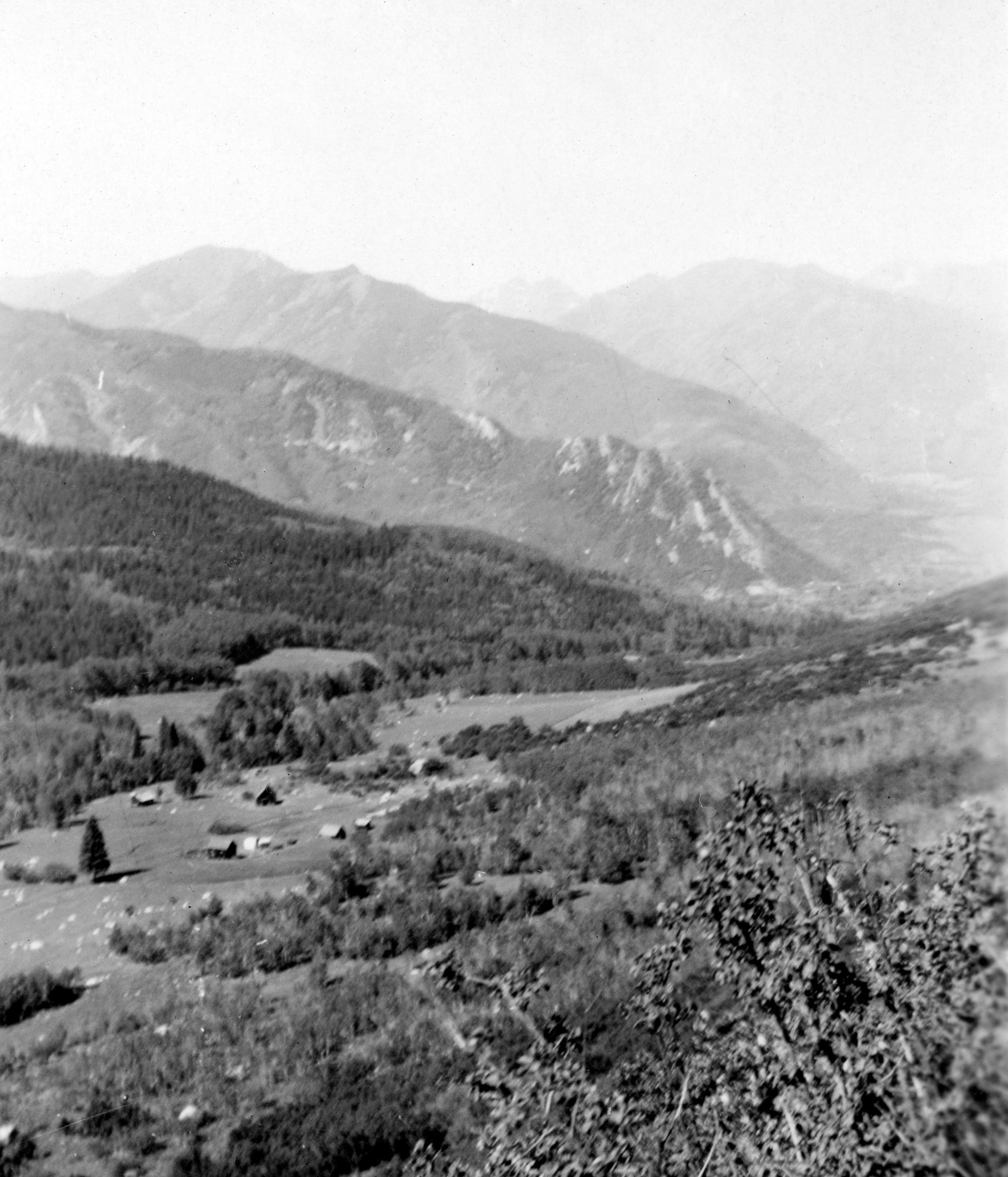

Aspen’s long-taken-for-granted backyard of Hunter Creek — once slated as an alternate road route to Leadville in the 1880s — attracted a group of five prospectors in late fall of 1879. Those “ ‘79ers” spent that first winter in the high valley of Hunter Park, holed up in their rough cabin with a five-gallon barrel of whisky and a big elk carcass for food, just as it started snowing on Nov. 5 and continued nonstop for four months. At the base of Aspen Mountain near the Ute Spring the remaining eight of Aspen’s “original 13” camped in crude shelters.

According to the Hunter group’s leader, Henry Staats, in his first-hand account retold in “Aspen on the Roaring Fork” by Frank L. Wentworth, the rumor of angry Ute Indians coming flushed the more skittish prospectors back to Leadville, but those first 13 chose to stay. The uptown splinter group in Hunter, who built their camp in October, coined Aspen’s original nickname, “Ute City,” for those clustered below.

Staats described a tall tree gage by their Hunter cabin that recorded 52 feet of fallen snow, which settled into a consistent six to seven feet on the ground through spring. Hunkered in, those that hastily built earth and wood bunkers in town burned pitch pine wood all winter. “Not a man among them could build a chimney that could draw,” he wrote, “so they had to take the smoke or live out of doors.” Whenever the downtowners emerged from their shelters between storms, their skin appeared pitch-darkened by the soot, to Staats’ mind resembling the Utes. Thus, the actual origin of “Ute City” was a racialized characterization of the white settlers’ skin tone that would be insensitive today.

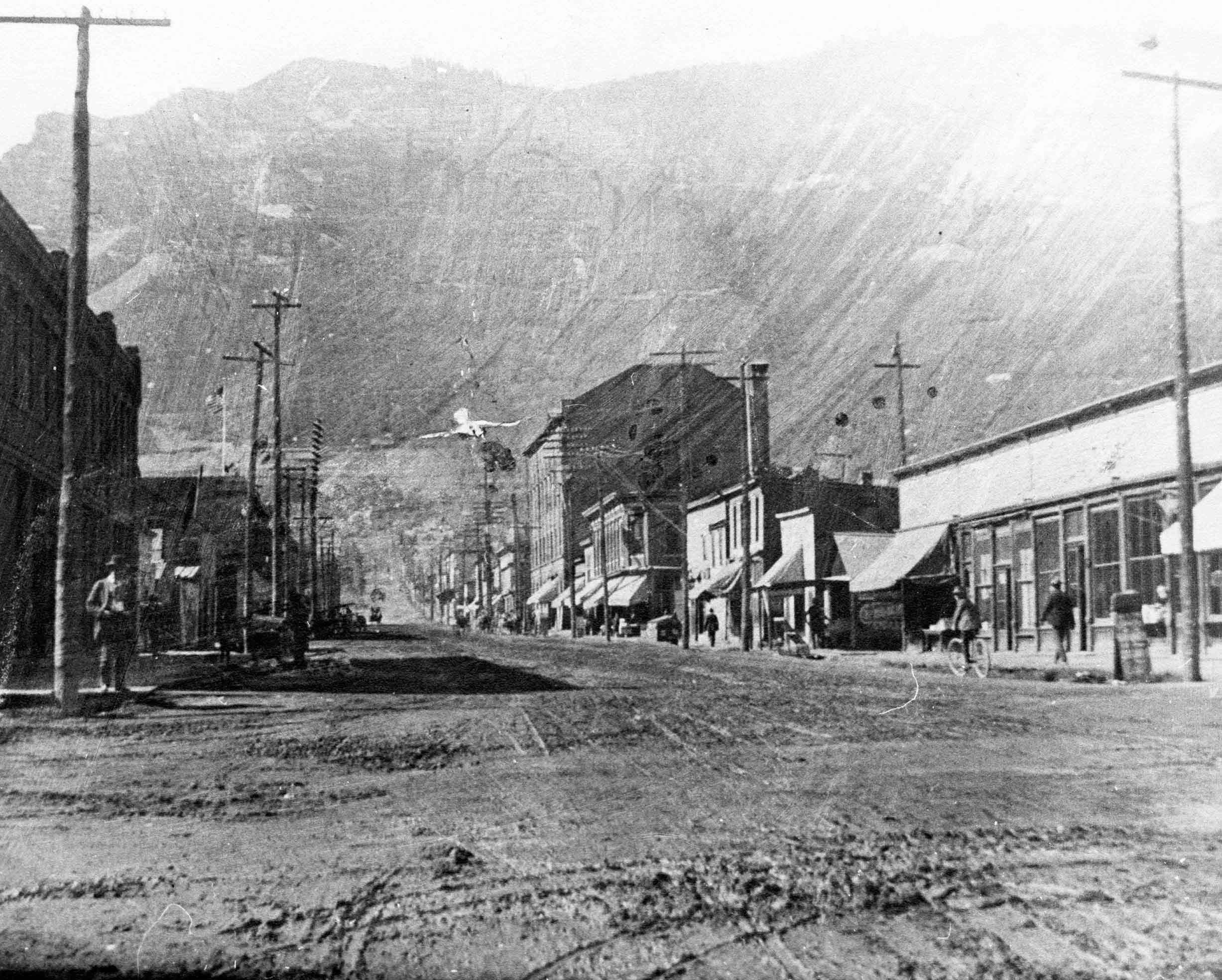

‘Baldy’ and ‘Old Needle’

Staats’ outfit consisted of J. Warren Elliot, “Old Bill” Blodget, Warner A. Root, and Mitchell Lorentz. While the partners worked on the cabin, Staats scouted for ore outcroppings and Blodget was said to “talk to and pet the whiskey keg so much we had to call him off it.”

After meeting Phil Praat who’d earlier laid out the Spar claim at the top of today’s Little Nell where the first silver ore outcroppings were discovered — the claim that set off the mining stampede into Aspen in the 1880s — Staats eyed straight across to Smuggler where the same lime and silver had surfaced. By his reckoning as a “high-line prospector” who studied ridges for outcroppings, rich claims should be found in Hunter Creek.

With grub supplies low and early snow, Staats recounts in Wentworth’s volume, Staats set off along Red Mountain from their Hunter camp on his sorrel horse “Baldy” with his trusty “Old Needle,” an octagonal-barrel Sharps 45-caliber rifle known in the West then as the “Old Reliable,” to find meat.

He spotted an enormous bull elk below on “Woody [Creek] Flats,” which he characterized as “the king of them all.” He “raised the rifle’s hind sight to 600 yards” and wounded the bull. A lengthy pursuit and four more shots finally brought the animal down. After multiple trips hauling the quarters, he and his associates tried to put the massive antlers a-straddle a pack horse, but the vast tines touched the ground. So they left them there on a stump, and “Billy Koch,” who built the first ranch up Hunter, appropriated them later.

Demimonde sparks shooting

Among the traffic jam negotiating Independence Pass into Aspen in early 1880 was William C. E. Koch, soon known as “the king of lumber,” who along with his brother Harry ran the Koch Lumber Company situated on today’s eponymous Aspen park at the base of Shadow Mountain. The Oct. 25, 1884, Rocky Mountain Sun printed the first ads for his business and The Aspen Times ran Koch Lumber ads in the 1920s to early 1940s, under different proprietors, until the company went into tax arrears.

Koch, who had prospered in town as a stable and saloon owner, mercantilist and Aspen’s first postmaster, homesteaded in Hunter while starting Koch Lumber. He sold hay, dairy milk, ice, and ran a sawmill farther up the creek, various snippets in the 1885 through 1896 Times and Sun recounted.

Though a pillar of the Aspen community, Koch became involved in a sordid scandal reported by the June 11, 1886, Aspen Times. The infamous Mollie Ross, an elegant demimonde of the Durant Avenue red-light district who wore a “plush silk cloak trimmed with fur and lined with the richest silk,” had been living with him at his Hunter Creek ranch. Abruptly she moved to town with real estate agent W. J. Miller.

“Shots rang out in downtown Aspen near the busy Clarendon Hotel,” drawing a crowd to the scene, said the Times. With a pistol in his back pocket, Koch confronted Ross at Miller’s house off Monarch Street. A front-door altercation resulted in Miller firing four shots at Koch with a 38-caliber. One grazed him and another passed through his mouth and out behind an ear. The next entered his back into his right lung, while another pierced his left ear, lodging in the back of his head. Death appeared imminent, and a deathbed-side lawyer transcribed Koch’s will, settling debts and leaving the bulk to his brother.

After the shooting, Miller ran up to Deane’s Addition near today’s 1-A ski lift, where a posse apprehended him. A bevy of town doctors extracted lead balls from Koch as he convalesced in his rival Miller’s bed. The June 30, 1886, Times said Billy Koch walked into the Times office, saying he felt vigorous, but for “feeling air pass through the bullet hole in his lung” where the slug remained. The Times opined him “worth a dozen graveyards.” Both well-off, Koch and Miller retained lawyers, but frontier law didn’t pursue the case after Koch refused to press charges.

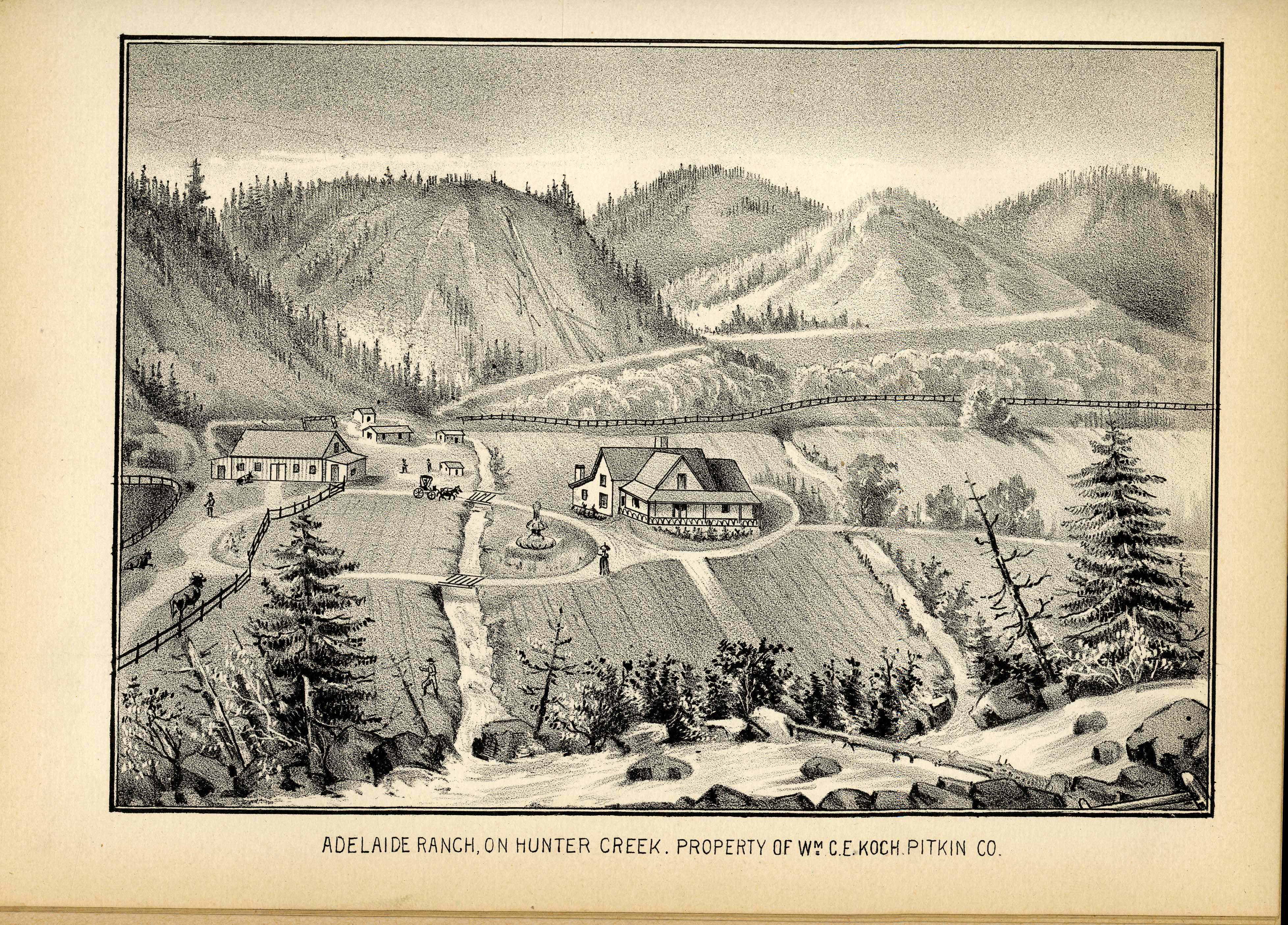

Koch had survived an earlier shot in his chest while employed with the Rio Grande Railroad in 1879, said the same Times. And the July 28, 1883, Sun reported him descending the steeps of Hunter Creek in his lumber wagon when the headyoke broke, spooking his team and tossing him underneath where a wheel ran over his shoulder. In 1890, the Times recounted him thrown from a horse carriage going up Hunter, becoming unconscious and tearing ligaments in his leg. Yet he found a wife, and the two suffered the death of their “idolized infant” at their “Adelaide Ranch” up Hunter Creek, the Jan. 13, 1889, Aspen Chronicle reported.

Several buildings of the Koch ranch still stand along the Hunter Creek trail, just below the old dam and reservoir site located in a marshy portion of the valley. An artist’s rendition of the Koch ranch in Hunter Creek at the Aspen Historical Society shows crops, cattle, and a fountain-like structure in front of a stately house along the creek.

Ross later claimed Koch had beat her earlier in a Glenwood hotel. “Competition for her favors were spirited” and Ross “had a lot of sway over susceptible hearts,” her brief Nov. 25, 1888, obituary read in the Chronicle. She died young in Kansas City.

Hunter hodgepodge

Deaf on one side from his gunshot wounds and with a slug left in his chest, Koch went on to start a lumber and mill operation up Hunter, briefly in partnership with another stalwart Aspen lumber man, Andy McFarlane, for whom McFarlane’s Gulch on the east side of Aspen Mountain is named. (See “Hope Delivers Pandora’s Box on Aspen Mountain”.)

McFarlane, who had been Aspen’s first sheriff in the early 1880s and a competitive town wrestler, brought the first water-turbine-powered “portable sawmill” to town in the summer of 1880 via Taylor Pass. His April 29, 1895, obituary in the Times said he set up the first mill in Hunter Creek, from where plentiful timber built most of Aspen’s first wooden houses.

The April 23, 1881, Times located the mill on Blodget’s and Staats’ original claims “four miles up Hunter,” likely in today’s “Slab Park,” northeast of Bald Knob where old sawmill slabs are still stacked, per a modern topo map. McFarlane also ran mills in Ashcroft and up Difficult Creek, before falling down a shaft in the Della mine to his death while not carrying a candle.

Koch and McFarlane had differences over Koch’s 1887 Hunter Creek toll road through the Koch Ranch, the May 22, 1886, Times said, with McFarlane claiming he’d built the original road with an option for a toll station — probably why they parted ways in the lumber business. The July 25, 1891, Times reported that in response to demand for access into the valley for mining, charcoal processing, timber, hay, ice, dairy and ranching, the county bought the toll road for $13,500 ($396,000 today) and opened it to the public.

The valley was quite popular for fishing and restaurant-supply hunting early on. The July 4, 1885, Sun reported that “Mssers Campbell’s and Leonard’s ‘Island Grove’” dance pavilion, bar and shooting range, ran horse-carriage “hacks” from downtown Aspen up to their “embowered in trees” location in Hunter Creek. All this as lumber and ore wagons and other commercial traffic rolled by.

Adding to the potpourri, reports of a grizzly bear “a mile past the last ranch” in Hunter set one William “Rocky Mountain Billy” Alban and his dogs on the hunt, the Aug. 6, 1895, Times reported. Billy wounded the bruin from “60 yards distant” and it “turned head over heels a dozen times and laid on its back for two minutes before running into the brush.” Townspeople were cautioned of a wounded “silvertip” thereabouts, but Billy returned to the carcass and brought the skin back to town as evidence.

Treacherous road

The newspapers between 1882 through the early 1900s recount tragedies and scores of wagon, timbering and mining accidents in Hunter Creek. The steep Hunter Creek road zigzagged up to the flats before it was called Red Mountain Road, beginning at Sanders Brewery just over today’s Mill Street bridge.

The Sept. 9, 1882, Sun reported Mr. J. W. Elliott and son were caught in an explosion while working their mining tunnel in Hunter. Elliott had set a charge inside, left, and came back in with his son 15 minutes later. A delayed explosion of the first somehow ignited a dynamite stick in Elliott’s hand. Dr. Teller — who the Dec. 10, 1881, Aspen Times said became the first county physician — amputated his arm and extracted shrapnel from the two. Both survived.

The July 27, 1889, Sun told of Hunter Creek rancher John Adair being thrown under the wheels of his loaded timber wagon while descending the risky road. Dr. Teller said the cause of death was a broken back and crushed head. Adair left behind a wife and four children who lived in the West End.

Lewis Palmer, 16, had just bought a 44 Bulldog revolver in town and was shooting chipmunks with it in Hunter, along with his 14-year-old friend, the July 12, 1890, Times wrote. The younger boy had stood back to watch as Palmer shot one, and while removing the spent shell Palmer shot himself in the forehead. His body was brought to his family in east Aspen (poorer section of town) and laid out with his hat over his face.

The Sept. 2, 1890 Chronicle wrote of teamster Hyrum Tuttle, an employee of Koch, who was thrown from his wagon on the steeps and was crushed by the wheels. Brought to the Koch ranch, a Dr. Ashbough surmised from the copious blood coming from his mouth that he wouldn’t survive.

In 1892, an epidemic of runaway Hunter Creek Milk Company wagons was reported by the Sun. One flipped while descending from Koch’s dairy farm, splashing milk everywhere, scattering 5-gallon cans, and injuring the driver.

Notorious tough woman Jennie Adair, who ran a sawmill in the Lakeside Addition just off the today’s Rio Grande Trail where Adair Park is, got into a fist fight with lumberman Dick Pierce who was hauling logs down the Hunter Creek Road. She threw brush and logs in front of his team, claiming the timber came from her Hunter property. A witness attested that she roundhoused him to the ground several times before he knocked her out in a “two rounder,” said the Aug. 16, 1905, Aspen Democrat. Judge Sanders fined Pierce $25.30 for striking a woman.

No evidence shows that John Adair and his four children were related to Jennie, while her Sept. 1, 1938, Times obit said she had no heirs and her sawmill and 556 acres in Hunter Creek were for sale.

Chicken Bill’s gold

To stoke mining investment up Hunter Creek, “Chicken Bill” Lovell paraded “a bottle of gold quartz on the streets” from his claims on Lovell Hill in Hunter, the Dec. 20, 1884, Times wrote. Lovell claimed the “assay showed $56,000 in gold and $600 in silver” — if calculated from the percentage in an ounce of ore. Two Aspen newsroom foremen caught the bug and invested in the deal, one from the Democrat and one from the Herald, to no result.

Yet Staats’ premise that the silver vein ran north into Hunter and Lenado proved true, but with less dramatic results than the Aspen “contact” that apexed near the top of today’s Silver Queen ski run on Aspen Mountain and again on Smuggler, where paying mines boomed between 1887 and the national financial meltdown of 1893.

A surfacing ore vein was the optimal claim because it showed evidence of an apex, a legal concept of right to what lay contiguously below (see “Portal into Time“). This dispute, where sideline miners moving in laterally were poaching apex claims while characterizing their strikes as independent impregnations, was germinating in Leadville mining, to be settled by the Denver U.S. District Court in 1886 for apex hero, Aspen’s David Hyman.

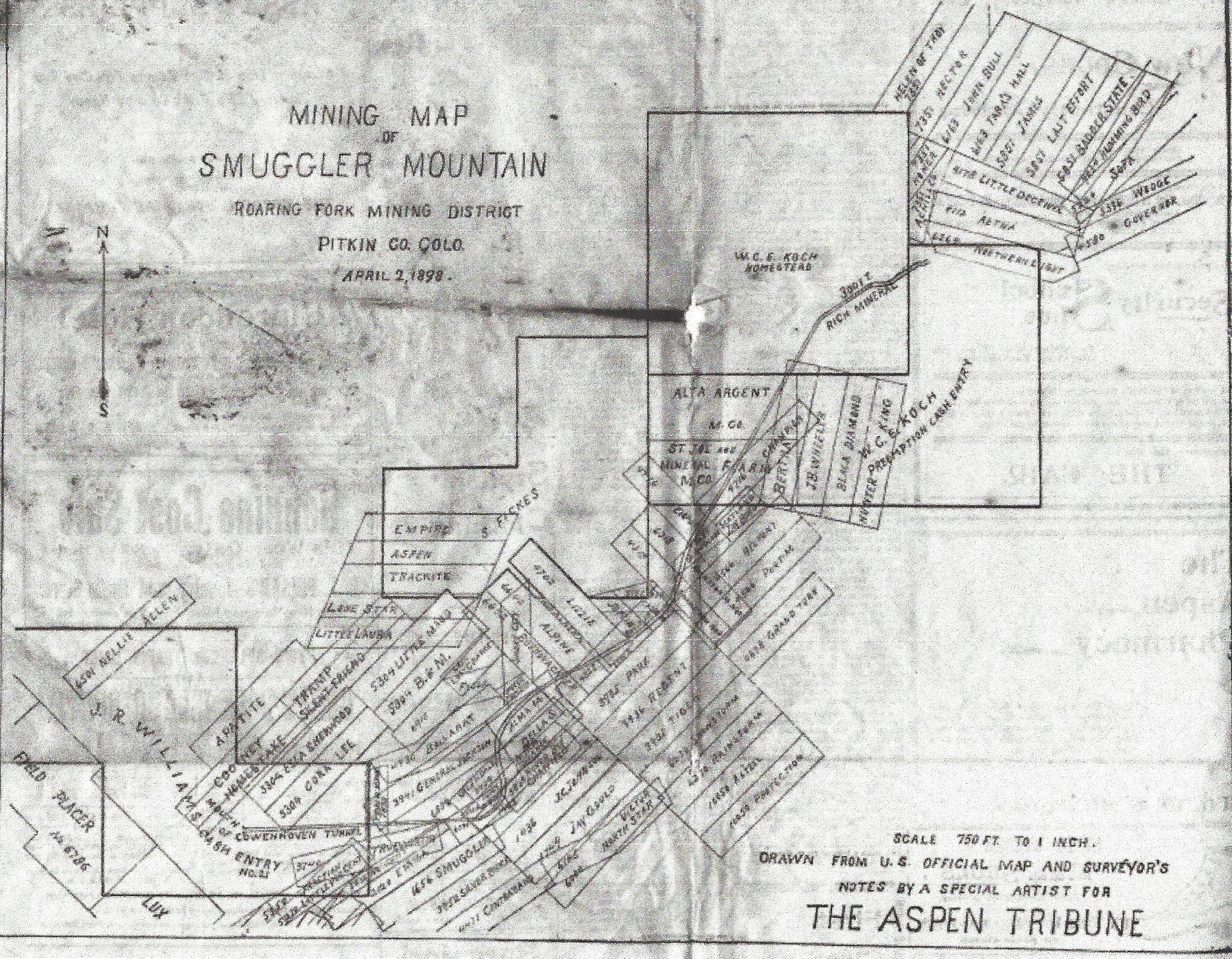

Staats thought he might find an apex in Hunter, but startups such as the Sofa, the Little Deceiver, Helen of Troy, Badger State, Last Effort and the Wandering Jew found lower grade ore. The Nov. 24, 1888, Sun reported the vein 700 feet underground and running north toward Lenado. Others found rich “float” — pieces of ore broken off and moved from their original location by natural forces such as frost or glacial action, indicating a source vein nearby.

Wheeler dealer

Conveniently, Koch’s ranch sat right on top of the Hunter Creek speculation, which would soon play out as prominent citizen and upscale scammer “Professor” B. Clark Wheeler, who named pristine “Aspen” in 1880 for the chattering aspen trees, partnered with Koch. They sold shares for a Hunter Creek tunnel to access ore from below claims abutting the ranch, the Aug. 8, 1888, Times recounted. They offered speculative stock and lower wages to workers, pitching a push of “150 to 175 feet per month.”

Koch and Professor Wheeler hoped to raise money and perhaps be bought out by D.R.C. Brown and his father-in-law H. P. Cowenhoven, who were building the Cowenhoven Tunnel along the same south-north Aspen contact. A map in the Aug. 8, 1888, Times illustrated the Hunter tunnel entrance near the Koch ranch, right where the Cowenhoven was aiming.

The Cowenhoven Tunnel, a crowning achievement of Aspen mining, was large enough for ore carts pulled by mules to travel in and out along two tracks below the lineup of Smuggler Mountain mines, starting in 1889. They contracted with the mines above to drain Smuggler water and transport ore to the railroad at its portal, where today’s Centennial affordable housing stands. “Mines and Mining Men of Colorado,” published in 1893, noted the tunnel had driven 1.5 miles under Smuggler Mountain and dealt with drainage of up to “1,500 gallons of water per minute.”

Tunnel merger

After coming up short on Hunter Creek mining, Staats took a lease in 1884 on the J. C. Johnson, the prominent mine dump just above today’s Smuggler mine operation. There he verified that the Aspen silver vein continued into Hunter territory, after he and 80 men squared out the mine in 11 months, according to his account in Wentworth. But just when they hit rich ore, his lease ran out and the owners wouldn’t renew.

Adjacent to the Johnson, the Della owners “Old Bill Pender and Jim Flemming sold to D.R.C. Brown for enough to get drunk a few times and buck taro for a week,” Staats wrote. Brown then sidelined only 75 feet into the Johnson to the vein Staats had hoped to pursue. Frustrated, Staats gave up mining, married and took up ranching downvalley, saying “his narrow escape from being rich made Dave Brown a millionaire.”

With that, Koch’s and Wheeler’s Hunter tunnel speculation paid out. The Della strike, along with the Mollie Gibson and Smuggler mines, the two major players on Smuggler Mountain (see “Dewatering the Smuggler Mountain mines”), inspired the Cowenhoven group to push on under Hunter toward Woody Creek.

According to the June 10 and 17, 1893, Times, Cowenhoven and Brown ponied up $25,000 for mineral rights under the Koch ranch right before buying the majority interest in the Koch homestead, rebranding it the Homestead Mining Company. The Times projected the tunnel merger would combine into a $5 million mining company ($147 million today) “to tap the bonanzas many hundreds of feet below the bed of Hunter Creek.”

But the “Crash of 1893” hit the national markets that summer, after overextended U.S. banks funded too many railroads, driven by western expansion and inflated commodity prices, including silver. With the fall of silver prices that autumn when the government quit subsidizing the metal for coinage, Aspen’s mining boom abruptly deflated.

Though Cowenhoven and Brown lost money and their tunnel momentum slowed, they remained well diversified in other enterprises. Koch retained a share in Homestead Mining, while Professor Wheeler walked away with a profit before the crash.

Miner Chris Preusch of the current Smuggler mining operation recounts how the Anaconda Mining Company in the 1940s drilled 5,000-foot holes in the Smuggler area for the U.S. war effort, looking for lead and uranium. Their exploration estimated some 850,000 tons of silver still lie deep below, corroborating Staats’ belief that a six-foot vein runs deep under Hunter.

Washerwomen’s day

By 1885, Aspen endured its first housing crisis. “Rents are high and domestics are scarce and command good prices…every type of business appears to be crowded,” the Jan. 3, 1885, Sun reported. Miners averaged $3.50 a day and paid about $10 per week for room and board.

Such growth and prosperity needed a bigger water system for the mushrooming town and to charge fire hydrants. With water for the city already coming from Castle Creek, the 900-foot torrent of Hunter Creek that dramatically cascaded into town presented the solution.

Concurrent with their Cowenhoven Tunnel work, Cowenhoven and Brown acquired city endorsement to pipe in Hunter Creek’s then-raging flow to their Aspen Water Company pipes throughout town, the Jan. 2, 1886, Times reported. With an elevation advantage over Castle Creek, Hunter water could push back Castle Creek water pressure in the town system, top off the Castle Creek reservoir — above today’s hospital — and supercharge water pressure to more fire hydrants about town.

By May of 1886, the wooden dam anchored in boulders several miles up Hunter and the reservoir there fed the town’s water pipes. That water journeyed from the dam down a flume built with wood from McFarlane’s Hunter mill to a wooden tank and into a pipeline under the Roaring Fork to connect with the water main on Mill Street. The May 22, 1886, Sun reported that McFarlane’s flume had a 9-million-gallon flow per day capacity, “sufficient to supply a city of 100,000.”

Many thought Hunter Creek’s lower mineral content was tastier than Castle Creek water. Dr. Teller, who was the first county physician, assessed Hunter water in the Feb. 21, 1886, Times, “with small quantities of sulfuric acid acting as a tonic…the magnesium as a stimulant to the kidneys…and lime able to produce gravel in the bladder.”

Town washerwomen preferred “soft as rainwater” Hunter Creek for laundry, while Sanders Brewery, which ran a ditch from the creek to brew its beer, characterized the “Adam’s ale” from Hunter as granite filtered and “pure as Kentucky water” in their ads.

Once Hunter Creek was hooked up, Mondays and Tuesdays became “wash days” when only Hunter water and not Castle Creek water flowed through town’s pipes. According to local historian Jim Markalunas, whose book “Aspen Memories” details valuable historical anecdotes over his life back to the 1930s, wash days continued on Mondays into the 1940s, until components of the Hunter Creek hydroelectric system all went to the U. S. war effort for scrap steel.

Hunter powers electricity

Well before the mid-1960s when the controversial Frying Pan-Arkansas water diversion project skimmed off the native strength of Hunter Creek to the Front Range (See “Town of Ruedi submerged by reservoir, but not by history”), the bountiful supply of Hunter Creek powered Aspen’s first electricity. A Sun snippet described the fall from the creek’s plateau into town as a “raging, deafening cataract” during runoff, often taking out bridges below.

By 1885, the first Aspen “Consumers Electric Light and Power Company” plant neared completion to tap that power at the base of the cascade, while the plant’s machinery was at the rail station in Granite, on the eastside of Independence Pass, the May 1, 1886, Sun said. Presumably, transport of the single 62-inch steel Pelton wheel (a wheel with circumferential cupped appurtenances pushed round by water flow) and two giant dynamos journeyed over the pass by wagon, since trains did not run into Aspen until 1887.

A few wrinkles remained. The April 1, 1888, Times reported that a cow had fallen into the upper Hunter Creek ditch and its carcass blocked the head-gate into the pipe that sent water to the power company, temporarily stopping electricity to town.

Soon that first Hunter Creek plant couldn’t power the multiplying mines and lighting in prosperous Aspen, and a larger one was built by 1889, which still stands as the former Aspen Art Museum on the Roaring Fork. That became the Roaring Fork Light & Power Company, which housed nine Pelton wheels pushed by 380 PSI of water pressure, or 500-plus horsepower, to expand service and provide “non-stop” electricity, the Jan. 1, 1889, Aspen Chronicle detailed.

Prior to the Pelton wheels, CEL&PC’s earlier iteration operated with wooden water wheels turning DC dynamos to a few electric lights. The first electric mining hoist in the world was at the Veterans Tunnel — located on today’s FIS Slalom Hill on Aspen Mountain — which the January Chronicle cited as starting on July 26, 1888. The Park-Regent, part of the contact lineup of mines across the way on Smuggler Mountain, ran a second electric hoist starting up on Oct. 1. Both ran 12 hours a day on Hunter Creek water.

Thus, in 1886, “The best little city in the Rockies,” as the papers often said, was independently positioned to have an endless water supply and its own hydro-powered electricity — the first west of the Mississippi — to propel its engine of commerce. Engineers from London and Japan journeyed to Aspen to study the innovative system.

Cowenhoven and Brown were members of the board in the evolving light and power company. Brown would go on to build Aspen’s third power plant under the Castle Creek bridge in 1893, which would operate until 1958, when Aspen lost its electrical generating independence and tapped the larger grid.

Hunter Creek legacy

After the Panic of 1893 and into the quiet years of the first half of the 20th century, when Aspen was still a backwater, timber and speculative mining ventures waned and ranching flourished. At the same time, a handful of working silver mines through the 1930s, content to meet demand at adjusted prices for lower grade ore, championed an elusive mining resurgence.

Reaching far back into the wilderness, the Hunter valley served as Aspen’s backyard for hunting, fishing and horseback riding, while ranching there still supplied dairy, hay and sheep herding space. During that halcyon era when the ratio of people and recreationists to wilderness didn’t challenge the vastness, nature not only tolerated a balance of land use in Hunter but reclaimed much of the land scarred by mining, sawmills and charcoal processing. The old Hunter Creek road provided free and easy access to all, when all were few.

The October 27, 1961, Times reported that Dub Tacker shot a bull and Orville Rusher a cow elk in Hunter, while Ken “KNCB” Moore faced a bear but “the bear’s retreat was faster than Moore’s attack.”

But beginning in the 1960s, pressure on the valley escalated as the Frying Pan-Arkansas water diversion project eyed Hunter Creek’s flows. And in 1962, a California development company in talks with the Aspen chamber of commerce bought the 1,850 acre Lemeque ranch in Hunter to build a “vacation resort there,” the August 31, 1962 Times wrote.

A 1963 booklet at the Aspen Historical Society titled “Development Plan of Aspen-Hunter Valley,” by Victor Gruen Associates, connected to a famed Austrian architect who pioneered shopping malls in the United States, details the speculative Hunter complex with up to 700 building lots, a village, lake, lodge and ski area. Strong local opposition against the plan popularized the derogatory term “California developers,” which became the incipient rallying cry for resistance against big development in town.

In the early 1970s conservationists and backcountry enthusiasts secured congressional approval of the federal purchase of the Hunter valley floor from McCulloch Oil Company, averting a planned 1,200-house subdivision. In 1978, Pitkin County transferred Hunter territory and mining claims it had purchased to the Forest Service, which the USFS rolled into the 82,450-acre Hunter-Frying Pan Wilderness area.

In 1987, the McCloskey family bought a 70-acre parcel from Fritz Benedict at the edge of the National Forest boundary at the entrance to Hunter Creek and built a monumental house. This became one of a string of emblematic Pitkin County struggles to curb wilderness trophy homes on mining claims.

In league with other Red Mountain homeowners, the McCloskeys blocked public entry on the county road by their property. A 16-year litigation ensued, wherein Aspen’s old and young guard formed the “Friends of Hunter Creek,” finally securing public access in 2004 to Hunter Creek via a compromise route, after the U.S. District Court ruled in 1998 that the north and south branches of the Hunter Creek road were public based upon the county purchase in 1891 of commercial access.

In October of 2004, Friends of Hunter Creek, the county and private home owners signed onto the mediated Hunter Creek settlement, which perpetuates public access to Aspen’s backyard playground in the scenic valley northeast of town.

Tim Cooney is a freelance writer and retired Aspen Mountain ski patroller. This story appeared in two parts in the May 30 and May 31 editions of the Aspen Daily News.