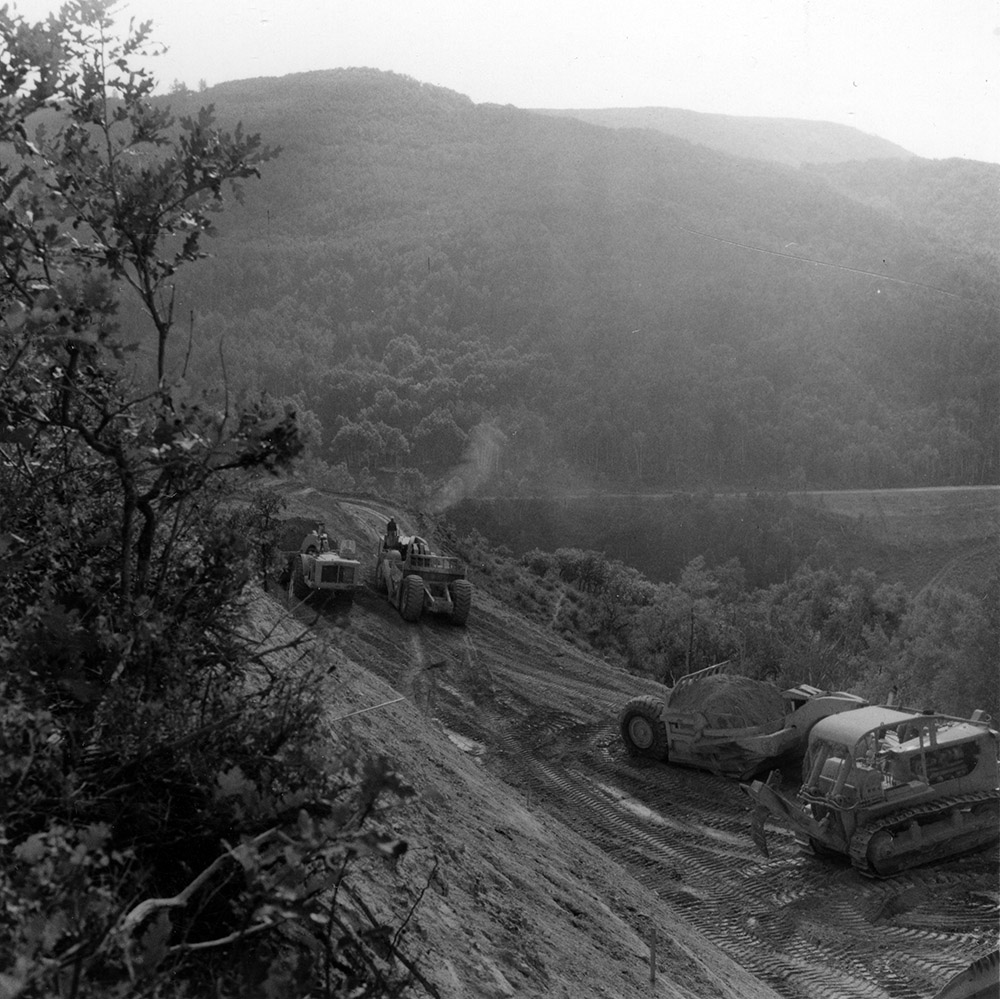

The Fry-Ark grew out of post-World War II optimism when government championed big projects and environmentalism was a seedling. The planning and debate for the water-redistribution system that now straddles both sides of the Divide played out between the 1950s and 1960s. The construction of its multiple parts took from 1964 to the early 1980s.

Industrial and agricultural interests centered in Pueblo, and Arkansas River Valley pressed their case for more water from the Western Slope in the early 1950s. In 1958, the Southeast Colorado Water Conservancy District was formed for the purpose of developing and administering the Fry-Ark Project, which it still does to the present.

Today the rearrangement of native water by the Fry-Ark Project from the Roaring Fork and Fryingpan rivers requires “six storage dams; 17 diversion dams and structures; hundreds of miles of combined canals, conduits, tunnels, and transmission lines; and two powerplants, switchyards, and substations,” according to Jedediah Rogers’ “The Fryingpan-Arkansas Project,” a 2006 Bureau of Reclamation document.

On the western side of the Divide, a half-moon-shaped, north-south collection system corrals percentages of water from both the upper Fryingpan and Roaring Fork river basins.

The Roaring Fork headwater is diverted from the Hunter Creek drainage above Aspen — tapping multiple creeks along the way — into a plumbing junction with the system’s northern arm, which reaches the North Fork of the Fryingpan River. From the intersection point near the Frying Pan Lakes trailhead, the water drains eastward through the 5.4-mile Boustead Tunnel under the Divide.

The Boustead Tunnel fills Turquoise Reservoir west of Leadville (east of the Divide). Water is then fed via an 11-mile conduit to another repository — the Mount Elbert Forebay — and into a hydroelectric power plant, where it is recirculated several times down and up via pumps to wring out more electricity. From there the water flows into Twin Lakes, into the Arkansas River and down to Pueblo Reservoir for municipal and agricultural distribution.

Turquoise Reservoir was expanded and Pueblo Reservoir was built during the multiyear Fry-Ark construction period, while Twin Lakes was enlarged in the 1930s, and again in the 1970s. Plans are on the drawing board to enlarge the 129,000 acre-foot Turquoise Reservoir by 19,000 acre-feet and the 357,000 acre-foot Pueblo Reservoir by 54,000 acre-feet, but Congress would need to authorize a feasibility study for the projects to proceed, according to the SCWCD website.

From 1982 to 2012, an average of 57,000 acre-feet of water each year passed east through the Boustead, but the system could take more.

According to the Fry-Ark’s operating principles established in 1950, up to 120,000 acre-feet may be diverted in one year with the right combination of snowpack, runoff and precipitation, but diversions must not exceed 2.35 million acre-feet over a rolling 34-year period, which comes to an annual average of 69,200 acre-feet.

Ruedi Reservoir itself does not play a direct role in physically diverting water from the Fryingpan River basin. Instead it stores water to be released down the Fryingpan to its confluence with the Roaring Fork River in Basalt, and then down to the Colorado River in Glenwood Springs. The Bureau of Reclamation-owned reservoir plays a critical role in how the basin manages its water supply, while water shareholders there include the Ute Water Conservancy District in Grand Junction, the Colorado River District, Exxon Mobil Corp., and the cities of Aspen, Glenwood Springs, Rifle, New Castle and Silt.

A carrot for the Western Slope?

Federal approval for the Fry-Ark Project languished in Congress for years, but Ruedi Reservoir, which can store 102,373 acre-feet of water, was the lynchpin to getting the deal done.

The prospect of Ruedi Reservoir assuaged Western Slope Democratic Congressmen Wayne Aspinall — a lion of western water-management between 1949 and 1973 and who straddled Western Slope water-retentionists and federally backed Eastern Slope water-opportunists — to sign on with the Fry-Ark Project.

Local raconteur and historian Tony Vagneur recollects there was “a lot of irate talk among western Coloradans during the 1960s (about) how Wayne Aspinall sold us down the river.”

Many western Coloradans resented losing “their” water, saying it should be left for Western Slope growth and industry — such as oil shale, coal and uranium — at a time when Colorado growth was the holy grail.

Aspinall also rebuked the budding environmentalist movement as “over-indulged zealots,” while he preached how the national value of the Fry-Ark Project wedded well with the compensatory carrot of Ruedi Reservoir, built to repay Western Slope users for their lost volume.

Meanwhile, in southeastern Colorado, Republican Congressman J. Edgar Chenowith, best known for bringing multiple defense projects to his district and the U.S. Air Force Academy to Colorado Springs, trumpeted the Arkansas River Valley’s need for more agricultural water coupled with the need to hydrate military installations.

In 1958, Aspinall and Chenowith consolidated factions to finally agree on Fry-Ark, heralding a statewide consensus. Yet the congressional sausage factory took another four years to pass the bill, which President Kennedy signed on August 16, 1962, in Pueblo.

Aspen Reservoir

Before Ruedi Reservoir made it onto a blueprint, the anticipated compensatory storage vehicle was the potential Aspen Reservoir.

Conceived as a payback for the skeletal flow of water between August and October in the Roaring Fork, caused by the 1930s-era Twin Lakes diversion through the Independence Pass tunnel, the reservoir would have stored 28,000 acre-feet for Roaring Fork and Western Slope replenishment, according to a story headlined “Dream Pending” in the June 13, 1954, edition of The Denver Post.

On July 21, 1949, The Aspen Times reported that a drilling rig from Denver had arrived in Aspen to core-sample ground for a dam site east of town, for what was then the shoot-for-the-moon antecedent of the Fry-Ark, the defunct Gunnison-Arkansas project.

First aiming to divert between 600,000 and 800,000 acre-feet from the Gunnison and Roaring Fork watersheds for the Arkansas River Valley, the Bureau of Reclamation and Congress backed off after monster opposition. They then floated the lesser, more palatable Fry-Ark idea, which would only take water from the Hunter Creek basin above Aspen and the headwaters of the Fryingpan, and not water from the Gunnison River basin.

Still, Western Slope opponents warned that if Fry-Ark flew, more diversion could follow. They cited Bureau of Reclamation speculation that targeted Castle, Maroon, Snowmass and Taylor creeks, as well as the Crystal River, for dams and diversions, which included punching a tunnel through the Divide near Salida to deliver that water into the Arkansas, according to a story in the June 7, 1951, edition of The Aspen Times.

At 650 acres, according to The Denver Post, Aspen Reservoir — about a third of Ruedi — would have inundated today’s Difficult Campground and the 175-acre North Star Nature Preserve, while lapping at the edges of a rerouted Highway 82. The $8 million dam was to be 88 feet high and stand at the western end of the nature preserve.

Aspen would have been an alternate reality with a recreational reservoir at the choke point of its eastern doorway, and no Ruedi Reservoir above Basalt. Instead of a mere paddleboarder plague on North Star waters now, Aspen could be dealing with a traffic-clogged marina and boat trailers stuck on Independence Pass.

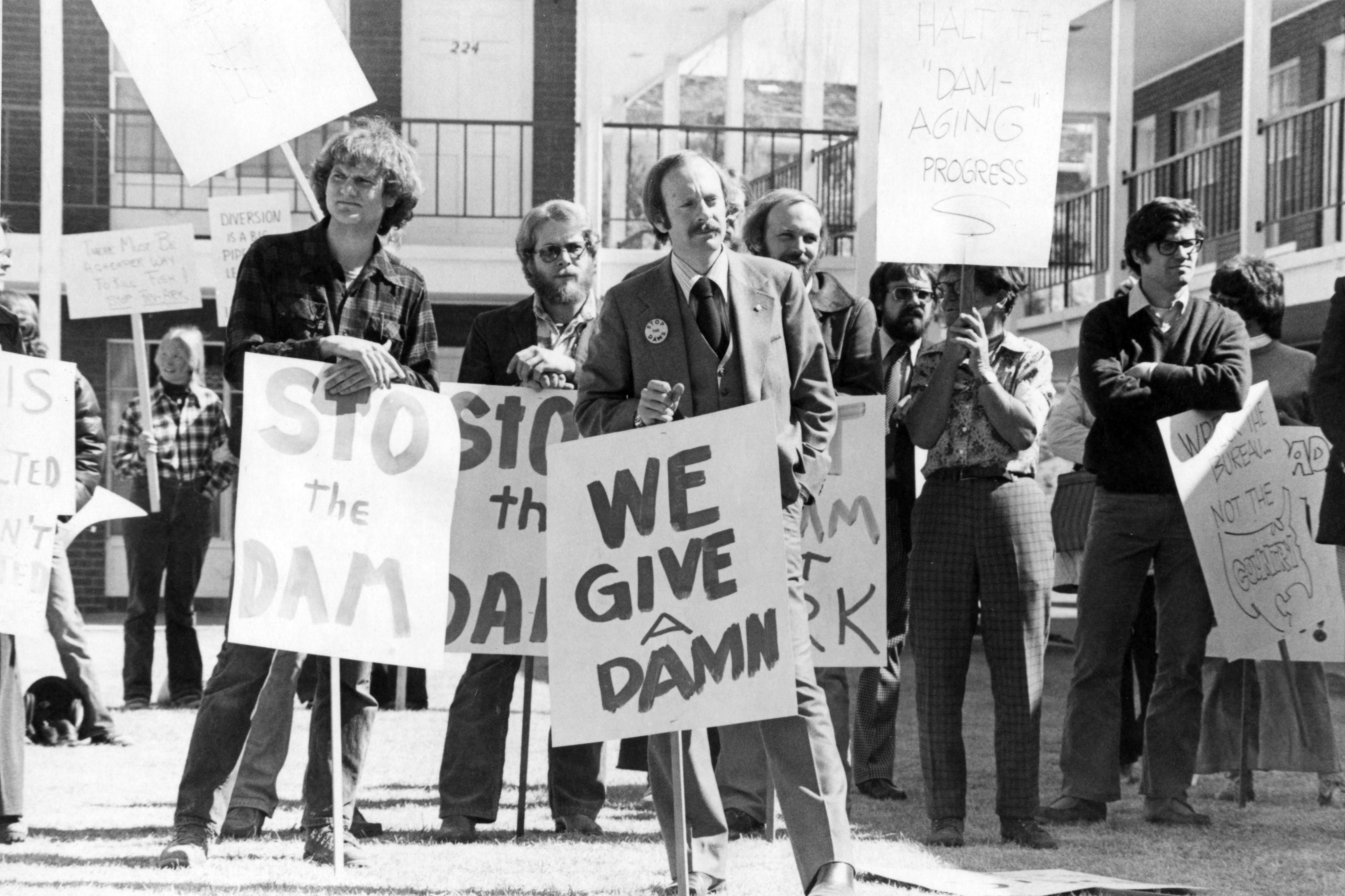

Fighting the diversionists

As Mark Twain observed, “There’s nothing to be learned by a second kick of a mule.” Having already been stung by the earlier Independence Pass diversion, the scrappy town of Aspen would have none of it.

In 1951, citizens formed the Pitkin County Water Protection Association to fight the Fry-Ark and “Aspen dam,” or “Aspen reservoir” as it was alternately known. Opinion pieces called the Colorado Arkansas Valley water interests “diversionists” and “Arkansasers.”

In a letter published in the Aug. 16, 1951, edition of The Aspen Times, Mayor Gene Robinson and County Commissioner Chairman Orest Gerbaz penned objections to the “Bureau of ‘Wrecklamation,’” calling the dam “menacing to the town of Aspen.”

They maintained that the potentially unstable construction to be built on a foundation of 200 feet of loose sand over “alluvial and rockslide sediment” would seep into countless mining tunnels and shafts below the dam site, and into town.

Yet Ted and Lillian Cooper, who ran the Rocky Mt Lodge near today’s Difficult Campground entrance, which would have been shoreside to the new lake, favored the reservoir. In a letter published in the Sept. 3, 1953, edition of The Aspen Times, they wrote how the lake would provide “recreation, fishing, and an asset to scenery” because “nature is often at her best when aided by the skillful ‘artificial hand’ of man.”

In a rebuttal days later, Delbert Gerbaz — a tireless Aspen advocate for western water rights, a historical train enthusiast and a one-time lift operator on Aspen Mountain — countered that “anyone with a sense of natural beauty considers the Grizzly Reservoir (570 acre-feet) on Lincoln Creek an eyesore” and “any accident of nature wouldn’t hurt the Coopers … their establishment is above the reservoir site.”

The June 7, 1951, edition of The Aspen Times recounted a turbulent meeting at the Pitkin County courthouse, where attorney Frank Delaney, representing the Colorado Water Conservation Board, explained that Colorado’s water allotment in the bedrock 1922 Colorado River Compact — an agreement among seven U.S. states in the greater basin of the Colorado River designed to head off future controversies — could be used anywhere in the state, which included the eastern side of the Divide.

Old and established water law allowed moving water from creek to creek, river to river and basin to basin. But that still didn’t sit well with some Aspenites.

Local opposition

On May 31, 1951, The Aspen Times characterized Fry-Ark as “a Water Grab.” Strong opposition persisted as versions of the Fry-Ark bill occupied statewide and national dialogue. Many argued that the U.S. already had a government-subsidized national surplus of agricultural products stored in warehouses.

The Denver Post on June 15, 1954, contrasted views that the price tag was a waste of taxpayers’ money versus how Fry-Ark “can make dreams come true for the long-suffering Arkansas Valley, a contributor to the nation’s food basket, a potential defense mineral arsenal, and industrial powerhouse.”

“The Fryingpan Arkansas Project: A Political, Economic and Environmental History,” a 2005 University of Montana thesis by Brian D. Peterson, cited wide-ranging opposition to Fry-Ark.

In 1957, the Western Slope County Commissioners Association, which included members from 24 western Colorado counties — a third of all Colorado counties — opposed the bill; and Rifle farmer Gordon Graham, representing a “farmers’ union,” pledged to Rep. Aspinall: “We will fight till hell freezes over for the water rights of the Western Slope.”

But Fry-Ark advocates pounded home that the shared benefits of agriculture and national defense outweighed Western Slope objections.

The apple-pie marketing of the final congressional bill, as outlined in Peterson’s thesis, says the Fry-Ark was approved for “irrigation, municipal, domestic and industrial use, hydroelectric power, controlling floods … recreation, conservation and development of fish and wildlife.”

And the sentiment that the native water’s flow west from the Divide ought not be reversed eastward to satisfy a larger population cluster — thereby creating a water deficit in western Colorado — came to zilch, vis-à-vis water law. So, Ruedi Reservoir, with its tourist dollars and partial water-deficit replacement formula, became a showcase for post-war innovation.

Rear-guard action

But before Ruedi Reservoir could be built, the little town of Ruedi had to perish. Numerous stories published between 1887 and the early 1940s in The Aspen Times, Eagle Valley Enterprise and Glenwood Avalanche-Echo frame a story of the forgotten town.

The Aug. 21, 1897, edition of The Aspen Times published a story with the headline “Monster Silver Tip King in Gulch near Ruedi,” in which it reported a grizzly bear in the canyon narrows “feeding on (service) berries that refuses to give up the path to bipeds.”

One hunter “shouldering his Winchester” came face to face with the bear and dropped his gun in retreat, recounting how the erect bear stood 14 feet and weighed a ton, with a “terrible snarl and paws extended.” Earlier, another grizzly had been shot and skinned thereabouts.

In the late 1930s to early 1940s, “Mrs. Ethyl Williams” wrote a “Frying Pan” column in The Aspen Times, which documents the original spelling of “Frying Pan River,” before usage became “Fryingpan.” Williams’ column detailed the comings and goings of Ruedi residents and visitors.

A column in the Feb. 16, 1939, edition of The Aspen Times noted “Mr. and Mrs. Trump were in Ruedi on Monday.” Turns out a man named Harold Trump had a home there.

That same column reported a “ski party” at the “Bowles ski course” (a hill by their house) and that “Loyd Hurtgen hurt his knee quite badly,” and “the Lumsden children have a pet deer named Rather, which follows them three miles to school and likes to eat pie when he can find one set out to cool.”

In other columns, Williams recounted school mistress Peg Meredith with six pupils; Jesse Williams working at the Sanders’ Diamond G Dude Ranch; Howard Dearhammer excavating for a new store in Ruedi; the Sloss brothers’ ice cutting business; the Ruedi Ladies Club meetings at the Vanderventer home to knit for the Red Cross; and electricity reaching town in 1941.

The town of Ruedi’s train-stop heydays waned after the Midland Railway quit running in 1918. Between the 1920s and 1950s, a small community held strong. Ranching in the valley continued until dam construction began in the spring of 1964.

The last holdouts were scattered residents. Chief among them were Mr. and Mrs. Fredric Mclaughlin, according to a story in the Nov. 8, 1962, edition of the Eagle Valley Enterprise. Both were former state representatives and owners of the 1,000-acre Mclaughlin Ranch — which incorporated the onetime Sanders’ Diamond G. With the slated Ruedi Reservoir, the southern part of their ranch would be underwater.

At a meeting in Washington, D.C., the Mclaughlins maintained that the U.S. Geological Survey judged the proposed dam site too porous and that the reservoir wouldn’t hold water because its beaver ponds, fed by Pond Creek, emptied into a sinkhole they dubbed “Glory Hole.”

And in a story headlined “Fry-Ark’s Ruedi Dam May Not Hold Water,” the Nov. 2, 1962, edition of The Aspen Times warned that excessive salt deposits would over-salinate the Fryingpan River and kill the fish.

In his “Devil’s Advocate” column earlier in The Aspen Times, “KNCB Moore” cited the USGS “Mallory Report,” by William Mallory and submitted to the Bureau of Reclamation, as substantiating those claims. The Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists agreed.

Converted Fry-Ark promoter Rep. Aspinall scoffed at the Mclaughlins as “the McFish interest in this,” while Rep. Chenoweth dismissed objections as “essentially rear-guard action,” the July 26, 1963, edition of The Aspen Times reported.

Earlier, the June 13, 1963, edition of the Eagle Valley Enterprise reported the dam site was still undecided. After Aspen Reservoir had been scrapped, the Bureau of Reclamation looked at damming the Eagle River below Camp Hale near Leadville, before settling on Ruedi. The newspaper said that because of gypsum and dolomite found in test drilling, the Ruedi dam might leak “excessively.”

Aspinall countered — in Washington, D.C., speak — that “there is no substantial question as to the water holding of the reservoir site,” the Eagle Valley Enterprise wrote three days later. The Bureau of Reclamation then checked a site a half-mile downstream nearer to Basalt but returned to the original, where Ruedi dam now stands at 285 feet above the streambed and 1,042 feet across.

The Nov. 29, 1963, edition of The Aspen Times chronicled head Fry-Ark engineer James Ogilvie telling an Aspen audience that W.A. Smith Construction Co. of Kansas City low-bid the $13 million dam and reservoir.

Concerned about an influx of workers and trailer courts springing up in unzoned Pitkin and Garfield counties — such as the El Jebel trailer court — the sparse crowd who showed up on the same day as President Kennedy’s assassination learned of the projected $1.4 million-per-year payroll to be spent in the valley between 1964 and 1972, with the employment of 150 men.

This included Jim Hayes, the late Aspen renaissance man, maker of archetype silver-Aspen-leaf belt buckles, and driver of a giant Euclid earth-moving scraper on the Ruedi Reservoir construction site.

Groundbreaking to celebration

The July 18, 1964, edition of the Eagle Valley Enterprise reported on the Ruedi Reservoir groundbreaking ceremony, planned for the next day, punctuated by a symbolic dynamite explosion. Interior Secretary Stuart Udall, U.S. Sens. Gordon Allcott and Peter Dominick, U.S. Reps. Aspinall and Chenowith, and Colorado Gov. John Love attended.

After a citizens bus tour of the future dam site, the ceremony kicked off at 1:30 p.m. with speeches, followed by the 101st Army Band and a barbecue hosted by the town of Basalt and the Masons and Eastern Stars of Carbondale.

As Ruedi neared completion, the $17.2 million “heart of the Fry-Ark” — the 5.4-mile Boustead Tunnel — proceeded. The tunnel, completed in 1972, now pours into Turquoise Reservoir, which spills overflow down the conduit stem to the Mount Elbert hydroelectric forebay, then flowing into Twin Lakes and on to Pueblo Reservoir.

Unlike the Independence Pass diversion tunnel to Twin Lakes, which was bored in the mid-1930s by hard-rock miners who handset dynamite, the Boustead Tunnel was the first in the United States that was machine-bored through solid granite, according to Rogers’ “The Fryingpan-Arkansas Project” report for the Bureau of Reclamation.

A new Wirth-Erkelenz boring machine from Germany — a rock-chewing colossus “30 feet long, 10 feet in diameter, and hydraulically powered by three 200-horsepower motors that drilled through rock with 33,500 psi” — gained that distinction.

Six years later, Interior Secretary Rogers Morton and Gov. Love arrived in a chopper from Denver for the east portal dedication in “a tree-studded glen,” according to the June 29, 1972, edition of the Golden Transcript.

The Golden newspaper tallied the Fry-Ark project’s cost to date then at $275 million, and the dignitaries watched the bounty from the Roaring Fork and Fryingpan river basins gush eastward.

This story ran in the Nov. 28 edition of the Aspen Daily News.